Aghalee mourns the loss of a grand old gentleman

The rambler26/12/2003

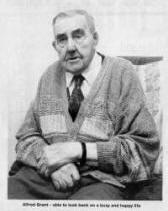

Mr. Alfred Grant

SUPREME raconteur; supreme basket-maker, supreme processor of mud turf; supreme

bowler - where could one stop?

SUPREME raconteur; supreme basket-maker, supreme processor of mud turf; supreme

bowler - where could one stop?A fine Christian gentleman who has lived out the greatest commandment and epitomised the immortal words of the balladeer.

If I can help somebody as I walk along, then my living shall not have been in vain.

With the occurrence of his 98th birthday (on 15th December), it is fitting to pay tribute to Aghalee's grand old man whose graphic soliloquy, quoted below, triggered off my decision made years ago to research and record local history for the benefit of posterity.

Alfred had only one standard in everything that he undertook the best and now that he has told his story and laid down his tools I will let his own words complete the picture.

Sadly this is vale as far as his rehearser of love is concerned.

Thank you Alfred. Well done.

THE HIRED BOY

I was just 14, and I had only left school. I hadn't any work, or a penny in my pocket. Times were hard in them days. My mother was having bother keeping me. This man asked me, one day, would I give him a day's work. I said I would, for I badly needed the money.

I asked him what I would have to do, and he told me he would show me when I went. "I'll tell you in the morning" was what he said. He had a wee bit of ground in the moss (Montiaghs) and when I went in the morning he said he had corn to harrow. He asked me to take one end of a wee harrow, with short pins.

I helped him down to the field with it. He had a rein-cord as well, and when we got to the corn-field he tied one end of the rope to the harrow, and gave me the other, which he told me to put over my shoulder. He showed me how to pull it, and where to go. On and off he gave me a hand. We were at it all day.

There was about an acre in the plot and we harrowed it all. I was tough at that time. I had had plenty of experience of hard work when I was at school - helping my father to make mud turf and draw them home, and milking, and driving the horse in the cart, and putting the harness on and off him, and things like that. At the end of the day - and it was a long one - he gave me one and six.

That would be seven and a half pence now.

When we had nearly finished, my father arrived with another man, a dairy farmer from the Tansy. He had heard I was strong and a good milker, and he had come to hire me.

He offered £18 and my keep, for six months' work. My father asked me would I go, and I said I would.

The man said he needed a good milker, and I was glad to hear it, for I was a dandy milker. I could have held my own with anyone - and maybe I still could.

I went to him on the Sunday night, that was 11th May, 1919. I started next morning - the 12th May. It was about twelve miles from home. I had an old bicycle that cost me thirty shillings, and I was paying sixpence a week off. When I got to the farm at the Tansy, the man was looking out for me. He called his wife out and said: "I want you to meet our new boy"

His wife was a very kindly woman. She made me tea, and gave me as much bread as I could eat. When I had finished, the man reached up above his head in the kitchen, and pulled down a ladder when he then set up.

Then he climbed up into the loft, and told me to follow him.

It was a lovely snug wee loft, with a nice single bed and things. There was a candlestick and a new candle, and a box of matches.

He asked me did I smoke and when I said I didn't, he said: "That's a good job. If you are lighting the candle be very careful, for you are close to the thatch, and you could put the whole place up in flames." I was very careful.

He said: "Your bedtime is half-nine and you will rise at half-five. I'll not call you twice."

He had 18 cows, and I had to have the milk at Ballinderry station for the twenty-past-eight train every morning. I took it in a keg, with the horse and cart. It would have been nearly two miles to the station.

Before I went to bed the first night I had to walk around. When I got to the back of the haggard, out of sight, I climbed a big ash tree to see if I could see home. I went right up to the topmost branch and I was swaying like a bird, but all I could see was Ram's Island and the Lough - no home.

I cried then, for I had never been away before and I was very lonely.

One day we had to dip the sheep. The man handed me an old shirt before he started and said:

"Give me your shirt and put that one on instead. We have to watch the tics." I did as I was told, and when we had finished, I had a good wash before I put my own shirt on again.

That night was the only time I lit that candle. I wakened up in the middle of the night with a terrible pain in my oxter. When I lit the candle I couldn't see what it was but I hoked with my thumb nail, and I brought out bits of an insect.

I couldn't get it all out, but I stopped the bad pain.

Next morning, the man and his wife looked under my arm and they said it was a tic. The woman dosed it with iodine, and I never looked behind me. Wasn't I lucky I didn't get poisoning?

I stayed for six months, but I was homesick the whole time. I used to get home for an hour of a Sunday.

We usually quit work about half-six in the evening, and I had nowhere to go, and I knew nobody. I never brought anybody in. I don't think them people would have liked me to have brought anybody about the house.

I got the best of food - beef every day nearly - but I never was able to eat much. I was that homesick. I just knocked about the fields, and haggard in the evenings, glad to give a hand with anything to pass the time. When I left, I never went back. Some people wondered at that for they had been very good to me.

Even when I got older and had a motorbike I never went. I just couldn't go back. I had been that homesick all the time.

After that, I got a job with a farmer at George's Island, but him and me had a dispute over pay. He was giving me fifteen shillings a week and he went to reduce it to twelve. I left.

My mother was upset. "What are you going to do?" she said. "Where will you get another job?" I said: "I don't care. I'm not going to work for that money", nor I didn't.

I got into a basket factory a wee while after that and I stayed for nearly twenty years.

• Shortly after this was written Mr Grant passed away. He was buried at Soldierstown graveyard on Sunday.

Ulster Star

26/12/2003