|

LONG

KESH

Ernie Cromie has provided a comprehensive and

interesting account of a part of our history.

When the United Kingdom declared war on Germany on 3

September 1939 there was only one military airfield in Northern Ireland.

By 1943 there were twenty-seven, four of which were located in what is

now Lisburn Borough, at Long Kesh, Maghaberry, Blaris and Sandy Bay on

Lough Neagh. Each of the four was used for a variety of purposes but

Long Kesh, Maghaberry and Blaris had a common origin which is of

particular interest in these days of professed Anglo-Irish accord!

In

drawing up plans for airfield development in Northern Ireland, the Air

Ministry planners were influenced by a number of considerations, one of

which was the possibility of a German invasion of the United Kingdom via

the 'back door', i.e. the Republic of Ireland. In that event, the

immediate British response would have been to counter-attack by sending

the army across the border with appropriate air support. Airfields were

therefore required in Northern Ireland to accommodate the RAF component

of this counter-invasion force and four were developed with that initial

purpose in mind. They were Sydenham, Long Kesh, Maghaberry and Blaris.

Two RAF light bomber squadrons, Nos. 88 and 226 were identified as the

Air Component and in June 1940 they arrived with Fairey Battle aircraft

at Sydenham. Being the pre-war civil airport as well as the site of a

rapidly expanding aircraft manufacturing industry, Sydenham was not the

ideal location. Due to shortage of space, and the airfield's

vulnerability to air attack (as demonstrated on 15 August 1940 when

Short & Harland's aircraft factory was bombed by the Luftwaffe and five

Stirling bombers were destroyed on the production line), there was an

urgent need for an emergency landing ground to which the 'planes could

be rapidly dispersed. This was obtained by the simple expedient of

taking over two large fields at Blaris, opposite the old graveyard,

which had been used occasionally in pre-war days for air displays or

private flying. Being a flat, firm, well-drained site with largely

unobstructed approaches, it was brought into use immediately as a grass

airstrip by the simple expedient of removing a few hedges and fences,

aircraft being dispersed in the open and personnel being accommodated in

tents. Records indicate that Fairey Battles and Anson aircraft from No

24 Elementary Flying Training School at Sydenham used Blaris in 1941,

and in due course the site came under the administrative control of Long

Kesh, being used for gliding instruction by the Air Training Corps from

1942 until the end of the war, under the direction of Wing Commander

Delap. In

drawing up plans for airfield development in Northern Ireland, the Air

Ministry planners were influenced by a number of considerations, one of

which was the possibility of a German invasion of the United Kingdom via

the 'back door', i.e. the Republic of Ireland. In that event, the

immediate British response would have been to counter-attack by sending

the army across the border with appropriate air support. Airfields were

therefore required in Northern Ireland to accommodate the RAF component

of this counter-invasion force and four were developed with that initial

purpose in mind. They were Sydenham, Long Kesh, Maghaberry and Blaris.

Two RAF light bomber squadrons, Nos. 88 and 226 were identified as the

Air Component and in June 1940 they arrived with Fairey Battle aircraft

at Sydenham. Being the pre-war civil airport as well as the site of a

rapidly expanding aircraft manufacturing industry, Sydenham was not the

ideal location. Due to shortage of space, and the airfield's

vulnerability to air attack (as demonstrated on 15 August 1940 when

Short & Harland's aircraft factory was bombed by the Luftwaffe and five

Stirling bombers were destroyed on the production line), there was an

urgent need for an emergency landing ground to which the 'planes could

be rapidly dispersed. This was obtained by the simple expedient of

taking over two large fields at Blaris, opposite the old graveyard,

which had been used occasionally in pre-war days for air displays or

private flying. Being a flat, firm, well-drained site with largely

unobstructed approaches, it was brought into use immediately as a grass

airstrip by the simple expedient of removing a few hedges and fences,

aircraft being dispersed in the open and personnel being accommodated in

tents. Records indicate that Fairey Battles and Anson aircraft from No

24 Elementary Flying Training School at Sydenham used Blaris in 1941,

and in due course the site came under the administrative control of Long

Kesh, being used for gliding instruction by the Air Training Corps from

1942 until the end of the war, under the direction of Wing Commander

Delap.

In comparison to Blaris, the development of Long Kesh

and its satellite airfield at Maghaberry proved considerably more

troublesome. Construction work on both sites did not begin until

November 1940, and although excellent progress was made with the

erection of buildings, runway construction was delayed by the large

amount of drainage and excavation work required, with the result that

both airfields were not officially opened until November 1941.

Contractor for the erection of buildings in both cases was H & J Martin,

while construction of runways was entrusted to the Royal Engineers at

Long Kesh and the firm of Sunley & Co. at Maghaberry. It is of interest

to note that on the dissolution of Sunley around 1942/43, the firm's

Northern Ireland interests were bought by Mr Sam Taggart and became

Farrans Ltd. of Dunmurry, who were involved in the construction of

Aldergrove, Toome, Maydown, Cluntoe and Bishopscourt airfields. After

the war Farrans obtained an aircraft hangar from Maghaberry and

subsequently re-erected it at their Dunmurry site where it stands to

this day.

While

Long Kesh and Maghaberry were being constructed, Nos. 88 and 226

Squadrons had meanwhile returned to England to re-equip with Blenheim

and American Boston aircraft. No.226 Squadron arrived with Blenheims at

Long Kesh in early October 1941, but returned again to England at the

end of November, their place at Long Kesh being taken by No.231 Squadron

which arrived from Newtownards with Lysander and Tomahawk aircraft. On

15 January 1942, No.231 Squadron moved to Maghaberry where it was based

until the following November, being replaced at Long Kesh by No.88

Squadron which arrived with Bostons for three weeks intensive training.

This included low-level close support of army exercises, during which

some of the more enthusiastic pilots succeeded in damaging several of

their new aircraft in low flying encounters with overhead cables! Other

army co-operation units in residence at Long Kesh for short periods

during the first half of 1942 included No.1494 Target Towing Flight with

Lysanders and No.651 Air Observation Post Squadron with Taylorcraft (Auster)

aircraft. On 24 January 1942, aircraft not normally associated with the

army co-operation role arrived in the shape of Spitfires of No.74

Squadron, but at Long Kesh during a cold spell of heavy snow and sleet

tactical co-operation with the army was the order of the day. In

addition, long-range fuel tanks were fitted to the Spitfires and the

squadron spent long hours escorting the convoys bringing American troops

to the United Kingdom by sea. No.74 Squadron left Long Kesh on 24 March

1942, taking with them unfortunate memories of bad weather, and one

particular event involving the Commanding Officer's Spitfire that seemed

to confirm their pre-conceived notions about the intelligence of the

local population. One day, when the Commanding Officer was at lunch, a

labourer employed in airfield construction dug a trench under the

Spitfire's fuselage with the result that it had to have its tail lifted

across the trench before it could be taxied away! While

Long Kesh and Maghaberry were being constructed, Nos. 88 and 226

Squadrons had meanwhile returned to England to re-equip with Blenheim

and American Boston aircraft. No.226 Squadron arrived with Blenheims at

Long Kesh in early October 1941, but returned again to England at the

end of November, their place at Long Kesh being taken by No.231 Squadron

which arrived from Newtownards with Lysander and Tomahawk aircraft. On

15 January 1942, No.231 Squadron moved to Maghaberry where it was based

until the following November, being replaced at Long Kesh by No.88

Squadron which arrived with Bostons for three weeks intensive training.

This included low-level close support of army exercises, during which

some of the more enthusiastic pilots succeeded in damaging several of

their new aircraft in low flying encounters with overhead cables! Other

army co-operation units in residence at Long Kesh for short periods

during the first half of 1942 included No.1494 Target Towing Flight with

Lysanders and No.651 Air Observation Post Squadron with Taylorcraft (Auster)

aircraft. On 24 January 1942, aircraft not normally associated with the

army co-operation role arrived in the shape of Spitfires of No.74

Squadron, but at Long Kesh during a cold spell of heavy snow and sleet

tactical co-operation with the army was the order of the day. In

addition, long-range fuel tanks were fitted to the Spitfires and the

squadron spent long hours escorting the convoys bringing American troops

to the United Kingdom by sea. No.74 Squadron left Long Kesh on 24 March

1942, taking with them unfortunate memories of bad weather, and one

particular event involving the Commanding Officer's Spitfire that seemed

to confirm their pre-conceived notions about the intelligence of the

local population. One day, when the Commanding Officer was at lunch, a

labourer employed in airfield construction dug a trench under the

Spitfire's fuselage with the result that it had to have its tail lifted

across the trench before it could be taxied away!

By

now it had become reasonably clear that there was little prospect of a

German invasion through the Republic, and new roles were being found for

Long Kesh and Maghaberry. On I April 1942 the United States Navy

commenced a thrice-weekly scheduled service between Elginton and Hendon

airfield in London, calling at Long Kesh to drop and collect passengers,

light freight and mail. The service was maintained until the end of the

war, initially by Lockheed 12 aircraft and subsequently by Douglas

Dakotas. The next development was a much more spectacular affair which

was however frequently interrupted by bad weather. This was a towed

glider service from Netheravon in Wiltshire to Long Kesh via the

shortest sea crossing from Portpatrick to Orlock Head, the aim being to

give glider crews and personnel of the Airborne Division experience in

long distance navigation and to test airborne equipment. The aircraft

generally used were Whitleyor Stirling aircraft towing Hotspur or Horsa

Gliders and the operations were not without incidents. On 11 August

1942, for instance, a Hotspur being towed by a Whitley had to be

abandoned in bad weather, the glider being damaged beyond repair when it

was forced to land in a small field near Lisburn. By

now it had become reasonably clear that there was little prospect of a

German invasion through the Republic, and new roles were being found for

Long Kesh and Maghaberry. On I April 1942 the United States Navy

commenced a thrice-weekly scheduled service between Elginton and Hendon

airfield in London, calling at Long Kesh to drop and collect passengers,

light freight and mail. The service was maintained until the end of the

war, initially by Lockheed 12 aircraft and subsequently by Douglas

Dakotas. The next development was a much more spectacular affair which

was however frequently interrupted by bad weather. This was a towed

glider service from Netheravon in Wiltshire to Long Kesh via the

shortest sea crossing from Portpatrick to Orlock Head, the aim being to

give glider crews and personnel of the Airborne Division experience in

long distance navigation and to test airborne equipment. The aircraft

generally used were Whitleyor Stirling aircraft towing Hotspur or Horsa

Gliders and the operations were not without incidents. On 11 August

1942, for instance, a Hotspur being towed by a Whitley had to be

abandoned in bad weather, the glider being damaged beyond repair when it

was forced to land in a small field near Lisburn.

On 26 August 1942 Long Kesh chalked up a novel

achievement when the first Stirling bomber produced by the Short &

Harland assembly plant, which had constructed the airfield some months

previously, took off on a trial flight piloted by HL `Pip' Piper. The

second Stirling to be produced was test-flown on 10 October and others

followed in due course. Stirlings were also test-flown from Maghaberry

where another assembly plant had been constructed. In fact, Short &

Harland used premises at various locations including Lisburn and

Aldergrove in connection with aircraft manufacture. Altogether 1,213

Stirlings were manufactured in Northern Ireland out of a total of 2,371

built and flown in the United Kingdom as a whole. Ironically, in the

immediate post-war period, several hundred Stirlings were stored on the

airfield at Maghaberry prior to being scrapped and melted down.

Tragically, not a single Stirling survives anywhere in the world

(although one hears persistent rumours about a number of them which are

reputedly buried in the Egyptian desert) � an unforgivable end to the

career of the first four-engined heavy bomber to be built for and

operated by the RAF in the Second World War.

At the end of 1942 came a new role for Long Kesh and

Maghaberry when they were taken over by Coastal Command's No.17 Group

for use by No.5 Operational Training Unit. Its function was to instruct

pilots and crews in the operation of Beauforts and Hampden aircraft. The

unit's initial establishment was thirty-three Beauforts which were based

at Long Kesh, and eleven Hampdens which were based at Maghaberry. No.5

OTU stopped using Maghaberry in August 1943 and Long Kesh in February

1944 by which time, in fact from October 1943, the Beauforts had been

replaced by Hudson, Ventura and Oxford aircraft. This was a welcome

development for the Beaufort's flying characteristics posed considerable

problems for inexperienced pilots and Beauforts based at Long Kesh were

involved in fifty-six serious accidents during 1943. In more than thirty

of these cases the aircraft were actually destroyed either as a result

of crashes at various locations throughout the Province, or failing to

return from navigation exercises over the sea.

Following

the departure of No. 5 OTU, Coastal Command had no further use for the

two airfields which were destined to fulfil different roles for the

remainder of the war. At Long Kesh, in March 1944, aircraft bearing

unfamiliar markings began to appear in the shapes of Seafires,

Swordfish, Wildcats and Hellcats belonging to a number of Royal Navy

Squadrons. The Navy Squadrons were in residence for relatively short

periods of no more than three months duration at different times up

until February 1945. They were on temporary absences from aircraft

carriers to enjoy a spell of rest or to exercise with army units and

practise anti-shipping or bombing strikes in the Lough Neagh and

Strangford Lough areas. One of the Royal Navy Squadrons based at Long

Kesh from October 1944 to February 1945 was No. 1882 Squadron, with

American Wildcat aircraft. During its time there, this particular

squadron was allocated responsibility for the air defence of Belfast

against the unlikely possibility of V 1 flying bomb attack. However, it

is perhaps best remembered for the flying skill of one of its 19-year

old pilots, Sub. Lt. Peter Lock who successfully ditched his Wildcat in

Portmore Lough on Christmas Eve 1944 after the aircraft had an engine

failure while en route to the bombing ranges in Lough Neagh. Readers of

the Star may recall that the aircraft concerned, JV482, coded

`60', was recovered from the Lough on 30 April 1984 in a combined

salvage operation involving the Ulster Aviation Society, the Ulster

Sub-Aqua Club, the Heyn Group, Belfast and No. 655 Squadron Army Air

Corps based at Ballykelly. The Wildcat has been restored by the society

and was inspected by Peter Lock and his wife Marjorie in January 1985

during the course of Peter's first visit to Northern Ireland since

leaving Long Kesh in 1945. Following

the departure of No. 5 OTU, Coastal Command had no further use for the

two airfields which were destined to fulfil different roles for the

remainder of the war. At Long Kesh, in March 1944, aircraft bearing

unfamiliar markings began to appear in the shapes of Seafires,

Swordfish, Wildcats and Hellcats belonging to a number of Royal Navy

Squadrons. The Navy Squadrons were in residence for relatively short

periods of no more than three months duration at different times up

until February 1945. They were on temporary absences from aircraft

carriers to enjoy a spell of rest or to exercise with army units and

practise anti-shipping or bombing strikes in the Lough Neagh and

Strangford Lough areas. One of the Royal Navy Squadrons based at Long

Kesh from October 1944 to February 1945 was No. 1882 Squadron, with

American Wildcat aircraft. During its time there, this particular

squadron was allocated responsibility for the air defence of Belfast

against the unlikely possibility of V 1 flying bomb attack. However, it

is perhaps best remembered for the flying skill of one of its 19-year

old pilots, Sub. Lt. Peter Lock who successfully ditched his Wildcat in

Portmore Lough on Christmas Eve 1944 after the aircraft had an engine

failure while en route to the bombing ranges in Lough Neagh. Readers of

the Star may recall that the aircraft concerned, JV482, coded

`60', was recovered from the Lough on 30 April 1984 in a combined

salvage operation involving the Ulster Aviation Society, the Ulster

Sub-Aqua Club, the Heyn Group, Belfast and No. 655 Squadron Army Air

Corps based at Ballykelly. The Wildcat has been restored by the society

and was inspected by Peter Lock and his wife Marjorie in January 1985

during the course of Peter's first visit to Northern Ireland since

leaving Long Kesh in 1945.

In March 1944, No.290 Squadron, RAF, arrived at Long

Kesh from Newtownards equipped with Martinets, Oxfords and Hurricanes.

Its commitment was to provide all the anti-aircraft co-operation

training for the whole of Northern Ireland for the navy, army, RAF

regiment and gunnery school at Greencastle airfield near Kilkeel

operated by the United States Army Air Force. This kept the aircraft

extremely busy although the work-load eased considerably after the

Normandy invasion, and in August 1944 the Squadron was transferred to

Turnhouse near Edinburgh leaving only a small detachment at Long Kesh

which rejoined the squadron in Scotland in Februry 1945.

Thereafter the airfield went into a period of

relative inactivity, punctuated by short-lived diversionary and social

visits involving aircraft rarely seen at Long Kesh, including USAAF

Mustangs, Thunderbolts and B-17 Fortresses which were considerably in

evidence during the summer of 1945.

But the event which attracted most attention was the

arrival from Hendon on 17 July of three Dakotas bearing their Majesties

the King and Queen, HRH the Princess Elizabeth, their entourage and

accompanying press corps, for the first royal visit to Northern Ireland

by air. Their Majesties stayed at Government House in Hillsborough for

two days before continuing their journey by air to Eglinton on 19 July.

Other distinguished visitors who passed through Long Kesh included

General Eisenhower and Field Marshal Montgomery, in August and September

1945 respectively.

LONG KESH AERODROME

Local people always called this area Halftown, and it was the government

who named it Long Kesh. Thompson Crossey recalls this period.

When the Second World War broke out the Air Ministry

decided to build an aerodrome at what was to be known as Long Kesh.

Building started in 1941 and the aerodrome was used until approximately

1947. This gave a great deal of employment to the local people. Most of

the concrete was wheeled in barrows to make the runways. Extra money

meant that the local men could meet more often in the pub (Annie

Ritchie's) and it was always said that they brought more cement into the

pub than would have built another runway. An old saying developed among

the men at the 'Corner', "Rough Concrete ".

The aerodrome also provided many other interests.

Annie Berry, Madeline McNally, Sarah Hewitt and Norah Higginson all

married airmen. The picture house at the aerodrome was also very

welcome. Mary of the locals went to the pictures on Wednesday night and

Sunday night. There were also sports days between the army and airforce.

MILITARY HOUSING

The advent of the Second World War made its mark on the area and major

changes ensued. The people who lived in the area now known as Long Kesh

had their property and land compulsory acquired. The building of runways

began, homes were demolished, top soil removed, land drained to River

Lagan and loads of stones from local quarries arrived by lorry. From the

employment provided to build an airfield, the erection of a railway

halt, to temporary housing, life was different. To accommodate the

military personnel temporary housing, in the form of `huts', was built

down the Dummies (Eglantine Road). To the local people it was `Tin

Town', portraying the materials used in building. This enclave became

the starter homes for most young people in the aftermath of the War, but

also

housed large families. Along the avenue to Eglantine

church, huts were built, as well as a de-contamination centre and a

hospital. The inevitable air raid shelters were also in this area. At

Spratt's farm there was a Kitchen, Canteen, Cinema and Sports Centre. To

recall `tin town' will bring happy memories to many people.

Delivery men had some trouble when Coronation Gardens

housing estate was built beside Long Kesh Aerodrome, constantly

confusing it with Long Kesh `huts' (some 2 miles away) beside what is

now Lisburn Golf Club.

BLARIS ROAD

This road goes east to Warren Gate Bridge at Sprucefield. History shows

that armies camped in this area, on the sandy soil and near the River

Lagan. Blaris Old Graveyard, an ancient burial ground, is on this road.

DEMIVILLE

During

the 19th century most of the people living on Long Kesh were farmers.

There was also a tradition of hand-loom weaving. With changing economic

circumstances the weavers found employment in the quickly established

linen industry and in the expanding building trade. The farmers who

remained on the land adapted to market gardening to supply the demand

for vegetables from the rising number of new urban dwellers who worked

long hours. Hence Demiville became established as a market gardening

centre, providing employment. The soil of the Lagan Valley was easily

worked, and the proximity to Belfast Market was an added advantage. The

people in charge of operations exploited every opportunity as The

Northern Whig records in September 1836: During

the 19th century most of the people living on Long Kesh were farmers.

There was also a tradition of hand-loom weaving. With changing economic

circumstances the weavers found employment in the quickly established

linen industry and in the expanding building trade. The farmers who

remained on the land adapted to market gardening to supply the demand

for vegetables from the rising number of new urban dwellers who worked

long hours. Hence Demiville became established as a market gardening

centre, providing employment. The soil of the Lagan Valley was easily

worked, and the proximity to Belfast Market was an added advantage. The

people in charge of operations exploited every opportunity as The

Northern Whig records in September 1836:

Messrs. Moreland, Robinson & Co., of Hillsborough, in

conformity with their proposal of giving as a premium a cask of whiskey

to the farmer who produced the greatest quantity of mange/ wurtzel to

the acre, had sent home to Mr William Shaw of Demiville, a ten-gallon

keg of good old Hillsborough spirits. We look upon this praiseworthy act

in the givers as by making the offer they promoted the .farmers

in the neighbourhood to deeds of honourable emulation in cultivating a

crop with which now has been nearly unknown to them and which, we have

no doubt, will in a short time introduced a new. feature in

agricultural science in this party of the country.

We congratulate Mr. Shaw on his success, assured that

the keg could not have fallen into hands more deserving or to

one who would make a better use of its contents; and we proceed to trust

that this speculation of manufacturing sugar from beet-root may equal

the expectations of Messrs. Moreland, Robinson & Co., its spirited

projectors in Ireland, not only on account of its being a benefit to

themselves individually but also on account of the advantage which will

be derived from this new crop by the tillers and cultivators of the

soil.

BOG ROAD

In

the 18th and 19th centuries this area was where turf was cut for fuel.

Buchanan's brick works was approached off this road, whilst In

the 18th and 19th centuries this area was where turf was cut for fuel.

Buchanan's brick works was approached off this road, whilst

Braithwaite's brick works was on the Halftown Road.

When the Second Word War started all the accumulated stacks of bricks

were requisitioned immediately.

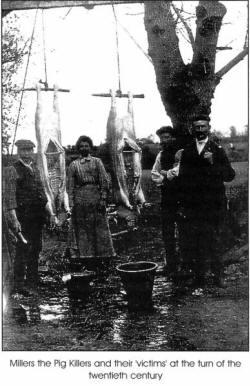

One person always associated with the Bog Road was Mr

William (Billy) Miller `the pig killer'. In every district there was

`pig killer' and Mr Miller served the area well. Not only did he kill

pigs, but he also dressed the male piglets and cut the tails of all the

piglets. When the pig was fat the owner sent for the `pig killer'.

In days gone by killing pigs was a savage operation,

not for the faint hearted. When the pig killer arrived on the premises

there had to be plenty of boiling water. There also had to be a beam,

suspended on two upright poles, at least 12 to 15 feet above the ground.

The pig killer entered the shed where the pigs were kept and snared a

pig, using a short rope and brought it to a spot beside the beam.

The owner held the rope tight, holding the pig's head

up, and the pig killer then hit it on the head with a small hammer

causing it to fall on its side and proceeded to cut its throat ('stuck

the pig'). Hot water was then poured all over the pig and it was scraped

with a razor sharp knife until it was white. The pig was then hung on a

beam by its hind legs and the `pig killer' then slit its stomach from

top to bottom. As the entrails fell out he caught them in his arms and

set them on the ground. He then sorted out the different bits and

pieces.

People in the village were able to buy fresh liver

and other pig meat from the owner. It was common practice for the boys

of the village to get the pig bladders and blow them up with a bicycle

pump and make footballs with them. When the pigs had been hung for three

days they were taken to market or to the bacon curers.

During the eighteenth century and halfway through the

nineteenth century it was customary for people living the country to

feed the pigs on `swill', which was the leftovers from the tables of the

village houses. It was collected every morning and boiled in a large pot

and then a little meal was added.

SERVICE TO OUR COUNTRY

THE FIRST WORLD WAR

Looking at places in a village gives us some idea of the context in

which people lived, worked and played. At the end of the day it is

really the people who make a place, whether they strove to achieve great

things, or simply left their mark by quiet devotion to family, friends

and work. Culcavey and Halftown, just like anywhere else, have seen a

fair share of people involved in the tragedy of war, those involved in

maintaining the traditions of past generations and those who, quite

simply were `characters'.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission registers make

painful reading, reminding us of the futile waste in various parts of

the world of young lives. At the beginning of the twentieth century the

people of Europe really still had little idea of the universal

destruction which war could bring. All that was to change with the

horror of the First World War (1914-18). Historians would dispute the

numbers killed in this war, but few would deny that there was not a

corner of Britain which was not touched by the bitter taste of loss.

Culcavey and Halftown are no exceptions. The memorial plaque in All

Saints' Eglantine Church and the war memorials in Hillsborough and

Lisburn record the loss of the following local men:

RIFLEMAN JAMES ANDREWS

James Andrews, a native of Culcavey, served in the 13th Battalion of the

Royal Irish Rifles. He died on the first day of the Somme, l st July

1916, at the age of 18, and was laid to rest in Connaught Cemetery,

Thiepval, France. James was a sister of Sophia Smyth (nee Andrews) who

lived at Glen Cottage and Grey Row, Culcavey.

RIFLEMAN WILLIAM JOHN BERRY

William John Berry, son of Mary and James Berry served in the 13th

Battalion of the Royal Irish Rifles. He was 27 years old when he was

killed on 29th June 1916. WJ Berry was buried in Forceville Cemetery at

the Somme.

PRIVATE OLIVER CROSSEY

Oliver Crossey was the son of William and Susan Crossey of Thompson's

Row. Like so many young men he had joined the army believing that he was

fighting for king and country and had entered the 13th Battalion of the

Royal Irish Rifles. Far from the familiar scenes of little Culcavey, he

was to lose his life on Friday, 30 June 1916, on the eve of the infamous

Battle of the Somme. He was just 20 years old.

His grave is in Puchevillers British Cemetery at the

Somme. In June 1916, before the Battle of the Somme, the 3rd and 44th

Casualty Clearing Stations came to Puchevillers and began to prepare

grave plots. Even General Haig, one of the architects of the British

offensive at the Somme, had anticipated great losses, and this creation

of graves suggests that this feeling was widespread. By 1918 the

cemetery at Puchevillers had 2,000 plots. To the British army Oliver

Crossey was Private 16353, but in Culcavey he was a young local man,

known to many. Even amidst the awful carnage of this war, this is still

a sobering thought.

RIFLEMAN THOMAS HENRY EMERSON

Thomas Henry Emerson served with C Coy., 14th Battalion of the Royal

Irish Rifles. He died on Wednesday 20th June 1917 at the age of 23. A

son of William and Agnes Emerson of 11 Zetland Street, Belfast, he was a

native of Culcavey.

RIFLEMAN SAMUEL KANE

Samuel Kane served in 13th Battalion of the Royal Irish Rifles and lost

his life on Saturday l st July 1916, at the Battle of the Somme. His

death is recorded at the Thiepval Memorial, Somme, France.

RIFLEMAN SAMUEL LYTTLE

Another soldier in the Royal Irish Rifles, he was only 24 when he

was killed on the first day of the Battle of the Somme (1st July 1916).

Samuel Lyttle's death is recorded on the Thiepval Memorial, Somme. He

was the son of Arthur and Mary Lyttle.

PRIVATE S J MACAULEY

Private SJ Macauley served in the 15th Batallion Canadian Infantry

(Central Ontario Regiment). He died on Sunday 20th October 1918 and is

buried at Auberchicourt British Cemetery Nord, France. Auberchicourt is

a village 11.5 kilometres east of Douai on the road to Valenciennes. The

cemetery is one kilometre west of the village on the northside of the

road to Erchin, 300 yards away from the Communal Cemetery. The village

was occupied by British troops in October 1918 and the cemetery was

begun at the end of that month and used until February 1919, while the

6th, 23rd and 1st Canadian Casualty Clearing Stations were in the

neighbourhood. The original graves are in Plot 1, but the cemetery was

enlarged after the Armistice by the concentration of graves from the

surrounding battlefields and from smaller burial grounds. The following

Canadian graves were taken to Auberchicourt British Cemetery:

Auberchicourt Churchyard in which one Canadian soldier was buried in

1918; Montigny British Cemetery (Nord, East of Douai) near the

south-west angle of the Bois de Montigny, 20 Canadian soldiers; Somain

Communal Cemetery which contained the graves of seven Canadian soldiers

who fell in October 1918; and Wallers Communal Cemetery Extension in

which nine Canadian soldiers were buried in October 1918.

SERGEANT ROBERT McCARTHY, MM

Robert McCarthy served in the 2nd Battalion of the Irish Guards and was

killed on Friday 15th September 1916. His death is recorded on the

Thiepval Memorial, Somme. Robert was employed as a Printer by the

Lisburn Herald and was a member of the Royal Irish Constabulary prior to

joining the army. He was posthumously awarded the Military Medal in

recognition of his bravery. By leaving the safety of the trenches he

attempted to rescue awounded officer and was bringing him to safety when

a German shell exploded killing both men.

RIFLEMAN THOMAS MERCER

Thomas Mercer was the husband of Margaret Mercer of Culcavey and he

served in the 13th Battalion of the Royal Irish Rifles. He was killed on

28th June 1916 at the age of 34, and was buried in Martinsart Cemetery

at the Somme.

RIFLEMAN A. NEILL

A. Neill served in 20th Battalion of the Royal Irish Rifles and died on

Thursday 10th August 1916. He is buried at Blaris (Old) Graveyard where

there are 5 Commonwealth burials of the 1914-18 war.

RIFLEMAN WILLIAM NELSON

William Nelson served in 11th Battalion of the Royal Irish Rifles and

lost his life on Saturday 1st July 1916. His death is recorded on the

Thiepval Memorial, Somme.

SERGEANT JOSEPH PENTLAND

Joseph Pentland served in 6th Battalion of the Royal Irish Fusiliers and

died on Sunday 15th August 1915 aged 35. He was the husband of Agnes

Graham Pentland of Lisburn Street, Hillsborough and served in the South

African War. His death is recorded on the Helles Memorial, Turkey.

LANCE CORPORAL ISAIAH SINGLETON

Isaiah Singleton served in 1st Battalion of the Irish Guards and died on

Sunday 1st November 1914 at the age of 23. He was the son of Isaiah and

Mary Ann Singleton of Halftown, Maze. Death is recorded at Ypres (Menin

Gate) Memorial.

LEADING CARPENTER'S CREW JOSHUA SINGLETON

Joshua Singleton served on H.M.S. "Cressey", Royal Navy. His death at

the age of 37 is recorded on the Chatham Naval Memorial, Kent. Joshua

was the son of David and Eliza Jane Singleton of Halftown, Maze, and

husband of Elizebeth Singleton of the same address.

The sinking of the Cressey marks one of the largest

losses of crew in naval combat in World War One. During the early months

of the war the Royal Navy maintained a patrol of old Cressy class

armoured cruisers, known as Cruiser Force C, in the area of the North

Sea known as the Broad Fourteens. There was an understanding that the

ships were very vulnerable to raid by modern German surface ships and

the patrol was nicknamed the "live bait squadron". They were maintained

because the destroyers were not able to patrol in the frequent bad

weather.

In the early hours of September 20th 1914 the

cruisers Euryalus, Aboukir, Hogue and Cressy prepared to go on patrol

under Rear Admiral Christian in HMS Euryalus. The weather was bad and

the Euryalus dropped out due to lack of coal and weather damage to her

wireless. Command was delegated to Captain Drummond in Aboukir, although

it was not made clear to him that he had the authority to order the

destroyers to sea if the weather improved, which it did at the end of

21st September.

Patrols were supposed to maintain 12-13 knots and

zigzag, but the older cruisers were unable to maintain that speed and

zigzagging was widely ignored. Early on 22nd September 1914 the German

submarine U9 under the command of Commander Otto Weddigen sighted the

Cressy, Aboukir and Hogue steaming NNE at 10 knots without zigzagging.

U9 manoeuvred and at about 6.25 a.m. fired a single torpedo at Aboukir,

striking her on the port side. Heavy flooding, listing and loss of

engine power caused Captain Drummond to abandon ship. He thought the

Aboukir had been mined and signalled the other two cruisers to assist,

realising too late that it was a torpedo attack. Half an hour later two

torpedos hit HMS Hogue amidships, rapidly flooding her engine room.

Captain Nicholson of Hogue had stopped the ship to lower boats to rescue

the crew of Aboukir. The ship was attacked from a range of only 300

yards. Ten minutes later the Hogue sank and the same fate was meted out

to the Cressey. Cressy, under Captain Johnston, had also stopped to

lower boats but got underway after sighting a periscope. At about 7.20

a.m. two torpedoes were fired, one missing and the other hitting the

Cressy on her starboard side. The Cressy returned fire with no avail,

and although the damage was not fatal the U9 turned round and fired her

last torpedo that sank the Cressy within a quarter of an hour.

Survivors were picked by several merchant Dutch and

British trawlers before the Harwich force of light cruisers and

destroyers arrived. In all 837 men were rescued but 1459 died, many of

which were reservists or cadets.

RIFLEMAN JOHN SMITH

John, the son of Joseph and Elizabeth Smith of Eglantine, served in C.

Coy. 13th Battalion, Royal Irish Rifles. He lost his life on Thursday

29th June 1916 at the age of 20. His grave is at Forceville Communal

Cemetery and Extension, Somme, France.

RIFLEMAN THOMAS THOMPSON

T. Thompson served in 13th Battalion of the Royal Irish Rifles. He died

at the age of 27 on 10th October 1917 and is buried at Wimereux Communal

Cemetery Pas de Calais, France. His parents were Thomas and Mary

Thompson of Hillsborough.

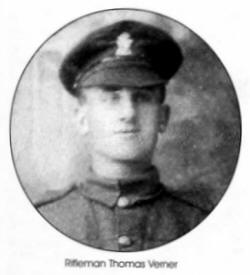

RIFLEMAN THOMAS VERNER

Thomas Verner, the son of Joseph and Elizabeth Verner, Halftown, lost

his life on Monday 28th October 1918 aged 27. He served in 12th

Battalion, Royal Irish Rifles and is buried at Terlincthun British

Cemetery, Wimillepas de Calais, France. Thomas Verner, the son of Joseph and Elizabeth Verner, Halftown, lost

his life on Monday 28th October 1918 aged 27. He served in 12th

Battalion, Royal Irish Rifles and is buried at Terlincthun British

Cemetery, Wimillepas de Calais, France.

LANCE CORPORAL WILLIAM WATSON

William Watson served in 2nd Battalion of the Royal Irish Regiment.

His death is recorded at the Thiepval memorial, Somme. He died on Sunday

3rd September 1916. One other local man, T. Watson, who

served in the Royal Irish Rifles is also recorded. Unfortunately no

information on him has come to hand. The Roll of Service in Eglantine

Church names those who survived the action:

| George Acheson |

William George McCoy |

| James Acheson |

George McLorn |

| Joseph Cheshire |

William Magill |

| Edmund Freel |

John Morgan |

| Francis Freel |

Robert Pentland |

| Stephen Gray |

Adam Pentland |

| Robert Hanna |

John Presha |

| William Hanna |

Alexander Robinson |

Other local men known to serve King and Country were

Jimmy McNally, Tom Kane, Nelson Hewitt, Herbert Lowry, Thomas Singleton

and Wilson White, Snr.

|