|

REMINISENCES

MEMORIES OF MY CHILDHOOD

Tom Patterson recalls how different life was in his

youth.

Mine was a home birth in the twenties, and in the

1920s and 30s few mothers-to-be went to hospital, thus the local midwife

known as Nurse Watters brought me into the world. Nurse Watters was an

institution in her own right. She went from home to home on her bicycle

and lived in a house at what is now known as Long Kesh. She had one

daughter; and was herself very hard of hearing. As I grew up

I remember her calling at our home to converse with my mother; they each

spoke at the top of their voices. In those clays, Nurse Watters' bicycle

outside a house generally meant that a baby was on its way. Her bicycle

had a little basket on the .front. I remember its

leaning against the hedge outside our home. Mine was a home birth in the twenties, and in the

1920s and 30s few mothers-to-be went to hospital, thus the local midwife

known as Nurse Watters brought me into the world. Nurse Watters was an

institution in her own right. She went from home to home on her bicycle

and lived in a house at what is now known as Long Kesh. She had one

daughter; and was herself very hard of hearing. As I grew up

I remember her calling at our home to converse with my mother; they each

spoke at the top of their voices. In those clays, Nurse Watters' bicycle

outside a house generally meant that a baby was on its way. Her bicycle

had a little basket on the .front. I remember its

leaning against the hedge outside our home.

My earliest memories were of fetching and carrying.

Newport was really just a little hamlet of houses, with no running

water; no electricity and dry toilets. There was a water pump by the

side of the road where everyone got their water. Water was carried in

buckets, and if you had two you made yourself a wooden frame, possibly

three feet square, placed it with a bucket on each side and the carrier

walked in the middle. The local people maintained the pump, only

requiring a piece of leather to be put round the `sucker' every now and

then.

All children played together in those days, games

such as 'hunt the deer', `marbles', rolling bicycle wheel

rims (hoops), and looking for bird nests occupied the long summer clays.

Living so near the Lagan Canal (now part of the

motorway) meant we fished and bathed in it in the summer; and in the

winter when it was frozen over we played on it. Winters were severe in

those days. Some of the families that made up Newport in the 1930s and

1940s were: Mulholland; Armstrong; Singleton; McGuigan; McCoy; Finn;

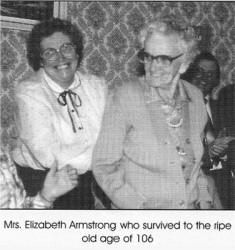

Hanna; Thompson; Jeffrey; Patterson; Fleming; Nicholl; Reid.

Everything had to be carried. At a very young age I

was sent for the milk each evening to the McCord 's farm. You went up

the lane through the railway bridge (still standing) with a tin can. Mrs

McCord would then take the tin from you and go to a large brown crockery

container (crock) and measure you a ladle full of milk. Each Saturday

you took the few pence to pay for the weeks supply. My elder sister

would have had to walk up to the shop where Mr Emerson made up your

order while you waited. Cars were few in the early

thirties, and when we saw one we often just stood and stared.

Boats going up and down the canal were also a source

of interest. Some were pulled by horses, a few had engines. Those that

had engines often had another barge in tow.

My family, the Pattersons, were sent to Hillsborough

Presbyterian School because the then headmaster, Mr McCready, asked my

.father to send us to keep the numbers up, thereby

keeping his wife in her job as a teacher in his school. I can remember

the embarrassment we felt as we met the Culcavey children coming down

the road to Newport School as we walked up the road one-mile to

Hillsborough. On looking back, it was a silly arrangement.

We walked everywhere, and I remember wearing boots -

no shoes. Clothing was handed down. As 1 was the second in the family I

had to wear my sister's Burberry coat as she grew out of it.

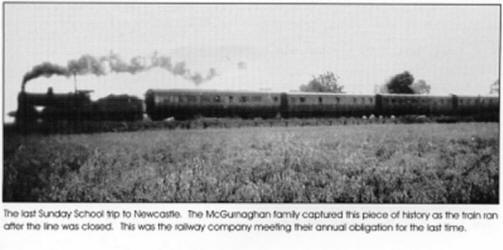

Holidays away from home were unknown. A day to

Newcastle (usually the Sunday School trip) was quite an event and much

looked forward to. In the 1930s and 1940s it was by train from

Hillsborough Station. Carriages were just added on to the normal

scheduled run. Very often several parties of children and their parents

were accommodated on the one train. Church parties from Lisburn and

Dunmurry were often together on the day outing to Newcastle. It took a

long time to cover the 26 miles of track, as the train would stop at

every little halt. I well remember the stationmaster walking up and down

shouting `Ballyroney' or some such place. Mothers had a hard day as

everything was packed into carrying bags for the journey.

Those who had gardens always worked them. Potatoes

and soup vegetables were the main crop. No artificials or pesticides

were ever used, just the spade, the fork and farmyard manure. In Newport

I remember the timid competition between the older men who had gardens;

it was always a source of conversation.

The radio, or wireless as it was then called, was a

prized possession. I remember our .first one well. We

listened to the fights as they were described blow by blow; and as war

approached our parents listened with apprehension. My father was a

veteran of the 1914-18 war and carried a war wound all his life, for

which, if I remember correctly, gave him a pension of �1 and 2 shillings

a month. He would let his pension accumulate, for a

few months and then my brother and I accompanied him into Tommy Duncan's

boot and shoe shop in Lisburn, where he would buy us boots, striking of

course the best price possible. `Haggling' was what they called it. The radio, or wireless as it was then called, was a

prized possession. I remember our .first one well. We

listened to the fights as they were described blow by blow; and as war

approached our parents listened with apprehension. My father was a

veteran of the 1914-18 war and carried a war wound all his life, for

which, if I remember correctly, gave him a pension of �1 and 2 shillings

a month. He would let his pension accumulate, for a

few months and then my brother and I accompanied him into Tommy Duncan's

boot and shoe shop in Lisburn, where he would buy us boots, striking of

course the best price possible. `Haggling' was what they called it.

I remember the wildlife of my childhood. There were

always swans and water hens on the canal, and in the really hot weather

pike would come to the top of the water, where we would flip them out of

the water onto the bank. There were also roach and large frogs in the

canal. Rabbits and hares were aplenty, especially along the railway

banks. Songbirds were in abundance and as a very young boy I remember

listening for hours on end to corncrakes answering each other

The trains and the, factory horn

were very much a part of our lives. Each time a train passed our bedroom

the windows rattled and we went to sleep and rose according to their

timetable. There was the ten past seven, the eight o'clock in

the morning, and so on. Very often there was no need to look at the

clock, the factory horn or the train told you the time of day.

The pace of life was leisurely and crime, such as it

was, was confined to being caught without a tail lamp on your bike. I

remember as a very young boy walking to school past Hillsborough Railway

Station and literally dozens of bicycles were lying on the grass banks

around the station. It seems few, if any, were stolen in those days.

Another recollection of the Halftown as a young boy

was of being sent down to buy paraffin oil off the Morgan family whose

house was on the left 500 yards past Newport School. George Hamlin also

had a smallholding, where he reared and fattened chickens and hens for

the market. I would have been given a purse with some money and sent

down for a 'boiling fowl'. He would kill the bird in front of

me, very expertly, put the change in the purse, hand me the still

kicking bird, and I would return home via the canal towpath.

The families of Halftown that most come to my mind

are: Berry; Palmer; Watters; Morgan; Beattie; Martin; Miller; McMinn;

Lappin; Scott; Finlay; Bingham; Kennedy; Hunter; McKelvey; Auld.

CHILDHOOD MEMORIES OF SUNDAY SCHOOL

Religious education and institutions formed an integral and vital part

of life in a by gone era. Bertie Emerson recalls his vivid memories of

his Sunday School days.

Every Sunday morning we were dressed in warm clothing

and hand-sewn boots made by Mr Turley, the cobbler from Hillsborough.

Off we went to Sunday School at Maze Presbyterian Church, which was more

than a mile away.

Out through the gate the six of us trooped on `Shanks

mare'. At Culcavey crossroads we took the Puddledock Road,

where we found other families from the village going to church. There

were rows of us, all across the road. Onward we went avoiding the

puddles until we reached Jackdaw Corner. Around this corner grew many

tall trees, with branches which hung over the road. Their trunks were

entwined with ivy which made them seem eerie. The jackdaws had built

their nests of twigs high up in the branches. On we went, a happy band,

and the noise we made attracted the animals in the fields, and they too

came to the side of the road and accompanied us on the inside of the

hedge as far as the fences allowed.

Below the high ground on the left was the site of the

original Methodist Meeting House (Priesthill), named after an area on

top of the high ground. There was a monkey puzzler tree in front of

Basil McApherson's house. Basil was the only man I knew who rode an

adult tricycle.

At Hooks Corner; turning right, we passed the second

site of the Methodist Church called Zion. This is a symbolic name for

the dwelling house of God. Recently after extensive improvements this

church has taken back its original name, Priesthill. We went over the

hump-backed bridge which spanned the canal, arriving at Sunday School.

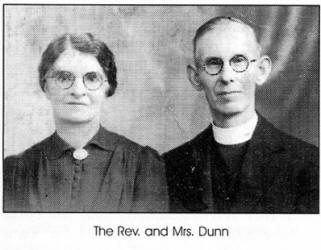

The Rev Dunn was a tall thin man, with a kind and

compassionate manner. He wore gold-framed glasses and a pork-pie hat.

This hat was so called because of its fanciful resemblance to a pork

pie, and was normal headgear for our ministers at that time. The Rev and

Mrs Dunn taught in Sunday School as well as several other teachers. At

no time was there a shortage of people capable and willing to teach

scripture. We learned by listening, singing, reading and repetition.

Passages of scripture, psalms and hymns were learned by heart as well as

the shorter Catechism. The class lasted one hour The Rev Dunn was a tall thin man, with a kind and

compassionate manner. He wore gold-framed glasses and a pork-pie hat.

This hat was so called because of its fanciful resemblance to a pork

pie, and was normal headgear for our ministers at that time. The Rev and

Mrs Dunn taught in Sunday School as well as several other teachers. At

no time was there a shortage of people capable and willing to teach

scripture. We learned by listening, singing, reading and repetition.

Passages of scripture, psalms and hymns were learned by heart as well as

the shorter Catechism. The class lasted one hour

At the end of the year we had an oral examination. I

can recall sitting at a rectangular table, at the end of which was a

paraffin oil lamp which gave out a bright light. This was my first exam,

and opposite me sat the examiner, the Rev David Hay of First Lisburn. I

could see he was wearing a dark suit and the traditional white collar

which encircled his neck. He looked gigantic, and the glow of the light

cast a long shadow on the end wall. The movements of his hands and head

caused the shadow to dance. My teacher pushed my chair close to the

table, for safety reasons no doubt. There I was, wedged in, just the two

of us in the room. As the Rev Hay looked across the table, he would only

see a small head, which I hoped would know the answer The first question

was "What is man's chief end?" I answered that one correctly, and a few

others as well. To some I answered, "I don't know".

The big social events of the year were the excursion

by train from Hillsborough Station to Newcastle, the congregational

social and the Christmas party.

There was a thirty-minute interval between the end of

Sunday School and the commencement of the church Service. League of

Church Loyalty Cards for attendance were stamped. We normally went into

church, but if we had been told there was an open grave in the

graveyard, behind the church, we would go and see it because we would

have known the bereaved family. From a safe distance we looked at the

large pile of soil, and marvelled at the straight sides of the grave.

Many boys and girls knew the sorrow of death and had witnessed the

funerals of their brothers, sisters or parents.

The service commenced at mid-day and lasted at /east

one and a half hours. The Emersons sat on the left-hand side of the

Church. There were doors on the pews, and the aisles were the only parts

of the floor that were covered with cord carpet. Light was by oil lamps

suspended down from the ceiling. Later on these lamps were replaced by

electric light. This unadorned meeting house was in a non-conformist

style.

We carried our bibles and hymnbooks with us. Our

Sunday School teachers, the Misses Campbell, sat in the pew in front of

us � their brother was a blacksmith. On the wall behind the pulpit, and

high above the minister head, was painted in capital letters "WORSHIP

THE LORD IN THE BEAUTY OF HOLINESS".

An American organ provided music, and the organist

had to pedal fast 'to get the wind up' as it was colourfully

described. Had this not been so, the music would have sounded as though

the organ had laryngitis. The tempo of singing was slow; nevertheless it

was loud and sincere. We sang `Amen' at the end of each praise. Anthems

were a feature at special services and Harvest services. For the Harvest

the church was decorated with locally grown produce. Each year a frieze

of corn stalks about 18 inches deep and a foot thick was strung around

the pulpit. Grapes and bananas purchased from the shops hung over the

corn, and four or five stems of pampas grass stood guard at either side.

A smaller frieze of corn surrounded the choir stall.

Communion was celebrated twice per year: The church

was always packed, every family in their pew. We knew them all and they

knew us. The men wore dark three-piece suits, the waistcoats

of which were adorned with gold watch, pendant and chain. The ladies

wore their Sunday best, and crowned it all with a hat. When the minister

began his sermon, which we called `the long bit', the elderly men would

stretch their legs, lean back and close their eyes. I thought they were

asleep. Then we would nudge each other and smile. But the men were not

asleep. Silence reigned supreme and you could have heard a pin drop. No

one knew about microphones or loud speakers. Silence and closed eyes

increased your power q f comprehension. The Rev Dunn announced his text;

a passage taken from the Bible served as a theme to preach upon. He

elaborated on it and related it to everyday life according to the

scriptures. His sermon also had a moral teaching 'Honour thy father and

mother that their days may be long in the land that the Lord thy God

giveth thee'.

Another man who came to church fascinated me. He was

always late. He was tall and had his long white hair swept back. He sat

at the front. We knew him as `Tipperary Tim'. He was a

wanderer and slept under a starry sky. I imagined that he knew

everything about the flora and fauna of the countryside. He would leave

as we started to sing the last hymn. Tim was possibly closer to nature

than anyone else in the congregation, but he was just like the rest of

us. Everybody came because they realised the need to experience the

satisfaction of public worship. I saw Tim one sunny Sunday in May, and

thereafter no more. He had gone to his great reward.

When the sermon was over; the collection was lifted,

always by the same men. You put your money in a round wicker basked

lined with red soft felt. The baskets were placed on a seat behind the

organist. After singing the last hymn the Rev Dunn raised his right hand

and pronounced the Benediction. "NOW MAY THE BLESSING OF THE LORD AND

SAVIOUR JESUS CHRIST REST UPON AND ABIDE WITH YOU ALL, BOTH NOW AND

EVERMORE." We did worship the Lord in the beauty of holiness.

CULCAVEY 1934-1950

Thompson Crossey recalls characters and lifestyles in the district

before and immediately after the Second World War.

When I think back to my youth my immediate recall is

of the many characters that made up the village of Culcavey. From the

people who supplied the daily needs of the village, the source of

income, education and christian teaching, right down to the ordinary

working class men and women who were so much a part of my life.

It is difficult to make a starting point, so I will

recount as things come to memory.

My grandfather, William Crossey, came to Culcavey

.from Sandy Row, Belfast, and resided at No.10 Thompson's

Row. He worked on the Titanic in the shipyard, riding a bicycle there

and back to Culcavey. It was said that he grew the biggest leeks in the

country. He also worked with Johnstone the Lambeg Drum makers in Sandy

Row and brought a drum called `The Darkie' to LOL Lodge 111, Lower Maze.

This drum was reputed to be the best Lambeg drum in the country and it

is still in Lower Maze Orange Hall.

School was Newport Primary, where Mr JJV Boyd ruled

as Headmaster assisted by Miss Beattie. Between them they taught all the

children of the village and surrounding area. Mr Boyd came

from Athlone and he spoke with a brogue.

The main source of employment was the factory, or

Hillsborough Linen Company. Workers were alerted by a factory horn at

7.30 in the morning. At 8 o'clock the horn blew again signalling a start

to work. At 12.30 it sounded again for dinner and at 1 o'clock it again

signalled a start back to work. It echoed out again at 6 o'clock

to stop work for the day. The entire village used the horn as

their time guide. Times were hard for the workers. Bad batches of yarn

were the main reason for pay and argument. Some weavers blamed the `tenter'

for giving them a bad `beam'. On one occasion I remember quite clearly

my mother coming home with just sixpence in her pay bag. Pa McCandless

was the manager of the factory. He was feared and respected by most of

the workers, but was a fair man. When l started off in the `scrap

business' I operated between the gables of Thompson's Row and Puddledock

Row, what was in effect factory land. I worked here in the evenings

after having done my stint at Mackies in Belfast. Obviously someone must

have reported my making use of the land and I received a visit from Pa.

He arrived one evening and caught me at work, pointed out that I

shouldn't be carrying on my operations there and queried my working

hours. I told him I caught the 7.00 a.m. bus at the corner and arrived

home on the 6.00 p.m. at night. He commented on my hard graft and that

was the last I heard of the matter. Indeed a fair and just man who could

recognise a man's worth! The main source of employment was the factory, or

Hillsborough Linen Company. Workers were alerted by a factory horn at

7.30 in the morning. At 8 o'clock the horn blew again signalling a start

to work. At 12.30 it sounded again for dinner and at 1 o'clock it again

signalled a start back to work. It echoed out again at 6 o'clock

to stop work for the day. The entire village used the horn as

their time guide. Times were hard for the workers. Bad batches of yarn

were the main reason for pay and argument. Some weavers blamed the `tenter'

for giving them a bad `beam'. On one occasion I remember quite clearly

my mother coming home with just sixpence in her pay bag. Pa McCandless

was the manager of the factory. He was feared and respected by most of

the workers, but was a fair man. When l started off in the `scrap

business' I operated between the gables of Thompson's Row and Puddledock

Row, what was in effect factory land. I worked here in the evenings

after having done my stint at Mackies in Belfast. Obviously someone must

have reported my making use of the land and I received a visit from Pa.

He arrived one evening and caught me at work, pointed out that I

shouldn't be carrying on my operations there and queried my working

hours. I told him I caught the 7.00 a.m. bus at the corner and arrived

home on the 6.00 p.m. at night. He commented on my hard graft and that

was the last I heard of the matter. Indeed a fair and just man who could

recognise a man's worth!

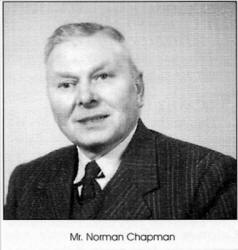

Norman Chapman was the engineer in the factory. He

was educated in the Public Elementary School and Lisburn Tech. A very

intelligent man, he read a lot and loved to engage in conversation with

anyone on any subject. Lizzie Chapman, Norman's mother, ran a small shop

at Smithy Row, beside the old oak tree which was near the factory gate

and which is still growing there. She was a very refined woman. Norman Chapman was the engineer in the factory. He

was educated in the Public Elementary School and Lisburn Tech. A very

intelligent man, he read a lot and loved to engage in conversation with

anyone on any subject. Lizzie Chapman, Norman's mother, ran a small shop

at Smithy Row, beside the old oak tree which was near the factory gate

and which is still growing there. She was a very refined woman.

When the Factory closed for good I, then owning a

scrapyard in the Old Railway Station, bought all the looms and machinery

in the factory and smashed them all up .for scrap metal and

removed them from the premises. A sad end for an old establishment, and

on recollection maybe the antiquity of the items outweighed the value of

the scrap metal!

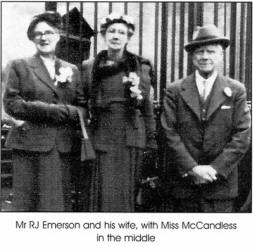

The Emerson family was well known in the village as

the owners of Culcavey Stores, the local shop. RJ Emerson (Rabbie John),

the head of the family, was assisted in the shop by his sister-in-law

Miss McCandless and his daughter Eileen. Miss McCandless was a proper

lady, very polite and mannerly. Eileen was also a lovely lady. Mrs

Emerson was a well thought of quiet lady, who ran the home. Bertie, the

son who looked after the .farm, provided the supplies of milk

in the village, for many years. In his youth he attended the

Agricultural College and one occasion when he was speaking on Radio

everyone in the village was listening in. Rabbie John was a well-known

man and was a Justice of the Peace. He also wrote many poems, some about

what was happening in the village. The Emerson family was well known in the village as

the owners of Culcavey Stores, the local shop. RJ Emerson (Rabbie John),

the head of the family, was assisted in the shop by his sister-in-law

Miss McCandless and his daughter Eileen. Miss McCandless was a proper

lady, very polite and mannerly. Eileen was also a lovely lady. Mrs

Emerson was a well thought of quiet lady, who ran the home. Bertie, the

son who looked after the .farm, provided the supplies of milk

in the village, for many years. In his youth he attended the

Agricultural College and one occasion when he was speaking on Radio

everyone in the village was listening in. Rabbie John was a well-known

man and was a Justice of the Peace. He also wrote many poems, some about

what was happening in the village.

The other members of the family were all well educated

and the village people were very proud of their achievements. Some were

doctors and one was a teacher The late Dr Douglas Emerson was one of the

most highly respected doctors in the country.

Another local shop was a small wooden hut built at

Culcavey crossroads by Harry Ginn. Harry was a real character who took a

great interest in council facilities and stood in elections. The hut

later became 'Thompson's wee shop', trading at the crossroads

for many years.

Back in the days of no supermarkets the people relied

heavily on the local shop. Other services were provided in different.

forms. Mr Bell was the dentist. He attended people in their own house or

in Miss Maggie Mercer's home. He came every Friday night with his small

bag. Another Mr Bell, 'Bomp Bomp' by nickname, was the shoemaker He made

shoes for some people and provided a mending service. Sammy Miller was

the vegetable man. Fish men came round shouting "Ardglass herrings ".

The village was visited weekly by two ice-cream men. Tommy Just from

Lisburn and an Italian man from Newry who came every Friday night and on

Sunday. Johnny Palmer came round with goods and oil and Billy Balmer

came round selling bread and pastry. The `pack men' came round the

village on a Friday night (pay night). Bobby McBride and a Mr Sharkie

came round with a suitcase full of new clothes. They had a lot of

customers. People got what they wanted from the suitcase or else they

ordered the item and they would get it the next week. They paid for

everything at a certain amount of money per week. Many a bride and

bridegroom were fitted out in this manner.

In all villages there was a local woman acting as

midwife. The midwifery service in Culcavey was the province of Mrs

Wilson, wife of Mr William Wilson, Snr. My recollection is that they

were from the South of Ireland. The doctor was only called to a

difficult birth, so Mrs Wilson acted as midwife to all the pregnant

women in the village. William Wilson was a big strong man who was always

working in his back yard where he kept goats and pigs. When Billy

Miller; the pig butcher was killing the pigs, the whole village could

hear the squeals before they were killed. Some people used to buy some

fresh liver for food.

If you were lucky to own a bicycle you would surely

need the services of Tommy Crothers. Tommy ran a small bicycle shop at

the quay which was' beside the canal at Newport. He repaired all the

cycles in the village. Renowned for a bit of good 'craic', he was known

to be fond of a bottle of stout. As none of the `working class' owned

cars many people had bicycles that were treasured as they provided the

means of travel the few miles or so to work. This meant there was' a

supply of second-hand parts from which many of the boys built 'an old

bike'.

Also residing clown beside the canal was Mrs

McGuiggan, the Newport woman who made banners and bannerettes for the

Orange Order. She was a member of Annahilt Presbyterian Church, and rode

on her bicycle to that church each Sunday.

For postal services there was Bob McAdam. Bob was

postman for many years and knew everyone in the district. He was a good

Lambeg drummer and followed the drums everywhere, and was a lifetime

member of Hillsborough Lodge 144. He also followed the local football

team and was a keen supporter of `The Blues' (Linfield).

The village people were always proud

of the men who fought in both World Wars.

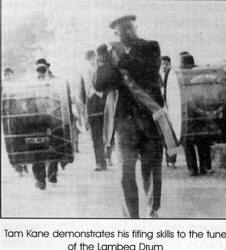

Tam Kane was a big man who soldiered in the First World War, and saw

service in the worst of the

fighting before being wounded and brought home. He became SDC of the `B

Specials' in Hillsborough � a post he held for years. The Kanes were a

military family. Bobbie and Eddie were two professional soldiers in the

Second World War. Bobbie was a Pipe Major and Eddie was mentioned in

despatches while fighting in Africa. Tam Kane was very fond

of playing in the card school on

the railway lines. When he got a winning hand he could be heard to

shout, `Come up to Brimmies', a place in France soldiers used to shout

about. Tom could also play the fife in tune

to the Lambeg drums. The village people were always proud

of the men who fought in both World Wars.

Tam Kane was a big man who soldiered in the First World War, and saw

service in the worst of the

fighting before being wounded and brought home. He became SDC of the `B

Specials' in Hillsborough � a post he held for years. The Kanes were a

military family. Bobbie and Eddie were two professional soldiers in the

Second World War. Bobbie was a Pipe Major and Eddie was mentioned in

despatches while fighting in Africa. Tam Kane was very fond

of playing in the card school on

the railway lines. When he got a winning hand he could be heard to

shout, `Come up to Brimmies', a place in France soldiers used to shout

about. Tom could also play the fife in tune

to the Lambeg drums.

Another villager who joined the Royal Navy before the

Second World

War was Peeler McAdam. On two occasions the ships

that he was on were torpedoed and sunk by the German U-boats. When he

returned home he got a great reception.

Jack Woodhouse was an English soldier who came to the

castle in Hillsborough. He married Bella Matchett, a Hillsborough girl,

and they settled in Culcavey. Jack had good community spirit. He got

involved in everything that took place in the village. He was MC in the

Saturday night dance in 'Ritchie's Hut' for many years. Ritchie's Hut

was the dance hall where many of the boys met girls, especially the

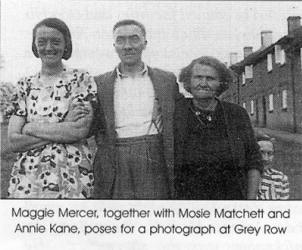

soldiers who were stationed in Hillsborough. Maggie Mercer, an unmarried

lady, who lived in the village all her life, was always called to sing

at the dances, her speciality being `Let him go and let him tarry'.

Maggie was known to everyone in the village, and took a keen interest in

the life and events of the area. Jack Woodhouse was an English soldier who came to the

castle in Hillsborough. He married Bella Matchett, a Hillsborough girl,

and they settled in Culcavey. Jack had good community spirit. He got

involved in everything that took place in the village. He was MC in the

Saturday night dance in 'Ritchie's Hut' for many years. Ritchie's Hut

was the dance hall where many of the boys met girls, especially the

soldiers who were stationed in Hillsborough. Maggie Mercer, an unmarried

lady, who lived in the village all her life, was always called to sing

at the dances, her speciality being `Let him go and let him tarry'.

Maggie was known to everyone in the village, and took a keen interest in

the life and events of the area.

Deeds and happenings were well talked of within the

close community of the village. One event I remember well was the act of

John McFarland. John's father was a Scotsman, who came down each

Saturday to collect his wages. While his father might have been

pecuniary John himself is remembered for rescuing John Singleton and Day

Patterson from drowning after they had fallen into the canal at Newport

Quay.

For this act he was awarded the Humane Medal. The

little ceremony awarding the medal took place on Newport Bridge,

officiated by Canon Mitchell of Eglantine Parish Church. This must have

been in 1938.

Many too will remember the acquisition of land by

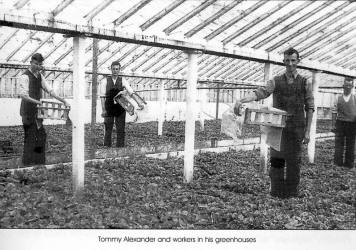

Tommy Alexander `Big' Tommy, as we knew him, was a man of good quality.

He bought a patch of ground that was covered with some of the oldest

trees in the land. To get this land cleared he gave the men of the

village one tree each. With spades, hatchets and crosscut saws they

cleaned the ground in six months. Tommy then turned the cleared area

into a very prosperous nursery. He employed some of the school children

after three o'clock to work at the lettuce and tomato plants,

and there was no shortage of labour Many too will remember the acquisition of land by

Tommy Alexander `Big' Tommy, as we knew him, was a man of good quality.

He bought a patch of ground that was covered with some of the oldest

trees in the land. To get this land cleared he gave the men of the

village one tree each. With spades, hatchets and crosscut saws they

cleaned the ground in six months. Tommy then turned the cleared area

into a very prosperous nursery. He employed some of the school children

after three o'clock to work at the lettuce and tomato plants,

and there was no shortage of labour

As you get older some names and faces become

memorable, sometimes for just small reasons, or perhaps it's

because you can relate events to these people. I remember Bob Armstrong

who rose each morning at 4.30 to 5.00 am. and rode his bicycle to

wherever his steam engine was working. His steam engine was used to make

the `copper' cam when Newport Bridge was built

after the old iron bridge collapsed. When I see hats I always think of

Bertie Carr: Bertie was a `bookies' clerk. He

lived at Railway Terrace and was always well dressed, wearing the best

kinds of hats in the village. As a very enthusiastic fisherman,

everybody wondered how he could catch so many fish. Again, I can see

today, as plain as if it was yesterday, Davy Finlay who lived between

Newport Bridge and the Moss Road. Davy kept a small shop and never

seemed to wash his face. The hens, ducks and guinea hens all lived in

the house along with the family. The door to the house was never shut.

The antics of three local farmers always brings a

smile to my face. Hubert Nelson, Charlie McBride and Wilson Verner met

every Saturday night in Nelson's pub in Smithfield Square, Lisburn. They

always got the 10.30 bus to Flatfield on the way home. Of course they

had plenty of money, but .for devilment they refused to pay

the conductor their fare. Some conductors knew how to handle them, but

others who didn't know were in trouble. However; the last man off the

bus usually had to pay! The antics of three local farmers always brings a

smile to my face. Hubert Nelson, Charlie McBride and Wilson Verner met

every Saturday night in Nelson's pub in Smithfield Square, Lisburn. They

always got the 10.30 bus to Flatfield on the way home. Of course they

had plenty of money, but .for devilment they refused to pay

the conductor their fare. Some conductors knew how to handle them, but

others who didn't know were in trouble. However; the last man off the

bus usually had to pay!

At the other end of the scale I remember the refined

Mrs Pimm who lived in a large house at the top of the factory hill. She

was a lady who kept herself to herself and was seldom seen in the

village. However the villagers showed her great respect.

Few people could not remember Hugh Ball. Hugh married

Maggie Cargin and came to the village to live. His great passion for

hunting rabbits was well known throughout the country. Hugh kept an

excellent dog for hunting called Queenie. He also reared some of the

best ferrets in Ireland. Hugh started work in Hillsborough Forest when

he was thirteen. He never went to school and could not read or write. As

a Forestry employee he was horseman and gamekeeper, and was awarded the

Imperial Service Medal, which was presented to him at Hillsborough

Castle. He apparently never took a holiday, but preferred to go in to

attend the horses or go hunting in the forest with his ferrets and dog. Few people could not remember Hugh Ball. Hugh married

Maggie Cargin and came to the village to live. His great passion for

hunting rabbits was well known throughout the country. Hugh kept an

excellent dog for hunting called Queenie. He also reared some of the

best ferrets in Ireland. Hugh started work in Hillsborough Forest when

he was thirteen. He never went to school and could not read or write. As

a Forestry employee he was horseman and gamekeeper, and was awarded the

Imperial Service Medal, which was presented to him at Hillsborough

Castle. He apparently never took a holiday, but preferred to go in to

attend the horses or go hunting in the forest with his ferrets and dog.

One of the most important sports during the 1930's

and 40's was football, and Culcavey always had a good team. They played

under the naine `Distillery', which came from the old distillery that

had been in the village before the advent of the linen factory.

Competition was very strong as all the local towns and villages had

teams, and of course there were star players. To name but a few: Albert

Pollock; the Wilsons; the McDonalds, Johnstone, Cairns and `Head,

heel toe' Sammy Atcheson. To think of Sammy is always to think of

football. He was a very lively man and was a really good centre forward

for the local team. Everyone used to hear him shout `Head, heel or toe,

let her go'. On one occasion he won a considerable amount of money on

the football pools, and this was the talk of the village. Sammy became a

born-again Christian, and .for many years he preached in

Lisburn Square on a Saturday night in front of a

good crowd of people. He paid visits to all the sick people in local

hospitals. One of the most important sports during the 1930's

and 40's was football, and Culcavey always had a good team. They played

under the naine `Distillery', which came from the old distillery that

had been in the village before the advent of the linen factory.

Competition was very strong as all the local towns and villages had

teams, and of course there were star players. To name but a few: Albert

Pollock; the Wilsons; the McDonalds, Johnstone, Cairns and `Head,

heel toe' Sammy Atcheson. To think of Sammy is always to think of

football. He was a very lively man and was a really good centre forward

for the local team. Everyone used to hear him shout `Head, heel or toe,

let her go'. On one occasion he won a considerable amount of money on

the football pools, and this was the talk of the village. Sammy became a

born-again Christian, and .for many years he preached in

Lisburn Square on a Saturday night in front of a

good crowd of people. He paid visits to all the sick people in local

hospitals.

Other sporting diversions also occupied much

appreciated spare time. A game that was played in the early party of the

century was called `bowls', not the sane as a game of `bowls' played

today. A group of men gathered at a point on the road. Another point on

another road was picked. In turn they `hinched' a stone called a

`bullet', The person who covered the distance between the two points

with the least number of throws was the winner

Skittles were also played. A circle 2 feet 6 inches

in diameter was drawn on a level part of the road. It was divided into

four quarters. A skittle was stood on end in the centre of the circle

and one stood on end on each of the four quarters. A player stood at the

butts, which was some distance from the circle. He had three skittles

which he threw at the circle, one at a time. The idea was to knock the

other five skittles out of the circle. The number of skittles

knocked out of the circle decided the winner. This game went on for

hours. Skittles were usually cut about 12 inches long from an ash tree.

The younger boys of the village had games of their

own to play. A race up the front of the houses and down the back with

`hoops and cleaques' by a dozen or more boys made a terrible

noise. They also played `Hunt the deer', Blind man's

buff' and `Hide and Seek'.

`Chestnuts' was a seasonal game. "Are you coming for

a game of cheesers?" was the usual question. We gathered chestnuts in

the glen, Harry's Road, Aughnatrisk Road, and the `Plantin'.

Although `Chestnuts' is a very old game, the generations of today still

know how to play it.

WORKING WITH MY FATHER

Thomas Palmer, a well-known local businessman from the Halftown area,

recalls his experiences.

I believe I was seven years old when 1 was first allowed

to go out on the van with my father � a special birthday treat. At the

time we were living in the old railway station at Hillsborough, the shop

and the pumps at Spruce field having been vested by the government

.for the construction of the Ml Motorway. For a delivery vehicle

we had a green Commer 15 cwt van and there was not much room, even for a

small boy, given the range of items packed into the van. I believe I was seven years old when 1 was first allowed

to go out on the van with my father � a special birthday treat. At the

time we were living in the old railway station at Hillsborough, the shop

and the pumps at Spruce field having been vested by the government

.for the construction of the Ml Motorway. For a delivery vehicle

we had a green Commer 15 cwt van and there was not much room, even for a

small boy, given the range of items packed into the van.

I did not have a proper seat as such � I had to lie

on a coat, which was put on top of the potatoes. The potatoes were

weighed and put on the van in full-size metal biscuit tins � when

customers bought a stone of potatoes they emptied them into a box and

gave us back the tin. In addition, �

stone (71b) of potatoes were sold in brown paper bags � plastic bags

were a much later invention. Blues were the main eating potato at that

time and very few whites were sold. Similarly, white eggs

were generally the only eggs available � compare that to today where

white potatoes and brown eggs especially, dominate the market place.

On school holidays it was the done thing that either

myself or my brother, or one of my sisters, went on the van with my

father to give him a hand. When the weather was good it was pleasant and

interesting, especially going into farmyards, lifting produce and

getting the odd ride on a tractor; be it with Kennedy Hunter or Billy

McCoy. Going around the estates meant that you got to know a large

number of people and saw a wider picture of life.

Some house calls were special, where you would be

given a cup of tea, a biscuit, or in some cases a cup of lemonade, and

the use of a toilet. There were various points around the country where

you could stop and have something to eat, e.g. at Smith Lane en route

from Culcavey, but before hitting Coronation Gardens. During the winter

we would have a flask of soup and sandwiches, but in the summer it would

be lemonade, sandwiches and biscuits.

Various world events also happened when I would be on

the van with my father I remember us being at Lily Porter's house in

Coronation Gardens when Thompson Crossey came over to the van and

announced that Kennedy had been shot. I didn't real/v know who Kennedy

was then, but like most other people, I now know where I was when

Kennedy was shot. Another important event was van walking on the moon,

and we were making our usual Saturday call at Maria McGuriiaghan's

on the Blaris Road when Gerald McConville came out to the van and said I

should come in and see man walking on the moon tar the first time. The

house had no electric at the time, but Gerald had a TV that worked off a

car battery. He would leave it round to the shop, strapped to the

carrier on the back of his bike, to get it charged and we would leave it

back on a Saturday during our delivery. Gerald had recognised that this

was a unique event in world history and he ensured I was able to witness

it. Incidentally, there was also a very large horse drawn cart in Maria's

barn, which I would look at every Saturday, thinking what it had been

used for and when it was last used. Given the moral upbringings of the

time, the rule was that small boys were seen and not heard and I have

yet to find an answer to my questions.

|