|

MEMORIES OF THE WAR YEARS AT HALFTOWN

Harold McBride, born and brought up at Demiville, paints a picture of

life in the Halftown during the war years:

My first memories of Long Kesh was attending auctions

of farms on the Halftown and Bog Roads. My father bought two cows and

several chicken coops at the late Johnny Palmer's auction. The farms

were taken and the residents displaced to build the aerodrome. They also

took 4 acres from my father's farm at Demiville to build a

communications centre. This building was placed close to the farm so

that any German bombers attacking Long Kesh might be confused. The

blast-proof walls were 3 ft. thick and the building had no windows. Army

VIP's used to stay in it, so it was always under heavy guard,

with the guards making us show our identity cards each time we passed up

or down our avenue!

Many aeroplanes crashed on the farm during the war,

sadly sometimes killing the pilot or flight crew, some of which are

buried in Eglantine Parish Church graveyard. One 'plane

crashed in one of our cornfields while my father and the farm workers

were busy harvesting. No crew were killed but the 10 acre field of grain

was destroyed, mainly by locals coming to view the crashed 'plane!

When the 'plane was coming down it passed so low over the

harvester that it blew my father's hat off.

Another crash occurred on the Halftown Road close to

the Blaris Road junction, and as a result the road was closed to traffic

for several days. However, each morning and afternoon a policeman

carried myself and other children under the .fuselage so that

we could get to Newport School, this was in May 1943.

The fields and farmyard at Demiville were often used

by troops, including Americans, for war manoeuvres, and it was not

unusual to wake up and find hundreds of tanks and guns surrounding the

farmhouse. The soldiers often used the hay barns and farm buildings to

sleep in and it was a constant worry to my father that a careless

cigarette butt might burn our total winters cattle fodder! My mother

used to make huge pots of broth and serve it to our khaki clad visitors.

Problems were sometimes caused by the army leaving

gates open and allowing cattle or the farm horses to stray. Quite often

the hungry soldiers raided the hen houses for eggs or the greenhouses

for tomatoes! Once, just prior to Christmas, my father caught some

Americans raiding our turkey flock. A telephone call to the Commanding

Officer at Long Kesh led to apologies and compensation.

On one occasion my father was delivering a lorry load

of hay to a funeral undertaker in Dromore - no doubt to feed his several

carriage horses. Shouting was heard from the back of the lorry, and on

investigation 3 soldiers were found - they had been sleeping in the hay

on the pre-loaded lorry and were surprised to find themselves in

Dromore!

During the war years friends and distant relations

from England would contact us with names of people stationed at Long

Kesh. It was usual for my parents to invite these soldiers to Demiville

for meals and a hot bath. Often these evening would end in a sing song

with my sisters Elsie and Edna playing the piano.

In 1943 my elder sister Edna married Lieutenant Alan

Chapman of the Royal Engineers, one of the many soldiers that were

invited to Demiville, and indeed quite a few Halftown girls married

soldiers who had been stationed at Long Kesh.

THE GAMES WE PLAYED

Years ago most games were played outdoors as there

were no televisions, videos, computers or playstations. Some games were

only associated with girls while others were classed as boys' games, but

a few existed where boys and girls could play together. Team games began

by the two leaders picking a person each to play on their side, and this

continued until everyone was chosen. The tallest one always got picked

first if height was useful in a game, and if speed was the essential

essence of a game then the fastest runner was always picked. Usually the

smallest person involved in the game was picked last.

BALL GAMES

Ball games were played mostly by girls, the boys usually playing

football. The games were played using either one ball (a tennis ball or

rubber ball), two balls, or three balls. The balls were bounced against

a wall (usually a gable wall), and you clapped your hands before the

ball was caught on the rebound. The number of balls used depended on the

skill acquired. One ball was easy, two more difficult, and using three

meant you were 'a dab hand'. This would be done until they counted ten.

If you dropped a ball, then you started all over again. Many rhymes were

used when playing ball.

QUEENIE, QUEENIE

Another game played by girls was called 'Queenie, Queenie, who has got

the ball?'. One person with a ball would stand with their back to a

group, and would throw the ball over their shoulder. The person who

caught the ball would hold the ball behind their back, while the others

would also stand with their hands behind their backs. The group would

call out 'Queenie, Queenie, who has got the ball? The

person who threw the ball would turn round and try

and guess who had the ball. If they guessed right then the person who

had caught the ball would take their place and would throw it. If they

guessed incorrectly then they had to turn their back and start again.

MARLIES

Marlies (marbles) was a boys' game. Older marlies were made of stone and

called 'stonies', chalk marlies were 'chalkies' and in the mid-thirties

glass marlies were made and they were known as 'glassies'. Chalkies

disappeared when glassies became popular. Marlies were played on the

ground. When you hit the other fellow's marlie you kept it or if he hit

your marlie he kept yours.

KITES

Nobody bought kites years ago, they were home-made, usually by an adult.

They consisted of two strips of wood placed on top of one another to

form a cross and tied securely where they crossed in the middle. A piece

of strong thread or thin cord was tied round each strip and so formed a

square or rectangle. The frame was then covered with an old newspaper.

Tails for the kite were made with strips of paper about 3 inches square

and folded three or four times and then twisted in the middle like a

propeller. The tails were tied in a long line about two inches apart. A

ball of twine was the best to fly the kite with. Flying kites was

usually associated with the autumn when the weather turned windy.

O'GRADY SAYS

Both boys and girls played this game. The players formed a long straight

line, while the leader shouted commands. Each command had to be preceded

by the order 'O'Grady says', for example 'O'Grady says clap your hands',

and the players clapped their hands. But if the order was `clap your

hands' and you did so, then you were out, because O'Grady hadn't ordered

it. When the orders came thick and fast it was hard to remember whether

O'Grady had given the order. Boys who were in organisations such as the

Boys' Brigade, Life Boys, Church Lads' Brigade or Boy Scouts were hard

to catch out as they played this game as part of their training.

GUIDERS

Guiders were built at home, usually using pram wheels or ballbearing

wheels. Guider races were quite competitive and a good pusher was

essential as he pushed as fast as he could and then hopped on the back

going down a hill.

PEERIE AND WHIP

This game was played with a small wooden spinning top, about three

inches long, round in shape and sloping to a point with a steel tip to

make it spin on the ground. The peerie was kept spinning by hitting it

with a little whip. Boys and girls could spend hours trying to keep the

peerie spinning as long as possible.

Many people will also remember playing Tig, Rounders,

Hopscotch, and Skipping, to name a few. Innocent, enthusiastic games

played an era ago.

AN INTRIGUING STORY

THE CLUE OF THE FOUR

SOLDIERS

SAM HANNA BELL

For over two hundred and fify years horse-racing has been held at the

Maze, on the level floor of the Lagan Valley, near Lisburn. "Race Week

at the Maze" says an old record, "was as much a fair as a meeting and

drew immense numbers of people." The gentry were there, and the strong

farmers; the weavers from the valley, the tradesmen, the vendors of

pies, crubeens and dulse; the ballad-singers, trick-o'-the-loop men,

apprentices, farriers, and many other assorted characters, honest or

shady. And of course, there were present in this great hiving concourse,

the jockeys and horse-dealers. Later in the afternoon of Saturday, July

24, 1813, after the last race of the day, three men, one of them leading

a grey with a switch tail and a cut above the eye, left the still

crowded noisy course and took the road to Hillsborough.

THE MUSICAL TRAMP

The three were Owen McAdam, a horse-dealer of about 28 or 30 years, from

Keady in county Armagh, Bernard McCann, a journeyman baker, aged 26,

employed by Mr Adam Sloan of Lisburn, and a seedy-looking itinerant,

Toby Boyce by name, of indefinite age and occupation. Three very

ordinary individuals, you may say, of no more significance than any of

the other hundreds of the great crowds now drifting away from the Maze

on that July evening. But in the light of the strange and tragic

occurrence that took place in the next twenty-four hours, the movements

of the three wayfarers were to be as carefully uncovered and

investigated as lay in the power of the law in those days.

Reaching Hillsborough they stopped at an eating-house

owned by Mrs. Frances Murdie, where McAdam ordered dinner and asked

permission to stable the grey horse with the switch tail until he was

ready to leave. The three travellers drank freely for a time. McCann

then declared he could eat a dinner but refused to have Toby Boyce in

his company. Not even a jig on the tin whistle by the tramp, who was a

skilled performer, soothed the baker's breast. Blows were struck and

McCann ordered Boyce to clear out. When the tramp claimed Owen McAdam's

friendship the baker was about to set on him again when McAdam,

according to Mrs Murdie, told McCann to "keep his fists in his pockets

or they would get him into trouble".

The tramp, realising that present company held no

profitable future for him that evening, declared he would return to

Lisburn. The young horse-dealer gave him a florin and Boyce decided that

he could still catch the Hillsborough carrier on its way to the

neighbouring town. As they were checking the time, McAdam produced a

watch. The sharp eyes of Toby Boyce noted the figures of four soldiers

engraved on the dial and on admiring the "purty timepiece" he was

informed by McAdam that "there wasn't a watch like it in Ireland". Then

the tramp, after showering his blessings on McAdam and, cursing McCann

for robbing him of a dinner, left the eating-house. More liquor was

ordered by McCann and in the course of their drinking they tossed to

decide who would pay for the dinner. McAdam won and on his being

challenged by McCann that he couldn't have footed the bill anyway, the

horse-dealer produced the result of his week's dealing, a roll of nearly

�70. The baker then refused to accept the toss of the coin and Mrs

Murdie remembered McAdam asking her, "Is it fair, that when we gambled

for our dinner, I should be asked to pay for it?" Whereupon she replied

that it was no concern of hers, so long as one of them paid. The

horse-dealer and the baker then settled down amicably enough to their

meal and liquor, and afterwards, when they had retrieved the grey horse,

they left Mrs Murdie's premises.

THE DARK NIGHT ROAD

Their next call was at the house of John Chambers, a Hillsborough

horse-jobber. There Chambers and McAdam agreed on a price of fifteen

guineas for the grey, but Chambers had only five guineas in the house,

which he wanted McAdam to take, promising him the balance of the money

at the next Dromore horse fair. McAdam wouldn't agree to this, although

as Chambers was later to testify, he was very much urged to do so by the

baker. At seven o'clock they were in James Rooney's public

house at Blaris. There they drank a naggin of spirits

together. They left shortly after, and went towards Lisburn. Later that

evening they returned and knocked Rooney up and got out to the door

half-a-pint of spirits, a small part of which the baker drank and then

filled a glass for McAdam, and when this was finished pressed a second

glass on him. When Rooney protested that McAdam had taken much more than

was good for him, McCann answered that he would "sober up this Keady

man". About ten-thirty that evening the two men and the horse set off in

the dusk towards Lisburn.

WHAT THE MORNING REVEALED

At eight o'clock the following morning, Sunday, John Walker of

Culcavey, saw the body of a man in the canal at Newport Bridge, near

Lisburn. He drew it from the water and sent for Sir George Atkinson, the

noted physician, who lived nearby. There was a deep cut in the back of

the victim's head as if he had been struck with a stick or the butt of a

whip. The neck was much blackened and torn and when Sir George pressed

the corpse's throat much blood issued from the mouth and nostrils. The

dead man's jacket had been dragged down from his shoulders to the

elbows. Sir George gave it as his opinion that the dead man had been

stunned then strangled, before being thrown into the water. The pockets

were empty apart from a button mould and a piece of ginger. During the

inquest the murdered man remained nameless for no one could identify

him. So the body was placed in an open coffin and exposed in Lisburn

churchyard in the hope that someone would recognise the victim. And in

due course someone did. Toby Boyce shuffled up to the railings, took one

look, and declared: "It's Ownie McAdam, Ownie McAdam from Keady. I knew

him well, sir. God rest him, he was as dacent a young fella as ever

stepped. And I can tell ye who murthered him � `twas Barney McCann �

that's the one ye want to catch."

But the baker had disappeared. The last news of him

came from William Mills, proprietor of the Red Cow Inn on the Lurgan

Road, who gave evidence at the inquest:

|

Mills: |

At five o'clock on the morning of Sunday, 25th,

a man rapped me up and asked for breakfast. He wore a

light-coloured fustian jacket and britches, white stockings and

buckles on the side of his shoes. |

|

Coroner: |

Did you serve him breakfast? |

|

Mills: |

I did. When he came to pay, he offered me a

horse he led, for a guinea and the price of his breakfast. |

|

Coroner: |

Did you observe the horse? |

|

Mills: |

I did. It was a grey horse, about two years

old, rising three, with a bite over the left eye and a switch

tail. |

|

Coroner: |

But you did not take his offer? |

| Mills: |

No, sir. |

| Coroner: |

As a matter of interest, Mr. Mills, why not?

Was not such a horse for a guinea a cheap bargain? |

| Mills: |

Too cheap. Too cheap by far. |

|

Coroner: |

Then you suspected something odd about this

fellow? |

|

Mills: |

Nothing that would have made me suspect him as

a murderer. He looked a cool, crafty character. The idea might

have crossed my mind that he came by the animal none too

honestly. But as you, sir, and the gentlemen of the jury well

know, the Maze Races brings many villainous fellows from all

arts and parts. The wise man shows no curiosity in them. |

| Coroner: |

And after he had breakfasted? |

|

Mills: |

Paid his bill, caught his horse, and rode off

in the direction of the Armagh Road. |

The jury brought in a verdict of Wilful Murder

against Bernard McCann for whom immediate search was made, but the baker

in the fustian jacket and white stockings, riding the grey with the

switch tail, had vanished as completely as if the turnpike road to

Armagh had opened and swallowed him and his mount.

THE FOUR SOLDIERS APPEAR AGAIN

That is, until one night, ten years later, when there occurred one of

the most remarkable coincidences in Irish criminal history. The

fortuitous encounter between two men took place in a tavern in Galway

City. One was the wandering Toby Boyce, still on the roads, with his tin

whistle, and the other a prominent citizen of that western town. Boyce,

it appears, had been summoned from the street by two or three

merrymakers desirous of having a tune with their liquor. Late in the

evening the tavern-keeper refused to serve any more drink "as the clock

had gone twelve midnight and tomorrow was the horse-fair". Several of

the drinkers challenged this ruling and appealed to a quiet,

respectable-looking citizen, a Mr. Hughes, to confirm that the landlord

was mistaken. But Mr. Hughes agreed with the landlord and good-naturedly

drew his watch from his fob in proof. Toby Boyce, on the fringe of the

group, noted with bulging eyes that engraved on the face of the watch

were the figures of four soldiers.

We do not know how the ragged vagrant managed to

convince the Mayor of Galway that James Hughes was not what he seemed to

be. Hughes had married into one of the most prosperous shop-keeping

families in the town and he and his wife had now a family of four

children. He had built up a thriving butchery business and was

considered by his neighbours to be a solid and respectable citizen. Some

remembered his arrival in Galway eight or ten years previously and had a

vague idea that he came from Dublin or the midlands. Certainly he had

never given them the impression that he came from the North, nor, for

that matter, had he ever found need to deny it.

THE FATAL SLIP

The arrest of Hughes (or McCann) created a sensation in Galway. But

after he had been apprehended the accused made several significant

denials and admissions. He denied that he had ever gone by the name

McCann or that he had ever been in Newtownhamilton, McCann's birthplace.

He admitted to Mr. Burke, Mayor of Galway, that he came from the north

and was born within a mile-and-a-half of Dungannon. Then, in

conversation with Burke, he made a fatal slip. "How can they prove that

the dead man who was drunk, didn't fall into the water and get drowned?"

"At that", said Mr. Burke, "I turned away from him. To my knowledge no

one had mentioned the circumstances of McAdam's death to the prisoner."

So, on the 18th June 1923, the accused man was

brought North. In Lisburn courthouse he was questioned by Mr Hugh

Robinson JP on his claim that he was born near Dungannon. Also present

was the Hon and Rev Edmund Knox, Dean of Down, who had lived for many

years in this part of Tyrone. Although he maintained his composure it

was evident that the merchant from Galway was hard put to it at times to

answer the dean's questions. Mr. Robinson brought the examination to an

end: "Bernard McCann, I am not satisfied with your answers, and,

therefore, as magistrate of this county, I return you for trial at the

Assizes to be held in Downpatrick, where you will be indicted for the

murder of Owen McAdam."

The trial was minute and lengthy. Prosecution and

defence brought witnesses from Galway and Newtownhamilton, and from

Hillsborough came Rooney the publican and John Chambers, the jobber in

cows and horses, who recalled the evening on which McAdam and McCann had

called with him, but under cross-examination would not swear that the

man in the dock was McCann. Also unhelpful to the prosecution was the

behaviour in the witness stand of Toby Boyce, the itinerant musician who

played such a strange part in bringing the accused man to trial. It did

not greatly impress the learned judge or the jury. "Of course it's him!

Of course it's Barney McCann! Forget those eyes wid the murder peepin'

out o'them? Ho, ho, ye damned ruffian. You're in the right place now!

The rope's been in the making for ye this past ten years."

| Mr. Hickey: |

I object. This is completely irrelevant! |

| Judge Moore: |

Remove this man from the witness box. |

A Mrs Alice Spears, from Newtownhamilton, the

murdered man's sister-in-law, then testified that the watch had been in

the McAdam family for generations and that it was she who gave it to

young Owen on the death of her husband. Mr Burke, Mayor of Galway, told

the court that the watch with the four soldiers on it had been found on

the accused man at the time of his arrest. He declared that he had known

the accused for twelve or thirteen years. He was then cross-examined by

Mr. O'Mally for the prosecution. Also from Galway came Mr. Thomas Ellis,

a shoemaker. He declared that he had known the accused for twelve or

thirteen years. He was then cross-examined by Mr. O'Malley for the

prosecution:

|

O'Malley:

|

You say you've known the accused twelve or

thirteen years. Are you sure it's not ten years? |

|

Ellis: .

|

I'm sure of twelve or thirteen. I made shoes

for Mr. Hughes and his family all that time |

|

O'Malley:

|

You have a very clear memory, Ellis. How can

you be so positive. |

|

Ellis:

|

Another cobbler in Galway owed me 30 shillings

for wages just about the time Mr. Hughes came to Galway. I made

out a bill for the 30 shillings and he hasn't paid me yet. |

| O'Malley: |

And you still remember that 30shillings. |

| Ellis: |

I'll never forget it. |

The prosecution, with greater success, called several

witnesses who swore that the prisoner, Bernard McCann, otherwise James

Hughes, was one and the same man and had lived in Newtownhamilton until

his departure ten years before.

| O'Malley: |

You say you recognise the accused as Bernard McCann of Newtownhamilton? |

|

Preston:

|

Oh, certainly. Certainly, that's him. His hair

has changed a bit after ten years and he's got a bit lustier.

But that's Barney McCann. That's him all right. |

Following the conclusion of the evidence, Mr. Justice

Moore summed up and the jury retired to consider their verdict. Within

the hour they returned with a verdict of Guilty.

|

Judge: |

And that is the verdict of you all? |

|

Foreman: |

Yes, my lord. And in view of the subsequent

good conduct of the prisoner, we would recommend him to mercy. |

|

Judge: |

Under the circumstances of the case your

recommendation can have no effect. |

McCann, throughout the trial, had behaved with a

calmness amounting almost to indifference. He now mounted to the dock,

firmly and steadily, to hear his fate. Only once did he interrupt to

declare his innocence, whereupon Judge Moore admonished him: "Do not, by

denial, make your condition more miserable than it is. Do not further

taunt your God by appeals of your innocence. Do not, I beseech you,

lay the flattering and dangerous unction to your soul that there is a

shadow of hope that the sentence of the law will not be carried into

effect. Little now remains of my painful duty but to pass upon you,

Bernard McCann, the awful sentence of the law. You shall be removed from

where you stand, to the place from whence you came, the common gaol,

there heavily ironed, until the day of your execution. You shall then

have your irons struck off and be taken to the place where criminals are

usually executed and there hanged by the neck until you are dead. And

may the Eternal and Omnipotent God have mercy on your soul."

On the appointed hour Bernard McCann paid for his

crime. Of what happened to his wife and four little children there is no

record. And what of the fateful timepiece with the four soldiers that

led to his apprehension? Perhaps it is lying today in some drawer or

box, dusty and unwound, having told the duration of a man's lifetime.

POETS' CORNER

For the hardworking people of the Culcavey/Halftown

area, there may have seemed little leisure time. But for some, any free

time could be spent in recollection and the transmission of their

thought into words. The finely tuned words, the evocative phrase was

often about their surroundings and their lives. As we read these words

we can feel their pride of belief and surroundings, and the pleasure and

meaning of the message they impart.

THE BABE OF BETHLEHEM

By Rabbie John Emerson

Rejoice, ye people, all rejoice,

And let the joy bells ring;

United join with heart and voice

To hail the newborn king.

And what a humble, lowly birth

His life work to begin;

No sign of welcome or of mirth,

No room in Bethlehem's inn.

But, lo! A heavenly star so bright

Shone o'er where he was laid.

And shepherds wondering at the sign

Were troubled and afraid.

Those men who knew the eastern sky,

Their starry hosts of night,

Behold the scene with wondering eye

An unfamiliar sight.

And ministering angels overhead

Acclaimed Him for the sky,

While hovering o'er that manger bed

Brought homage from on high.

Rejoice, yea, people all rejoice,

And let the joy bell ring;

United join with heart and voice

To serve the newborn king.

RJ Emerson composed many poems and was given the title

of `The Culcavey Poet' by the Dromore Leader.

ALL SAINTS

By Bertie Emerson

On the Eglantine Estate

In the quiet countryside

Miss Mary Mulholland chose a site

For a private chapel � English style.

Amid the verdant pastures

There's an edifice in stone,

And yew trees stand sentinel

On lawns that are well mown.

With nature's beauty all around

It would be very hard to find

A nicer place wherein to worship

Than in All Saints Eglantine.

THE GOVERNOR

By Bertie Emerson

There's a beautiful spot in County Down

Where the Governor lives in our little town.

Governors come and Governors go

They don't go on forever you know!

Lord Wakehurst retired, Lord Erskine came

Tradition was broken, though our laws are the same.

There were many people who thought it not right

That official persuasion should change overnight.

Presbyterians, of course, took a different view,

So red carpet appeared in the Governor's pew.

Lord Erskine, being of Scottish descent,

When Sunday came round to the meeting house went.

There in surroundings, so sturdy and plain,

He heard the old message expounded again.

The Benediction pronounced, church members depart

With true Christian fervour renewed in their heart.

Lord Erskine of Rerrick was Governor of Northern Ireland

from 1964 to 1968 and was the only Presbyterian to hold this office.

OUR TOWN

By Bertie Emerson

There's asphalt now on my cobbled streets,

The rubber tyre replaces the horses feet:

But the wind still whispers through the trees,

If you care to listen, it's bound to please.

Natural beauty there's in plentious store,

From the garden gate to your own front door.

In this lunar-computer age of man,

They gave me no place in the Matthew Plan.

The Stormont planners passed me be,

I study the plan, and I wonder why.

Perhaps they think that I'm much too small,

Or, maybe, don't realise I exist at all.

When the Assembly Clock rings the mid-day hour,

You have hardly room to park your car;

There are one-way streets and yellow lines

And dozens and dozens of traffic signs;

KEEP LEFT � LOOK RIGHT � NO PARKING HERE,

Do not enter the BOX unless your exit is clear.

There are motor cars and limousines,

Electric cookers and washing machines;

Schools for girls and schools for boys,

Terrific displays of children's toys;

Well-dressed women in tailored suits;

Long-haired males in Beatle boots.

A shortie coat for the young man-about-town,

It's fur-lined suede, and it's probably brown.

The women go shopping in skirts and tights,

Some of those in slacks look ghastly sights.

Take a free gift � 3d off � advertisers' bluff,

You've got to pay if you want the stuff.

Now here's a treat for your wife and you,

Move your home, get one with a view,

Plus central heating of so many therms,

If you can't pay cash try our easy terms.

What! You can't face the bill, no need to moan,

Pop round to the bank for a personal loan.

They are mixing meal and baking bread,

Weaving cloth and making thread;

Demolishing slums and building homes,

Constructing roads, installing `phones,

Modernising the hospital, enlarging a school,

Choosing a site for a swimming pool.

A varied selection of outdoor sports,

With playing fields and tennis courts;

A cricket pitch and a bowling green,

And the best of golfers that ever were seen;

There are pigeon fanciers and football fans,

Lambeg drummers, accordion and kiltie bands.

The adults work and the children play,

And before you know it's the end of the day,

When the teenage youth, the fathers and sons,

Will return to their home where life begun,

To enjoy the food, the love and the care,

Lavished by mother on everyone there.

The Lisburn Herald published the above on 4th November

1966

LISBURN

By W Pearson junior

The Twelfth Mom it was bright and clear,

There was balm in the scented air

With the strains of triumphant music

That would banish all your care.

The historic town of Lisburn

Saw once more an Orange throng

Swell within her streets and rural lanes

As the brethren marched along.

And the crowds that lined the streets that day

Were amazed at that vast array,

For never was a demonstration seen

As they beheld that day.

With banners shimmering in the breeze,

They marched beneath their fold,

In memory of King William �

Our deliverer so bold.

LOL One-Hundred-and-Eleven led the district,

As soldiers to the fray.

There never was a prouder lodge

Than they turned out that day.

The Lisburn Temperance Silver Band

Led them martially to the "field" �

A band of Protestant brethren

Whose hearts shall never yield.

We think of our absent Brethren who sleep in peace

With kindred ashes of the noble and the true.

Hearts that never failed their country �

Hearts that baseness never knew.

May they rest until the trumpet

Wakes the dead from earth and sea;

England shall not boast of braver sons,

Than they, who died to set her free.

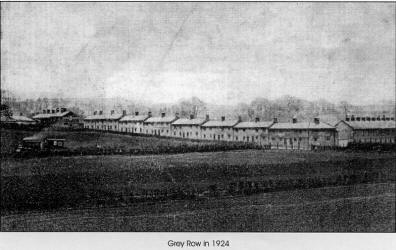

GREY ROW

By Thompson Crossey

As I stood on the hillside and watched your demise

My mind wondered back through the years.

To a time when people who lived `neath your roof,

Had worried but not many fears.

I remember the people who stood at the door

And watched everything that went on.

They would then talk about something special they'd seen

That was something they all had in common.

I remember the happenings that took place through the

years.

The sunshine, the laughter, the joy.

The winters, the rain, the snow and the ice,

And the birth of a girl or a boy.

I remember the names of the people

Who lived side by side through the years.

People who shared what little they had,

Their food, their laughter, their tears.

The characters too, I will never forget.

For their antics and folklore will live

In some of the men and the boys now passed on

There was plenty of folklore to give.

The lassies too were a lively bunch.

They could run and skip and dance.

But along came some strangers as strangers do,

Then some girls were lost to romance.

There was Tissie and Rose, Lily and Nell

Madge, Maud and Harriet and Ria as well

They were all lovely lassies, all full of fun,

All proud of the place where their lives had begun.

When it came to good crack

One thing you would find

They could all hold their own,

The girls weren't behind.

The boys used to stand at the corner

They stood there day in and day out

The stories they told were both brave and bold,

And some were even quite stout.

Skittles was one of the games that they played,

They played at the cross of the roads.

When a Klexton horn blew the players all knew

It was time for the crowd to explode.

Sunday was special to some of the boys

But to church they never did go.

They headed up the road and into a shed,

And all sat down in a row.

They would bring out the cards that were well worn

with age,

And there, they'd play for hours at a time.

Until someone would shout `the peelers are here',

Then they'd all disappear down the line.

Bob Wilson would whistle a tune loud and clear

The sound could be heard o'er the land.

He played football as well and drummed the big drum,

He was also in Lisburn's pipe band.

There was Packy and Atchie, the Chit and the Chew

There was Davy McFarland, who everyone knew.

Sam Ginn was a big man as tough as could be,

When he offered to fight, the boys would all flee.

Of course there is always one person

In every village or town

Whose name will be always remembered

Because he's a man of renown.

Robert John Emerson is the man I recall

A man who could view the whole street.

He had done so for years, in fact all his life,

His shop was where people did meet.

They told him their stories of trouble and strife,

Of all the good happenings as well.

Although he heard things, that could cause concern,

Not a word did Rabbie John tell.

He was known for his poems, he penned through the

years,

He was also a J.P. as well.

When Rabbie John died, his loss was great,

But his story I'm quite pleased to tell.

I could sit here for hours and mention the names,

Of all the good people who've gone.

I have mentioned a few, but others I knew

I will never forget even one.

In your demise, Old Grey Row

We will always remember your being.

We thank you for all the pleasures you've left,

And of course we were sad at your going.

So `Old Grey Row' or Hillside Terrace

As you were christened in later years,

Many who stood and watched your demise

Did so with eyes full of tears.

THE GLEN

By Thompson Crossey

Come and take a walk with me

Those of you who will.

We'll start up here at McBride's old dam

And we'll dander down the hill.

We'll walk beneath the canopy

Where the beech and oak entwine,

Where rooks and crows have lived for years,

And bred right down the line.

We'll pay a visit to the glen

Where the boretree and the bluebell smell,

Where the sprick, the caddis and the leech

In the running river, all do dwell.

We'll stroll down past the blackstone well

With its water, crystal clear,

Used by the people of the village

For many a countless year.

We'll sit down in the silence

And we'll just look all around,

If silence can be golden,

Down here, there's not a sound.

We'll walk back up to the open road

And walk down past the mill,

We'll take a look at the lapping room

And Ogles Grove, that sits there still.

We'll stop beneath the ancient oak

Bent o'er and bare with age,

An oak that has heard and seen it all

If it could turn the page.

We'll talk a while and reminisce

Of all the things that've been,

We'll turn around and take a look

At all the thing's we've seen.

Oh really, what has happened?

Why is there so much light?

Why are the crows so silent?

Oh! What a sorry sight.

The old mill it has vanished,

The lapping room as well.

The glen is desecrated

But it's now too late to tell.

The ancient beech, the ancient oak,

The walnut and the lime,

All destroyed by greedy men,

Driven by the march of time.

Many questions should be asked,

But one comes straight to mind.

I'm sure the answer's somewhere,

Which I'm sure someone will find.

Who gave the man permission,

Whose permission others sought,

To desecrate an ancient glen

That evolution wrought?

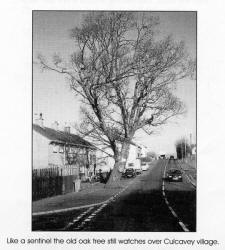

THE CULCAVEY OAK

By Thompson Crossey

This is an ode about an old Oak tree

That has grown in the village for centuries, three

It was here before people, who came at a time

When houses were built of mud and lime.

Ancient Oak still growing in the fertile village soil

Since first you were a sapling, you've seen the natives toil

You've seen the land around you, turned by horse and plough

You've seen the Village born and grow, to where it is of now.

Beside the steam that fed your needs through life

The blacksmith built his shop and forge

For, without the blacksmith's strength and skill

All around, would have remained a gorge.

You've withstood the savage winters

And you have enjoyed the summer sun

You've added splendour to the site

Where you are the only one.

You've seen all kinds of vehicles

Horse drawn, Stem and Gas

Develop from the very first

Until now, when they are all en masse.

As you have breathed the fumes of Whiskey

Of vitrol and clard lime

Because within your realm

There was business of both kinds.

As generations came and went

Of them you were a part

As they walked beneath your boughs

You were quite close to their heart.

The changes you have seen through life

Have been wonderful and great

And people of the village dread

The date, you'll meet your fate.

You are leaning to the East now

From age and weakened root

But we trust, that strong winds from the West

Won't blow, and take you out.

But when you go, as we all know

And your body is destroyed

You're passing will end a chapter

And in your place there'll be a void.

THE KESH BRIDGE

By Oliver Porter

There is a bridge that spans a pleasant stream,

Where old men pause and ponder on life's theme;

And lovers clasp their hands, and kiss, and dream,

Upon this bridge.

There often I have watched the sun go down,

And darkness spread its broad'ning arms, to drown

The glory from behind the mountain brown,

Seen from this bridge.

And standing there in twilight's closing hour,

When ghost-like evening shadows softly lower,

My soul is calmed by nature's soothing power,

Upon this bridge.

There, looking down below full forty feet,

The waters mirror silver stars � a fleet

That makes it like a jewel-studded street,

Below this bridge.

The city has its charms, but this I know,

When I am most depressed by common woe,

And long for peace, I lift my heart and go

To this same bridge.

THE RETURN OF THE NATIVE

By Oliver Porter

Gladly some morn at the call of May

My heart shall be lured to roam

By the rose-rimmed, hawthorn-scented way,

And I shall be found at home;

There will I stand at the lone crossroads,

Where the blustering winds go by,

With the Irish rain upon my face,

Under an Irish sky.

And I shall watch at the sudden turn

Where the wee houses come in view,

The twists of smoke from the fires that burn

In the hearth that my childhood knew;

A slow-drawn blind and a welcome smile

That dispel the wind and rain;

The magnet that drew me across the earth �

Her face at the window pane.

BILLY DEAD

By Oliver Porter

In yon lone churchyard by the town*

Where countrymen pass up and down,

He sleeps � the man I loved in life �

Called into silence from the strife.

The hills he loved are capped with gloom,

My hopes, once high, are in the tomb;

No more of pleasure, all things bear

A dreadful presage of despair.

O Life! O Time! From now henceforth

I am a wanderer on the earth;

Even from place to place I roam,

But no more find or seek a home.

A spar on life's broad river thrown,

With no fixed purpose of my own,

I glide along with destiny,

Until the river reach the sea.

Ah, then to prove man's hope, where there

I find him good and great and fair,

And learn that death was not defeat,

My heaven shall be a heaven complete.

* Hillsborough graveyard, County Down.

LINES WRITTEN NEAR EGLANTINE CHURCH

IN 1942

By Thomas Finn

I stood in a grove of beeches sheltering from the

rain,

At the top of an eight acre field newly stripped of grain.

At the bottom stands a sweet little church, it's ground so neatly kept;

And from where I stood the trees around it seemed as if they wept.

Although I had seen it many times before, I had

looked, and looked away;

For I never saw it so beautiful as I saw it that Sabbath day.

So when the rain had cleared away I took a dander down

Opened the gate very quietly and had a look around.

There were rhododendron bushes spread out beneath the

trees

And in the newly cut grass stood some beautifully trimmed yews.

There's a lovely creeper on it's walls; it's roof is steep and tiled;

There's not a sweeter place on earth than this Church of Eglantine.

And here in this little Churchyard where many a heart

felt sore,

There stands three wooden crosses I had never seen before.

They marked a plot of ground where our Airmen found their rest.

The ground was red, being newly dug; their graves with flowers dressed.

And those who have never seen it you can take this

word of mine

There's not a sweeter place on earth

Than here at Eglantine.

BUDDING POETS

OF THE FUTURE!

If it were left to the older generation to be the

masters of poetry, the art of putting the rhythm and flow of words

together would in time be lost. A quick perusal through Newport Primary

School Magazines for the years 1979 and 1980 might well provide the

answer!

WINTER

(Jacqueline McQuillan, P.5)

Autumn has ended

And Winter has come,

The trees are all bare in the cold,

We'll look out the window,

To see what's about,

Then well go out and have some fun.

There's one that's not cold,

And he is bold,

Jack Frost he is,

You better watch out he'll chase you about,

He's after your fingers and toes.

OLD AGE

(Lesley Spratt, P.6)

Old age is lonely,

Old age is wise,

Old age is full of thoughts,

Old age is to be young.

Old age is sad,

Old age is forgetful,

Old age is weak through the body.

Old age is toothless,

Old age is grey hairs,

Old age is lean,

Old age is pale,

Old age is staying with memories.

GLIDING THROUGH THE NIGHT

(Robert Finn, P.7)

My name is Nokomis,

I am an Indian boy,

I made a little canoe,

I made him not for toy,

I made him for a journey,

That I could never do,

I hope you think he'll do it,

For there are many dangers to go through,

Niagara Falls might smash him,

Or he might burn by forest fires,

But I can just see him,

Gliding through the night.

THE ANIMALS OF THE FARM

(Christy Davidson, P.4)

Sheep graze on rough pasture,

And roam on rock land,

As long as there is something to keep them in,

To save them from getting harmed.

Dairy cows need water,

And lots of food and grass,

Or else well have no milk to drink,

To pour into a glass.

Some farmers keep hens and chickens,

To lay us free-range eggs,

If he wants to keep them, they'll start oval,

And then with tiny legs.

BONNIE PRINCE CHARLIE

(William Cromie, P.5)

There in the heather a cold figure lay,

With cold and wet fingers and nothing to say,

Watching and listening and looking around,

Suddenly he heard a clash of metal and a sound.

He was very cold and wet and very stiff,

But he knew not to move or even shift.

It was Bonnie Prince Charlie who was very brave,

And he thought a lot of his life which he wanted to save.

THE KITE

(Colin Edgar, P.7)

I'm free, free ever so free,

I can do anything just to please me.

I fly high and low,

To and fro,

And nobody tells me where to go.

I crash to the ground,

And fly round and round. I'm free, free, ever so free,

I can do anything just to please me.

Printed by Trimprint Ltd., Armagh

|