| CHAPTER 20

REV. WILLIAM STEELE DICKSON

"A man of generous heart and noble mind!

A man whose like we ne'er again may find."-LYTTLE

NUMEROUS CLERGYMEN in the County of Down took an active part in the

movement of 1798 - and suffered for it. Prominent amongst these was the Rev.

William Steele Dickson, at that period a minister of the Presbyterian Church

in Portaferry. Mr. Dickson was born on Christmas Day, 1744, at Ballycraigy,

in the parish of Carnmoney. His father, John Dickson, was a farmer. His

mother's name was Jane Steele. William, in his early boyhood, gave evidence

of talent, and attracted the notice of the Rev. Robert White, minister of

Templepatrick (a parish adjoining Carnmoney), who, taking a fancy to the

lad, imparted to him a considerable part of his early education.

At the age of seventeen William Steele Dickson entered Glasgow College,

without having any definite views as to what his future course of life

should be. Under the training of two of the college professors, the

celebrated Adam Smith and John Millar, he devoted his attention chiefly to

law and politics. It was from Millar that he derived the germ of his

political creed. Having finished his undergraduate course, young Dickson was

influenced by his early instructor and pastor, Mr. White, to become a

Presbyterian Minister, and, having gone through the prescribed course, he

was licensed to preach in the month of March, 1767. It was four years before

he received a "call", and during this period he preached as a probationer,

being frequently sent as an occasional supply to various congregations, and

thus becoming acquainted with many prominent families in the counties of

Antrim and Down. Amongst these was the family of Alexander Stewart, of

Londonderry, and grandfather of the notorious Lord Castlereagh.

The year 1771 was an important one in Dickson's life. In that year (on

March 6th) he was ordained to the charge of the congregation of

Ballyhalbert, County Down, and he also became a husband and a father. In

Ballyhalbert he quickly acquired popularity. One of his earliest sermons

preached there was against cock-fighting, and the practice was at once

stopped.

On the 14th of November, 1779, Mr. Dickson, by request, preached a

funeral sermon at Portaferry, on the occasion of the death of the Rev. James

Armstrong, the late minister of the Presbyterian congregation in that town.

Such was the impression created by Mr. Dickson upon the members of the

Portaferry congregation that they shortly after invited him to accept their

vacant pulpit, He accepted that invitation, and was duly installed to the

charge in March, 1780. About this time he began to take a warm interest in

political affairs. In 1783, when Robert Stewart (afterwards the first Lord

Londonderry) stood for the parliamentary representation of County Down,

Dickson laboured most energetically on his behalf. He rode into Downpatrick

at the head of about forty freeholders and well-to-do farmers. They were on

horseback, and paraded the town in Indian file, after which Dickson formed

them two deep and drew them up in front of Stewart's lodgings. All voted for

Stewart. Later on, in 1789, there was another election held for County Down

and on this occasion the younger Stewart (afterwards Lord Castlereagh) was a

candidate. Again did Dickson exert himself, this time with success, and such

was his influence and popularity that in the year 1798 this very Castlereagh

urged the arrest of Dickson, alleging that it would be dangerous to leave at

liberty a man who was so popular amongst the people. But I am anticipating.

It was in the year 1791 that Dickson took the first step upon what turned

out to be for him a dangerous road. In the December of that year he was

sworn in as a United Irishman at Belfast, by the first society there formed.

From the period of his initiation he became an active member, and, was a

leading speaker at numerous public meetings of the organisation.

In 1796, such was the estimation in which Dickson was held by the United

Irishmen generally, that he was appointed Adjutant-General of the United

Irish Forces for County Down, He was a courted and honoured guest in the

houses of wealthy merchants of Belfast, where his sparkling wit kept the

table in a roar. His presence as a preacher was ever welcome, crowded

audiences listening with delight to his burning eloquence. But with all

this, he was not unmindful of his congregation in Portaferry, and he often

declared that his happiest hours were spent by the firesides of the farmers

in various portions of the Ards.

As might be expected, Dickson had his enemies, and many efforts were made

to destroy his popularity. In October, 1796, a most determined attack was

made upon his congregation. A poor man named Carr, in hope of reward,

conveyed certain information to Colonel Savage of Portaferry. This was

quickly carried to Lord Castlereagh, who at once ordered the arrest of

several of Dickson's most respected hearers. They were confined for a night

in Portaferry and removed next day to Dublin and Carr, for safety, lodged in

Kilmainham, he with his wife and and family, being comfortably supported. It

was hoped that Carr's evidence would lead to the arrest of Dickson also, and

that gentleman was urged to seek refuge in flight. This he refused to do,

and every week until the end of December he visited his imprisoned hearers -

a circumstance which increased the hostility of his foes against him.

And here an incident may be related as illustrative of the measures taken

by the minions of the Government to secure the conviction of certain

suspects. Dickson, having occasion to go to Dublin, visited a number of

gentlemen from Belfast who were then prisoners in Kilmainham. Here he

learned that Carr, the informer, was in solitary confinement; that he was

frequently visited by people from Dublin Castle, and treated with great

severity, because his information fell short of his promise! The unfortunate

creature was, at times, nearly distracted from a sense of his guilt, and the

condition of his wife and children, whom his tempters had then abandoned,

and he felt that he could not prosecute, to conviction, a single individual

against whom he had sworn.

Dickson enquired how this could be ascertained, and was informed that, if

he chose, he could hear it from Carr's own lips. "By all means let me hear

it!" said Dickson.

One of the prisoners (Smith) immediately left the place in which the

interview was being held, and, returning in a few minutes said -

"Come with me, Dickson; the yard is clear."

Smith, Dickson, and another prisoner adjourned to the jail yard.

"Keep close to the wall here," said Smith to Dickson, who did as

directed.

Then Smith took a ball from his pocket, and, after various trials,

succeeded in throwing it through a window over the spot where Dickson stood.

It was Carr's cell, and the man, who understood the signal, threw back

the ball, and speaking from the window, asked what was wanted.

"Any news?" enquired Smith. "Na, no a word," answered Carr.

"No hope of your release?"

"No a bit. It was the black day fur me that a said a cud gie my

infumashin aboot dacent men. Oh, dear! Oh, dear! What am a tae dae, an' my

wife n' weans stervin'?"

For a length of time Carr went on lamenting his condition; telling what

he had done, and what he had suffered. The tale was an infamous one!

"Tell me, do you know the Rev. Mr. Steele Dickson?" asked Smith.

"A dae," said Carr, "and' he's as dacent a gentleman as iver brauk breid."

"Isn't he a United Irishman'?"

"A'm tell't he is."

"Don't you know him to be one? Have you ever met him at any of their

meetings?"

"Niver in my life," said Carr. "Nor a niver heerd o' him bein' seen at

ony."

"Haven't you been promised money if you would give information that would

lead to his conviction?"

Carr did not reply.

"Don't be afraid," said Smith, "we are prisoners like yourself, and you

know I have promised to help you, if it be in my power to do so."

After another pause Carr said -

"A wuz promised a thoosan' pun' if a wud sweer against Mr. Dickson tae

convict him!"

Dickson bore cheering news from Kilmainham to his friends in Downpatrick

jail. They were tried at the following assizes and released.

The Rev. James Cleland was one of Dickson's bitterest enemies. That

clerical celebrity had been tutor to Lord Castlereagh. It would, perhaps, be

more accurate to say that he was Castlereagh's footman. Many people in those

days spoke of him as "master of the croppy-hounds, pointers and terriers."

He was subsequently vicar of Newtownards. Cleland exhibited remarkable zeal

in the prosecution of Dickson's friends, and was not a little chagrined at

their release. He had hoped for great things from Carr, but was bitterly

disappointed. As will be seen by the previous chapter, Cleland had found

another tool in the person of Nick Maginn of Saintfield.

The Clelands built Stormont Castle out of their gains, and are buried

under an imposing monument at Dundonald. They had much trouble and sorrow

laid on them.

At the time of the interview, already related, between Cleland and Maginn,

Dickson was in Scotland, where he had been on a visit to his wife's uncle,

from early in the previous March. He left Scotland in April and landed in

Donaghadee. Having sent his servant on to Portaferry with his luggage,

Dickson turned his steps towards Granshaw, with a view to visit the Grays

and other friends in that neighbourhood.

CHAPTER 21

A MARE'S NEST

"Conscience makes cowards of us all!"

JOHN DAVIS, Dickson's servant, pushed on from Donaghadee towards

Portaferry, glad at his master's return and dreaming of no harm. A surprise

was in store for him.

John reached the ancient little town in safety, and had come near to the

Market-house, where he was surrounded by a number of soldiers, who made him

a prisoner and carried him and his master's luggage to the guard-house. The

scrutiny of the baggage which then took place was so minute as to excite the

ridicule of the officers who stood by looking on. Everything in which aught

of a dangerous character was likely to be concealed, was tossed, shaken, and

turned outside in.

Suddenly, something which emitted a sharp, metallic sound fell upon the

pavement.

"Ha!" exclaimed a soldier, "what is that?" The others started back.

It was a small box, manufactured of steel and almost completely covered

with rust.

Very suspicious, indeed, it looked! What could it be?

That it was an instrument of destruction all were agreed. After a lapse

of some time, one of the soldiers, more courageous than the rest, picked it

up. His courage was applauded by the others who, somewhat ashamed of their

conduct, now gathered round him.

The man strove to open it, but in vain. One after another tried, with a

like result.

"Fetch a hammer!" cried he who first seized the box. "I'll smash the

damned thing! It must contain a hidden spring!"

While someone went in search of a hammer, Captain Marshall, who had been

an amused spectator of the scene, stepped forward and lifted the box.

"Look here," he said, "it is the rust that prevents you from opening it.

Hand me a knife."

Half a dozen pocket knives were quickly tendered. Taking one of these,

the captain scraped off a quantity of rust, inserted the edge of the knife

at the proper place, and the infernal machine flew open. It was a tobacco

box!

There was a hearty laugh, in which the discomfited soldiers joined and

honest John was permitted to depart in peace.

The seizure of Dickson's luggage is easily accounted for. Maginn. the

informer, had volunteered to Cleland the information that Dickson had gone

to Scotland to form and promote there Societies of United Irishmen.

The story was a pure invention.

As for the infernal machine, Dickson tells the particulars connected with

it in a book which he afterwards wrote and published. The tobacco box was a

very large one. It had formerly belonged to a sea captain. On its being

shown to Dickson, he admired it as a curiosity, became the possessor of it,

and brought it with him to Ireland.

Cleland and Maginn were deeply disappointed by the result of the raid

made upon Dickson's effects. They applied themselves with renewed energy to

the object which they had in view, and the reverend gentleman was placed

under close watch. His every step was dogged. What success attended the

efforts of these base and treacherous creatures - these human bloodhounds -

will but too soon be made apparent.

CHAPTER 22

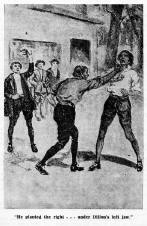

A PUGILISTIC ENCOUNTER

"A joke's a joke but there's nae joke in that!

As Jamey Dillon said tae sturdy Mat."-OLD BALLAD

FROM the day of Warwick's arrest, Drumawhey became uncomfortable quarters

for the informer Dillon. FROM the day of Warwick's arrest, Drumawhey became uncomfortable quarters

for the informer Dillon.

His business dwindled away; the few customers who called and drank his

vile whiskey, did so from curiosity to see the man chiefly. As for his

school, it was completely broken up.

Dillon thought that in a short time the affair would blow over; he would

be comforted by a handsome Government reward, and his neighbours' tongues

would be silenced, while his improved financial circumstances would obtain

for him at all events a show of friendly feeling in the district.

Not many days passed ere he had an instance of the depth of the

indignation which he had stirred amongst the people.

He wanted some trifling bit of smith-work done, and, throwing on his

coat, he stepped across to his old acquaintance, Mat McClenaghan.

He found several men in the smiddy and round the door, engaged in

conversation. Not one of these men so much as nooded to Dillon, or responded

in any way to his salutation, given in a tone of forced cheerfulness.

"Well, Mat," he said, stepping inside, "that's a fine bracing day." "Weel,

ye hae yer share o' it," was the dry response.

Dillon did not appear to notice the reply or its tone, but, drawing from

his pocket a piece of iron chain, explained to Mat what he wanted done.

Mat looked at him sullenly, and went on with his work.

"I can wait till you have finished what you are at," said Dillon. Mat

laid down his hammer, and, looking Dillon straight in the face, said -

"If ye wait till a lift a hemmer fur you ye'll stan' there till

doomsday."

"Nonsense!" said Dillon, forcing a laugh; "my money's as good as other

people's."

"It's naethin' o' the sort!" said Mat, whose temper was rapidly rising.

"How is that?" asked Dillon.

"Ye ken very weel athoot me tellin' ye," said Mat. "If ye want a chain

tae tie yersel' tae a stake, a'll fix it fur ye, but yer dirty money wull

niver gang in my pokit."

"Why do you speak to me in that way?" said Dillon, in turn growing angry.

Mat threw down his hammer, and, stepping up to Dillon, said - "Bekase ye

hae nee bizzness here."

"Mebbe he's lukin' fur pikes," said one of the bystanders.

This was a home-thrust, and Dillon, naturally a passionate man, became

angry.

Turning round to the person who had made the remark, he said

"And if I wanted pikes, my man, I think I wouldn't have far to look for

them."

"An' if ye wud find ony here," said Mat, "ye wud hae anither errand tae

Newtown fur the sodgers."

"What do you mean?" said Dillon.

"A mean this," said Mat; "the sodgers wuz here since lukin' fur pikes,

an' a hae a strong notion that you sent them. At ony rate ye tuk them tae

his honour, Mr. Warwick."

"I merely did my duty," said Dillon, sullenly.

"Very likely," said Mat, drily, "There's fowk fur a' sorts o' bizziness,

an' a suppoas the informin' bizziness pays best an' suits you. A hope a'll

leeve tae see yer ugly neck streetched, ye illbegotten, ugly lukin' bluid

sucker ye!"

This was more than Dillon could stand. He lost his temper instantly, and,

clenching his fist, he deliberately struck Mat in the face.

Several of the bystanders rushed forward to interfere but the blacksmith,

by a motion of his hand, restrained them.

Then he cooly took off his apron and threw it upon the anvil. "Noo,

Dillon," he said, "a didnae mean tae dirty my han's on ye, but as ye struck

the first blow, a'll hae a slap back at ye. Cum ootside here, an' these

decent men will see that ye'll get fair play." Dillon saw his error, but it

was too late to retreat. He felt confident he could easily defeat

McClenaghan, so he stepped outside and stripped off his coat and waistcoat.

At the first glance Dillon seemed more than a match for Mat. He was a

big-boned, muscular man. Mat was short in stature, but his daily work had

developed the muscles of his arms to perfection, and his hands were hard as

iron. Neither of the men knew aught of scientific pugilism, of the so-called

noble art of self-defence. It was to be a question of punishment and their

looks plainly denoted that the fight would be one to the finish.

The neighbours gathered round the contestants, but not a word was spoken.

"Noo, Dillon," cried Mat.

As he spoke the two men met with a rush. Mat delivered the first blow,

with fearful force, right upon Dillon's mouth, receiving in return one upon

his chest.

The blood spurted from Dillon. He drew back, paused for a moment to wipe

it with his shirt sleeve, and then made a second dash at his opponent.

Mat was not taken unawares, but from this until the finish the fighting

was fast and furious. Dillon had a fancy for mad rushes, and he struck out

wildly. Mat stood quietly on the defensive; received the rushes from his

opponent steadily, and delivered his blows with the force of a sledge

hammer.

It was evident that the fight would be a short one, Dillon had measured

the sod three times, and as yet Mat had not been knocked off his pins.

As the pair faced each other for the fourth time, Dillon chose to indulge

in a bit of cautious sparring, evidently in the hope of landing a blow with

effect. Mat determined to finish the business at once. Making a feint with

his left which somewhat threw his opponent off his guard, he planted the

right with terrific force under Dillon's left jaw. The sound of the blow

might have been heard at a considerable distance. Dillon went down like a

felled ox, and lay motionless.

"Ye hae killed him, Mat," was the cry, as the spectators crowded around.

"Nee fear o' that!" laughed Mat. "The fellow's born tae be hung."

Dillon was not killed. A dash of cold water in his face brought him

round; he rose to his feet slowly and with a dazed look.

"Hae ye got eneuch?" asked Mat.

Dillon made no answer, but proceeded to put on his hat, coat and vest.

The next moment he slunk off, followed by the jeers and groans of the

half-dozen men who had witnessed the fight.

Mat was never again troubled by a visit from the Drumawhey informer.

CHAPTER 23

A SURPRISE

"The dead alive again! Can this be so?

The future's hid from man, and well 'tis so."-Anon.

THE TIDINGS communicated to the Reverend William Steele Dickson, when he

arrived at Betsy Gray's house, filled him with sorrow and alarm. The poor

girl was distracted with grief, and the clergyman's efforts to comfort her

were vain.

"Do not weep, my good girl," said Dickson, laying his hand gently upon

Betsy's head. "I feel sure that our friend Mr. Warwick will be set at

liberty. He has committed no crime; there is no evidence against him."

"What do you now think of James Dillon?" asked Betsy. "Indeed, Betsy, I

am not by any means astonished," replied Dickson. "I never had a high

opinion of him. Dear me! How many people, after all, are not to be trusted

in this world."

"He will surely come to a bad end," said Betsy bitterly.

"We must not judge others, dear," said the minister in a tone of gentle

reproach. "There will, however, be a reward for all of us hereafter,

according to the manner in which we have lived."

"Yes, Mr. Dickson, I know that." said Betsy, "But have you not seen these

rewards coming to some people during their lives?" "Yes, Betsy, I have. We

read, too, of many who have, apparently, drawn down upon themselves the

avenging hand of God."

"Then Dillon shall be one of those!" said Betsy, fiercely.

"Hush my girl," whispered the minister; "let us hope for his repentance."

Ah, Mr. Dickson, if you saw poor Mrs. Warwick," said Betsy, the tears

starting to her eyes. "She weeps and laments all day and night. No one can

comfort her."

"I am truly sorry for her," said Dickson. "I shall go to her at once.

After that I shall proceed to Newtownards and learn how fares our friend

William."

"You will send us speedy news, won't you?" said Mary Stewart, pleadingly.

"I shall indeed," he said. "Perhaps I shall bring you news personally."

Dickson partook of some refreshments and rose to leave. He had shaken

hands with Betsy and advanced to where Mary Stewart was sitting.

"Be comforted!" he said. "This is your first trial, and it is a very

severe one. Remember the old saying that the darkest hour is before dawn.

Rest assured, also, that no effort shall be spared to secure Mr. Warwick's

immediate release."

Just at that instant Mary started to her feet and exclaimed excitedly -

"Betsy! whose voice is that? Run to the kitchen. Quick!"

Betsy darted forward and opened the room door. As she did so. the tall,

fine figure of a man pressed past her, and the next instant Mary Stewart was

locked in William Warwick's arms.

"My darling!" he murmured, "I am with you again."

Hurried explanations followed. Warwick had been reprieved. He did not

tell them all, but he spoke cheerfully, and expressed the firm belief that

he would shortly be entirely free.

Betsy went to the kitchen to have her father and brother sent for. She

was horrified to find two soldiers sitting at the fire.

With pale face and frightened aspect the girl darted back to the parlour.

"Mr, Warwick!" she exclaimed, "there are two --men (she feared to say

soldiers in Mary's hearing) in the kitchen."

"Don't be alarmed," said Warwick, laughing, "I should have explained

that, but in the excitement of meeting you all I forgot. Those soldiers in

the kitchen

"Soldiers!" gasped Mary.

"Yes," said Warwick, "they are my guard of honour. At all events they are

to accompany me wherever I go, day and night." "What is that for?" asked Mr.

Dickson.

"To see that I do not escape," answered Warwick. "They seem however, to

be kindly fellows, and I mean to treat them well." Such, indeed, had been

the order of the authorities. Two soldiers were to keep watch over Warwick's

person by day and by night, until further orders. If he should attempt to

escape they were to shoot him down like a dog.

But even on those conditions Warwick was glad to be at large. He went

straight from his prison to his mother's house. At his request the soldiers

stood outside. That was a joyous meeting between mother and son. He told her

all, and then, impatient to see his other friends, started for Granshaw.

CHAPTER 24

SUSPENSE

"Who fears to speak of Ninety-Eight?

Who blushes at the name?

When cowards mock at patriots' fate,

Who hangs his head for shame?"-IRISH BALLAD.

IT WAS the month of May, 1798. Nature had donned her freshest garb. The

skylark, as he soared aloft on fluttering wing, sang loud and cheerily. The

thrush and blackbird piped in the groves and glens. The snowy lambs sported

by their dams in the broad green meadows. The babbling brooks gave forth

their music, and kissed and wantoned with the gaudy May flowers that

blossomed by their margin. The fragrant violets peeped timidly from beneath

the verdant hedgerows. The springing corn gave promise of a glorious

harvest. The fleecy clouds floated like angels' drapery athwart the azure

heavens. The sun rode high in his chariot, showering his golden smiles upon

the gladdened earth, lighting up mountain and glen, hill and dale, castle

and cottage farmstead and hamlet. Earth seemed a very Paradise.

How fared it with old Ireland?

How fared sweet County Down?

Alas, the green fields seemed to smile in mockery. The harvest prospects

cheered not the farmer's heart. The golden grain might bend before the

autumn breeze unseen by him. The corn he sowed might ne'er be reaped by him.

Nay, more, his own heart's blood might nourish the green roots! He heeded

not the duties of his farm. Each sun that rose, each sun that set, still

found him on the watch.

For what?

The call to arms.

Yes, it had come to that! Rash and impetuous the people may have been,

misguided and misled, goaded and forced to arms. The yoke of tyranny was

upon them, and that yoke they must fling off.

In the South the people were in arms and blood was spilled like water.

Ay, and the Patriots were victorious, too, the redcoats scattering before

the impetuous charges of the peasantry like chaff before the gale.

Then why did Down and Antrim sleep? Through treachery and cowardice!

But the treachery and cowardice were not of the people. They had their

origin amongst the leaders!

And be it here remarked that the Government, fully informed of every

movement of the people, having in their possession the leaders' names the

strength of the United Irishmen, and the quantities of arms, could at any

moment have stamped out the agitation, suppressed the rebellion and

prevented a civil war with all its horrors.

Why did not the Government do so?

Because that would not have suited its purpose. Blood must be shed! Creed

must war against creed; faction against faction; Ireland must be divided

against herself, and then her chains would be rivetted the stronger.

These are facts recorded by history, and never attempted to be disproved.

While the South was in arms, the North was in comparative tranquillity.

This was contrary to general expectation, because it was here - especially

in the Counties of Antrim and Down - that the United Irishmen's organisation

first took root.

The 21st of May had been fixed for the rising. As the day approached, the

Northern leaders lost courage and wavered. They became alienated from their

friends in Dublin, and some of them were so base as to become informers;

others were arrested and thrown into prison.

An outbreak was daily, momentarily expected, and Government knew well

that it would be one of terrible -determination. The disaffection in the

North was not the hasty ebullition of turbulent excitement; it had

progressed gradually, slowly but surely; it was the fixed and determined

antipathy with which liberal feeling regarded established institutions. The

rebellion in the South might be the evanescent outburst of a more fiery and

impetuous people, but from Northern coolness, dogged determination and

unflinching bravery, more real danger was to be anticipated. The conspiracy

in the North had been a long-gathering storm, and the material of its

violence had the more reason to be dreaded.

News travelled slowly in those days. There were no telegraphic wires

encircling the earth's surface and winging tidings with the swiftness of the

lightning's flash. The iron horse careered not over the length and breadth

of the land. Newspapers were little larger than modern tracts. The couple

published in Belfast were only issued twice a week, and they devoted more

attention to "Court and Fashion" and "Parliamentary and Foreign News", than

they did to those affairs which concerned the people. Besides these puny

sheets were expensive, and people could not generally afford to buy them.

Thus there was a dearth of news; the wildest rumours were afloat concerning

the doings in the South, an enormous quantity of arms and ammunition were

ready for the men of the North, concealed in every conceivable place,

churches included. The men of the North were ready too, and awaited with

angry impatience the call to arms. But still the summons came not!

And now, even at this critical moment, had severities been discontinued,

had efforts of a conciliatory nature been made, the flame now flickering,

might have been extinguished. But the reverse was the case. Promises were

made but to be broken; proclamations which were commenced by offering an

amnesty merged into sanguinary denunciations, and ended by devoting whole

towns to plunder and destruction by fire. The free quartering of the

soldiery brought terror to Royalists and Insurgents alike. The army, thus

quartered abandoned themselves to all the brutal excesses of which a

licentious soldiery could be capable, and, as the gallant Abercromie stated,

they were formidable to all but the enemy. From the highest to the lowest,

from the noblest mansion to the humblest hut, no one was safe or secure.

Men, youths, ay, and women too, died under the lash; many were strangled

because they could not, or would not, make confessions; hundreds were shot

dead at their daily work, in their beds, in the bosoms of their families -

all to amuse a wanton and brutal soldiery. Torture was inflicted without

mercy and without regard to age, sex, or condition.

Many of the military atrocities in the South have been recorded in

history, and they are beyond belief. The duties of the common hangman were

discharged, in many cases, by the soldiers, some of whom acquired an

unenviable notoriety for their cold-blooded brutality. Sergeant Dunn, of the

King's County Militia, was a monster in human form, whose ferocious cruelty

was perhaps without a parallel, even at the worst times of the French

Revolution Dunn would frequently have quite a number of executions on hand.

On such occasions, he would quietly string up the first victim upon whom his

choice fell, and the others were spectators of the dying man's agonies. When

life was supposed to be extinct, Dunn would cut down the body, strip off the

clothing, all save the shirt and tie it up in a handkerchief, then removing

the shirt from the yet warm body, he would coolly chop off the dead man's

head and roll up the bloody trophy in the shirt. With the remaining victims,

one by one, he proceeded to deal in a similar fashion. When his work was

done he was in the habit of selling the dead men's clothes, watches, rings,

etc., as "Rebel trophies." The heads, rolled up in the shirts, he carried to

his own house, where he fixed them on pikes. In the course of the evening he

would proceed with these over his shoulders to the town-house, where he

mounted the roof and secured them in an upright position to excite the

horror of the people and the ribaldry of the soldiers.

Incredible as the foregoing may appear, it is nevertheless absolutely

true; and Sergeant Dunn had a rival in the person of Lieut. Hepenstal,

concerning whom the late Sir Jonah Barrington has written. This fellow was

six feet two inches high, broad in proportion, and possessed enormous

strength. He was known as "The Walking Gallows." He was an amateur

executioner, and practised the profession in the following manner: When a

prisoner, doomed to die, was brought to him, the lieutenant drew his fist

and knocked him down. His garters he used for handcuffs, and then he

pinioned him hand and foot, after which he advised him to pray for King

George, adding that any time spent in praying for his own damned rebel soul

would only be lost. During this exhortation the lieutenant would twist up

his own silk cravat, slide it over the man's neck, secure it there by a

double knot, and draw the ends over his shoulders. This done, an assistant

lifted up the victim's heels, and Hepenstal, with a powerful chuck, would

draw the man's head up as high as his own, and trot about with him like a

jolting carthorse, until the poor creature was choked to death, when, giving

him a parting chuck to make sure that his neck was broken, the brutal

hangman would fling the dead body to his assistant to be stripped of its

clothing.

When such deeds were done to men of wealth, position and influence, it

may be imagined how the blood of the poor and humble flowed in torrents and

unnoticed.

Little wonder that the Southern Patriots avenged these outrages with

terrible ferocity!

Little marvel that the men of the North panted with eagerness to join in

the fray!

CHAPTER 25

THE PITCH CAP

"For ages rapine ruled the plains,

And slaughter raised his red right hand;

And virgins shrieked and roof-trees blazed,

And desolation swept the land."-ANON

THE MONTH of June arrived, and the men of the North felt the crisis to be

at hand.

It was at hand, and that crisis was doubtless accelerated by events, some

of which cannot be passed over in this narrative. In a lonely hut,

convenient to Newtownards, and quite close to what is now known as "The

Gallows Hill", lived Jack Sloan, a poor blacksmith. Jack was unmarried; a

simple-minded, harmless creature who lived alone, and was much of a recluse

in his habits. He was an excellent tradesman, his charges were light, and he

was - perhaps for that reason - rather a favourite with the farmers of the

district.

In those days every man who worked at an anvil was suspected of

manufacturing pike heads, and every country carpenter was suspected of

making pike handles. These men required to exercise the strictest caution,

and many of them were subjected not only to inconvenience by having their

premises searched, but also to serious ill-treatment at the hands of the

soldiery and yeomanry.

As far as can be ascertained, Jack Sloan refused to have any hand in the

making of pikes. He was certainly not a United Irishman, and when he did

converse with people upon the subject, he invariably urged upon them to have

nothing to do with a rebellion, as no good would come of it. Thus he was, to

all appearance, a loyal subject to the King, and one deserving to be exempt

from the surveillance or interference of his Majesty's bloodhounds.

But the humblest man has his enemies, and Jack was no exception.

Information was conveyed to Colonel Stapleton, at Newtownards, that Jack was

never seen abroad; that his anvil and bellows were at work every night, and

that without a doubt large quantities of pike heads were being turned out at

his forge. The name of the informer has never transpired - probably owing to

what afterwards happened.

One day in the very beginning of June 1798, as Jack worked away at his

forge, he was astonished to see a party of soldiers surrounding the place.

Dropping his hammer and a piece of iron which he had been fashioning into a

gate-bolt, the blacksmith stood gazing in speechless wonder.

"Ha!" cried a soldier, "what's that?"

As he spoke he picked up the unfinished bolt.

But he dropped it more quickly than he lifted it! The iron was hot and

burned his fingers severely.

"Damn you;" he exclaimed as he struck Jack with his musket, "you are

making pikes!"

Jack staggered under the blow, but, instantly recovering himself, he

exclaimed -

"Afore God, gentlemen sodgers, a em not makin' pikes!"

"And what do you call that?" said the first speaker, kicking the

offending it of iron across the floor of the smiddy.

"It's a boult for a man's gate; it is indeed, sir," stammered the

terrified creature '

"You're a rebel and a liar; down on your knees!" said the soldier, seemed

to have command of the party.

Jack did as he was ordered.

"Now," continued the soldier, "say 'God bless his Majesty King George the

Third!'

With quivering lips, but with a loud voice, Jack repeated the words.

"And to hell with all United Irishmen and other rebels!" said the

soldier.

Jack made no response.

"Do you hear me? demanded the soldier.

"A dae, sir," said Jack looking him steadily in the face.

"Then say what I desired you!"

"A wull not, sir," said Jack quietly but respectfully; "a'll never wush

ony man tae gang tae hell!"

"Then you'll soon be there yourself if you don't say as I told you!"

cried the brute, who, thus armed by the law and surrounded by armed men,

bullied a harmless and defenceless man.

Jack was a hero! The world never knew it. He did not even know it

himself.

He was still upon his knees, and, clasping his hands, he turned his eyes

upwards towards the blackened roof of the smiddy, while his lips moved as

though in prayer.

"Open your mouth, sir, and do as I ordered you! Curse the United

Irishmen!"

As the soldier spoke he drew his bayonet and thrust the point of it into

Jack's mouth.

The flesh was cut, and blood trickled from the wound.

Jack rose to his feet amid the laughter and jeers of the soldiery. "A'll

dee furst!" he exclaimed. "A'm a loyal subject o' the King's - God bless and

preserve him - but a'm sorry he has fellows like you aboot him."

This was going too far, but Jack did not know it.

The soldier who had already questioned him next ordered him to give up

any pikes he had.

"A never made a pike in my life," replied Jack, wiping the blood away

that was flowing over his chin.

"You have pikes concealed somewhere!" retorted the soldier.

"Na no yin," said Jack.

"I'll make you find them!" said his tormentor. "Come, lads, tie him to

his own anvil, and give him a round hundred!"

The soldiers gave a cheer, threw down their arms, and seized upon their

victim.

"Try a pitch-cap!" cried one of the party.

"Have you got it?" asked the leader.

"Half-a-dozen", was the reply, as the man handed one to his superior, who

shouted -

"Here, boys, try this first! We'll make him curse all the rebels from

here to Wexford!"

The pitch-cap torture was truly an infernal one. The invention of it is

attributed to the North Cork Militia. At all events, they were the

introducers of it in the County of Wexford. The caps were made either of

coarse linen or strong brown paper, beasmeared inside with pitch, and always

kept ready for service. It was one of these that was about to be fitted upon

the head of the unfortunate blacksmith.

Poor Jack looked on in silence, wondering what was going to happen.

One of the soldiers, seizing hold of the smiddy bellows, brightened up

the fire. Another held the "cap" over the coals until the pitch had melted

and attained boiling heat.

"Ready, boys!" he shouted.

Jack was forced to sit down upon the floor, where he was held until the

instrument of torture was fitted to his head.

His hair was short, a circumstance which proved unfortunate in two ways.

The soldiers at once declared him to be a "croppy", and the boiling pitch,

penetrating to his scalp, burned him like molten lead.

With a yell of agony he dashed the human fiends aside, and sprang to his

feet.

They had no wish to hold him now. That would have spoiled the sport.

The wretched creature rushed from the smiddy, followed by his tormentors,

and darted off at headlong speed to a stream near hand hoping to plunge

therein his burning head. But he was not permitted. No sooner did his design

become apparent than he was surrounded and knocked down. He rolled upon the

ground in agony, his eyes starting from their sockets, a bloody foam issuing

from his mouth.

"Where are the pikes?" cried the leader.

"A hae nane; no yin! Afore God, a hae nane! Oh, let me at the water!"

pleaded the suffering man.

"Where are the pikes?" again demanded the soldier, and as he spoke he

inflicted a deep bayonet wound on Jack's thigh.

For a moment the creature writhed in agony. Then, crawling to his knees,

he pointed to a large beech tree growing some fifty yards off, and gasped -

"Dig at the fit o' that tree!"

"Ha!" exclaimed the soldier, "who was right? Come, lads, follow me, and

let him scratch his head till we return!"

They scampered off to the tree pointed out. The soil encircling it was

fresh and apparently untouched. But they plunged in their bayonets, and

turned up the sod to a considerable depth.

"The old beggar has lied!" they cried, "there's nothing here!" "All

right" said the leader, "we'll give him the two fifties now." The enraged

soldiers returned with a rush to Jack. He was lying upon his face. The

foremost of them seized him by the arms and swung him to his feet. As he did

so, the others uttered a shout of dismay.

Their victim was dead!

He had sent them to the tree for a moment's respite, and in their absence

he had terminated his agonies.

CHAPTER 26

AN IMPORTANT ARREST

"A horse! a horse! nay kingdom for a horse!"

THE ARREST and imprisonment of the Rev. William Steele Dickson are

matters of history. The Reverend gentleman did not dream of the interest

taken in his movements by the Government and he went about his duties

anticipating no interference. On the morning of the 29th of May, 1798, he

mounted his horse and started from the residence of the Rev. Mr. Sinclair, a

Presbyterian clergyman of Newtownards, where he had been on a visit,

purposing spending the day with Major John Crawford, at Crawfordsburn, and

to ride from thence to Belfast in the evening.

On his way to Crawfordsburn he met several gentlemen journeying to

Belfast, who informed him that Major Crawford was not at home, and on

hearing this, he joined the party whom he had met and accompanied them to

Belfast. On the next day he rode to Ballygowan House, the seat of Robert

Rollo Reid, where he spent the afternoon and night. This he did with a view

to be convenient to Saintfield where he intended to buy a horse the

following day.

The 31st of May was Saintfield fair day. Dickson attended the fair and

parade it for several hours looking for a suitable animal This, however, he

failed to find.

He mentioned his errand to some gentlemen whom he chanced to meet, and

one of them said that he knew of a horse which was for sale and which would

suit. The horse was the property of Captain George Sinclair, of Belfast.

Dickson said he would be in Belfast upon the following day, and would like

to see the horse there. On this being said, one of the gentlemen with whom

he was conversing called out "Maginn!" Our former acquaintance, Nick Maginn,

immediately came forward, and was instructed to request Captain Sinclair's

servant to have the horse taken to Belfast next day.

Having so far settled his business, Dickson called at Elliott's Inn,

Saintfield, to get some refreshment, but there was such an amount of hurry

and confusion in the place that he could not, with comfort, obtain a morsel.

He thereupon called with a gentleman friend, David Shaw, where the inner man

was refreshed. That night he slept at Ballygowan, and next morning set out

for Belfast. Here he found that Captain Sinclair was not at home, and the

horses could not be seen.

By appointment of Presbytery, Dickson was to preach at Ballee next day,

and to administer the sacrament of the Lord's Supper on

the day following. He reached Downpatrick at about eleven o'clock on the

morning of 2nd June. Just as he was entering the Inn he was accosted by

Captain Marshall, of the York Fencibles, who appeared excited and annoyed.

"M r. Dickson," he said, "I wish to speak with you."

Dickson invited him inside, and having found an unoccupied room the two

sat down.

"Now Captain," said the clergyman, "I am at your service."

"I have been in Portaferry in search of you," said the Captain, a message

from Colonel Stapleton."

"And what was the nature of it?" said Dickson."

"It appears that when you were at Mr. Sinclair's in Newtownards on Monday

last, you said that a party of the Black Horse had gone over to the

Insurgents. I am to enquire what grounds you had for making that assertion."

"The matter is commonly reported," replied Dickson, "and I merely spoke

of it as a current item of news. It is generally believed to be true."

"Will you kindly write that to Colonel Stapleton?" said the captain.

"Certainly," replied Dickson.

He at once procured writing materials, made out a full statement as

requested, and added that should any further enquiry be deemed necessary he

would be found at Ballee on the two following days, and in Portaferry at

night; that for some weeks afterwards he would be found at Ballynahinch from

noon on Monday till the same hour on Saturday, and, on the intermediate

time, in Portaferry, or the road between the two places.

This letter Dickson read to Captain Marshall, sealed it, put it in his

hand, and saw it handed to a dragoon who was in waiting.

Dickson's object in going to Ballynahinch was to have the benefit of the

Spa water, the use of which his doctor had recommended.

On the evening of the 5th June, while Dickson was sitting in his room, a

servant informed him that a gentleman in the street wished to speak to him.

On going out he met Captain Magenis and Lieutenant Lindsay, of the York

Fencibles, At the request of Captain Magenis, Dickson walked out of town

with him, when the captain, after much hesitation and embarrassment,

informed him that there had been a meeting of yeomanry officers that day in

Clough, and that he had received a letter from Colonel Lord Annesley

ordering his arrest.

"Do not be uneasy or alarmed," said Dickson, "I can bid defiance to

malice itself, provided it be not supported by villainy. Where is your

warrant for my arrest?"

"I have only his lordship's letter," replied Captain Magenis; "as you

have a horse you may take a ride."

The gallant captain wished his friend to escape the exposure of an

arrest.

Dickson declined, and invited the captain and lieutenant to search his

rooms. This they refused to do. He then suggested that they should place

sentinels on the Inn, but this they also refused to do; and it was only

after considerable pressure that a sergeant was sent to the Inn to have an

eye upon the clerical prisoner.

At noon, next day, a Colonel Bainbridge, from Lisburn, arrived in

Ballynahinch, and ordered the removal of Dickson to Lisburn. Having given

this order, he started for Montalto, to pay a visit to Lady Dowager Moira.

Dickson, on learning this, sent a messenger after him to state that he was

in delicate health, and to request that he might be permitted to ride or to

travel in a chaise. The reply was as blunt as it was cruel.

"A chaise, and be damned! Let him walk, or take a seat on the car which

goes to town with the old guns!"

Irritated with this harshness, Dickson determined to walk, which he did.

They started about four o'clock in the afternoon, under a scorching sun, and

reached Lisburn at eight in the evening.

Here he received more courteous treatment at the hands of General Goldie,

who assured him of speedy liberation, and ordered a chaise to convey him to

Belfast. But a disappointment awaited him on his arrival there. Instead of

liberation, the order was - "Carry him to the black hole, and see that he is

kept in safe custody!"

|