Chapter 1

CHILDHOOD BACKGROUND

From my study window in Newcastle I have an unhindered view of Slieve Donard, the highest peak in the Mountains of Mourne that 'sweep dorm to the sea'. One of my favourite rambles, which I take occasionally is to start from Donard Car lark and climb up by the rocky path that follows the course of the river which starts as a tiny stream far up the mountain. I am not a great mountaineer and so I like to stop from time to time to regain my breath while also to admire the scenery and to look back down the path I have followed.

In a sense that is what I am doing now, as I pause at this stage in my life and look back at the path I have travelled and remember those who have been my companions on the way. So naturally I trust begin with the home where my journey started.

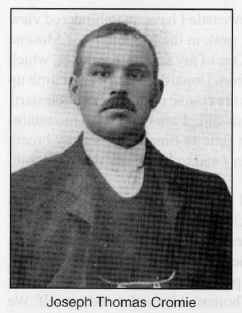

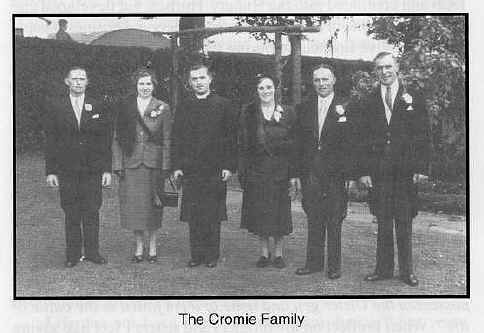

I was born on the 19th April 1929, the youngest of a family of six - Mary, Jane, Robert, Thomas, Alexander and myself We had a sturdy. wholesome upbringing. All of us would pay tribute to the debt we owe to our parents. Father's name was Joseph Thomas Cromie -a tall, erect, heavily built man. He had a genial friendly nature and enjoyed meeting and talking to people. His only formal education was at the local National School. No doubt the syllabus was limited compared with the range of subjects pupils have today, but the subjects be was taught were well taught. I was born on the 19th April 1929, the youngest of a family of six - Mary, Jane, Robert, Thomas, Alexander and myself We had a sturdy. wholesome upbringing. All of us would pay tribute to the debt we owe to our parents. Father's name was Joseph Thomas Cromie -a tall, erect, heavily built man. He had a genial friendly nature and enjoyed meeting and talking to people. His only formal education was at the local National School. No doubt the syllabus was limited compared with the range of subjects pupils have today, but the subjects be was taught were well taught.

For example I never knew him to be unable to spell a word however difficult. When asked how he knew it, he would smile and say,

"Sure I learned it in the Superseded Spelling Book." I am happy to say that I still have a copy of that Spelling book in my possession. Though I would not claim to equal Father in the use he made of it! Mental arithmetic was another of his accomplishments. He could have

worked out involved calculations more quickly in his head than most people could have done on

paper the fruit of a clear agile mind.

Father belonged to a family whose roots ran deep into the life of the fanning community in Comity Down. My Grand-father, Robert Cromie, was one of nine brothers and four sisters raised at Church Hill farm at Ballyroney. Though their father, John, died before the youngest child was born, their mother, formerly Jane Cromie of Rockmount saw to it that each boy was taught the basic farming skills and she succeeded in setting each one of them up on a farm of

his own-no mean achievement.

The ancestral home of the Cromies was at The Valley, in the townland of Seafin, Ballyroney, where the original James Cromie from Perthshire in Scotland settled in 1703.

I am happy to say that the name continues in The Valley farm where William Cromie and his nephew, Richard, maintain the farming

tradition today.

My mother, in contrast to my father, was petite of stature. By all accounts, and her photographs verify it, she was a beautiful young woman with a fine dress sense. My parents were a handsome couple when they were married in Seapatrick Parish Church, Banbridge. Mother, whose name was Margaret Herron, was one of a family of four boys and four girls. A lively household it was and mother had a great love for her parents James and Jane Herron. Her grand-parents had emigrated to the United States

of America taking their family with them and eventually they settled in Newark, New

Jersey. Her grandfather had, however, a bachelor brother, Robert, a wealthy man with

considerable lands at Drumnagally, near Banbridge. Robert appealed to his brother when

emigrating to allow his son James to remain in the family farm at Scarva Road, promising that

if he did he would make him heir to his lands and property. So it was that my grandfather

remained in Ireland and brought up his family, first on the farm at Scarva Road and then

at Drumnagally. was a beautiful young woman with a fine dress sense. My parents were a handsome couple when they were married in Seapatrick Parish Church, Banbridge. Mother, whose name was Margaret Herron, was one of a family of four boys and four girls. A lively household it was and mother had a great love for her parents James and Jane Herron. Her grand-parents had emigrated to the United States

of America taking their family with them and eventually they settled in Newark, New

Jersey. Her grandfather had, however, a bachelor brother, Robert, a wealthy man with

considerable lands at Drumnagally, near Banbridge. Robert appealed to his brother when

emigrating to allow his son James to remain in the family farm at Scarva Road, promising that

if he did he would make him heir to his lands and property. So it was that my grandfather

remained in Ireland and brought up his family, first on the farm at Scarva Road and then

at Drumnagally.

The Herrons were an old Presbyterian family interrelated to the Dunbars who were Banbridge benefactors. In the Subscription controversy within the Presbyterian Church in the middle of the 19th century, the

Herrons adhered to the Non-Through Changing Scenes

Subscribing body within the Church. Mother used to tell how her great uncle Robert, being a bachelor, had a housekeeper who looked after his affairs. On one occasion a curate, who had recently arrived in the Parish Church, set out on a house-to-house visitation of the parish. He called at Drumnagally and being met at the door by the housekeeper inquired if she were an Episcopalian (as Anglicans were generally called in those days). She replied that she was Roman Catholic to which he responded,

"Too bad, too bad.'" Then he inquired if the master of the house were Episcopalian. She replied,

"No, he is a Unitarian" (as Non-Subscribing Presbyterians were generally called), to which his response was,

"That's worse, That's worse!" Such was the spirit of tolerance in those days.

When my grandfather James fiction - a Non-Subscriber. married Jane Beck an orthodox Presbyterian. neither was happy to join the other's church, so they compromised and became members of the Church of Ireland and so their family, including my mother, were brought up as members of Seapatrick Parish Church. When they died, however, my grandparents were laid to rest in the family burying ground in the Old Meeting House Green in Banbridge.

After my parents were married on the 6th April 1907, they bought the farm at Ballydown. At that time there was only a dwelling house and no other buildings. The first thing my father did was to invite his cousin Hugh John Cromie from Magheral, a builder, to erect a byre, a stable and a barn - the basic necessities of accommodation to begin farming. Thus started, my parents slowly developed their pattern of mixed fanning while coping also with the arrival of their family.

Life can not have been easy for them during those years when the family was very young and my father was working single-handed. Tragedy befell him, however, in 1924 when he

was involved in a serious accident. He heard a neighbour's runaway horse galloping up the road pulling a farm cart. My father ran out to stop the horse. He grabbed hold of the reins, but tripped and fell. The wheels went over his legs, breaking both in several places. This resulted in a lengthy period in Banbridge Hospital and bed-resting at home. Complications set in, followed by recurring periods of blood poisoning. The result was that he remained incapacitated as far as manual work was concerned for the rest of his life and he generally walked with the aid of two walking sticks. My oldest brother Robert was only 13 years of age at the time of the accident and he had to

leave school to do the ploughing that winter.

It was remarkable that the family not only remained solvent throughout the years of the Great Depression, which began in 1926 and continued into the Hungry Thirties. but developed and prospered in spite of adversity. Many farmers and business people did not survive financially during that period. Great credit must undoubtedly go to my mother - who not only looked after my father and the family but who was also a very industrious person. One thing, which my parents instilled very strongly into the family, was what is often called the Presbyterian Work Ethic. An ancient Cromie Coat of Arms, granted many years ago, has the motto,

'Labor Omnia Finch'-'Work Conquers All'. As a family we were never allowed to forget that motto. And I am sure it contributed much to the

`victory over adversitv' during those difficult years. In an earlier generation, my father's great uncle, The Rev Thomas Cromie, the first minister of Bessbrook. wrote regarding his family at The Valley, Ballyroney:

"They, all possessed the Ulster grit and none of them failed in the battle of

life". When I reflector my brothers and sisters I feel like saying `Amen to

that'. It was remarkable that the family not only remained solvent throughout the years of the Great Depression, which began in 1926 and continued into the Hungry Thirties. but developed and prospered in spite of adversity. Many farmers and business people did not survive financially during that period. Great credit must undoubtedly go to my mother - who not only looked after my father and the family but who was also a very industrious person. One thing, which my parents instilled very strongly into the family, was what is often called the Presbyterian Work Ethic. An ancient Cromie Coat of Arms, granted many years ago, has the motto,

'Labor Omnia Finch'-'Work Conquers All'. As a family we were never allowed to forget that motto. And I am sure it contributed much to the

`victory over adversitv' during those difficult years. In an earlier generation, my father's great uncle, The Rev Thomas Cromie, the first minister of Bessbrook. wrote regarding his family at The Valley, Ballyroney:

"They, all possessed the Ulster grit and none of them failed in the battle of

life". When I reflector my brothers and sisters I feel like saying `Amen to

that'.

One of my great problems as a child was shyness and I believe this was intensified by the fact that the rest of the family were all older. Children vary greatly in temperament. Some undoubtedly need to be curbed otherwise they would make other people's lives unbearable. There are others, however. who need to have their self-confidence encouraged and strengthened to overcome their native shyness. Parents, teachers and older members of the family have a vital role to play in this aspect of children's development. While on the whole I have managed, by God's help, to overcome that annoying shyness. I have to admit that at times its shadow still dogs me even after over fifty years in public life.

SCHOOL DAYS

It often amazes me when I bear of children going to Nursery School from the age of two and a half and Primary School by the time they arc four. I did not start school until I was nearly six and a half. This was mainly because I had to walk to school - about two miles. My sister Jean brought me on the carrier of her bicycle the first two mornings; but thereafter I had to walk. There were very few cars and no school buses in those days. I teamed up with the children from two neighbouring houses and we became close friends. There were the Thompsons; Stanley, Norman and Bertha, who came to the

Abercorn School with me and the Gordons: Mary, Kathleen. Ellie, Jim and Iris. who went to the Roman Catholic School in Dromore Street. Rain, hail or snow we all walked to and from our schools together. Those were good days and we enjoyed a lot of fun especially on the way home -though we had to be home by the time the four o'clock bus came down the Rathfriland Road or we had to explain the reason why!

One of the reasons why we might, on occasions, be a bit late was Fleming's bull! These were neighbouring farmers who always kept a bull with their dairy herd. One of their bulls was particularly ferocious and when he saw us coming he would rush to the hedge roaring and snorting as he looked for a weak spot

where he could break through into the road-which he frequently succeeded in doing. We had to climb over a gate on the other side and make our way through the fields towards home until eventually we got beyond the sight of the bull. Fortunately none of us ever came to any harm, we were all sufficiently

`country-wise' to survive.

Once I was old enough I was given chores to do at home. This meant changing into my farm clothes to feed calves, pigs, hens etc. At busy seasons in spring and harvest I worked in the fields after school and on Saturdays, scaling manure, setting potatoes, carrying corn for sowing, thinning turnips - pulling flax and spreading it, tying hay and corn, gathering potatoes. All this was good outdoor work-and I enjoyed it. The only trouble was that often I was just too tired afterwards to do my homework!

My three brothers were all full-time on the farm and each had his particular responsibilities. Robert was mainly the horse man, Tom looked after the cows, and Sandy was responsible for the fattening cattle and pigs, though everyone helped where extra help was needed. If however they were all busy at the one time I was likely to be called on by any or all of them. There were times when my mother used to say 'We would need two or three

Howards around here!'

Eventually my mother realized there would have to be a change if I were to succeed at school, so she

'laid down the law' that when I came home from school I must do my homework first and I was only allowed to help with the farm work after the homework was finished. This was a great relief to me.

The Abercorn School had been built in 1931 and opened by the Duke of Abercorn, the first Governor of Northern Ireland. To a small child it seemed a huge building and I always remember the Assembly Hall as being a very large room with a very high platform. Fifty years later when I paid

an official visit to the school as Moderator and was shown into the Assembly Hall, I was amazed at how small it was and how low was the platform! I recalled the poem by Thomas Hood, which I learned at school:

|

"I remember, I remember,

The fir trees dark and high;

l used to think their slender tops

Were close against the.sky;

It was a childish ignorance,

But now its little joy

To know, I'm farther off from heaven

Than when I was a boy." |

James Carson was the Principal and he was a stem disciplinarian. If the old slogan were true:

'Spare the and and.spoil the child', there should have been no spoiled children in the

Abercorn! My first teacher was Miss McKeown, a gentle, lovely person who was ideal for being in charge of the Infants' Class. She, together with Miss Mehaffey and Miss Stannage, had a

humanising influence in the school. I continued at the Abercorn until

6th Standard when I sat the entrance examination for Banbridge Academy.

The old redbrick building by the edge of the River Bann housed three separate institutions- the Carnegie Public Library, the Technical School in the evenings and the Banbridge Academy by day. It was not until several years after

I left that the school acquired its handsome new buildings on the Lurgan Road, incorporating the house of the late Mr. Howard Ferguson.

The old redbrick building by the edge of the River Bann housed three separate institutions- the Carnegie Public Library, the Technical School in the evenings and the Banbridge Academy by day. It was not until several years after

I left that the school acquired its handsome new buildings on the Lurgan Road, incorporating the house of the late Mr. Howard Ferguson.

Dr W Haughton Crowe was the Headmaster. He was a kindly man who maintained a humane discipline and while he had a cane in his office it was hardly ever used, except in the most extreme circumstances. The Academy had some very

good teachers - and some not so good - but we managed to survive

them! I never cease to be grateful for the good ones. Them I engaged in the full round of the school's activities including such

sports as hockey, rugby and athletics within the limitation, of wartime restrictions. The Academy was a happy

school and I look back on my time there with grea pleasure.

Chapter 3

PRESBYTERIAN UPBRINGING

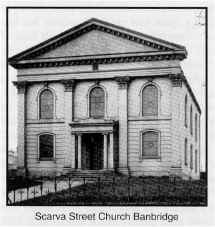

Since the original James Connie come from Scotland and settled at The Valley. Ballyroney in 1703, the Cromies hove been mainly staunch Presbyterians. When

my grandfather. Robert Cromie and his young wife. Mary Bell. came John Church Hill, Ballyroney to take up homing at Doughery and

Tullyear, Banbridge. they had the choice of joining any one of four different congregations - Loughbrickland. Bally down, Bannside or

Scarva Street. They chose to join Scarva Street congregation in Banbridge. In time

their four sons were baptised there. While one of them, Henry, on his marriage returned to

live at Ballyroney and joined the Church where his forebearers had belonged, the other three continued as members of

Scarva Street and brought up their families there. Many of them have in turn married and continued to bring up the next generation also in

Scarva Street At the last count the Minister reckoned there were 56 Cromies on the Roll of

Scarva Street Church, all descendants of Robert and Mary Cromie!

In my early upbringing Religion and Life belonged together. There was no feeling of sanctimoniousness about church-going and religious observance.

It was simply part of the pattern of daily life. Going to Sunday School was as natural as going to Day School and no one questioned either. My sister Jean was a Sunday School teacher and she brought me

along and introduced me to my first teacher. Miss Ruby Campbell. She was a very caring, lovable person and I was sorry when

she left to marry a farmer near Dromore. Sunday School was a very happy, positive experience. None of our teachers had any professional training. but

they had a great love for the children and a great understanding not only of the Bible but also of life. John Ervine, the Sunday School Secretary and later Superintendent was

full of life and personality. Every year at the Annual Social he was called on to sing

'Where

did you get that hat:' ' It became a firm favourite and fifty years, later the children

were still requesting it.

In those days considerable emphasis was laid on learning by heart or by rote. It this way we built up a memory bank of Metrical Psalms and

Hymns which were regularly sung in Church. Great passages of Scripture like

Isaiah 53 & 55, I Corinthians 13, John Chapters 10 &

I4. The Beatitudes. etc etc.. gave a fine background of Biblical knowledge. Then there was the Shorter Catechism, which I learned to repeat

from the beginning to end without a mistake. Many times when I was at College, and in the years since then. I

have been glad to recall those Catechism definitions of the great Doctrines of the Christian faith

I fear that with the omission of such memorising today many of our children

leave Sunday School as virtual religious illiterates who have only a very hazy idea of Christian belief and so they

are liable either to become 'drop-outs' from the life of the Church. or to become easy prey for the

purveyors of fringe sect, and sectarian dogmatists.

In Scarva Street Sunday School we were not only given knowledge we were also encouraged to think and make that knowledge our own.

When I reflect on my early years I can not remember a time when I did not believe

in God and I never remember a day when I did not pray to Him. Learning to say `The Lord's Prayer' and finishing it with

'God Bless us all' is one of my earliest memories and it has remained my practice

in my private devotions to this day. "Jesus loves me this I know, for the

Bible tells me so" was the first Hymn I learned before I went to Sunday School and it is still my favourite Children's

Hymn. Nobody. I am Thankful to say. ever tried to Impose an adult experience on

my childhood understanding and belief. It was all very real to me and as I became a little older my great delight was to dress up like a minister and conduct a service on a Sunday evening with the rest of the family joining in dutifully as the congregation. Once or

twice Some of the older members of the family tried to make a joke of what I was doing- not without good reason I

am sure- but my father rebuked them severely and told them that as far as I was concerned this was serious and they had to sit

up and listen - which. to their credit. they did! I remember on one occasion I was using

my father's big armchair as a pulpit. I was in the full flight of my sermon when I

must have leaned forward too far, for the chair up-ended and I landed in the middle of the congregation!

These little services did mean a lot to me. I used to spend most of the Sunday afternoon writing

a 'sermon' based on the lesson I had learned in Sunday School in the morning, choosing hymns and selecting prayers front my

mother's Church of Ireland Book of Common Prayer. I have no doubt that my first stirrings of a call to the Ministry can be traced back to those Simple childish little services

on a winter Sunday evening.

In any young persons spiritual development there are times of Challenge and Commitment that stand out in their

significance. Such for me was my attendance at the Communicants' Class. There

were in fact only two of us- Fergus Graham, a big well-built ginger-haired lad and myself. one of the things that impressed both of us was the thorough, disciplined was' our minister. the

Rev William Moore, proceeded to teach us what was involved in becoming Communicant Members of the Church.

In any young persons spiritual development there are times of Challenge and Commitment that stand out in their

significance. Such for me was my attendance at the Communicants' Class. There

were in fact only two of us- Fergus Graham, a big well-built ginger-haired lad and myself. one of the things that impressed both of us was the thorough, disciplined was' our minister. the

Rev William Moore, proceeded to teach us what was involved in becoming Communicant Members of the Church.

We soon realised that these classes were not going to be any easy 'push-over'. We had a Booklet to read,

Catechism questions to learn or re-learn, passages of Scripture to study and at the

end of the course. written answers to be given to such questions as 'What is Christian?' 'What

do I consider is the central importance of the Lord's Supper'. 'What difference should being

a Communicant Member of the Church

make m my life?'

Knowing these were the kind of questions with which we were going to be faced, I

said to Fergus Graham that we would have to take this whole matter very seriously or else not go through with it.

I prayed to God to give me Grace not

only to put my whole trust in Jesus Christ as my personal Lord and Saviour, but also to follow the leading of His Spirit as to what He would have me do with my life. I remember clearly one evening going to the field to bring in the cows for milking and

I stopped at the gate leading into the held and there in prayer I committed my life into God's hands. For some people conversion means opting to come into the Kingdom, for others it means opting to remain in the Kingdom and to affirm the faith in which they had been nurtured. For both sets of people the challenge and the response are equally urgent and vital for their future weal or woe.

For me taking my stand as a Communicant Member of the Church of Jesus Christ was the most important decision of my

life and has brought unnumbered blessings in its train. After that time Fergus Graham and I went our several ways and we lost contact with one another. Fifty years later we met up again when he came to see me after a Special Police Service in which I was involved as Moderator. I was delighted to meet him and learn

that he had been a Chief of Police in Canada. We both recalled with gratitude our time together in the Communicants' Class and the difference it had made to both our lives as we had sought to follow in the footsteps of the Master.

For me taking my stand as a Communicant Member of the Church of Jesus Christ was the most important decision of my

life and has brought unnumbered blessings in its train. After that time Fergus Graham and I went our several ways and we lost contact with one another. Fifty years later we met up again when he came to see me after a Special Police Service in which I was involved as Moderator. I was delighted to meet him and learn

that he had been a Chief of Police in Canada. We both recalled with gratitude our time together in the Communicants' Class and the difference it had made to both our lives as we had sought to follow in the footsteps of the Master.

It may be that our Minister, Mr. Moore, was somewhat disappointed that there were only two of us in

his class that year, instead of perhaps a dozen, but he certainly never showed it. His diligence and faithfulness were used of God to bring great blessing into both our lives.

Chapter 4

MEMORIES OF WARTIME

Though I was only ten years old I remember well Adolf Hitler's invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1938 and the debates and discussions which followed the Munich Agreement when the British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, arrived off the plane waving a piece of paper in the air and announcing,

'Peace in our time'. Some people accepted Chamberlain's assurance of peace but many did not. Among the latter was Andy, a neighbouring farmer, who said there would never be prosperity for farmers until war came! He danced on the road saying:

"This piece of paper is worth nothing - there is going to he a war." Sadly be was proved to be right and on Sunday

3rd September 1939, we arrived in Church to find that the Rev Win. Moore had brought his wireless set into the pulpit because war was likely to be declared. He switched on in due course to hear the announcer saying,

"This is London, please stand by for an important announcement. " Then came the voice of the Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, saying,

"Since the Nazi forces who have invaded Poland have not withdrawn following the joint British and French ultimatum, we are

at war with Germany. "Those were solemn words I shall never forget. That day the sun was blacked out with thick dark clouds which poured forth torrential rain, accompanied by thunder and lightening. The heavy foreboding

sky matched exactly the dark feelings of fear and depression that gripped most people's minds.

I don't remember the sermon Mr. Moore preached that day, but I do remember singing the

46th Psalm:

"God is our Refuge and

our Strength,

In straits a present aid.

Therefore although the earth remove

We will not be afraid. " |

Britain was not prepared for war, so the months that followed saw a tremendous galvanising of the nation behind the war effort. Chamberlain was not considered to be a strong enough leader to cope with the situation and so Winston Churchill replaced him at the head of a National Government. Churchill proved to be the man for the hour - especially after the fall of France, which left Britain to stand alone. His speeches broadcast to the nation had an electrifying effect upon the people giving them courage in the face of adversity.

Recruitment drives were held all over the country to encourage young men and women rejoin the forces. Those who were engaged in essential work at home were encouraged

to join either the Civil Defence or the Home Guard. A competition was held for a poster slogan. Though I was only a schoolboy I had the temerity to enter a couplet and was absolutely shocked when the press announced that my offering had been the winner. The Organising Committee presented me with a prize and in due time posters appeared on bill boards in town and country with the words:

"Join the Home Guard or Civil Defence

The Hun will win if you sit on the fence" |

This was my claim to fame in the war effort! Who knows the effect this slogan may have had on

'Dad's Army'!

At school we were encouraged to knit khaki scarves, glows and Balaclava helmets to be sent to the soldiers at the front. The girls in the class were mostly good knitters so they tackled the gloves and Balaclavas while the boys generally confined themselves to the scarves. Knitting was not my strong point.

I remember putting my foot on the end of the scarf and stretching it to help it reach the required length -which eventually it did.

Banbridge was heavily militarised during the war. The first soldiers to arrive were the Yorks. and Lanes. in Kennedy's disused factory on the Rathfriland Road. The Americans, who took the town by storm, were in the Old Brewery, the Belgians were on the Newry Road, the Welsh were in Scarva Street Hall and so the list went on. The Church laid on special functions to entertain the troops, which they greatly enjoyed - especially the suppers.

Often at harvest time the soldiers came out to help bring in the harvest on the farms. I remember asking a young American soldier - a country boy, what he thought of County Down compared with his home state in America. He said he felt very enclosed by all the drumlins and hills of County Down. They made him home sick for the far horizons of the great flat prairies in the mid-west of America. When the American soldiers were sent overseas to prepare for the Normandy landings on 'D' day they came first to Northern Ireland to be orientated and here they were given a warm welcome. Belfast Corporation gave them the Freedom of the City as an expression of wholehearted goodwill.

In the early years of the war and particularly at the time of the Battle of Britain there was constant fear of invasion. The military erected huge concrete

'look-out' posts and zigzag barriers on all roads leading into the town hoping to impede the onward march of the German army!

These barriers were hazardous for traffic to negotiate and were the scene of many an accident. I shall never forget one Saturday; I had taken a load of potatoes to Banbridge (as was my practice on Saturday mornings throughout the winter). On my way home I had stopped to call at a house in Rathfriland Street. A train approached just behind the wall and sounded its whistle. Suddenly the horse bolted. I ran after it and climbed into the cart. With difficulty

I got control of the reins and pulled with all my might but the horse had literally got the bit between its teeth and it galloped on.

I could see the zigzag barriers ahead. All I could do was pray and hope to steer the horse and cart through them. To make matters worse Jimmy Dale was coming with his horse-drawn bread van towards us. Fortunately he realized what was happening and pulled in quickly to the verge, while my run-away horse and I went through the barriers and past him like a streak. There was nothing he could do. Only the grace of God saved me from a serious accident.

'Dick', my dark brown charger, galloped on until I finally got him stopped on Martin's hill, halfway towards home.

The Germans never came to Banbridge. The nearest they came to us was with the sound of their bombers, a heavy droning sound, on the nights they bombed Belfast (15th April and 4th May 1941) causing enormous damage to buildings as they sought to destroy the industrial heartland of the city around the shipyard. Fortunately the shipyard, whilst seriously damaged was able to recover, but whole streets of dense housing were destroyed and almost 1000 people were killed - whole families in some instances were wiped out. 7,500 citizens were left homeless. These raids were followed by streams of evacuees who left the city and came to live with families in the towns and in the country. Some returned to Belfast at the first opportunity, others stayed for two years and more, some because they did not want to leave.

Food rationing was much more severe in the city where, for example, people were only allowed 4ozs butter and 2 eggs per week, whereas in the country we had all the home produced butter and eggs we needed. Household groceries became known as the Rations. Fruit from overseas was virtually non-existent. People became quite excited when the first consignment of bananas arrived in the shops. They were of course strictly rationed to one banana per person. My wife tells how her little sister refused to eat her banana. When asked by her mother why she would not eat it, said,

"Because Kathleen says there are bones in it! " Kathleen did not get Hope's banana!

Nobody ever expected when war was declared that it would last for nearly six years. Great was the rejoicing however when

V. E. Day (Victory in Europe Day) arrived on 8th May 1945. Banbridge town was thronged with people of all ages as they poured in from the surrounding countryside to join in the celebrations. All the churches had arranged thanksgiving services. We naturally attended Scarva Street Church, which was packed to the doors waiting for the announcement to be made.

At 7.OOpm the church bells rang out and a great thrill went through the congregation as Mr. Moore announced the war was officially over in Europe and he commenced the Service of Thanksgiving with the singing of Psalm 124:

"Now Israel may say,

and that truly,

If that the Lord had not our cause maintained.

if that the Lord had not our right sustained

When cruel men who us desired to slay

Rose up in wrath to make of us their prey

But blessed be God Who doth us safely keep

And gave us not a living prey to be

Unto their teeth and bloody cruelty." |

Never have I witnessed a Psalm being sung with such emotional feeling.

When the services were over we all poured forth onto the streets to join in the singing, the dancing and the merry-making which continued well into the `wee small hours' of the following morning.

V J. Day (Victory over Japan Day) had to wait another three months. No one knows

how long the war in the Far East would have continued and how many thousands of

lives might have been lost in the vicious jungle fighting, for the Japanese were

regarded as a particularly cruel, blood-thirsty nation, had it not been for the

dropping of the Atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. These bombs have been

the subject of much debate and heart searching ever since because of the loss of

life they caused. Yet at the time the fact that they brought about the surrender

of Japan and the ending of the war on 15th August 1945 gave great relief to a war-weary people. The six years of World War II had resulted in the deaths of 54.8 million people.

|