|

HENRY HOBART - DROMORE

ARCHITECT

1858-1938

by ROSEMARY MCMILLAN

Forty years ago if you had mentioned the name "Hobart" to

me, I would in all probability have replied, "Capital of

Tasmania". It was the way we were taught in those days.

Recently,

the name has come to my attention again though in a

different context - architecture. On 24th October last, the

Dromore Historical Group was given a talk by Mr. Eugene

Corbett on "The Architecture of Henry Hobart and Samuel

Heron". It is from his thesis that I have gleaned much of

what follows. I also had the good fortune to meet and talk

with Henry Hobart's daughters, the Misses Maureen and Hannah

Hobart, who are responsible for some of the pertinent

comments quoted. Recently,

the name has come to my attention again though in a

different context - architecture. On 24th October last, the

Dromore Historical Group was given a talk by Mr. Eugene

Corbett on "The Architecture of Henry Hobart and Samuel

Heron". It is from his thesis that I have gleaned much of

what follows. I also had the good fortune to meet and talk

with Henry Hobart's daughters, the Misses Maureen and Hannah

Hobart, who are responsible for some of the pertinent

comments quoted.

Henry Hobart was born at Lagan Lodge on Christmas Eve

1858. As a boy he travelled daily by train from Dromore to

Belfast where he attended the Royal Belfast Academical

Institute. His partner of later years, Samuel Heron,

described to me as "another one stuffed full of brains",

also attended the same school, but it is not known if they

were acquainted at that time.

School days over, Henry Hobart was articled to William Lynn

for the sum of �1,000.

"a sum indicative of the high regard in which Lynn was held

among his peers".

In 1890 he returned home to Lagan Lodge, bringing with him

his bride, Miss Maria Lusk of Loughbrickland. Here he set up

his practice in a wonderfully light-filled room, which had

previously been used by his father in connection with his

linen business.

It was here that Hobart developed his talent for

designing buildings for all sorts of purposes. His work was

not only prolific, but displayed a great variety of styles.

He could, and did, design everything from a church to a cow

house. Banks, schools, warehouses and private houses, all

fell within the scope of his work: nor, as the records show,

did he turn away alterations and addition work. His style is

like an irregular verb, you have to learn it to appreciate

its complexities. It ranges from his own version of

free-style classical, reminiscent of the Dutch and English

red brick buildings of the 17th and 18th centuries, to a

plain, almost spartan, design. Miss Maureen Hobart thinks

Prince Charles "would like them better than the Tower

Block".

He went into partnership with Samuel Heron in 1904 and a

year later the firm moved to Belfast. The versatility of the

work from this partnership can be seen across the six counties. Balrath

House - a private dwelling at Donaghmore, Co. Tyrone,

Gardenmore Presbyterian Church, Larne, Co. Antrim, a terrace

of 11 houses at Mill Street, Tandragee, Co. Armagh, Ulster

Bank, Irvinestown, Co. Fermanagh, Technical School,

Magherafelt, Co. Derry.

partnership can be seen across the six counties. Balrath

House - a private dwelling at Donaghmore, Co. Tyrone,

Gardenmore Presbyterian Church, Larne, Co. Antrim, a terrace

of 11 houses at Mill Street, Tandragee, Co. Armagh, Ulster

Bank, Irvinestown, Co. Fermanagh, Technical School,

Magherafelt, Co. Derry.

There was even a venture South to Trimblestown, Co.

Meath, where stables were designed for a Mr. F. Barber.

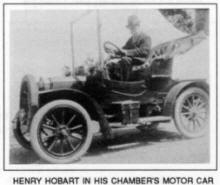

Hobart owned a magnificent Chambers motor which doubtless

proved invaluable in covering so wide a territory.

In the town of Dromore, Co. Down, although there is no

documented evidence of it, one of Hobart's first commissions

appears to have been alterations made to the Cathedral

Church of Christ the Redeemer in 1898 when

"a new chancel and Apse and a broad north aisle were added".

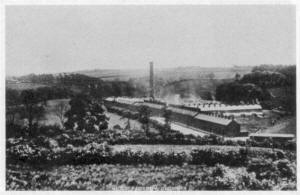

Another of his early commissions was for Messrs Murphy &

Stevenson Limited in 1896, when he designed a row of red

brick terrace houses - Holm Terrace, Lurgan Road. The same

firm commissioned him again in 1907 to design alterations

and additions to the Weaving Factory. The contractor was Mr.

J. Graham of Dromore and his tender for the work was �2,000.

In 1910 the Roman Catholic clergy commissioned him to

design a new Parochial House. This was built in the Church

grounds and the estimated cost for the work was �1,300.

In 1920 the Ulster Bank, appointed him as the architect

for their new branch. The two storey building was inserted

into a terrace in Church Street. The lower storey is of

rusticated sandstone and the upper of red brick.

Undated examples of Hobart designed buildings in Dromore

are, the Gate Lodge at the Cowan Heron Hospital, Neeson' s

Shop, Market Square and numbers 15,17 and 19 Lower Quilly

Road. There are known to be six unlocated houses in Dromore

designed by him - perhaps yours is one of them! Mr. Corbett

sums up his thesis as follows:

"Henry Hobart and Samuel Heron, for their time and place

in architectural history, produced works which, while not

being adventurous, were pleasing to the eye and which were

fine, sensible examples of popular styles and moods

prevailing at the time."

Miss Hannah Hobart puts it more concisely,

"Well, they aren't shoddy"

THE

PINNACLE MEADOW

by JIM HUTCHINSON

In my younger days the field by the river on the

Banbridge Road, and now opposite the High School, was known

as the pinnacle meadow bythe older inhabitants of Dromore.

At that time the field was often the venue for travelling

shows such as funfairs, circuses and the like.

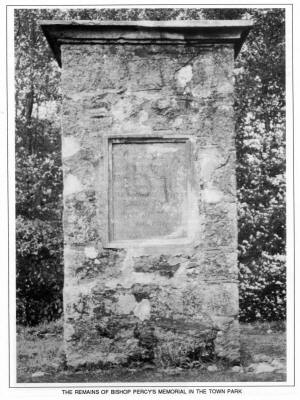

The reason for the name could only be the presence by the

river of a memorial to Bishop Percy, erected by his friend

Thomas Stott. But somehow to me, this squat, rectangular

edifice, hardly suggested a pinnacle, unless the local

people were easy to please pinnacle-wise!

Many years later my attention was drawn to an old

illustration in an equally old book, this showed the

memorial to originally have had a tapering pillar on the top

of what exists. One can only conclude that at some time this

pillar came off. But in it's original state it would have

been, to my mind, more like a pinnacle.

To-day the base of the memorial still stands in what has

now become the Town Park and the name still survives in "The

Pinnacle Youth Club" which exists in connection with the

High School across the road.

'THE MAN WITH THE WEE EYE'

(Contributed by John McGrehan)

The following poem written in the 1920's relates to the

work of weavers at Holm Factory. Murphy and Stevenson were

in business as damask weavers there at that time. The

writers name is not known, although this latter-day 'Rhyming

Weaver' was probably a worker in the factory. Other names

mentioned in the poem are certainly locally familiar.

It would appear that 'The man with the Wee Eye' was a cloth

passer -- a kind of quality controller who was responsible

for checking the finished work of the weavers. Not

unnaturally he had the reputation with the other workers of

being extremely strict in the discharge of his

responsibilities.

Now I have worked in many lands

And many sights I've seen

I've used a pick and shovel

In the little Isle of Green

But at present I am weaving

It's enough to make you cry

For the dread of all, both great and small,

Is the man with the wee eye.He stands behind

the counter

Just like an old bull pup

He sends the young lad Ireland

To bring Jack McDonald up

He looks at Jack so serious

And then to him he says,

"I'll have to fine you in a bob

Unless you mend you ways".

The next to go is McIlwrath

He says to him "My lad

You let the yarn stops out too long

It makes the cut look bad

You will have to be more careful

And keep to the straight path"

"It's a bad hook in the twilling bar"

Says Bobbie McIlwrath.

There is a weaver in the shop

His name is Sammy Mann

He weaves bad hooks right through the cut

And doesn't care a damn

Now just take me I darn't do this

It's enough to make you sigh

He has got a lot of favourites

Has the man with the wee eye.

There's Robbie and McGrehan

There's Turner and there's Burns

The cloth they take up week by week

Would give a man weak turns

But they've got the wind up

And I will tell you why

The man they fear from day to day

Is Mister McAvoy. |

He sent for Willie John one day

And says to him "Look sharp

Get out your shears and pick

Out all the dropped warp"

Now Willie John got angry

His teeth with rage he ground

But he either had to pick the cut

or loose a half a crown.There's McCracken and

McCandless

There is Bingham and there's Mann

There's Martin and McQuillan

They do the best they can.

Sometimes their best's not good enough

And then you will hear the cry

"You will have to make it perfect"

Says Mister McAvoy.

There's Acheson and Hamilton

They dread to hear the call

For when young Ireland comes for them

They very nearly fall.

"There's bad cards in this cut" he says

Then he looks at them so sly

He leads them both a terrible life

Does Mister McAvoy.

Now there's John Cardwell the oiler

He has got a rotten job

For when he puts on too much oil

it comes down with a blob.

And when Law Day comes around again

Poor John will give a sigh

"I've got to loop the loop again

With Mister McAvoy."

If I'm going to keep to weaving

I'll have to get a plate

And put it up my sleeve when I

Go up to meet my fate

But perhaps he will mend his manners

If not. look out my boy

There's murder on the skyline

For the man with the wee eye. |

|

Early postcard of

Holm Factory, Dromore |

|

THOMAS STOTT-DROMORE'S FORGOTTEN POET

by ROY GAMBLE

They say a prophet has no honour in his own

country. In Ulster the same could be said of poets, or

rather, the memory of them, for despite a considerable

legacy of soulful outpourings passed on by local rhymers, it

seems we are poor custodians.

Dromore is no exception. How many citizens

know that the town once could boast of a resident poet? It's

a good few years ago of course (just over a couple of

centuries in fact), nevertheless, some of his writings are

still extant to-day.

Thomas Stott-the poet of Dromore, or as some

called him, the poet laureate of Downwas no Keats or

Wordsworth, nor did he claim to be. He said of his poems:

"They are the recreations of solitary hours snatched from

the hurry of business, furnishing innocent amusement and a

proof that literary recreation is not altogether

incompatible with the pursuits of commerce."

And yet he was a reasonably prolific writer,

contributing regularly to numerous journals and newspapers,

including the Belfast Newsletter and the London Morning

Post, where many of his poems appeared under the pen-name

'Hafiz' (Arabic for observer).

No ploughman poet, like Robert Burns and

John Clare, Stott was born suckling the proverbial silver

spoon, the son of a prosperous Hillsborough linen merchant.

He followed his father's calling and his first poems were

written when learning the linen trade in Waringstown.

He seems to have possessed a penchant for

non-de-plumes. Not only did he extensively employ the exotic

'Hafiz' he also used the colourful pseudonym 'Banks of Banna'

for some of his early poems, possibly in his Waringstown

days.

Stott eventually settled in Dromore, then a

thriving linen centre, and in 1777 he was married in the

town's cathedral to Mary Ann Gardiner, a lady of good

connections originally from Coleraine.

Goto Top

Stott and his new wife set up home in

'Dromore House' - which once upon a time served as the

'Clergy Widows Houses' - and rapidly built up a growing

business with several bleach greens in the meadows beside

the Lagan.

Many of his poems reflect his great love of

Dromore and its citizens. Poems like: "The Mount of Dromore"

in which he celebrates an annual Easter Monday custom of

youthful high jinks on the ancient Norman earthworks. Then

there is a satirical piece (shades of Orwell's 'Animal

Farm') where some educated pigs plead their case for a share

of the 'Liberty, Equality, Fraternity' that was sweeping

Europe at the time. In the "Humble petition of Dromore pigs"

he writes:

". . . We the swine of

Dromore

At a numerous meeting,

To all lovers of pork

This petition send greeting . . .

" And the poem ends:

"Dear liberty then

To us captives restore,

And our thanks shall resound

Through the streets of Dromore."

Incidently, it flows quite nicely to the

tune of Master McGra.

Throughout his life Stott retained a passion

for nature and wildlife. A keen fisherman and gardener, the

solitary hours spent on the river bank and among the shrubs

and flowers and fruitful trees of his garden must have given

him inspiration for such poems as: "the moralizing Trout",

"To May," "Sketch of a fine day in October," "To a

woodlark," and not to be outdone by his contemporary John

Keats- "To Autumn," which he describes as - "Crowned with

sickle and the yellow leaf."

Stott was no effete poet. He possessed a

fine business acumen and thought nothing of setting out from

Dromore on horseback to travel to the brown linen markets in

towns scattered throughout the province.

He wrote of such travels in a poem entitled

"The Brown Linen Buyers" in which he describes the homeward

journey: "Well lined with beefsteak and Irish champagne."

Dromore once had the honour of receiving a

letter from the great adventurer and romantic poet Lord

Byron. Apparently some of Stott's verse had attracted a

scathing attack from Byron during a certain literary

controversy of the time. On learning, some time later, that

Stott wrote merely for pleasure and not for profit, Byron

wrote to apologise for his earlier inconsidered remarks.

In later years Stott struck up a close

friendship with local patron of the arts, Bishop Percy of

Dromore. The memorial which stands in the pinnacle meadow

(which incidently was one of Stott's own bleach greens) was

raised by the poet in memory of the Bishop after his death

in 1811.

Stott died in Dromore house in 1829. He was

buried in the cathedral churchyard, within sight of his home

and not far from his beloved Lagan.

His grave, fourth in line to the right of

the main gate, is marked with this badly faded inscription:

"In the humble hope of

joyous resurrection.

Here rest deposited the earthly remains of

Thomas Stott esq.

Born Hillsborough on 21st June, 1755

He departed this life at his residence in

Dromore

The 22nd day of April, 1829.

In 1825, just four years before his death,

Stott's one and only book of poems "The Songs of Deardra"

was published.

This slim volume, a few poems in decaying

copies of ancient Belfast Newsletters, a worn tombstone, and

a painting hung in Castleward in which the poet and Bishop

Percy are prominent, is all that remains of the poet of

Dromore.

He never attained greatness and remained a

minor poet only. The evidence is that he never strove for

greatness. As he wrote in the title page of the "Songs of

Deardra":

"And if the world should not

prove kind,

As through its mazy paths ye stray,

Be not disheartened - fortune's blind,

And fame oft flatters to betray."

His poetry, even if it were readily

available, would not be much read today. The late 18th

century style is somewhat ponderous, the words pedantic.

Nevertheless, he was a man of his time and as a poet he

recorded what he observed and loved best - the simple

everyday scenes around Dromore and among the meadows beside

the Lagan.

In an age of instant electronic

entertainment it is no longer fashionable to read poetry.

This is a sad passing. A poet, especially a local one, is

also an historian, and the writings of Thomas Stott provide

us with a tangible link with the past.

Whether or not he saw himself as a keeper of

history we'll never know. There is little doubt though that

the urge to record the passing scene was strong. Perhaps, as

a modern poet puts it, "Of the fear of death - the need to

leave messages for those who come after saying, I was there,

I saw it too."

RECOLLECTIONS OF

CHILDHOOD ON A FARM IN CO. DOWN

by MURIEL McVEIGH Biddy was our trap horse.

It was she who was harnessed to our closed trap on every

occasion when travel away from the farm was necessary. She

was a bay with black mane and tail and might have had some

hunter blood in her, since when the Co. Down Staghounds or

the Iveagh Harriers came into the vicinity her ears pricked

up and she was ready to go. Twice a year at

the "screagh" of day Biddy was harnessed into the trap when

my father and the current "girl" set off for Newry Hiring

Fair. Their long day ended after we children had been packed

off to bed excitedly waiting for morning to meet either the

new "girl" or more than once to greet again the one we knew

who had come back to live with us as one of the family for

another six months. This help for my Mother was absolutely

necessary since the woman's role on the farm, as well as

rearing the family, was to milk ten cows twice a day, feed

the pigs - produce of four or five sows - and the calves

besides attending to poultry which entailed collecting eggs,

we children were useful here, setting broody hens to hatch

enough chicks to keep up the stock of Rhode Island Reds,

White Wyandots, Light Sussex, Black or White Leghorns so

that there would always be a good mix of layers and table

birds for the fowlman who called at the farm on a regular

basis. Then there were the big white Aylesbury ducks and

turkeys and geese for Christmas. All these activities had to

be fitted in with the cleaning, cooking daily for up to ten

people, skimming and setting cream to ripen for churning,

butter making and of course dress making and mending. Heigh

ho, farm life was busy.

Biddy

was not solely a driving mare; she had to take her share of

the field work, though being rather skittish the work given

to her was of necessity selective. Acting as part of a team,

harrowing in the grain in spring or even reaping oats was

within her capacity, also I think she may have been chosen

to pull the turnip barrow when the seeds of this rootcrop

were sown in drills. Sharing the stable for many years were

Prince, the reliable bay gelding, strong and capable of

pulling a plough all day teamed up with Jewel, the big shire

mare with the broad back where three or four of us children

were able to ride home from the field after a long potato

digging day. There were some screams and holding on when

Jewel stepped down into the "shough" at the side of the lane

into the yard to have her long drink of fresh water. This

"shough" was there for the sole purpose of watering the

horses and was fed by a little river which came tumbling

down over the stones after flowing between the fields from

the flax dams where the flax was retted in the summer. No

doubt we children found other uses for both the river and

the "shough" though it was out of bounds for horses and

children when the dams were in use for flax. That was a busy

time when the pulled flax had to be carted to the dam and

the beets were neatly stacked in and we children were

allowed to walk all over them to push them down into the

water to be weighted down with heavy stones and big sods

when the water being dammed took over the softening of the

fibres for a week or ten days, after which the dirty work

started and the men with trouser legs rolled up threw the

soggy beets on to the "breugh" to be loaded back on to the

carts and taken to a grass field to be spread out to dry. At

that time the country stank of retted flax though I must

confess to enjoying the smell when the dry flax was

collected and tied into beets with rush bands then stacked

ready to be transported to the mill for scutching. The

lowering of the water in the dam was quite a problem for if

it entered into the larger rivers in bulk it was anything

but conducive to the life of the fish therein, though I

think I am right in saying a day's heavy rain helped to

disperse it. Biddy

was not solely a driving mare; she had to take her share of

the field work, though being rather skittish the work given

to her was of necessity selective. Acting as part of a team,

harrowing in the grain in spring or even reaping oats was

within her capacity, also I think she may have been chosen

to pull the turnip barrow when the seeds of this rootcrop

were sown in drills. Sharing the stable for many years were

Prince, the reliable bay gelding, strong and capable of

pulling a plough all day teamed up with Jewel, the big shire

mare with the broad back where three or four of us children

were able to ride home from the field after a long potato

digging day. There were some screams and holding on when

Jewel stepped down into the "shough" at the side of the lane

into the yard to have her long drink of fresh water. This

"shough" was there for the sole purpose of watering the

horses and was fed by a little river which came tumbling

down over the stones after flowing between the fields from

the flax dams where the flax was retted in the summer. No

doubt we children found other uses for both the river and

the "shough" though it was out of bounds for horses and

children when the dams were in use for flax. That was a busy

time when the pulled flax had to be carted to the dam and

the beets were neatly stacked in and we children were

allowed to walk all over them to push them down into the

water to be weighted down with heavy stones and big sods

when the water being dammed took over the softening of the

fibres for a week or ten days, after which the dirty work

started and the men with trouser legs rolled up threw the

soggy beets on to the "breugh" to be loaded back on to the

carts and taken to a grass field to be spread out to dry. At

that time the country stank of retted flax though I must

confess to enjoying the smell when the dry flax was

collected and tied into beets with rush bands then stacked

ready to be transported to the mill for scutching. The

lowering of the water in the dam was quite a problem for if

it entered into the larger rivers in bulk it was anything

but conducive to the life of the fish therein, though I

think I am right in saying a day's heavy rain helped to

disperse it. Outside school hours there was

always plenty to do and plenty to learn on the farm. The

sheep to be counted every day and in warm showery weather we

had to be specially vigilant to make sure that none of them

became fly-blown; the cows had to be brought in to be

milked; ducks and hens had to be shut in. Perhaps the most

enjoyable chore was helping to take the tea to the field at

harvest time for never did tea taste so good as it did in

the cornfield on a warm August day. In the spring corn had

to be carried to the sower whether he scattered the seed out

of a sheet skilfully draped round one shoulder or with an up

to date fiddle to speed up the process. On

rare occasions there was the reward of being loaded up into

the trap behind Biddy and going off to spend the day with

our grandparents who lived ten miles away. Then Biddy

stepped out smartly, trotting on the level and being helped

up the hills when those of us who could got out to stretch

our legs. We were shown many interesting things on the way

like the big water wheel which drove a mill somewhere near

Katesbidge or the farmhouse which had houseleek growing on

its roof or the bank where the dainty little blue harebells

grew and once we were delighted to be passing Magheral

Chapel when the bell was ringing the call to worship. Biddy never lost her fear of motors of any kind and when she

met one her instinct was to turn tail and run which but for

the quick reaction of my Father almost brought us to grief

more than once. Notably one thirteenth of July when we had

spent the day in Newcastle and were on our way home in a

downpour; suddenly round a corner came an charabanc, with

umbrellas along the sides and the passengers singing,

probably on their way home from Scarva. Well poor terrified

Biddy went up on her hind legs and turned right round on the

road and it was only the speed with which my Father reached

her head to soothe her that saved the lot of us.

I am afraid I have no recollection of what became of Biddy

for at the ripe old age of nine I learned to ride a bicycle

and from then on lost interest in horses. What happy days we

had growing up on the farm.

SOME DROMORE CLOCKMAKERS

by WILL PATTERSON In years gone by a number

of clockmakers plied their trade in Dromore. Research has

produced the following names of those who worked in the

town. Samuel Bailie had his business in

Dromore from 1765 to 1785. He made fine grandfather clocks

with brass dials. He numbered his clocks on the dials. Some

of his clocks are still around the Dromore area and

elsewhere. There were Bailies from Dromore who went to

Downpatrick and worked as clockmakers there. In fact there

are brass dial clocks marked 'Bailie of Down' which were

made by Bailie of Downpatrick. There was a

family called Cherry who were clockmakers in Dromore in the

eighteen hundreds. Clockmakers of the same name also worked

in Lurgan and Banbridge at this time. Indeed one was in

business as far afield as Philadelphia in 1849.

In the early 1800's a clockmaker named Crozier was active in

Newry and a James Crozier was in business in Dromore in

1854.

Scott (Christian name unknown) was at work in Dromore in the

late eighteenth/early nineteenth century.

David Sterling was a clockmaker in 1854.

Robert Sterling was in the town in 1865, but later moved to

Banbridge. George Arlow produced clocks in

the town from 1865 to 1868. They were white dialed with

mahogany cases. It is known that considerable number of

these still exist around the locality.

Another clockmaker family from the Dromore and Banbridge

area were the Nelsons. Some of their products still exist

around this area. J. & R. Nelson were in

Dromore from 1825 to 1835. Joseph and Robert

from 1846 to 1859. Robert Nelson (1) from

1825 to 1846. Some of the Nelsons went to New

York, where they founded a very successful clock and watch

business. It would be of interest to learn if

anyone in the vicinity have in their possession any examples

of the aforementioned craftsmen's work.

|