|

ROBERT BURNS AND

THE LAST HARPBY SAM JOHNSTON |

|

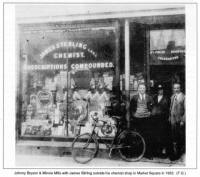

To a whole generation of Dromore folk the

name Robert Burns does not immediately suggest the immortal

Ayreshire bard.

Instead it conjures up in the mind's eye a

small man in a flat cap and well-worn showerproof who was

once as much a landmark in the Market Square as the Town

Hall, which had been build by his father many years ago.

Robert, who was feeble-minded, appar ently having no living

relatives, was well cared for by a lady in Meeting Street

who saw to all his needs. He spent most of his time

meandering slowly around the town where he seemed to enjoy

the daily excitement of the town Square. Over the years he

gradually became one of Dromore's best known and much loved

characters, with his Chaplin-esque walk, wide grin and his

greeting of "Hi-ye King William?" to every male he

encountered.

Robert

was not averse to indulging in a little begging by asking

for a "harp" which was his name for a penny. At one time

this coin bore the replica of an Irish harp on it's reverse

side. When asked to choose from a handful of proffered coins

he would ignore the silver coins of anykind, thinking them

to be of less value than his "harp". Robert

was not averse to indulging in a little begging by asking

for a "harp" which was his name for a penny. At one time

this coin bore the replica of an Irish harp on it's reverse

side. When asked to choose from a handful of proffered coins

he would ignore the silver coins of anykind, thinking them

to be of less value than his "harp".

Robert was generally quiet and inoffensive.

Although it was soon discovered that certain words or

phrases would have the effect of arousing in him quite an

inexplicable fury and rage. Sadly, human nature being what

it is, there were those who's perverted idea of fun led

them to ignite this reaction in him before moving away,

leaving him swearing loudly to himself. Much to the

bewilderment and consternation of innocent by-standers.

Around about the 1950's Robert Burns died

and the Rev. Kilpatrick in announcing his funeral in the

Cathedral, expressed the hope that many would pay their last

respects to the old man by attending. In the event a vast

multitude followed the cortege to his last resting place in

the churchyard. So great was the concourse that a stranger

could have been forgiven for presuming that some person of

great distinction was being interred.

As I sat in the church, before and during the burial

service, my mind was full of thoughts of this old man I had

known so well. There came, unbidden, into my mind the

following lines in a metre I had never used before. A

ready-made epitaph for this fellow townsman who had found

fame in his own humble way.

| |

"You know old Robert Burns?"

Well, Robert's dead!"

"That old man of queer turns?"

"Yes. Robert's dead."

And all those folk who tempted Robert sore

Their shameful tricks will play on him no more,

For Robert's dead. |

|

| |

For pennies he would plead,

"Give me a harp".

His was a trivial need,

"Give me a harp".

And daily as he shuffled through the town,

He would'nt take your "bob" or "half-a-crown".

"Give me a harp". |

| |

I like to think he'll

get

To Heaven's gate.

I think that he'll be met

At Heaven's gate

And bidden "welcome! come and meet your kin,

You've naught to fear, fools cannot err herein

-----------------and here's a harp!" |

|

CHAT

LINES - yarns from the Station yard

as told to me by a former porter at Dromore Station.

BY ROSEMARY McMILLAN

I started at Ashfield Halt in 1943, as a boy

porter. I suppose I was about maybe sixteen then. A vacancy

occurred in Dromore and I got down in there before I was

twenty.

The Station Master in those days was R. H.

W. Reevy - he was very regimented of course - he talked very

quick! There were usually two clerks, a chappie called Mason

and another one was Frank Boal. There were three signalmen,

John Fallon, Bob Eliot and Fred Savage.

In 1943 I earned a pound a week and of that,

4d went to the pension and if I had went on according to

plan, I w ould

have got ten shillings aweek when I retired. In those days

ten bob was a decent pension because a ploughman was getting

twelve and six for working! In fact, old railwaymen, you

would have thought, should have been much sought after!

There was a steam crane man and that was a highly

specialised job, he could lift things and set them down,

like he was using a knife and fork. He only got seven

shillings and sixpence a week of a pension when he retired. ould

have got ten shillings aweek when I retired. In those days

ten bob was a decent pension because a ploughman was getting

twelve and six for working! In fact, old railwaymen, you

would have thought, should have been much sought after!

There was a steam crane man and that was a highly

specialised job, he could lift things and set them down,

like he was using a knife and fork. He only got seven

shillings and sixpence a week of a pension when he retired.

The wages were paid in shillings and pence.

If say, you had to get five pounds, well that was a hundred

shillings. They didn't mention pounds at all, because I

suppose you see, the wages were so small. This happened up

to about twenty-five years ago. The late Brian McConnell M.P.

expressed his amazement at this "In the name of goodness",

he says to me, "they're not still at that auld game are

they?" We were paid on a Thursday, which was unique, and

there was a time when we were only paid once a fortnight!

And when you joined the railway, you didn't have to have an

unemployment thing and a sickness one. You only had the

sickness benefit because you would never be unemployed on

the railway. It was like joining the army nearly.

I was never on the Bureau in my life. I went

to Dromore, to the Town Hall, and got my Bureau card and and

handed it in. The only time I was ever back in the Bureau

office was in Lisburn. There was a dispute on and they had

laid us off. I promptly went to my local Social Security

office, and the girl asked me when I was there last and I

said, "I was never here before but I was in the one in

Dromore in 1943!" And in fact, that was in July of that

year, and I have a letter there from them, saying that the

adjudicator had looked at my case, and had decided that I

wasn't entitled to any money, because I wasn't unemployed -

I was just laid off- or something to that effect. But, it

took from July to September to tell me that, so I'd have

been hungry, if I had of needed money!

Starting times at Banbridge were 4 a.m. if

you were signalman and 4.30 a.m. if you were shunting. I

remember when I was living at Mullafernaghan; at that time

there was a guard on the train called Ned O'Hagen. When he

heard I lived at Mullafernaghan he says, "Sure we'll pick

you up and bring you up (to Banbridge). You needn't ride the

bicycle away up here." I thought that was a good job, but

next morning I was wakened by him coming shouting round the

house, "Are you going to lie all day?" It was about a

quarter to four in the morning. That was the morning I slept

in. I very rarely slept in. You were normally rostered for

eight hours but you could be asked to do another four hours

for which you were given so many hours notice, unless there

was an emergency.

You were paid time and a quarter for

overtime work between six in the morning and ten at night.

If you were on night duty you got time and a quarter from

ten o'clock at night to six in the morning. If you were on

overtime during those hours you got time and a half. You got

time and a half on a Sunday. Eventually there was a double

time on a Sunday. Then we got British rates and they put it

back to time and three-quarters for a Sunday and to this day

it is time and three-quarters except for P-way men

(menders!) they get double time. There used to be a saying

that, when railwaymen went to church, they had to take a

piece of bread for the Sexton's dog - for he didn't know

them.

The uniform came with the job and of course

it was in various grades. The travelling ticket collectors,

they were usually measured by two tailors who came over from

England. You were measured on the spot. In the case of the

Banbridge line you would have been notified that the tailor

was going to be on the train, on such and such a day, and

the Station Master had to have all staff on the platform to

get their measurement done. There is a story that, one day

when the Enterprise (Dublin Express) was going through

Lisburn this man says, "Oh look, there's somebody lookin

out" and this fellow replied "Yes, that's the railway

tailor, he's measuring us!" Some of the uniforms they sent

out were terrible, not the right size at all. Bob Eliot got

a form for measurements for an overcoat. In those days they

were a big heavy overcoat and they were puce, a sort of

purply colour - a terrible lookin thing! But Bob, he thought

they were the greatest thing at all for putting over the bed

in the winter-time. So he got me to measure him in the

cabin. "Put plenty of length on it," he says - so I, of

course, put it away down near his ankles, and it just came

back the normal size.

Bob had a funny way of saying things. One

day, he was leaning over the handrail of the signal box,

puffing away at his pipe and he observed "I see there's

going to be another concert the night agin" "What d'ye

mean?" I says. He says "I see an auld fella there (a tomcat)

goin' round puttin' up the posters!"

The railway carried all the general

merchandise for the shops - jams and all the different

grocery stuff. There was a lot of meal and fertiliser.

Fertiliser was a big thing. I think it was carried very,

very cheaply and then it was stored there at the station. In

fact, the late Francis Russell was the biggest merchant for

that fertiliser in those days. Tucker Thompson and - Gamble,

they were sent up to help us store the stuff. It was taken

out of the wagons and piled up about twenty bags high in the

store. And those boys were tough. Bear in mind they were two

hundredweight bags at that time. They had a barrel, so the

two of them set the bag on the barrel - then one of them put

the bag on his back and walked up the stack to the very top

- dumped it and came back down again. Och, it was hard work.

There was a lot of coal brought in. There

was a Murphy about Dromore in the dim dark days. He had an

office beside the Rectory, if I remember right. There was

bad coal at one time and somebody gathered up a lot of

stones and set a sign on it "Murphy's Coal!" Tom Carlisle,

was the last one to get coal at Dromore Station. He also

done the cartin' down to the town and old Bob McIlrath, I

think was the man who drove the horse. That big black horse

went on until he died of pneumonia or something. After that

goods were taken up and down in Tom Carlisle's coal lorry.

During the war there was a heap of coal behind the store. It

was piled up by German prisoners of war and painted white so

that if any was stolen it would show up.

Of course all the bread came that way -

McCombs, Barney Hughes and Inglis. Inglis bread went into

Princes Street to an agent that Davy Wilkinson and all them

worked for.

Loads of spuds were sent out on the trains

and it was usual for the farmer to tip the porter who loaded

his crop onto the train. One farmer who was remiss about

this was seen searching for something on the platform,

whereupon it was duly remarked "Mister, if your'e lookin'

for your purse ye didna loss it about here!"

There were certain things I would never

forget. Like, I remember one morning when I lived in what

was known as the Moss Loanin and I was riding to Ashfield

Halt to start at a quarter past six. It was during the

blackout. The blackout suited me well for my battery lamp

was very poor anyway - so I was keepin within the rules - in

a sense! There was a kind of dampness in the road and

sometimes I would have come on the B men. On occasion, they

would have stopped me but eventually they got to know me and

might even have said "Good morning" when I was going past.

But, this particular morning, with the B's shadow on the

road and with my poor light, now and again I slowed up,

because you would have thought there was something there ye

see. I turned off the main road onto the Ashfield road at

Mullen's Corner and this particular shape became so real

that I put my hand out. It materialised into a horse - boys

the hairs stood on the back of my neck and I went off the

bicycle. It must have kicked out but I was very fortunate I

only got a stay of the mudguard broken.

It

was all steam trains in those days. I remember the first

diesels on the Banbridge line. In fact, the GNR pioneered

diesels. A Dromore man was actually in the middle of that -

a Mister Hobart. He wanted Harland and Wolff to have a

separate laboratory for diesel traction, because, he said

they were foremost and had the railway more or less at their

disposal for trying them out. There is one of the old GNR

diesels in the Isle of Man. It

was all steam trains in those days. I remember the first

diesels on the Banbridge line. In fact, the GNR pioneered

diesels. A Dromore man was actually in the middle of that -

a Mister Hobart. He wanted Harland and Wolff to have a

separate laboratory for diesel traction, because, he said

they were foremost and had the railway more or less at their

disposal for trying them out. There is one of the old GNR

diesels in the Isle of Man.

When I was a ticket collector at Banbridge,

an American arrived lookin for the train for Dublin. At that

time there was a wee diesel, some of them called it the "Dinkie",

which made the connection between Banbridge and Scarva for

the Dublin train, but when it had to be serviced, there was

only one ye see, it was replaced by a small B engine and one

coach. So, when this small engine and one coach came in the

American said to me, "You did say I would get the Dublin

connection here?" I says "Yes, that's right, that's it now".

He took one look and said, "I guess I'll take one of those

home to the kids!"

I was transferred the year we got the prize

for the best kept station. Old Bob Eliot, smokin' the pipe

as usual,

he

said "Ye know, yez wouldn'tlisten to me when I was tellin

yez about these flowers". Ye know they sent seeds and all

for it, and we put in a lot of work makin' beds ye see. He

said, "The company could see yez were doin' nothing when yez

don all that work. I told yez at the start, when yez got the

cheque that was when they were soapin' yez now they have

started to shave yez!" So they transferred me to Lisburn! he

said "Ye know, yez wouldn'tlisten to me when I was tellin

yez about these flowers". Ye know they sent seeds and all

for it, and we put in a lot of work makin' beds ye see. He

said, "The company could see yez were doin' nothing when yez

don all that work. I told yez at the start, when yez got the

cheque that was when they were soapin' yez now they have

started to shave yez!" So they transferred me to Lisburn!

It was a good old job. I worked for them for

forty seven years and they never caught me on yet!

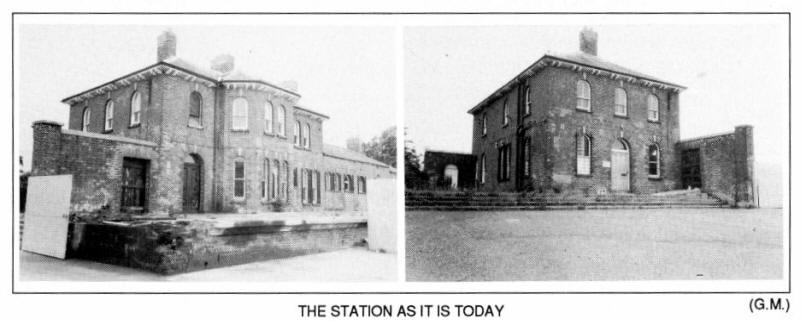

The Ulster Railway Co. gave financial

encouragement to other smaller companies - one of which was

the Banbridge, Lisburn and Belfast Co. The line was opened

on July 13th, 1863. It was fifteen miles long and branched

South from Knockmore Junction. Like many other lines it fell

to the Beeching axe in 1956.

MEMORIES

OF EARLY SCHOOLDAYS

BY MURIEL McVEIGH

There it stands almost unchanged since 1915

when I stumbled over its doorstep at the bright old age of

four, the building that was then known as Garvaghy National

School, just one of hundreds perhaps thousands such

erections put there by the churches throughout this our

"land of saints and scholars". Someone with more pretensions

to historical know-ledge than I will be able to date these

buildings of which not too many, I imagine, remain

materially unchanged over the years as this one.

It

was the centre of my life for the next decade, and so many

memories crowd each other out that I am finding it hard to

focus on any one. There were those frosty mornings when we

chased each other along the road to get to break the ice

that had formed in the potholes during the night, the stove

in school had not been lit long enough to destroy Jack

Frost's artistry on all the school windows and the remains

of yesterday's drinking water in the bucket in the school

porch had a lovely coating of ice to be lifted out and

thrown at any convenient target by those on their way to the

well to fetch water for today's consumption. Delight when

snow had fallen to enable slides to grow from school gate to

church gate ably produced by the hobnails in the `big' boy's

boots while the smaller children had their own private slide

to help each other negotiate without falling in the little

playground inside the gate. Traffic on the road was not a

problem since bicycles had bells and farm carts had noisy

iron-shod wheels. It

was the centre of my life for the next decade, and so many

memories crowd each other out that I am finding it hard to

focus on any one. There were those frosty mornings when we

chased each other along the road to get to break the ice

that had formed in the potholes during the night, the stove

in school had not been lit long enough to destroy Jack

Frost's artistry on all the school windows and the remains

of yesterday's drinking water in the bucket in the school

porch had a lovely coating of ice to be lifted out and

thrown at any convenient target by those on their way to the

well to fetch water for today's consumption. Delight when

snow had fallen to enable slides to grow from school gate to

church gate ably produced by the hobnails in the `big' boy's

boots while the smaller children had their own private slide

to help each other negotiate without falling in the little

playground inside the gate. Traffic on the road was not a

problem since bicycles had bells and farm carts had noisy

iron-shod wheels.

On occasional rainy days the porch reeked of

wet overcoats and caps and it was a comfort to gather round

the stove to get stockings dried before the serious day's

work began with religious instruction, as stated on the card

hanging by the door. This card was carefully turned at the

end of the half-hour to proclaim to anyone who came in that

secular instruction was now the order of the day. Those were

the days when the lunches, mostly consisting of soda bread

and butter washed down by fresh sweet milk out of a bottle

carried in the satchels of sixty or so noisy children had to

be consumed inside the building during the half-hour

allocated to `playtime' no peace for the teachers on those

day's, fortunately few.

Spring never failed to provide us with so

many new experiences, new leaves to enable us to identify

all the trees in the locality, new flowers to be found in the hedgerows and recorded in the nature study

book which hung on the wall, bird's nests to be found and

the variety of size and colour of eggs learnt and most of

all winter boots or clogs discarded when bare feet were

again in evidence and toes were `crigged' or scuffled along

the dust at the sides of the roads. What a relief it must

have been to the ears of the teachers not to have to put up

with the noise of studded boots or shod clogs on wooden

floors.

be found in the hedgerows and recorded in the nature study

book which hung on the wall, bird's nests to be found and

the variety of size and colour of eggs learnt and most of

all winter boots or clogs discarded when bare feet were

again in evidence and toes were `crigged' or scuffled along

the dust at the sides of the roads. What a relief it must

have been to the ears of the teachers not to have to put up

with the noise of studded boots or shod clogs on wooden

floors.

In school as well as introducing us to

cursive handwriting, transcription, dictation, composition,

analysing, parsing, parts of speech, literature, poetry,

geography, history, multiplication and division tables and

application, decimals, fractions and such mathematical exer

cises even up to stocks and shares Miss Clinton presented us

with the rudiments of science viz. properties of gases like

oxygen and carbon dioxide, astronomy as in the movements of

earth and moon in relation to sun causing seasons and day

and night and particularly natural history I can still

remember the thrill of learning about dicotyledons and

monocotyledons.

When we reached the senior classes we donned

our white aprons and learnt to bake bread and scones, cook

dinners such as Irish stew and a favourite of mine to this

day boiled bacon and cabbage. We even had lessons on how to

keep certain household artifacts clean. It was a red letter

day when I took our halldoor brass knocker to school to

learn how to keep it shining and bright though I must

confess that I've forgotten most of the commodities that we

used like the powder we called whitening, bath brick and

black lead for the stove. Well, household maintenance was

never my forte.

Perhaps more important were the incidental

lessons of behaviour when we learned to get along with our

neighbours by being tolerant, forgiving, truthful, observing

others right to privacy and respecting other people's

property, lessons not always easy to learn. Of course we had

our disagreements over which we fought with whatever weapons

were available as fists for the boys, words by those able to

use them and even hair pulling shame! Yes, shame was

instilled in us too. I can hear the admonition 'you ought to

be ashamed of yourself coming at me over the years and I am

sure it deterred many of us from indulging recklessly in

unacceptable behaviour.

Yes, there stands the building now used as a

church hall where hundreds of children spent their early

years willingly or otherwise, a monument to those who went

on to live out their lives all over the world and adjusted

to fit into whatever environment fate placed them.

HORSES KILLED BY

LIGHTNING

BY TREVOR MARTIN

The Irish News of 28th May, 1920 contains

the following story in connection with Dromore.

"During a violent thunderstorm over

Dromore and district on Wednesday evening, a farmer, Robert

Thompson, of Islanderry, and his nephew, a young man named

Walter Arlow were struck down by lightning. Two horses,

valued about 100 pounds, with which they were working at

potatoes, were killed instantaneously.

Arlow

was the first to recover from the shock, and on coming to,

succeeded in calling help and having Thompson removed home.

Dr. Carlisle was quickly in attendance and it is stated

that, although partially paralysed, the patient will

eventually recover. Arlow says that his forehead was

scorched, and that when he recovered consciousness, he

noticed that the dead horses appeared to be enveloped in a

blue smoke, and that a heavy odour exuded from their bodies. Arlow

was the first to recover from the shock, and on coming to,

succeeded in calling help and having Thompson removed home.

Dr. Carlisle was quickly in attendance and it is stated

that, although partially paralysed, the patient will

eventually recover. Arlow says that his forehead was

scorched, and that when he recovered consciousness, he

noticed that the dead horses appeared to be enveloped in a

blue smoke, and that a heavy odour exuded from their bodies.

The rainfall which followed the

thunderstorm was the most extraordinary ever known in the

locality. Few of the local water channels were able to

contain it, with the result that many parts of the town were

flooded."

Lightning is caused when there is a

discharge of electricity either between clouds or between

clouds and the earth. Although most lightning storms pass

peacefully there have been many fatalities. In Zimbabwe in

1972 a bolt of lightning hit a building killing 25 people.

The injuries caused by lightning can be varied depending on

the severity of the strike. What actually happens is that

the body is subjected to an electrical discharge which

interferes with the body's own electrical system. In severe

cases this is so great that the heart will stop altogether,

it additionally can cause the skin to be burned to a

significant degree.

Intrigued by this I set out to find out some

more information and indeed to see if anyone could recall

either of the two gentlemen concerned. We contacted a

president of Islanderry who was able to supply us with the

following information.

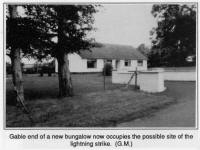

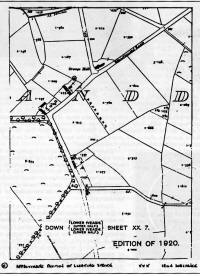

There was a seam of an iron substance

contained in the ground at least 500 yards long that emerges

to the surface in various locations in the area. The map

shown on the opposing page gives you an idea of the extent

of the iron area and also shows the spot where both men were

struck.

My informant cites several places where this

seam surfaces near his hedgerows pointing to the fact that

lightning h ad

struck those places burning his hedges out. He also recalled

that Robert Thompson was using an iron plough and that the

harnesses of the horses also contained a great deal of iron. ad

struck those places burning his hedges out. He also recalled

that Robert Thompson was using an iron plough and that the

harnesses of the horses also contained a great deal of iron.

The lightning struck the plough killing both

horses and running up the handles of the plough injuring

Robert Thompson. Young Arlow who was in the vicinity was hit

by the force of the strike but was able to summon help to

get Robert to hospital.

He spent some time in hospital recovering

from his ordeal and the marks of the strike on his body, two

blue almost bruise like marks the size of a farthing were

with him until the day he died. The psychological effects

also stayed with him throughout his life and he could tell

of the onset of thunder storms, hiding in the corner of the

room with his eyes closed until they had passed overhead.

An interesting aside was that after being

struck by lightning Robert developed the power to divine

water saying that he could feel it under his feet. He was

much in demand in the area and his skill developed to such

an extent that he could tell the depth of water when using a

divining rod.

|