|

WATER

by John McGrehan

During the past months there has been great activity in

the town with the laying of new water mains and although

traffic has been subject to some disruption, yet with the use of present day

machinery the work has been carried out very quickly.

to some disruption, yet with the use of present day

machinery the work has been carried out very quickly.

When the original water scheme was completed nearly 70

years ago, with the laying of cast iron mains, the work was

done mainly by manual labour and it took the contractor,

Grainger Bros. of Holywood, much " longer to complete the

scheme in comparison. In the original scheme, which was

carried out to the order of Dromore Urban Council, the water

supply was extracted from a stream which started on one of

the Dromara mountains. A reservoir to assist in conserving

this supply of water was erected at the top of Bankhead's

Hill. This scheme provided for the erection of fountains off

the water main in different places in each street in the

town, from which people were able to draw water and carry it

home.

However,

it was not long until it became evident that this scheme was

proving insufficient to meet the needs of the town and

during the summer it was common for the supply of water to

be turned off at night, so that it could gather sufficiently

to satisfy people's requirements when turned on again the

next day. Since that time, Dromore had joined the Portadown

& Banbridge Regional Joint Water Board and with the erection

of different dams and the construction of new trunk lines we

were assured of an adequate supply of water at all times. However,

it was not long until it became evident that this scheme was

proving insufficient to meet the needs of the town and

during the summer it was common for the supply of water to

be turned off at night, so that it could gather sufficiently

to satisfy people's requirements when turned on again the

next day. Since that time, Dromore had joined the Portadown

& Banbridge Regional Joint Water Board and with the erection

of different dams and the construction of new trunk lines we

were assured of an adequate supply of water at all times.

While we appreciate how convenient it is today to just go

over to the tap and get as much water as we want, it is well

to reflect on how we got our water before these schemes came

into being.

In

the Square opposite Messers Neeson's shop just outside the

low wall which once enclosed the Market Yard, there stood a

pump which always had a plentiful supply of water at all

times throughout the year. There was also a granite drinking

trough at this pump which served the purpose of providing

drinking facilities for horses. As a matter of interest, it

is pleasing to see that this pump, together with the trough,

has been preserved and erected within the Market Square on

the opposite side of the Town Hall from it's original

position. In

the Square opposite Messers Neeson's shop just outside the

low wall which once enclosed the Market Yard, there stood a

pump which always had a plentiful supply of water at all

times throughout the year. There was also a granite drinking

trough at this pump which served the purpose of providing

drinking facilities for horses. As a matter of interest, it

is pleasing to see that this pump, together with the trough,

has been preserved and erected within the Market Square on

the opposite side of the Town Hall from it's original

position.

In Meeting Street there was also a good pump, the same

style as the one in the Square, which provided a bountiful

supply of good cold spring water and no matter how warm and

dry the weather was in the Summer we were always assured of

a good supply of water. This pump was erected about a

quarter of the way up Meeting Street hill and was nearly in

the centre of the road.

While this pump gave great service, if the wheels were

not regularly oiled, when it was being used it made a

screeching noise which was very disturbing, especially late

at night or early in the morning. Brewery Lane also had a

pump, but during the summer it was not reliable as the

spring would dry up and you could not get any water. At the

back of a house convenient to this pump there was another

pump from which you could get water, but to get to this pump

you had to go through a blacksmith's shop and when there was

a good number of horses waiting to be shod it was not a

pleasant task going past these animals! Rampart Street too,

had a pump which served the needs of the people in that

locality. Up in that direction there was also a pump up at

Barban Hill. The pump in Church Street was situated at the

bottom of very steep steps and it was not too handy to carry

full cans or buckets back up these. Mount Street, Gallows

Street and Cross Lane each had their pumps and some people

had quite a distance to carry the water for their daily

requirements. As one lady observed, "You made a can of water

last a long time!"

There

was a pump in Weir's Row and some people from Princes Street

carried water from it as they preferred this source of

supply. Outside the town there were also pumps at Holm

Terrace but there were two well known pumps: one was at the

top of Circular Road, Known as Peggy's pump and the other at

Drumbroneth, known as Cherry's pump. Peggy's pump was

situated a short distance from the road and sometimes as you

went to get water, you had to take the top off the pump and

put some water in to get the pump started. The pump in

Drumbroneth took it's name from a family who lived in it's

vicinity. There

was a pump in Weir's Row and some people from Princes Street

carried water from it as they preferred this source of

supply. Outside the town there were also pumps at Holm

Terrace but there were two well known pumps: one was at the

top of Circular Road, Known as Peggy's pump and the other at

Drumbroneth, known as Cherry's pump. Peggy's pump was

situated a short distance from the road and sometimes as you

went to get water, you had to take the top off the pump and

put some water in to get the pump started. The pump in

Drumbroneth took it's name from a family who lived in it's

vicinity.

There were also a large number of spring wells from which

people drew their drinking water without the assistance of a

pump. There were two of these which were , better known than

the others. One in Ballynaris called Bishop's Well and the

other known as the Fairy Well. The Fairy Well was situated

in a field belonging to Caughey. Brothers at the side of the

Weir's Stone. This well was known to many locally and people

came from a distance to get water from it as they felt it

tasted better.

For washing some people liked to obtain soft water, so

they placed a barrel at the end of the down pipe and

collected the rain water from the roof for this purpose.

In those days it was a common sight to see a person

carrying two buckets full of water, with a hoop between them

to keep the water from spilling round them.

| FOUNTAINS: |

|

(a) were used as a method of

drawing water, by the simple turning of a knob, from

the piped main water supply system |

| PUMPS: |

|

were used to raise water from

various spring wells prior to the introduction of a

piped mains supply. This was by the laborious up and

down action of the handle (b) or by manually turning

the handle in a circular motion (c). |

| |

|

|

THE LIFE AND TIMES OF

JAMES KIRKER STRAIN

By Harold Gibson

The

name of James Kirker Strain is virtually unknown in Dromore

and district today yet he spent some 48 years living in the

town and was the minister of First Dromore Presbyterian

Church from 1863 until 1907 having been assistant to the

Rev. James Collins from his ordination in First Dromore in

1860. After the death of Mr. Collins in 1863 Mr. Strain

became the Minister in full charge. The

name of James Kirker Strain is virtually unknown in Dromore

and district today yet he spent some 48 years living in the

town and was the minister of First Dromore Presbyterian

Church from 1863 until 1907 having been assistant to the

Rev. James Collins from his ordination in First Dromore in

1860. After the death of Mr. Collins in 1863 Mr. Strain

became the Minister in full charge.

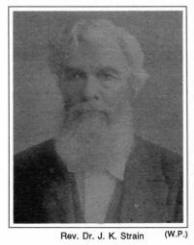

James Kirker Strain was born on June 19th 1834 and was

the son of the Rev. Alexander Strain who was minister of the

Presbyterian Church at Cremore, near Tyrones Ditches in

County Armagh. Rev. Dr. J. K. Strain M.P.) The days in which

he lived were difficult times both socially and politically.

Little is known about his early days but as a student he

achieved academic distinction and he graduated from Queen's

College in 1856 with a Bachelor of Arts degree. Strain was a

brilliant pupil and records show that he carried off many

prizes both at Queen's and at Assemblys College. His

brilliance did not leave him in later years as he was

awarded a Doctorate in Law from the Royal University of

Ireland in 1885.

Great things were happening in the life of the church at

this time. Revival had been sweeping across America and the

effects of this revival continued into 1859 moving into

Wales, Ireland and Scotland. Dromore, whilst not directly

affected by the revival did witness a marked increase in

church attendance and an increase in the number of prayer

meetings in the district. It was in such a heightened time

of spiritual awareness that James Kirker Strain came to

Dromore. An account in the News Letter dated Saturday, 10th

September, 1859 tells of an open air service being held on

Sunday, 4th September, 1859 in a field belonging to Mr. John

McDade, convenient to the town. "There were present at least

1000 persons, comprised of the middle and respectable

inhabitants of the town and surrounding district".

Mr. Strain first preached in First Dromore on 4th

December, 1859. He was one of a number of men to preach with

a view to receiving a

call

to the church. On hearing him preach Thomas Jamison records

in his diary "He is clever". However the congregation issued

a call to another candidate, Mr. Boyle, on the 14th

December, 1859. Mr. Boyle declined the call the next day and

on 22nd January, 1860 Mr. Strain was back again in the

pulpit of First Dromore and in the words of Mr. Jamison "he

preached a most impressive sermon" using as his text "Herein

is love, not that we loved God, but that he loved us and

sent His Son to be the propitiation for our sins." Mr.

Strain again conducted evening worship and preached from the

text "What must I do to be saved." Mr. Jamison recorded that

this was the most touching sermon that he ever heard. Mr.

Strain was not the only nominee for the vacancy as a poll

taken in the congregation on the 29th January shows. Two

other men, Mr. Anderson and Mr. Arnold each received 1 vote

but Mr. Strain received 73 votes. On the 7th February, 1860

Mr. Anderson and Mr. Jamison presented a call to Mr. Strain

at a meeting of the Belfast Presbytery. Mr. Strain accepted

the call at once and so his ordination took place on 27th

March, 1860 in the presence of a large congregation in First

Dromore Church. call

to the church. On hearing him preach Thomas Jamison records

in his diary "He is clever". However the congregation issued

a call to another candidate, Mr. Boyle, on the 14th

December, 1859. Mr. Boyle declined the call the next day and

on 22nd January, 1860 Mr. Strain was back again in the

pulpit of First Dromore and in the words of Mr. Jamison "he

preached a most impressive sermon" using as his text "Herein

is love, not that we loved God, but that he loved us and

sent His Son to be the propitiation for our sins." Mr.

Strain again conducted evening worship and preached from the

text "What must I do to be saved." Mr. Jamison recorded that

this was the most touching sermon that he ever heard. Mr.

Strain was not the only nominee for the vacancy as a poll

taken in the congregation on the 29th January shows. Two

other men, Mr. Anderson and Mr. Arnold each received 1 vote

but Mr. Strain received 73 votes. On the 7th February, 1860

Mr. Anderson and Mr. Jamison presented a call to Mr. Strain

at a meeting of the Belfast Presbytery. Mr. Strain accepted

the call at once and so his ordination took place on 27th

March, 1860 in the presence of a large congregation in First

Dromore Church.

As we have already mentioned he came as assistant to the

Rev. Collins and spent those first three years under the

guidance and influence of his senior. At this time Mr.

Collins lived in Parkrow House while it appeared that Mr.

Strain lived in rented accommodation in the town. Mr. Strain

appeared to settle in to his new surroundings fairly

quickly. Notes from Mr. Jamison tell of his sermons often

accompanied by comments such as "this was one of the best

sermons." The times in which he lived were marked by large

attendances at public worship and by large numbers of pupils

attending Sabbath school. For example, a prayer meeting held

in Belfast on 2nd July, 1860 saw an attendance of around

20,000 people. This was one of many such gatherings that was

held in the aftermath of the Revival and the Belfast

meetings usually took place in Botanic Gardens. On July

12th, 1860 a social was held at which 310 Sunday school

pupils had tea and Mr. Strain was presented with a preaching

gown. On 2nd September, 1860 Mr. Strain preached to an

immense congregation on the subject "The Signs of the Times"

and the offering amounted to �6:10:0d.

Ireland was still recovering from the Potato Famine and

all the consequences that had come upon the land were still

keenly felt. Industry in Dromore was mainly hand loom

weaving much of it being done in the homes. Ship building

had just begun in Belfast a few years earlier and so the

industrial future of Ireland was beginning to take shape.

During Strain's ministry in Dromore much political change

was attempted with Gladstone seeking to introduce Home Rule

for Ireland. "My mission is to pacify Ireland," Gladstone

remarked as he set off for Windsor to be accepted by Queen

Victoria as her Prime Minister. These were also days of

political uncertainty and the "Irish question" still

dominant. It was in such days that James Kirker Strain lived

and ministered among the people of Dromore. In 1881 the

population of Dromore was given as 2491 and it is reported

that the previous 15 years had witnessed a great change for

the better at Dromore.

Queen Victoria was reigning the Empire so Victorian

values and standards were very much to the fore.

A Visit to

America

Travel

was somewhat slower than it is today and given the account

of Strain's visit to America he tells us that he left

Dromore on 26th July, 1870 at 11.00 a.m. and eventually

arrived in New York on Monday, 8th August, 1870 though he

did not get off the ship until the next day due to custom

house arrangements. It would appear that the reason Mr.

Strain visited America was in order to raise funds for the

building of a new manse. Parkrow House, where Collins had

lived was not the property of the church. Mr. Strain

undertook some preaching and gave lectures while in the

States one of which was entitled "Happy Homes" and he tells

us that there was a good attendance and the collection

"amounted to the magnificent sum of $13:50c". On the Sabbath

3rd September he preached in Third United Presbyterian

Church in Pittsburg after which he went West to Petersburg

in Illinois before returning to the East and visiting

Philadelphia, Baltimore, Princeton, Albany, Troy,

Kinderhook, Newburg, New York, Brooklyn, Jersey City and

many other places. He also went to Toronto and gives us an

account of seeing the Niagara Falls. His was one of

temporary disappointment and as he records, "The longer one

looked at them the more awful and awe-inspiring they

became". He was a man who enjoyed good preaching and in his

little book he tells of the various preachers he heard. Some

he heard gladly and others he described as being profane in

their handling of the text. He was a man with a great sense

of humour as is shown when he tells of falling asleep while

listening to one preacher. He says "I fell asleep actually

with my eyes open- a new plan which I would recommend to all

sleepers in church!" On his last Sunday in America, the 6th

November, 1870 he preached in 7th Avenue UP Church in New

York at 10.30 a.m. He went to church in the afternoon and

again in the evening and heard two other preachers, one whom

he described as good and the other as no preacher at all! Travel

was somewhat slower than it is today and given the account

of Strain's visit to America he tells us that he left

Dromore on 26th July, 1870 at 11.00 a.m. and eventually

arrived in New York on Monday, 8th August, 1870 though he

did not get off the ship until the next day due to custom

house arrangements. It would appear that the reason Mr.

Strain visited America was in order to raise funds for the

building of a new manse. Parkrow House, where Collins had

lived was not the property of the church. Mr. Strain

undertook some preaching and gave lectures while in the

States one of which was entitled "Happy Homes" and he tells

us that there was a good attendance and the collection

"amounted to the magnificent sum of $13:50c". On the Sabbath

3rd September he preached in Third United Presbyterian

Church in Pittsburg after which he went West to Petersburg

in Illinois before returning to the East and visiting

Philadelphia, Baltimore, Princeton, Albany, Troy,

Kinderhook, Newburg, New York, Brooklyn, Jersey City and

many other places. He also went to Toronto and gives us an

account of seeing the Niagara Falls. His was one of

temporary disappointment and as he records, "The longer one

looked at them the more awful and awe-inspiring they

became". He was a man who enjoyed good preaching and in his

little book he tells of the various preachers he heard. Some

he heard gladly and others he described as being profane in

their handling of the text. He was a man with a great sense

of humour as is shown when he tells of falling asleep while

listening to one preacher. He says "I fell asleep actually

with my eyes open- a new plan which I would recommend to all

sleepers in church!" On his last Sunday in America, the 6th

November, 1870 he preached in 7th Avenue UP Church in New

York at 10.30 a.m. He went to church in the afternoon and

again in the evening and heard two other preachers, one whom

he described as good and the other as no preacher at all!

The

Remaining Years

Mr. Strain was a man who enjoyed preaching and he seemed

to have gifts in that direction. He was what may be called a

textual preacher and from records available together with

the comments of Mr. Jamison he must surely have been one of

the foremost preachers of his day. Now back in the work of

the ministry after his tour of the United States the task

that lay ahead of the people was the building of the manse.

During the 1870's Strain gave himself to the work of the

ministry. His powerful preaching and winsome character won

the hearts of many people. It was during this period that he

met Maria Lousia Greer, daughter of the Rev. Thomas Greer of

Annahilt and they were married by special licence during

1873. Their marriage was blessed with two sons and a

daughter. They were the first family to live in the new

manse in which Strain had been so instrumental in seeing its

construction and which is still the manse of First Dromore

to this present day. Dr. Strain was not immune from much of

the suffering that life in those days had to offer. Their

only daughter Lizzie, born on 3rd November, 1880 died just a

few months before her 16th birthday on 26th August, 1896.

Dr. Strain was never a robust man and had never enjoyed good

health and the death of his only daughter was a severe blow

to the family. Just a few years earlier, in 1881 he had been

granted special permission by the General Assembly to retire

on the grounds of ill health, something he declined to so.

In fact in the next few years he seemed to be even more

diligent and studious as he gained his Doctorate in 1885.

His two sons graduated, J. K C. Strain with a B.A. and T.

G. Strain who received his B.A. from Cambridge. With the

death of his daughter adding to his afflictions Dr. and Mrs.

Strain continued in the work at First Dromore. He continued

to preach and to catechise as health permitted. He saw his

work in the congregation and with his people otherwise a man

of his gifts and talents may have been widely used in the

various courts of the church. During 1884 the World

Presbyterian Alliance was held in Belfast and it is most

likely that Dr. Strain would have been present at such a

gathering considering that some of the finest theologians

and outstanding preachers of the day were in attendance.

However any mention of his membership of Committees or

Boards of the General Assembly are not recorded and would

confirm that his work was within his congregation. Dr.

Strain carried on and as a report in The Irish Presbyterian

of February 1908 states "he continued to work on and died in

harness." On the 28th December, 1907 Dr. Strain left this

scene of time having served all his ministry in First

Dromore. The account of his death was recorded in The

Witness of Friday 3rd January 1908 and read as follows "We

deeply regret to have to announce the death of the Rev. J. K

Strain LL.D., minister of First Presbyterian Church,

Dromore, which occurred on Saturday at the Manse". The

report of his obituary ran for almost two columns and gave

details of the funeral service.

The Final Farewell

New Year's day 1908 was a solemn and sad day for Dromore

and especially for the people of First Dromore. This was the

day that Dr .

Strain was buried. A service was held at the Manse and the

Rev. J. W. Gamble read from the Bible and the Rev. W. G.

Glasgow led in prayer. The funeral cortege was large and

impressive as it made its way from the Manse towards the

church. Children from the Sabbath School preceded the hearse

as the coffin was borne from the manse to the church by

relays of the Session and Committee. Following immediately

behind was a number of his fellow ministers including Rev.

Dr. Davidson, Moderator of the General Assembly, Prof. S. L.

Wilson, R. W. Hamilton, J. Rentoul, (Banbridge Road), J. W.

Gamble, T. Dunn, J. Mitchell and James Irwin, Moderator of

Dromore Presbytery. .

Strain was buried. A service was held at the Manse and the

Rev. J. W. Gamble read from the Bible and the Rev. W. G.

Glasgow led in prayer. The funeral cortege was large and

impressive as it made its way from the Manse towards the

church. Children from the Sabbath School preceded the hearse

as the coffin was borne from the manse to the church by

relays of the Session and Committee. Following immediately

behind was a number of his fellow ministers including Rev.

Dr. Davidson, Moderator of the General Assembly, Prof. S. L.

Wilson, R. W. Hamilton, J. Rentoul, (Banbridge Road), J. W.

Gamble, T. Dunn, J. Mitchell and James Irwin, Moderator of

Dromore Presbytery.

At the church the funeral service was conducted by the

Rev. R. W. Hamilton who spoke of Dr. Strain as a man "of

exceptional abilities, of strong and intelligent

convictions, of powerful and persuasive speech, of high

Christian character" and went on to say that he had been an

able minister of the New Testament that needed not be

ashamed. Dr. Strain was described as a preacher with fine

Evangelical fervour, devoted to the salvation and

edification of your souls.

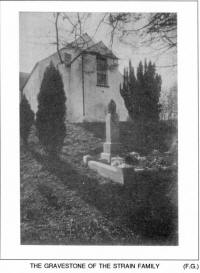

So after 48 years in Dromore the remains of James Kirker

Strain were laid to rest in the adjoining graveyard. His

widow left Dromore shortly afterwards and went to live in

Dublin with her sister. She attended Adelaide Road Church

until at the age of 76 she died unexpectedly on 24th

February, A fine tombstone was erected and still stands in

the graveyard today, at the rear of the church. An

inscription reads: "He was a faithful earnest and eloquent

preacher of the Gospel, a true friend to his flock, a man

greatly beloved."

Bibliography

The story of a Visit to America. J. K. Strain,

Belfast 1871.

The Church on the Hill. Donald Patton, Banbridge 1981.

County Down, A Guide and Directory, George Henry

Bassett, Dublin 1886. Republished by Friars Bush Press,

Belfast 1988.

The Oxford Illustrated History of Ireland, edited by R.

F. Foster, Oxford University Press 1989.

A History of Ulster. Jonathan Bardon, Blackstaff Press,

Belfast 1992.

The Second Evangelical Awakening. J. Edwin Orr, London

1955.

The Year of Grace. William Gibson, Belfast, 1860.

The Witness and The Irish Presbyterian (Presbyterian

Historical Society, Church House, Belfast.)

MY UNCLE

SAM

By Sam Johnston

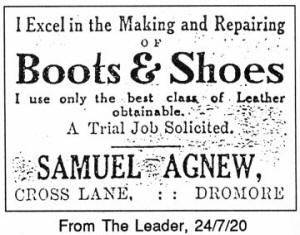

Sam

Agnew was born in the Kilntown district of Dromore in 1880

and died 1963. He was a many faceted, if unpolished rough

diamond. Just the type that would have appealed to Charles

Dickens who would most certainly have incorporated him, as

he did with Mr. Micawber and Barnaby Rudge, as a captivating

character in one of his novels had he ever encountered him. Sam

Agnew was born in the Kilntown district of Dromore in 1880

and died 1963. He was a many faceted, if unpolished rough

diamond. Just the type that would have appealed to Charles

Dickens who would most certainly have incorporated him, as

he did with Mr. Micawber and Barnaby Rudge, as a captivating

character in one of his novels had he ever encountered him.

He was a boot and shoemaker. He was a violinist. A

flautist (tin whistle and fife). A timpanist (Lambeg

drummer). A hunter (greyhounds, terriers and ferrets). A

witty raconteur. And being my mother's brother he was my

Uncle Sam; and thereby hangs this tale.

Sam plied his trade in a room off the kitchen in his

house in the Cross Lane. There he would sit on a low bench

with his implements on either side. The shoe, with a metal

last inserted, was held in place on his lap with a loop of

rope that went round it's instep and was tensioned by the

instep of his foot at the other end. It was the custom of

cobblers to use their laps in this way, and legs had to

withstand the pounding of hammers necessary in the mending

of footwear. This crouching posture was superseded - (in

Dromore at any rate) by John Andy Magill who pioneered the

method of standing at a workbench whereon the footwear was

mounted on lasts which could rotate in any direction. This

speeded up the task immensely and was much less laborious.

Allied to that was a machine with whirling buffs and brushes

which gave a "good as new" appearance to the repaired

footwear at the touch of a button.

Sam looked what he was - a character. A small stout butt

of a man with powerful arms and strong neck leading to a

mobile face that mirrored his many moods. Atop of all this was a thick crop

of hair that stood up as stiff as a yard-brush and was

underpinned by eyebrows of like density. A squat nose with a

convenient upturned tilt prevented his metal-rimmed

spectacles from falling over it's edge. The old adage warns

not to judge the book by the binding, and Sam's physiognomy

belied the prodigious memory housed behind it. As my mother

used to say, "Your uncle Sam has a head like an almanac". He

could recite every town in the 32 counties and his favourite

ploy was to ask schoolchildren to name them, which none of

them could. His next question would be, "Do they teach you

nothing in school these days?". Or he would ask them, "If

the third of six was three, what would the fourth of twenty

be?" I gained his respect when I answered that one

correctly!* Then there was his great conundrum which still

puzzles me to this day. It posed the question. "If a farmer

sowed a field of corn, he was sowing, and if his wife was

sewing a dress, she was sowing. If the farmer later said "We

have sewn to-day" would it be spelt `SEWN' or `SOWN'?

mirrored his many moods. Atop of all this was a thick crop

of hair that stood up as stiff as a yard-brush and was

underpinned by eyebrows of like density. A squat nose with a

convenient upturned tilt prevented his metal-rimmed

spectacles from falling over it's edge. The old adage warns

not to judge the book by the binding, and Sam's physiognomy

belied the prodigious memory housed behind it. As my mother

used to say, "Your uncle Sam has a head like an almanac". He

could recite every town in the 32 counties and his favourite

ploy was to ask schoolchildren to name them, which none of

them could. His next question would be, "Do they teach you

nothing in school these days?". Or he would ask them, "If

the third of six was three, what would the fourth of twenty

be?" I gained his respect when I answered that one

correctly!* Then there was his great conundrum which still

puzzles me to this day. It posed the question. "If a farmer

sowed a field of corn, he was sowing, and if his wife was

sewing a dress, she was sowing. If the farmer later said "We

have sewn to-day" would it be spelt `SEWN' or `SOWN'?

After some fifty years I'm still awaiting the answer.

Sam started his working life in Ligoneil with a

watchmaker and jeweller. He told of a man who brought in a

watch which wouldn't go and said he would call for it next

day. Sam watched carefully as the boss examined the works

through his eyepiece and gave them a sharp puff with his

mouth, whereupon the watch started working. "If I'm not here

when he comes back for the watch, charge him five shillings

for it!" he told Sam. The client returned and as the boss

was absent, Sam charged him ten shillings. "Why did you

charge him twice what I told you?" asked the boss on his

return. "Because", said Sam "I blew into it too!!"

But life in the big city did not appeal to young Sam and

yielding to nostalgia he walked the twenty miles home. He

was soon apprenticed to a shoemaker named Mr. Purdy, who was

a master craftsman by all accounts. Then, on having his time

served, he married his wife Rachel and started his own

business in Dromore.

Flexi-hours may be a modern method of conducting business

but Sam was working this system 70 years ago! Being his own

boss he could lie in bed as long as he liked before starting

to repair some footwear, but often when the sun penetrated

the workshop window the call of the open country would be

too much for him and he would down tools, put on his outdoor

clothing, open the door to the backyard to admit a

greyhound, a lurcher, an Irish terrier and a Jack Russell,

all barking and whining in anticipation of the impending

hunt for hares and rabbits. Then, putting a leash on the

greyhound, he would open the front door through which would

cascade this canine cavalcade which petrified passing

pedestrians as the hairy horde swarmed around them.

The Magherabeg district was his favourite hunting ground

and he found it convenient to get there by walking the

railway line from the Maypole bridge. He would tell of two

near mishaps which befell him on such journeys. Seeing a

train approaching he went a few yards down the very steep

embankment and held the greyhound until the train passed.

The dog panicked as the engine went by and leaped out of his

grasp, sending his roly-poly body tumbling over and over

down the steep slope. He feared for his limbs, if not his

life, but fortunately a clump of whins brought him to a

prickly halt half-way down.

The other episode he told, tongue-in-cheek, was when he

was walking the line with the rocky walls of the `cutting'

on either side. The strong wind blowing in his ears muffled

the sound of the overtaking train. It was only the vibration

of the sleepers that made him look around to find the engine

almost on top of him! So he took to his heels and ran in

front as hard as he could. The engine driver spotted him and

shouted, "Run up the bank man! Run up the bank!" Whereupon

Sam shouted over his shoulder, "Bank hell! It's taking me

busy beating you on the flat!"

The hunting over he would return to his workshop and work

until nearly midnight. It was an ideal existence which many

envied.

His workshop was seldom without company and at times

overflowed with people who congregated there to enjoy the

crack and music, for he loved to entertain with fiddle, fife

and tin whistle. In those pre-T.V. days Agnew's was the

place to go for guaranteed pleasure.

His

floor was strewn with footwear, newly repaired, awaiting

repair or beyond repair. Once when a farmer sought him to

fix a pair of boots, Sam looked them over in disgust and

gave his opinion. "If there had been uppers on them I might

have been able to put soles on them, or if there had been

soles on them I could have put uppers on them, but they're

clean done." The farmer asked despairingly, "Surely you can

do something for me?" "Well," said Sam, "I could sell you a

pair of laces, for the eyeholes aren't too bad!" His

floor was strewn with footwear, newly repaired, awaiting

repair or beyond repair. Once when a farmer sought him to

fix a pair of boots, Sam looked them over in disgust and

gave his opinion. "If there had been uppers on them I might

have been able to put soles on them, or if there had been

soles on them I could have put uppers on them, but they're

clean done." The farmer asked despairingly, "Surely you can

do something for me?" "Well," said Sam, "I could sell you a

pair of laces, for the eyeholes aren't too bad!"

A good selling line was second-hand Army boots which

arrived from time to time in hessian bags. They were not

always tied in pairs and the prospective buyer had to sort

through them to get a pair that matched.

They were priced at 15 shillings (75p.) and according to

Sam, he had little or no profit at the price. So much so,

that when a client asked him to wrap his purchase in paper,

Sam refused, saying if he wrapped them he would be giving

away his profit.

The snag about the Army boots was that they were studded

with broad headed nails called protectors and if one fell

out with usage it left a small hole in the sole through

which water would seep on rainy days.

A purchaser was leaving the workshop with a pair under his

arm and with an afterthought turned and asked Sam, "Will

these boots keep out the wet?" "What age of a man are you?"

asked Sam. "I'm 64 come June," he said. "Well surely to

goodness a man come to your time of day knows to keep out of

puddles," said Sam.

One of the eternal snags in commerce is getting prompt

payment for services rendered. Sam had been bitten too often

in that respect, so he had several notices hanging in

eye-catching positions. Here are some of them.

`My work is good. My price is

low.

Cash on the nail before you go!' |

or |

`Good friends did come and I

did trust them

I lost their money and their custom.

To lose them both did grieve me sore,

So I've decided to trust no more.

PROMPT PAYMENT PLEASE!'. |

| And hanging on an ancient clock

that hadn't worked for years was the short,

blunt reminder: `NO TICK HERE'. |

With so many demands on his time and passtimes customers

would sometimes find that their shoes that should have been

ready and mended, still hadn't been touched. He would

promise sincerely that they would be ready early next week.

"Sure you told me last week," ranted a disappointed lady,

"And you'll never get to heaven for telling such lies".

"Them's not lies, M'em", explained Sam, "Them's what you

call `business fibs"'. Implying that one could tell

`business fibs' with impunity while other untruths condemned

the teller to hell's fire!

One of the reasons for the late delivery of day-to-day

repairs was when Sam undertook to manufacture handmade

footwear. This was a time-consuming job and entailed the

addition of little leather patches on the wooden last or

pattern to allow for the client's bunions etc., and only

those people with above average wages could afford to pay

for the handmade article. If they squeaked when walking this

was regarded as a status symbol, denoting one could afford

such up-market footwear. My wife tells me that around Comber

way people translated the `squeak squeak' as saying `not

paid, not paid'. Sam confided in me that to guarantee the

squeak he would insert a piece of felt between the leather

in the sole and that gave the required sound as the leathers

flexed when walking.

Uncle Sam, being self-taught, played all his instruments

by ear and his stance when he played the fiddle was unique

for instead of resting it under his chin, he held it low on

his left breast, and his head was turned away at

right-angles instead of in line with the strings. His face

was set in an impassive mask as he gazed fixedly at the

wall. Then with the tune finished he would explode in a

hearty laugh and ask, "What do you think of that one, bhoy?"

And what titles he had for them! Such as `Erin's Farewell',

`The Liverpool Hornpipe', `The Irish Washerwoman', `The

Cuckoo's Nest', `The Blackbird', `The oul-rag-a-doo', "The

Mason's Apron', `The Wind That Shakes the Barley', Pop Goes

The Weasel', `The Oul Sows Ramble To The Pratie Bing', `A

Cup of Coffee' ("There's no sugar in it!" he always

remarked) `The White Cockade', and so on and so on. The

titles are still etched in my mind though I have forgotten

some of the tunes.

He would tell the true story, punctuated by much

chuckling, of hearing about a man called Pat who was

learning to play the fiddle by scraping and scratching at a

tune called "Sausages for Tea", which was putting his

brothers round the bend, and his own life in danger. One day

Pat's brother Joe dropped in to see Sam and after a bit of

chat, Sam reached for his fiddle and said, "I'm going to

play you a great tune called `Sausages for Tea'." "You'll do

damn all of the sort!," snorted Joe, making for the door.

"I've had `Sausages for Tea' for the last fortnight and I

can't take any more," and disappeared like a flash. By the

time Sam dandered to his front door Joe was disappearing

round the Gospel Hall corner some sixty yards away, with his

coat tails flying!

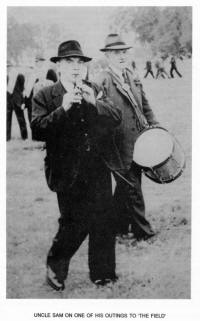

Sam's other instruments were the tin whistle, the fife

and the drum. Orange parades would find him fifing to Lambeg

drums and how he detested aimless blattering by beginners.

"That rumbly-dumbly sort of playing is just a waste of my

music", he would say, sticking the fife in his hip pocket

where it remained till more competent drummers took over. He

had a miniature drum about half scale in his workshop and I

used to whistle a tune and He would drum to it, - and what

drumming! The staccato reverberation and changing tempos and

rhythms in that small room, produced a tingling in the spine

and a stinging in the eye that was exceedingly exhilarating

and perhaps primitive. It had nothing to so with political

connotations or religious undertones, for Sam was not a

bigot, as the multiplicity of his customers testified. It

was an extrovert expression of the rhythms housed in that

barrel of a body. Invariably he would remark after such a `rivetting'

session. "That will help to soften the wax in your ears".

There were other music-makers in the house in the form of

canaries and `mules' and when silent Sam would encourage

them to sing by calling, "Bully Dick, Bully Dick!" and

invariably they would respond with their sweet trilling. The

mules were dark feathered birds and were the offspring of a

canary mated with a goldfinch, which resulted in above

average singing ability, but, being hybrids, they, like the

four-footed mules they were named after, were unable to

reproduce their species.

As a teenager I would frequent Uncle Sam's about three

times a week and would lend a hand by stripping off worn

soles and heels ready for repair. To the repaired footwear I

would apply an inky wash to the soles and heels. The sides

of the heels and uppers were daubed with a pitch-like

substance called `heelball' and gave the footwear a pleasing

aspect. I mention the foregoing so that the reader will

better appreciate another of Sam's favourite stories. He was

coming home one evening and noticed a publican standing in

the doorway of his premises trying to hold upright a noted

tippler who, with a skinful of drink and dearth of cash in

his pocket, had become a nuisance to other customers. Sam

was hailed and entreated by the publican to take the drunk

home, to which he replied, "When I get my job done and

nicely heelballed, I put it in the window for the public to

see my handiwork, so I suggest your man should be put in

your window and let the public see what you can do!"

Before myxomatosis ravaged the rabbit population they

were the poor man's chicken, and indeed, when properly

cooked, were every bit as nutritious and tasty. They were

trapped in great numbers by being driven into nets placed at

the ends of their burrows down which they were pursued by

ferrets. Sam bred ferrets for this purpose but so great was

the demand for them, he had to buy them in from outside

sources. Most of these were delivered by rail and were

ravenous when they arrived. One such consignment was

released from their container and commenced to quest all

around the room in search of food. After several re-counts

it was agreed that one was missing from the original order.

With an after thought, Sam upended the box and out tumbled a

handful of straw and the pelt of the missing ferret! It had

been cannibalized by it's ferocious `friends'. When I

expressed regret at his loss of profit, Sam consoled me by

saying he would spread the cost of the dead one over the

price of the others. "Sure", he said, "They're getting a

ferret and a bit anyway!"

He had fished every river, Lough, lake and dam for miles

around, and I would listen enthralled as he told of big fish

he had caught and the even bigger ones that got away. I had

been taken by my father to fish at a Lough at Shanrod for

perch - I still have vivid memories of knocking back the

buns and lemonade that Da bought in a wee shop nearby. Sam

enquired how we had got on at the fishing and I told him we

had caught a dozen medium sized fish, but the big one, as

always, got away. We actually had it in the net but it gave

one almighty leap, broke the line and escaped; which was a

pity for it weighed two pounds exactly! He was briskly

hammering in nails as he listened and as the tempo of

hammering eased I could see he was turning over in his mind

what I had just told him. Finally he stopped, looked over

the rim of his glasses, pointed the hammer at me and said

accusingly, "Houl on a minute, lad. How did you know it

weighed two pounds if it got away?" "Because," said I, "It

had the scales on it's back!" "Oh! Go to hell!" he exploded

and vented his anger with a venomous attack on the nails. He

had `walked into it' and I felt sorry for leading him on,

for a great maxim of his was, "Chaff will not catch an old

bird, it takes corn." But he soon forgave me and caught out

lots of others as he retold the tale again and again.

I mentioned his dogs earlier. The only one he would let

out on it's own was the big lurcher - a cross between a

greyhound and a large collie-and as I was crossing the

Square on my way to Sam's, I noticed this dog scavenging in

entries and shop doorways. I told Sam what I had seen and he

gave a great laugh and said, "He's a quare dog thon! He

lifted a pound of sausages out of a woman's basket in the

butchers last week, and I'm waiting on him coming home now

to see what he's bringing me for the dinner!"

He took to wearing the inner tube of a bicycle tyre and I

asked the reason. "Well." he explained," I can't be bothered

adjusting my belt after I've had a big feed, but the tube is

handier for it comes and goes with the tide".

The coalman called one day and accused him of not

speaking to him when he passed in the street last Saturday

night. "Sure I didn't know you," said Sam, "You must have

had your face washed!"

There was the occasion when, as a lad, he was walking

along the road eating a piece of bread. He met a woman with

a small dog which kept jumping annoyingly around him, trying

to get the bread. "Shall I throw it a piece?" asked Sam.

"Please do," she replied. Whereupon Sam caught the dog and

threw it over the hedge!

He liked a game of football and often told of when they

were boys, his brother and he were on the same side, playing

with a hanky ball' in the roadway. As Sam dribbled through

he was fouled with a painful kick to the shin. He went down,

crying with the pain and eventually his brother came over

and said, "Stop your blirting! Sure we're getting a

penalty!"

I could go on but I'll end with the story of the night

his wife burnt the porridge! My father and I were having a

great chat with Sam in the workshop and Rachel, Sam's wife,

who had been making a pot of porridge for supper, joined us.

Suddenly Sam's nostrils twitched and he let out a gulder,

"You've burnt the porridge, woman!" Up we all got and made

for the kitchen. Sam, in a towering rage, shouting abuse at

Rachel, who panicked and grabbed a wooden spoon and would

have stirred the porridge but my father stayed her hand.

And, trying to pour oil on troubled waters, admitted to

occasionally burning his, but if one spooned off the top

layers carefully they tasted not too bad. But Sam was

furious and yelled "If they taste as good as you say we'll

burn them every bloody night from this on!" My whole body

vibrated with suppressed laughter at the thought of Rachel

presenting a burnt offering ad infinitum. Though I expected

Sam to hit me a clout in his anger, I had to explode with

one great bellylaugh which triggered off a chain-reaction

which left the four of us hilariously helpless. Thus the

situation was defused in humour.

When Sam died, old Aunt Rachel was taken to live in her

son's home where she spent the rest of her days in a

serenity and style she had never known before. Whenever I

visited her she was always sure to place her hand in mine

and shaking gently with laughter she would say, "Sam, will

you ever forget the night I burnt the porridge?"

As I grew older I met the girl who became my wife and our

`coortin' left me with less time to see Uncle Sam. He

noticed my absence and asked me had I got a girl? I told him

all and jokingly said I hoped my infrequent visits wouldn't

result in him removing me from his will.

"No. I haven't struck you off, but now you'll only get a

'mention'," he said.

However, he did leave me a legacy. A legacy of homespun

anecdotes and yarns, memories of quaint figures of speech

and his inimitable ability to cheer up the cheerless.

FOOTNOTE:

Looking down the years I can remember cobblers in every

street in Dromore. There were the Cammock's, Billy and

Johnny, Harry and Johnny Morgan in Meeting Street. Rampart

Street had a Mr. Clokey. Bridge Street had the Wilkinsons

and there were various men who worked for Castles Bros., one

of whom was Charlie McKee. John Andy Magill wrought round

the Rocks along with his son Billy and Bobby Carr. Jemmy

Walker and Son operated in Church Street. Gallows Street had

Stanley Jess, Tommy Rice and James McComish. Uncle Sam Agnew

plied his trade in Cross Lane. Geo. McCalister had, besides

himself, his son Charlie along with Willie Cherry, Thomas

Beggs and Herbie McClune and Mount Street had Billy Barr and

Robert McDonald. There was plenty of work for them all until

synthetic soles ousted leather in footwear, making shoes

much cheaper.

Indeed it was more economical to buy new ones than to

have the worn ones repaired. So cobblers became a dying

species, with Wilfred Mason being the last craftsman to

close his door in 1992.

* Answer to question = 71/2

ST. COLMAN'S PRIMARY

SCHOOL DOWN ALL THE DAYS

|