|

BY COACH AND CAR TO NEAR

AND FAR!

A VICTORIAN TIMETABLE

by Rosemary McMillan

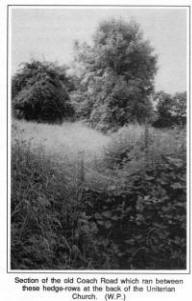

The

Ulsterbus Belfast to Dublin Express coach glides powerfully

away up Church Street. The passengers are cocooned in air

conditioned comfort and soothed by taped music. It all makes

a sharp contrast with the possible scenario in the Square

one hundred and thirty seven years ago. Then the horse drawn

Royal Mail Coach would have rattled and clattered down

Bridge Street and into the Square, pulling up to a noisy

halt outside the Post Office. Any alighting passengers would

have been both bone-shaken and travel-stained. The

Ulsterbus Belfast to Dublin Express coach glides powerfully

away up Church Street. The passengers are cocooned in air

conditioned comfort and soothed by taped music. It all makes

a sharp contrast with the possible scenario in the Square

one hundred and thirty seven years ago. Then the horse drawn

Royal Mail Coach would have rattled and clattered down

Bridge Street and into the Square, pulling up to a noisy

halt outside the Post Office. Any alighting passengers would

have been both bone-shaken and travel-stained.

Apart from these differences in comfort, the cost and the

time taken for the journey are also dissimilar. In the 19th

century the journey from Belfast to Dublin cost �3.5s.0d.

for two insider seats and took 13 hours to accomplish. Today

that journey can be done in 3 hours and costs �9.50 per

person, day return.

Slaters Commercial Directory of Ireland 1856 gives an

insight into coach and car travel from the town. The number

of people providing the service reveals competition for

passengers but there is no clue as to whether the "cars"

were Jaunting cars, side cars, brakes or worse!

Some of the departure times are also quite amazing. Can

you envisage a Royal Mail car leaving for Ballynahinch,

Comber, etc., every morning at twenty five past two? or

Belfast at ten minutes past four?

Amended extracts from Slaters "Commercial Directory of

Ireland" 1856

To Dublin The Royal Mail left from the

Post Office every morning at eight and a Coach every

night at eleven.

To Ballynahinch, Comber. etc.; The Royal

Mail car left from the Post Office every morning at

twenty-five minutes past two.

To Banbridge Cars from Edward McCartney's

(who was a butter factor as well as running the posting

establishment) Andrew Jelly's (a spirit and porter

dealer) and John Scott's (a surgeon in Bridge Street)

every morning at nine.

To Belfast The Royal Mail car, from the

Post Office every morning at ten minutes before four and

every night at a quarter to eleven.

To Lisburn A car from Edward McCartney's

every morning at a quarter past seven, arriving in time

for the Ulster Line of Railway train at a quarter before

nine and again occasionally leaving Dromore at nine; a

car from Andrew Jelly's every Tuesday and Friday morning

at a quarter past nine and one from John McGrady's at

the same hour; all go through Hillsborough.

To Lurgan Cars from Edward McCartney's, Andrew

Jelly's and John Scott's every Thursday morning at nine.

The running of some of these local cars to Lisburn and

Lurgan corresponds to the Market Days, Tuesday and Thursday,

in these towns.

By 1863, the coach/car service from Dromore had been

considerably reduced. This is probably indicative of the

number of people who now chose to travel on the Banbridge,

Lisburn and Belfast Co. railway line which had opened on the

13th July in that year.

The change is also reflected in this excerpt from the

Belfast and Ulster Directory for that year which advises us

of the following:

Conveyances

To Lisburn - Every morning, (Sunday excepted) from

Dawson's (Dawson was a car owner and spirit dealer) and

McCartney's in time for the first train and for the forty

five minutes past ten train to Belfast.

Curiously there appears to have been no road transport

between Dromore and Moira, the nearest rail station on the

Ulster line, even though a fairly good road between them was

mapped by Daniel Anderson as early as 1755.

ALEXANDER COLVILL

WELSH

by Gilbert Watson

Alexander Colvill Welsh had an established business as

a glazier and painter in Dromore, Co. Down in the

nineteenth century but he enjoyed a much wider reputation

for his collection of antiquities. He was the son of

William Welsh of Dromore who married Jane Dickson the

daughter of Joseph Dickson and Jane Colvill, and the

great-grandson of Dr. Alexander Colvill. His paternal

grandfather was George Welsh who was born in Moira in 1720

and is buried in the Cathedral grave yard at Dromore along

with his two wives.

Alexander Welsh was also married twice. Firstly to Mary

Trail by whom he had three children; Anne

Blackwell, William and Jane.

Mary died in 1838 and he

married secondly Anne Frazer by whom he had four

daughters, Anne born 1844 who married John Ellis; Alice

Margaret born 1848; Elizabeth Harberton who married a Mr.

Finlay; and Alice Jane born 1855 who married Richard

Watson of the Maze.

Welsh was a well known and respected collector and

antiquary and was very knowledgeable on the history of

Dromore and it is unfortunate that little of the vast

store of knowledge which he possessed is on record. He was

in correspondence with another noted collector Dean Dawson

of St. Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin, during the 1830's and

together with John Roggan of Ladies' Bridge was

instrumental in providing further material from the North

of Ireland for the Dean's collection.

Welsh viewed the Dean's collection during a visit to

Dublin in 1839 and he was so impressed by what he saw that

he admits in a letter that his own collection was lowered

in his estimation. The Dromore collection of artefacts was

viewed in the mid 1800's by John Roggan, who was so

impressed with the great variety and number of articles

that he composed and published "A Quaint Catalogue of

Antiquities in the collection of Mr. Welsh, Dromore,"

which is written in rhyming couplets. The full catalogue

is given below and indicates what a valuable museum of

treasures was once housed in Market Square

Huge folios and

quartos, heaped pile upon pile,

Then beautiful paintings in every style;

With maps of all countries and charts of all

seas,

He sees the whole globe while he sits at his

ease,

Can trace all its mountains, each river and

lake:

Describe every people, their colour and make-

With beast, bird, and insect, fish, reptile, and

all

That have an existence on this earthly ball.

His fossils are numerous, many, and rare

Even teeth of the lion, rhinoceros, and bear,

The head of an otter, and one of a fox,

Petrified hard as the primitive rocks;

Fragments, once oak, now certainly stone,

Petrified holly used oft as a hone;

Petrified ash and petrified yew,

Petrified thorn, and sycamore too;

Petrified urchins and petrified snakes,

Petrified fish, from both rivers and lakes:

Oysters and razor fish, too, petrified,

And limpets and muscles, and cockles beside;

Univalve, bivalve, and multivalve shells,

Curious stalactites, from grottos and cells;Dendritics, zoophytes, and belemnites too,

Corals and corallines, white green and blue,

Surphurs and salts, native metals and ores,

Curious pentacrinites, fine madrepores,

With some of the gems of Lough Neagh's sandy shores.

A pebble, the finest from Lough Lean,

And a neat little emerald of beautiful green;

Schists, fluors, and quartz, a handsome actite.

Silex, amygdaloid, ochre, and granite;

Gypsum, and pieces of Derbyshire spar,

And marble of various kinds from afar.

His boxes of earths all differ in hue,

From argill's dark red to fuller's pale blue;

'Tis pleasing indeed to hear him explain

The kinds best adapted for each kind of grain.

Ninety-eight amulets and thirty-two beads,

Many of which were used as decades

In form, orbicular, octagonal, square,

Of crystal, of amber, even pearl so rare.

Pieces of crosiers, a rare crucifix,

An old broken mitre, a chalice and pix;

A font was dug up near the Abbey of Saul,

And an old heathen idol, the rarest of all;

The pan of censer, of bronze finely polished,

Found near a church fierce Cromwell demolished;

|

And a square iron bell, so

injured by time,

No effort will cause it to yield the least

chime;

The parts are united with rivet and solder,

Than the famous Clogroe it's undoubtedly older.

Of rich polish'd brass, a rare antique

vessel,

I'm led to conclude it the bowl termed

"wassail,"

Brought here by some Anglo-Saxon invader,

Or left on our shore by an adventurous trader.

Two beautiful methers, a carousal cup,

From which the fell Ostman his boir would sup,

From heather fermented - so potent the juice,

Great draughts would inebriate and madness

produce;

The blood thirsty Pagan, with gore-covered

steel,

Would then make the natives his tyranny feel;

Nor ceased hath tradition the hardships to tell,

In those cruel times our forefathers befel.

Say, muse, were the bridle, bits, stirrups, and

spurs,

Used in King William's or Oliver's wars,

They may have belonged to some knight of old

Bessie,

Or seen the famed fields of the far famed Cressy.

He has pieces of greaves, shirts of mail and

vambrace,

A vizier and some other guards of the face,

Old gorgets and helmets, the half of a shield,

And a part of a sword from Canne's dread field;

Bills, battle-axes, old spears, and old skeans,

And dirks that were used on Colloden's Plains;

A gauntlet and glove near eaten by rust,

Were used in the days of Richard the First.

Of brass he has seventeen beautiful celts,

With sockets and ears, which hung from the belts

Of others quite plain exactly a score,

And hatchets of stone a hundred and more;

Of flint he has arrow heads, lances and spears,

The tedious collection of many long years.

A terrible axe was in sacrifice used,

When the Flamin the reason of mankind abused-

Six inches broad, half a cubit in length,

Of stone finely polished and form'd for

strength;

A statue of stone was found near the Nile,

An Egyptian god executed in style;

Beautiful Lachrymatories, well formed urns,

Adorned with lines of most curious turns;

An hundred old pipe to the Danes some ascribe,

Others doubt that they ever belonged to that

tribe.

|

He has various stone mills, one a beautiful quern,

Long, long, were they used by the sons of old Erin.

Two internal mummies of well baked clay,

And a Borneo idol to him found its way.

He has beautiful bracelets, brooches; and rings,

Which were worn of old by our Queens and our Kings;

A rare antique pin of Corinthian brass.

The head ornamented with fine ancient glass:

Such fastened the mantles of heroes of old,

And some were of silver and many were gold;

A large oval button of high polished jet,

Surmounted the pin where the Mantle folds met;

Two curious loops of the precious ore,

To fasten the doubtlet that Monarchs oft wore.

Of old Irish slippers he has got a pair,

Without sole or heel, to meet with how rare;

With thong most ingeniously stitched in front,

But one has some curious carving upon it.

Of matwork a singular fragment hath lain

In earth, I presume, since time of the Dane,

Most curiously wrought by some masterly hand,

Its original use how few understand:

'Tis compact in the texture as cloth nearly fine,

The fabric is wood, undoubtedly pine;

A part of a skull in an urn was found,

An inch near in thickness, and perfectly sound,

That centuries ten must have lain in the ground;

He has medals, medallions, and coins new and old,

of silver, of copper, of brass, and of gold;

Of gold he has seventeen coins mostly rare,

Three hundred of silver, some round and some square;

Of copper five hundred, one hundred of brass,

When James abdicated he caused here to pass;

The coins of the Popes our notice first claim,

I'm told that precedence is due to the name,

I think he has some of the fourth Adrian,

With others quite down to the last reigning King;

The Emperors next of course come in view-

of these he has German and Russian too,

And handsome Napoleons also a few;

A handsome medallion of Charlemagne,

With coins struck for Prussia, Poland and Spain,

A few struck for Sweden, by Charles and hot,

And some by that traitor to France, Bernadotte;

A number of those by the fell Bourbon Line,

With Burgundy, Tuscan, and Austrian fine;

Dalmatian, too, must be added to these,

And some of the Sultan's and some Portuguese;

Of Venice, Genoa, the Sicilies some,

And from Switzerland, Holland and Belgium they've come;

|

Of Charles the Rash, a beautiful coin,

Of William's a few, who fought at the Boyne;

Of all of the George's, of Mary and Anne,

Henry the Third, Seventh, Eight, and King John;

Two of the Edward's One, five the Confessor,

The Charles's Bess, and James the transgressor;

A beautiful sample of Scottish produce-

Alexander, the James's and David, and Bruce;

The coins of Old Erin appear, but, alas!

Of these he has few, save of copper or brass,

along with her rights her Antiquities fled,

Save such as she sunk round the graves of her dead:

what escaped the hand of the Ostman, so rude,

Was spoiled or destroyed by the bold Saxon brood;

Poor Man, too, exhibits here three brawny legs,

To be classed among Nations most anxiously begs;

When the coins of all Nations he marshals in ranks;

There's nothing but copper appears for the Manx's;

Thou Yankee, brave people, who would dare to be free,

He has paper and silver abundance of thee;

The arrows, the eagle, holds firm in its claws,

That Europe's proud despots triumphantly awes;

Thy coins, too, brave Hayti, tho' sable, thy race.

In his cabinet holds a conspicuous place;

Demerara, the Brazils, Barbadoes of thee,

He has many coins, and a handsome rupee;

Batavia, Java, and fertile Ceylon,

Thy coins make the shelves of his cabinet groan;

Thou far distant China, the nations how few

Can boast an antiquity equal to you

He has thirty-six of thy coins and thy medals,

Some bearing thy Emperors, other thy idols;

Tho' science its influence round thee hath shed,

Thy millions with Priestcraft are basely misled;

They worship in ignorance, tamely forego

Their reason, and bow to the poor idol Fo;

Besides the above he has many defaced,

By whom they were struck, nor their dates can be traced;

But still like the miser he adds to his store,

Though blest with abundance he still craves for more;

He digs up the Tumuli, raises the cairn,

To find something rare, and more knowledge to learn;

To search round the Cromlech, he long journeys takes,

Pursues the meanderings of rivers and lakes;

If fortune some antique will cast in his way,

His toil and his trouble it will more than repay;

|

The caves deepest corners he bravely explores,

In quest of some curious' crystals or ores;

Among Druid's circles, old mouldering towers,

He spends with delight some laborious hours;

Or seek old entrenchments, the place of the slain,

Perchance to find something of Saxon or Dane;

The abbey's wild ruins incrusted with moss,

The castle's rude walls, and the rath's ample foss

He constantly visits with diligent pry

In places like these, antiquities lie;

So, indeed, very little escapes his keen eye. |

Now cease gently muse for a moment or more,

Till I take a last look at this precious store;

I view this museum as historic pages,

Of artists, of heroes, of monarchs, and sages;

Even too of old nature, whose curious hand

Hath scattered such rarities over the land;

Were medals but struck for the worthy of fame,

No doubt Mr. Welsh to that honour might claim;

But monuments crumble, and medals will rust,

So his fame, worthy Sirs, to the muse we will trust. |

July 11th, 1840.

Welsh's collection and interest was never static and

his travels included visits to Dublin and Edinburgh. He

was continually adding to the quality and variety of

articles and a new pursuit in 1839 of collecting

"different sorts of newspapers" was built up to 271 in a

short time. His tenacity in the pursuit of artefacts is

illustrated by his admission that it took over ten years

to procure a square iron bell found in a Forth outside

Dromore and his eventual success, in acquiring it from the

lady owner, was the result of barter involving a silver

crucifix which "she thought more useful." On another

occasion, his business acumen is demonstrated in his

attempt to acquire an inscribed bell (the Clog Ban) from a

catholic family by enlisting the support of his

father-in-law who was "much thought of by the Roman

Catholic party owing to his political principles" and was

also intimate with the Priest who lived next door to the

vendor.

At the British Association for the Advancement of

Science Exhibition at the Museum, Belfast in 1852 Welsh

displayed various exhibits and the following have Dromore

connections.

(a) Portions of an ancient conical Cap of closely

woven rushes, found with a stone Axe, in Drumbroneth

bog, near Dromore.

(b) Three tri-handled cups, of black glazed pottery,

found in the original burying-ground of Dromore.

(c) Illustrative American Indian Arrow-head of flint,

with which the late Dr. Gillmer, of Dromore was wounded

in the leg.

Part of Welsh's collection of antiquities was acquired

by the Royal Irish Academy in March 1876 and was

subsequently transferred to the National Museum of Ireland

in the late nineteenth century. It consisted of some

several hundred archaeological objects ranging from flint

tools to bronze pins and brooches of the early Christian

period and prehistoric period pottery vessels.

The following description of the gold ornaments in the

Welsh collection is given in George H. Bassett's 1886 Co.

Down guide and directory and the sites in the vicinity of

Dromore where the specimens were found are recorded.

"In the Royal Irish Academy (Dublin) collection of

Irish Gold Ornaments, are some from the County Down. They

belonged to the late Mr. A. C. Welsh of Dromore. The

first, a spoonshaped object, one and eleven sixteenths of

an inch in width, and two and three-quarter inches long.

It is slightly concave, and has a slender tang with triple

row of small punched dots, near the edge. It weights two

pennyweights and sixteen grains. The second was a bowed

object and disc terminations and copper core; one disc

gone. It was found at Edenordinary. The third is a

specimen of ring money, a quarter of an inch thick and

threequarters of an inch in diameter six pennyweights and

three grains. The fourth is an unclosed hoop-shaped ring,

with copper core having double longitudinal flutings. The

core is visible to the extent of a quarter of an inch at

the centre of the circumference. It is five-eights of an

inch in diameter, a quarter of an inch in width,

two-tenths of an inch in thickness, and weights two

pennyweights and ten grains. It was found at

Ballymacormack.

Welsh was aware of the value of his collection as his

will dated 2 February, 1876 stated his intention "to make

provision for my wife and her children by my second

marriage by the sale of my antiquities and curiosities and

therefore they are not named in this my will as Legatus."

The beneficiaries were his own son William, his daughter

Jane and his nephew William Price. The will gives an

indication of the property he possessed, namely a tenement

in Market Square occupied by Hugh Herron, a tenement

garden in Gallows Street, a house in Mount Street occupied

by Betty Jane Kennedy, a tenement in Gallows Street

consisting of two houses and gardens occupied by David

Thompson and John Prentice as well as his residence in

Market Square.

Welsh's knowledge of Dromore has already been referred

to, and one of the few known articles by him is a letter

dated April 24, 1843 published in The Nation newspaper on

the subject of The Break of Dromore. The same account of

The Break is given in a footnote to the Montgomery

Manuscripts by the editor the Rev. George Hill who refers

to the account coming from an unsigned letter dated 24th

April, 1843 found among the papers of the noted historian

Mr. Samuel McSkimin of Carrickfergus. The account is that

of Alexander C. Welsh and his letter to the Nation was

probably at the request of the editor John Mitchell, the

Young Irelander. Welsh would have known Mitchell as his

cousin Robert Dickson was married to Mitchell's sister.

The introduction to the newspaper article is probably by

John Mitchell.

"The following curious and valuable information we have

just received from a Conservative friend, who, in adverse

circumstances, has acquired a knowledge of history, art,

and numismatics, a collection of antiquities that might

excite the envy of many a man with a great name:

April 24, 1843

Sir-You must think me a great procrastinator, or very

ungrateful, when I did not answer you kind favor sooner.

The truth is, after having made every inquiry from all the

oldest inhabitants of this place, I declined writing

relative to the "Break of Dromore" until a person who was

from home would return, he being one I depended more on

for information, as one of his ancestors was likely to

have suffered death on a charge of embezzling some of King

James' stores, so that many of the occurrences of 1690

were handed down by the family.

From all the information I can collect, I am come to

the conclusion that the flight at Dromore took place in

the townland of Ballymacormack, immediately adjoining the

town. The new line of road that passes through Dromore,

from Dublin to Belfast, bisects the battle field. It

occupied but a small space on the south side of the

Gallows-hill though not on a level, but a kind of glacis,

terminating at a bog-a place not ill chosen for a

skirmish, such as we may suppose it to have been, for

neither could have had much the advantage as to position.

General Hamilton's men were protected on their right by

the common-bog, and a small party in the narrow (Gallows)

street would have been sufficient to keep them from being

flanked on their left. The Protestant party had the bog on

their left; but their right lay open for attack. About two

hundred yards to their rere la Crows-wood, into which they

retreated when repulsed, and from thence they dispersed,

part of them passing the eastern extremity of the bog, and

made their way over Cannon-Hill, on the opposite side of

which lay the leading road to Killileagh and Donaghadee,

from whence some embarked for Scotland. What road the

remainder took I could not ascertain.

But the whole action must have occupied a very short

space of time; for according to tradition, a woman went

out to see the flight when it commenced, left bread to

bake at the fire, returned after the affray had

terminated, and during her absence the bread was not

burned. I conjecture none of the inhabitants of the town

were in the action; or if any, I will presume to state

that none of them fell. My reason for stating so is, had

any of then been killed in such a politico-religious

occurrence, their graves to this day would be pointed out,

and many is the tale of their great prowess would be

related, as the present churchyard was then the only

burying-place in the parish. And what strengthens me in my

opinion is, that a mile from Dromore, in a field on the

right hand side of the old turnpike road leading to

Hillsborough, a grave is there pointed out, green to this

day, said to be that of Marian De Ell, or De Yel, who, for

refusing some of James's soldiers a drink of buttermilk,

before she had taken off the butter, was drowned by them

in the churn, with her head downwards. And about

half-a-mile farther on, in a field on the opposite side of

the road, is another grave, said to contain the remains of

one Campbell, a powerful man, who, armed with only an old

sword, opposed part of James's army; but was soon

overpowered by numbers, thrown over the ditch, and buried.

(Query - When James's army passed, why did the friends of

the deceased suffer them to remain there, but have them

interred in consecrated ground?).

However, in this instance, I differ from tradition. I

rather think the graves alluded to are those of the two

soldiers of William's army, who, according to the Rev. G.

Story, "were shot near Hillsborough for deserting." Story,

or his informant, might have been in the rere of the army

at Hillsborough when the account reached him, and caused

the mistake, placing the transaction nearer that place

than Dromore, nor do I think the mistake improbable as the

two places lay only four miles distant, and Hillsborough

being a garrisoned town.

I have felt a pleasure in being called on to collect

the account of the "break;" for these notices, trifling as

they may appear were collected from the only remaining few

of the old inhabitants who are fast hurrying from the

scenes of this life to mix with the kindred dust of their

ancestors, who, in their turn, witnessed the scenes I have

written of.

In order to make you more acquainted with the

localities, I give the following notes:

Gallows-hill and Gallows-street

(formerly the leading road to Hillsborough through

Dromore). I conjecture they are corruptions of Galgas-hill

and Galgas-street, as the name of the town was

originally Ballynagalga.

Crows-wood was a few acres of land

then in a state of nature, covered with trees and

brushwood, commencing at the Eastern extremity of the

common bog, and extended up the hill on which the battle

was fought. It still goes by the name of Crows-wood,

although it is divested of all the timber, and in a

state of cultivation.

Cannon-hill situated on the

opposite side of the narrow valley from Crows-wood (and

in form of an inverted bowl), rises to an elevation

higher than some of the surrounding hills, from the top

of which is a fine commanding view of the town, and

about a half mile distant.

Cannon, or even musketry, from

this hill could have annoyed the enemy when in action;

probably those who fled to Killileagh might have

previously come from that part, and as this was their

direct road, it is likely part of them had been posted

here with cannon, if such they had; not is it unlikely

that it was a concerted plan with the proprietor, Mr.

William Holtrige, of Dromore, merchant, then a leading

character, and one of those mentioned in James's act of

attainder. The name of this hill partly proves the

circumstance, though I remember, when in infancy, to

have heard that the name was given it in consequence of

Cromwell's men placing cannon on it, and from whence

they destroyed the old castle and town; but we have not

the slightest historic foundation for the occurrence.

I would give credence to the account of those who fled

seeking refuge in Scotland; for an old lady, who has seen

some summer suns over ninety, who enjoys all her mental

faculties, recited to me the two following lines of a

popular song in her infant days, relating to the war of

1690.

`The run at Loughbrickland, the break of

Dromore,

Made Sandy and Willy take both to the shore.'

The last word in memoriam to Alexander Colvill Welsh,

who died in 1877 and is probably interred in the Cathedral

graveyard, we leave to J. W. Montgomery of Downpatrick who

in his poem Dromore in Rhymes Ulidian refers to the great

collector.

DROMORE

Tread softly, stranger,

o'er the ground,

And true obeisance pay;

For here lie buried men renowned

And brilliant in their day,

The bones of one well known to fame,

Within these vaults repose;

On history's page is graved his name

Ingrained with Erin's woes.Loved Taylor, Bishop

of renown,

His useful earth-course run,

Beside the Lagan laid him down,

The brighter life begun,

Stay, comrade, stay, nor grudge the tear

That by such tomb is shed;

Thy Welsh might well be buried here

Where sleep the glorious dead.

Light lie the turf on Walsh's grave,

By Dunum's whispering streams;

Thou moon, reflected in the wave,

Benignly fall thy beams;

Still shed a lustre round his head,

And through the long, cold night,

Above the clammy tombstones spread

A veil of silver light. |

Oh, raise thy voice,

famed Druim More,

And honour him now dead;

Thy choicest gems he held in store,

And walked, in deep things read-

Could trace thy life in days of old,

And all thy history tell,

Through age of bronze, or age of gold,

And words of ogham spell.His fall hath swept much

lore away;

For though oft pressed to write

Those thoughts he gave one by the way,

(All held so worthy light-

Ay, sometimes worth their weight in gold!)-

Still modesty was there,

To keep the treasured tale untold,

While we the loss must bear.

O rare collector, lying low!

All worthy of the bays;

Ye winds that round our Alick blow,

A solemn requiem raise:

The never-ceasing gleaner's gleaned,

By death's sharp scythe cut down;

From common life-walks, early weaned,

He worked, and won the crown! |

BIBLIOGRAPHY

A Ramble Through Dromore. John F. Mulligan 1886.

The Nation 13th May, 1843.

A Quaint Catalogue of Antiquities in the collection of Mr.

Welsh, Dromore. John Roggan 1840.

Rhymes Ulidian. J. W. Montgomery 1877.

County Down A Guide and Directory 1886 by George Henry

Bassett.

Will of Alexander Colvill Welsh dated 2nd February, 1876.

Will of Jane Welsh dated 18th January, 1905.

The Montgomery Manuscripts (1603-1706) Edited by Rev.

George Hill.

British Association for the Advancement of Science, Sept.

1852, Descriptive catalogue of the Collection of

Antiquities exhibited in the Museum, Belfast.

Welsh Collection, Summary list, National Museum of

Ireland.

Correspondence from Nessa O'Connor and Mary Cahill, Irish

Antiquities Division, National Museum of Ireland, Kildare

Street, Dublin 2.

Welsh/Dawson correspondence in the Royal Irish Academy,

transcribed by Winifred Glover, Ulster Museum, Belfast.

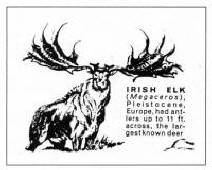

PLEISTOCENE PARK

The Story you have waited 12,000 years to hear!

The inability, or perhaps sheer cussedness, of one of my

siblings, to pronounce my church given name, resulted in

the title "Moose" being bestowed on me in my early

childhood. You will understand then, why my attention

was inevitably drawn to the words "Moose-deer" while

reading an extract from W. W. Sewards, "Topographica

Hibernia" 1795. The inability, or perhaps sheer cussedness, of one of my

siblings, to pronounce my church given name, resulted in

the title "Moose" being bestowed on me in my early

childhood. You will understand then, why my attention

was inevitably drawn to the words "Moose-deer" while

reading an extract from W. W. Sewards, "Topographica

Hibernia" 1795.

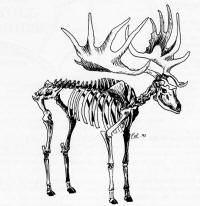

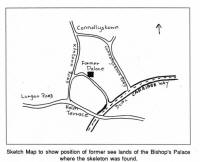

He records, that in 1783, a pair of

moose deer horns, measuring 14 feet and 4 inches from

tip to tip, were found on the see lands of Bishop Percy

of Dromore. Almost the whole skeleton of the animal that

wore them was unearthed and "computed to have been

almost 20 hands high".

Without modern scientific skills, Seward tells us that

it was unknown when these animals existed, but he does

say that their remains are usually found in the stratum

of marl covered by bog.

Marl is a term for clay containing the remains of shells

and it is now known that, after the last retreat of the

Ice from Ireland, there were numerous fresh water lakes

in which such clays were deposited. numerous fresh water lakes

in which such clays were deposited.

At this period Ireland was an integral part of Europe

and great deer roamed over the Continent from the

Atlantic to the Baltic. The skeleton was therefore most

likely that of an Irish Deer or Megaceros - akin to the

moose of North America. A continuing warming up of the

climate may have been the cause of the demise of these

graceful and well proportioned animals.

As the marls

dried out and became stickier they simply mired down in

them, or perhaps an epidemic distemper occurred. The

growth of forests may have sealed their fate, for while

sheltering their natural enemy, the wolf, they also

reduced the deer's feeding grounds by preventing them,

with their wide horns from entering. As the marls

dried out and became stickier they simply mired down in

them, or perhaps an epidemic distemper occurred. The

growth of forests may have sealed their fate, for while

sheltering their natural enemy, the wolf, they also

reduced the deer's feeding grounds by preventing them,

with their wide horns from entering. As this is now

within measurable time distance of the present day,

approximately 10,000 years ago, it has been suggested

that the first Irishmen may have seen the Great Deer

before it disappeared - The Gaelic term Danik-ailta

translates as wild-ox, but this may refer to another

species. On the other hand doubts have been expressed

that they lived long enough to be contemporaneous with

man. In any event Dromore man encountered their

remains over 200 years ago and according to S. Lewis in

his "Topographical Dictionary of Ireland" 1837 the

skeleton was placed in the Bishops palace where it was

carefully preserved.

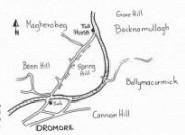

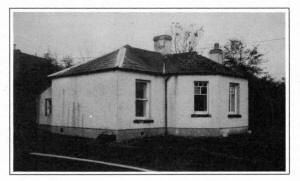

THE TOLL HOUSE

by

Rosemary McMillan

This

toll house was probably built in the 1740's This

toll house was probably built in the 1740's

The construction, by the Turnpike Trust, which existed

between 1733 and 1857, of a new stretch of road between

Dromore and Hillsborough, did not affect the site, or

the use of, the building. In the townland of Backnamullagh, the remains of this

turnpike road cross the present dual-carriageway from

N.E. to S.W. continuing on towards Dromore by way of

Mile Bush Road. -formerly the old Hillsborough Road. The toll house sits in the angle of this crossing and it

is thought to have continued to operate as such until

the Turnpike System was abolished in the 1850's. Unfortunately, we have omitted to preserve the Palace

and so our Dromore Megaceros has once more gone to earth

unless someone knows otherwise! -"Moose" McMillan.

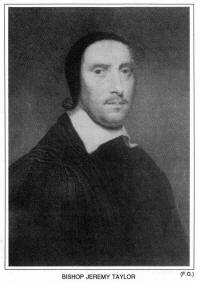

JEREMY TAYLOR

By Mark Hobson Jeremy Taylor was the third son of Mary

and Nathaniel Taylor, a barber to trade. He was born in

Cambridge and baptised there in Trinity Parish Church,

on the 15 August 1613. At the age of three years the

young Jeremy was sent to Grammar School in Cambridge.

Then at the age of fourteen he entered Caius College as

a SIZAR, and when he was twenty years old he obtained an

M.A. degree. As a youthful twenty-one year old a

dispensation was obtained in his favour and two years

before the Canonical age of twenty-three, he was

admitted to the Holy Orders. Jeremy Taylor then began to

preach with authority, power and sweetness. At that time

William Laud was Bishop of London, in 1663 he became

Archbishop of Canterbury. Jeremy Taylor continued with

his studies and preaching. On a friend's recommendation

he preached at Saint Paul's Cathedral in London where he

attracted the attention of the Archbishop of Canterbury.

He was then sent to Oxford where, under the guidance of

the Archbishop of Canterbury, he became a fellow of All

Souls in January 1636. Then in 1637 he was presented by

Bishop Joxon to the Rectory of Uppingham in Rutlandshire.

He was also appointed Chaplin to Charles I. While living

at Uppingham he made visits to Oxford and to the Court

of Charles I. On the 27 May 1639, he married Phoebe

Landisdale or Langsdale. In 1640 his great patron Laud

was sent to the tower for religious arguments with the

King and Parliament.

Taylor and his wife continued to live at the Rectory in

Uppingham, where Phoebe gave birth to a son. Sadly this

first child, William, died. From this quiet but un-safe

retreat he heard the distant mutterings and the loud

approaching roar of the troubles of the Civil War. The

Solemn League and Covenant had been formed in the year

of his appointment to Uppingham and the long Parliament

summoned. Jeremy Taylor carried on with his writing and

preaching. When the war began in 1642 he was writing

"EPISCOPACY ASSERTED", his home was pillaged and his

living taken from him. In the year 1642 King Charles I

read Jeremy Taylor's book prior to publication. He did

not, however, permit the writer to dedicate the book to

him. The book was called "OF THE SACRED ORDER AND

OFFICES OF EPISCOPACY" (1642). Taylor and his wife continued to live at the Rectory in

Uppingham, where Phoebe gave birth to a son. Sadly this

first child, William, died. From this quiet but un-safe

retreat he heard the distant mutterings and the loud

approaching roar of the troubles of the Civil War. The

Solemn League and Covenant had been formed in the year

of his appointment to Uppingham and the long Parliament

summoned. Jeremy Taylor carried on with his writing and

preaching. When the war began in 1642 he was writing

"EPISCOPACY ASSERTED", his home was pillaged and his

living taken from him. In the year 1642 King Charles I

read Jeremy Taylor's book prior to publication. He did

not, however, permit the writer to dedicate the book to

him. The book was called "OF THE SACRED ORDER AND

OFFICES OF EPISCOPACY" (1642). During the war, Taylor

marched side by side with Pearson and Chillingworth,

under the Royal Standard for King Charles I. He helped

to stir up the spirits of the fainting Royalists with

his sermons, as well as caring for the sick and wounded.

He was imprisoned twice during the Civil War, but was

treated with no great severity. Then in 1644, while

commanding an army for the King, he was defeated by

Laugharne, a Superior General. He then made his peace

with Parliament and received a Pardon. Whereupon he

retired to Carmarthenshire, where, being a celebrated

man of letters, he opened a school. His wife Phoebe died

in 1650. Now in retired life he was able to concentrate

on his writings. He was not entirely debarred from the

society of the good and the noble, for at Golden Grove,

in the same parish, there dwelt a nobleman who was kind

to the exiled clergymen. It was at Golden Grove that he

wrote his most famous works of all which were "THE HOLY

LIVING", "THE HOLY DYING" AND "THE LIBERTY OF

PROPHESYING". In time he then married Joanna Bridges a

lady of some property, and ceased teaching. Jeremy

Taylor was imprisoned in Chepstow because of his writing

about the church and religion. He was eventually

released from prison in the autumn of 1655. He spent a

short time at Mandinan and also some time in Wales,

where he wrote "A DEFENCE OF THE LITURGY", at the

request of the King. Then, in the year 1656 towards the

end of the Lord Protector's rule, Taylor went to London

where he was imprisoned in the Tower because of a

mistake which his publisher had made. They had rashly

prefixed to a collection of papers a representation of

Christ in the attitude of prayer. This offence was

punishable by a heavy fine or imprisonment. At this time

Taylor wrote his most elaborate piece of work, "DUCTOR

DUBITANTIUM", (a guide for the doubtful), which was a work

of some controversy. On his release from the Tower having

paid sufficiently for what he had written, he left England

in 1658.

He was encouraged by Lord Conway to settle in Ireland and

take up residence at Conway's princely mansion at Portmore

on the shores of Lough Neagh. Near Ballinderry lies the

ruined church and castle of Portmore. The castle of Portmore

was built in 1664 by Lord Conway on the remains of an

O'Neill Fort. Possession of the castle had then passed on to

his cousin Popham Seymour in 1683 and later to his brother

in 1699. He died in 1731 or 1732 and was succeeded by his

eldest son Francis, 1st Marquess of Hartford. The castle at

Portmore was demolished in 1761. The church at Portmore is

built on an artificial Island surrounded by a ditch and a

double hedge. Many people think that it is the "half ruined

church of Kilutagh" where Jeremy preached, while others

thinks that it is Templecormac. Even at Portmore under the

protection of Lord Conway he was not safe from arguments. In

1669 he was arrested and sent to Dublin for trial. The

charge brought against him was that he had used the sign of

the cross in administering the sacrament of Holy Baptism.

The charge was brought by a Presbyterian from Hillsborough

called Tandy. However, the authorities in Dublin did not

take the charge seriously and it was not long before Jeremy

Taylor was back at Portmore. The church in Dromore was the

"Church of Saint Colman" and it was attached to the

monastery. Under the charter of James I in 1609 it became

known as "THE CHURCH OF CHRIST THE REDEEMER", or,

"CATHEDRALIS CHRISTI REDEMPTORIS DE

DROMORE". During the rein of Elizabeth I the Cathedral

was in ruins and remained in that condition until James I

refounded the See by the Letters of Patent, which gave the

Bishops extensive land possession. In 1641 the Cathedral was

destroyed and it remained in ruins until 1661 when Charles

II gave Jeremy Taylor permission to rebuild the Cathedral.

In 1660 Jeremy had a complete change of fortune. He was

appointed Bishop of Down and Connor, and from his next visit

to Dublin in 1661 he returned as Vice-chancellor of the

University of Dublin. Also in January 1661 on the day of his

Consecration in Saint Patrick's Cathedral in Dublin, two

Archbishops and ten Bishops were consecrated by Archbishop

Bramhall. Jeremy Taylor preached the sermon on the day he

was consecrated. Bishop Lesley's episcopate in Dromore was

of too short a duration to effect any changes. In June 1661

Bishop Lesley was transferred to Raphoe, and he was

immediately succeeded in the administration of Dromore by

Doctor Jeremy Taylor. The Cathedral was in ruins when he

came to Dromore. At his own expense he rebuilt the cathedral

on the site of a Sixth Century monastic site. Local

whinstone was used in the building of the Cathedral. It was

one hundred feet long by twenty feet wide, (covering what is

now the Tower aisle). Jeremy Taylor also lived at

Hillsborough Castle with his friends the Hills. He used to

say his prayers in the fort and when the fort was remodeled

for family feasts and parties, an ornamental gazebo was

built in the middle of the North rampart in the Bishop's

memory. The windows resemble those of the parish church

which he had consecrated in 1663. Jeremy Taylor's career

was cut short because he contracted a fever while

ministering to a sick man on the 3rd August, 1667. He died

at his residence at Lisburn on the 13th August, 1667, and

was laid to rest on the 21st August, 1667 in Dromore

Cathedral by his friend

George Rust, although he had wanted to be buried in his

new church at Ballinderry where a grave had been

prepared for him. Taylor did not live to see his new

Church finished, in fact it was not consecrated until

the year after his death. Jeremy Taylor died aged

fifty-four. In his will he left ten pounds to the poor

in Dromore. He stated in his will "Bury me at Dromore".

He was survived by his wife Joanna and three daughters.

In the vestry at Dromore Cathedral there is a Paten and

a chalice both made out of silver. Jeremy Taylor's wife

Joanna presented them for use in Holy Communion. The

following inscription is engraved on both of them,

"IN MINISTERIUM S. S. MYSTERIORUM IN ECCLESIA. CHRISTI

REDEMPTORIS DE DROMORE."

"DEO DEDIT HUMILLIMA DOMINI ANCILLA D. JOANNA TAYLOR."

Jeremy Taylor and his

wife are buried in the vault underneath the chancel in

Dromore Cathedral. The Bishop's Throne in the Cathedral

is a memorial to Bishop Taylor. George Rust became

Bishop of Dromore after the death of Jeremy Taylor, who

had ruled the Diocese for just under seven years.

On Thursday evening the 5th June, 1958 the memorial

lecture to Bishop Taylor was inaugurated in Dromore

Cathedral. The instigation of this was the then Rector,

Canon R. W. Kilpatrick, who later became Dean of

Dromore. The memorial lecture in memory of Bishop Jeremy

Taylor, continues to be held each year. Jeremy Taylor

was a celebrated man of letters and he was also a Godly

man. He worked throughout the Diocese in helping the

poor and the sick. He also helped to rebuild the

churches and reassert the Christian faith among the

people in his Diocese.

LOCALS AT A PHEASANT SHOOT AT GILLHALL IN THE 1960's

including--Johnnie McConkey, George Martin, Albert

Gribben, Matt Forsythe, Frank Gibson, Victor Gibson,

Melvyn Martin, Malachy Gribben, Tom Dick, Jim Stronge,

Dicky Gracey, George Gracey, Cherry, Jim Agnew (now in

Canada), David McConkey, and John Curran(?).

BREWERY LANE

A BREWERY WITH A COVENANTING CONNECTION

by Robert McCollum

The

mention of Brewery Lane conjures up different images in the

minds of Dromore folk. Those who have come recently to live

in the town probably associate the name with the pensioners'

bungalows on either side of the street. But to Dromore

residents, born and bred in the district, the name bears

with it much wider associations. The

mention of Brewery Lane conjures up different images in the

minds of Dromore folk. Those who have come recently to live

in the town probably associate the name with the pensioners'

bungalows on either side of the street. But to Dromore

residents, born and bred in the district, the name bears

with it much wider associations. Before the bungalows were

erected by the Housing Executive in the 1970's the street

was much narrower and therefore appropriately designated, a

lane. On either side of this lane stood neat rows of

two-storey terrace houses. In the middle of the right-hand

terrace David Martin had a coal yard out of which he ran a

successful coal delivery business. Brewery Lane will

forever live in the memory of some Dromore citizens as a

source of employment. The lane terminates at the entrance to a hem-stitching factory which produced a selection of

linen tablecloths etc., which, not only supplied the local

market, but were exported to many parts of the world. With

the closure of the business in 1991, due to difficult

trading conditions, the factory buildings have been

demolished and the site is open for redevelopment. At

present the possible erection of a nursing home is being

pursued by a firm of developers.

to a hem-stitching factory which produced a selection of

linen tablecloths etc., which, not only supplied the local

market, but were exported to many parts of the world. With

the closure of the business in 1991, due to difficult

trading conditions, the factory buildings have been

demolished and the site is open for redevelopment. At

present the possible erection of a nursing home is being

pursued by a firm of developers. The name of this

particular street has always been associated with the place

of worship which has occupied a site adjacent to the factory

for a century. This is the Reformed Presbyterian Meeting

House, otherwise known as the Covenanters. The history of

this place of worship is very much associated with the

denomination to which it belongs. The Covenanters trace

their roots back to the Scottish Reformation. In the 17th

century the general population in Scotland, through

subscribing the National Covenant of 1638, covenanted their

church and nation to Christ. This concept of a church and

nation covenanted to Christ was anathema to the Restoration

King, Charles II, and from the outset of his reign (1660) he

embarked on a policy of persecution against those who

adhered to Covenanting convictions. After 28 years of bitter

repression, in which 18,000 suffered by death, banishment or

being reduced to absolute poverty, relief was obtained in

the Williamite Settlement of 1688-90. The Settlement,

however, gave no place for a covenanted church and nation

and a minority of the population remained separate from the

Revolution Church to maintain this vision. These are

covenanters who in Ireland and Scotland, and subsequently in

other parts of the world, were formed into the Reformed

Presbyterian church. Christians with covenanting

convictions have been associated with Dromore for most of

the history of the denomination's existence in Ireland. One

of the first Covenanting ministers ordained in Ireland was

the Rev. William Staveley and the Call that was issued to

him in 1772 came from the "Covenanted electors between the

Bridge of Dromore and Donaghadee in the County of Down".

Although resident in Knockbracken, Staveley exercised an

itinerant ministry which extended from Co. Down to the

Counties of Armagh, Monaghan and Cavan. The Covenanters in

Dromore would benefit occasionally from his ministry. At

this time in the history of the Reformed Presbyterian Church

small groups of Covenanters living in a locality were formed

into Societies for mutual spiritual support and fellowship.

Dromore was no exception and the first record of these

Societies being involved in Calling a minister of their own

is found in the Minutes of the R. P. Synod for 27th May,

1812:

The Minutes of the Southern Presbytery report

that the Societies in the vicinity of Dromore,

hitherto unconnected with any congregation had

become attached to the congregation of Rathfriland,

which Congregation had presented a Call to the Rev.

John Stewart - that he had accepted of it and was

installed to the Pastoral Charge of the congregation

of Rathfriland and Dromore on Monday, 25th May,

1812.

This arrangement with Rathfriland existed until the death

of Mr. Stewart in 1837. This occurrence appears to have

prompted the Dromore covenanters to Call their own minister.

Having called licentiate James Steen this young man was

ordained to the gospel ministry in Dromore on 4th June,

1839. This settlement in Dromore may have been part of the

motivation which caused Rev. James Dick, at the Synod

meeting in July 1839, "to give notice of motion for the

formation of a Fifth Presbytery, comprising the

congregations of Dromore, Bailiesmill, Knockbracken, 2nd

Belfast and Ballyclare". Dissension in the Synod of 1840 and

the subsequent departure of the Eastern Presbytery to form a

separate denomination - the Eastern Reformed Presbyterian

Church - caused Mr. Dick to withdraw his motion. Although no

details are recorded of the size of the congregation in 1839

we can assume it bears some relation to the statistics given

for Dromore in 1854. The Drornore congregation consisted of

2 elders, 3 societies, 14 families and 45 members with an

annual income for congregational purposes of �16-4-0 and

�2-3-0 for missions. Mr. Steen's connection with the

congregation was short lived for in the report of the

Southern presbytery to Synod in 1840 the following paragraph

is included:

Presbytery are sorry in having to report, that at

its last meeting, the Rev. James Steen petitioned

for a disannexion from the congregation of Dromore,

as its pastor, on the ground of the unpromising and

hopeless state of the congregation. The Presbytery,

before taking up the case, thought it advisable to

hold a visitation Presbytery, at Dromore, for the

purpose of investigating more particularly the state

of the congregation, in order to decide on this

matter: this meeting is to be held on the first

Tuesday of August next.

At this meeting Mr. Steen resigned. He joined the General

Assembly the following year and was installed in Clonduff

Presbyterian Church on 21st June, 1842 where he ministered

for 39 years. After Mr. Steen's ministry Dromore never had

its own minister again and had to depend on pulpit supply,

sometimes on a very irregular basis. For example, the

Southern Presbytery report to Synod in 1843 reads:

The vacancies of Grange and Dromore, and the

Society in Dublin, have received some supply of

ordinances from us during the course of the past

year.

Better provision was made for Dromore in 1845 as is

reported by the Presbytery to the Synod.

According to an arrangement approved of by

Presbytery the vacancy of Dromore has been taken

under the pastoral care of the Rev. J. W. Graham,

for one year, and supplied with sermon every fourth

Sabbath.

Mr. Graham was the minister of Bailiesmills congregation

who, with his congregation, was received into the Southern

Presbytery from the Eastern in 1840. This arrangement with

Mr. Graham seems to have continued until his death in 1862

when Bailiesmills returned to the Eastern Presbytery.

Recognition is given to Mr. Graham's service in Dromore in

the 1850 Presbytery report.

The vacant congregation of Dromore has enjoyed

preaching about half time during the past year from

members of Presbytery and Licentiates, including the

ministerial labours of Mr. Graham one Sabbath in the

month, although no pastoral relation, strictly

speaking, has as yet, been formed between him and

that people.

At this time the Presbytery apparently had grounds for

encouragement in the work among the Dromore Covenanters.

Excerpts from the reports to Synod in 1851 and 1853 give

reasons for optimism.

Presbytery has under its care the vacancy of

Dromore, which has been supplied with preaching

about half-time. The adherents to our cause in that

place although not numerous appear steady, not

withstanding the many difficulties with which they

had to contend for many years. (1851) During the

past year the vacant congregation of Dromore has

been supplied with a preached gospel almost every

alternate Sabbath; the members in that locality

continuing warmly and steadfastly attached to a

covenanted cause and testimony, and giving regular

attendance on the ordinances of Divine institution.

(1853)

The tone of Presbytery's report in 1856 is altogether

different.

Dromore has received as formerly the preaching of

the Gospel every third Sabbath, and the ordinance of

the Lord's Supper was celebrated there on the third

Sabbath of August last, not without some evidences

we trust of the presence of the Master of

Assemblies; still, with sorrow we are compelled to

state, that our cause does not seem to be making

much progress in this place, there appears to be a

considerable amount of deadness, and besides some of

the most active and influential members of our

Church there, have in the inscrutable Providence of

God been removed by death, thus leaving a void not

easily supplied. Still we know that the residue of

the Spirit is with God, and he, by breathing on even

dry bones, can cause them to live.

The

witness, however, continued and from church records it

appears the present meeting house in Brewery Lane came into

the possession of the Covenanters in 1881. The property was

sold by John and Robert Harrison to the church which was

represented by John Wright Hawthorne and Thomas Hawthorne of

Fedney, Josiah Archer of Ballymacbrennan (farmers) and John

McEwen of Dromore (tailor). The

witness, however, continued and from church records it

appears the present meeting house in Brewery Lane came into

the possession of the Covenanters in 1881. The property was

sold by John and Robert Harrison to the church which was

represented by John Wright Hawthorne and Thomas Hawthorne of

Fedney, Josiah Archer of Ballymacbrennan (farmers) and John

McEwen of Dromore (tailor). In 1898 Dromore was

transferred to the care of the Eastern Presbytery and became

associated with the work of the Dromara congregation. The

monthly service became the responsibility of the Dromara

minister. This arrangement worked well for almost a century

until in 1990 a committee of the Eastern Presbytery was

given the responsibility for oversight and services are now

being held weekly. Whatever the future of the Covenanter

witness in Dromore it is likely to continue in Brewery Lane

for the fellowship has had plans drawn up to erect a new

meeting house when the site is redeveloped. Research into

Brewery Lane has not revealed anything about what gave the

street its name. Obviously there must have been a brewery

there at some time. Did the Harrisons produce beer in the

present meeting house before it became a place of worship?

Might there even be an old still under the floorboards? Some

of the readers of this journal may be able to reveal some

information so that the mystery of the brewery in Brewery

Lane may finally be solved.

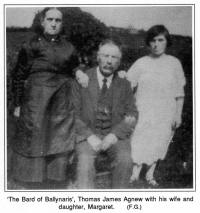

MY GRANDA AGNEW

by Sam Johnston

As

my paternal grandfather died before I was born, I somehow

felt shortchanged when I discovered that other boys had two

grandfathers. As

my paternal grandfather died before I was born, I somehow

felt shortchanged when I discovered that other boys had two

grandfathers. Perhaps that was why I cherished and adored

my grandfather Thomas James Agnew and when he came to visit

his daughter, my mother, I would get out my little green

stool and sit between my father and him, as quiet as a

mouse, for children in those days were seen and not heard,

especially six year olds like me. I hung on their every

word and yearned to be grown up like them and to experience

the things they talked about. Things like gardening,

fishing, greyhound racing, rabbit hunting and canary

breeding. The finding and dressing of Blackthorn sticks.

Playing marbles on the public road by men of mature age in

the long summer nights. Swimming in the Lagan. And the

doings and happenings and goings on in their places of work.

To me it was magical and to be allowed to sit up late

instead of being chivvied to an early bed was a bonus beyond

price. The older I grew so grew my appreciation of old

Granda. He was a very wise man whose council was much sought

after in short, he was a sage. Perhaps his profound

knowledge of the Bible had a lot to do with it. He was

born around 1850 and was a handloom weaver plying his trade

from his home in the Kilntown district. He would tell of

weaving till 3 o'clock in the morning because there was no

food in the house to feed his growing family. Then, putting

his bolt of cloth on his shoulder, he would walk ten miles

to Lurgan, to the depot where he received his wages. The

journey home again to Dromore seemed much shorter with only

his money to carry, and with a visit to some shops, which

were just opening at that hour, he would return home with

much needed foodstuffs for his famished family. Were those

the good old days?. After rearing his family in the

Kilntown, he removed to Ballynaris Hill and with the

handlooms becoming obsolete he found work as a roadman, or

surface man as they were called, whose job it was to keep

the roads free of potholes, cut the grass verges and

overhanging hedges, clean out sheughs and gratings to avoid

flooding, and while there wasn't the same amount of litter

that disfigures our streets to-day, there was always ample

supplies of manure from the "exhausts" of horse drawn

vehicles to be swept up. It was a retrograde step when the

councils discontinued the use of these surface men and

replaced them with a mechanised gang of men who were rarely

seen in operation! Consequently our roads to-day are a

danger with head high vegetation obscuring the view of

motorists, especially when entering main roads from by-ways.

It is high hypocrisy on the government's part to implore the

public to "KEEP BRITAIN TIDY" when they keep their

thoroughfares in such a disgraceful state. Roadmen were

plodders regarding work, and strength had to be conserved

when wielding scythes, bill-hooks, sickles and spades in the

execution of their jobs. So it was said by the cynics that a

sure cure for warts was to immerse them in a roadman's

sweat, implying that it was a very scarce secretion!

When Granda retired from work he removed from Ballynaris

Hill to live with his spinster daughter, in a little

whitewashed cottage in Ballymacormack, access to which was

down a rough track across two fields. I well remember the

fragrance of the old cabbage roses which grew in profusion

right up to the low thatch, and a huge stone on which we sat

outside the door and which I associated with the song about

"The stone outside Dan Murphy's door". I was not alone in

my memories about this old place, for my sister Margaret

reminisced time and again how she would be invited by her

aunt, after whom she was called, to stay for a few days when

she was a schoolgirl. She would sit on the big stone which

she imagined was a throne, and she a little princess, until

Aunt Maggie would call her in for her tea. While there was

nothing "fancy" on the table, they being, like everyone

else, poor people, she did have a whole egg to herself which

was akin to a banquet! It was served with three condiment:

salt, a little butter, and a large dollop of pure love for a

little niece. When I reached my teens Granda was long

dead. By that time I had developed a love for poetry and had

attempted to put together some lines of my own. You can

imagine my delight when I first learned he had been a poet

of some note himself. his son, my Uncle Sam, would recite

snippets of them for they were chronicles of happenings and

events that occurred during his lifetime. Like, for

instance, a big stag hunt that traversed many districts

before being ended in Lisnashanker, as described in the

poem:

In the townland of Shanker

We forced him to turn,

He was surrounded by men

And caught near the burn.

And there was another, telling of two rascals who stole

six hens from a widow near Magherabeg. The astute woman went

to Lisburn the next day and her "hunch" proved correct, for

she found the robbers trying to sell her hens which were

trussed up in a potato basket. She confronted them and they

took to their heels and ran off, or as Granda wrote:

"Give back, give back my

fowl," she cried!

"Or on the police I'll call,"

And they ran home by the

Longstone

Leaving basket, fowl, and all.

Just two years ago I was given copies of two of his poems

by a relative, and I treasure them greatly. The first tells

the true story of an attempted murder on the Lurgan Road at

Coolsallagh around the 1930's when a married man took a

crazy notion for a young woman who, quite rightly, spurned

his advances. This unrequited love curdled his passion into

an insane hatred, and one Sunday evening as she cycled to

church he lay in ambush and blasted her with a shotgun as

she passed. The victim fell to the ground and the would-be

assassin broke from his cover and bolted madly across the

fields to his home, not far away. The crows had hardly

settled round their nests in Gillhall demesne after the

first explosion till they were airborne again in a raucous

black flailing of wings as the sound of a second gunshot

rent the air as the madman blew himself into oblivion. The

shock and terrible tragedy on that tranquil Sabbath evening

is vividly portrayed in Granda's poem:

Assist me now you

Muses

And send me no excuses,

My weary mind confuses

As I lift my trembling quill.

To write this dreadful action

That has caused great distraction

Done in Gillhall direction

Near Ballynaris Hill.In the year of nineteen

hundred

and twenty nine remember,

The month it was September

upon the fifteenth day.

It was the Sabbath evening

The church bells they were ringing

When the vile assassin

Tried to take two lives away.

The evening sun was glowing

And to church the girl was going

The murderous villain knowing

To meet her on the hill.

Without a word of warning

All death and sorrow scorning

His firing of a shotgun

Intended her to kill. |

When the police

went to his dwelling

Got no answer to their calling

The sight it was appalling

When they broke down the door.

A deed of cruel vengeance

Had then been comprehended

His body it lay motionless

Upon the kitchen floor.They found that he was

dead

With a gunshot through the head

And that he pressed the trigger with his toe,

His skull lay on the ground

In splinters to be found

And the blood around the body it did flow.

The lady's name to mention

It is not my intention

It's beyond my comprehension

My motive or design.

It was the work of Satan

that great incarnate spirit.

It would have been no other

Neither human or Divine. I will give you this

advice

Strive always to be wise

By the wiles of Satan

don't be led astray.

A warning take in time

And ne'er commit a crime

For we can't escape the general Judgement day. |

When one reads poetry of such quality and then

reflects that the writer had received only the very

minimum education back in the 1860's one can only

conjecture what heights his latent talent could have

scaled had he been given the further education

available today. There is the other side of the

coin which shows some students who are to-day

attending universities but lack the basic respect

for other people and their possessions. I have

witnessed at first hand brand new flats, inhabited

by said students, reduced to stinking hovels with

excreta encrusted toilets. The space under the beds

being used as rubbish dumps for their unspeakable

litter, and the panels of inside doors kicked into

firewood.

Granda would have directed them to the chapter

and verse which warns of the profligacy of casting

pearls before swine. Had he been around to-day he

would have been the first to admit that with his

free access to all this knowledge, modern man has

advanced with giant strides DOWN the hill of

Uprightness.

One of the great money spinners of to-day is the

sale of refreshing drinks. In Granda's time the poor

mans thirst quencher was Adam's ale obtained from a

cool spring well. In the very hot weather the sure

way to allay a thirst was to add a handful of

oatmeal to a can of spring water, the result being a

kind of uncooked porridge which slaked parched

throats indefinitely. It was called sowans and when

`sowans' were mentioned in our house, someone was

sure to recount the story of the summer evening when

three of Granda's daughters were sent some length to

a neighbouring farm for a large can of buttermilk.

In those days women wore monstrosities of torture

called `stays,' the tension of which was controlled

by a type of hook and eye fastener on front, and

laced with a strong cord behind. What with the long

walk, the sultry air, and the tight enveloping

stays, the more plump of the sisters was dying of

thirst. Fortunately, there was a large bucket of `sowans'

available at the farm, and the water level was

lowered several inches, and then several inches

more, before they started on the return journey. The

plump one had only gone a short distance when she,

complaining about her continuing aridity, had

recourse to the can of buttermilk, part of whose

contents became another ingredient in what was fast

becoming a gaseous cocktail. In fact her sisters

could hear the rumblings of the fermentation taking

place inside her bloated body and fearing that the

imprisoned gases would make her airborne, took her

by the hand lest she floated over the hedge! At

last they reached the haven of home and immediately

to their bedroom where the plump one- who was

getting plumper by the minute-was divested of her

outer clothing and the task of unhooking the stays

was begun, but it was beyond their combined powers!

Granda's aid was then sought but all the pummelling

and wrestling only increased the pressure like an

agitated bottle of champagne. There was only one

thing for it. Granda took out his penknife and cut

through the retaining cord on the back of the stays.

Mercifully there was no-one standing in front of her

for the stays catapulted forward like a projectile,

pulverising the plaster on the bedroom wall! Later

when the plaster was repaired it served as a

memorial of `The Night of the Sowans'. Alright! I

may have embellished and embroidered a little in the

telling of it, but in the main the tale is true.

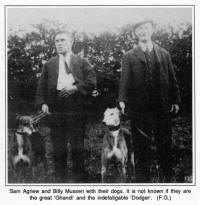

The second poem I mentioned earlier was in much

lighter vein and concerned a greyhound owned by

Granda's son Sam and called "Ghandhi" after the

illustrious Indian statesman who `shook the world'

with his non-aggression and peaceful policies.

Greyhound racing - if not the sport of kings - was

the poor man's pastime and a grand old character

called Billy Mussen owned a field where now stands

the houses of New Cottages and Wallace Park. This

field was dubbed `Mussen Park' and greyhounds from

near and far competed there. The track was about 150

yards long and lay up a gently sloping field which

afforded a good test for stamina and speed. The

starting box was hand-operated and a strand of

bull-wire stretched from there to the finishing

line. The stuffed pelt of a rabbit was fastened to a

piece of board about 4" x 12". Two metal rings

through which the bull-wire ran were affixed to the

board. A strong linen cord was tied to the rabbit

and the other end was attached to the rear wheel of

a specially adapted bicycle at the top of the field.

When the gear wheel of the bicycle was cranked by

hand the linen cord was wound onto the rim of the

rear wheel and the rabbit would come hurtling up the

field, bobbing along like the real thing, with four

greyhounds in hot pursuit! As far as we small boys

were concerned the `Star of the show' was called

Jack `Snick' Magee, the local blacksmith. He it was

who operated the winding apparatus, and I can still

see his brawny arms cranking like mad as he strained

to keep the rabbit ahead of the greyhounds! While

most small boys wished to be engine drivers on the

Great Northern Railway, we yearned to emulate Jack

Magee.

Quite large crowds would come to these races and

would align themselves on either side of the

bullwire, forming an avenue up which the dogs raced.

Billy Mussen had a four-footed `flying machine'

called `Dodger'. Like many a good dog he would be

taken to compete at other free-and -easy race tracks

and entered under another name so as to attract

greater odds in the betting. However, the fact that

he had one lop-ear was the `give away' that blew his

cover and warned the cognoscenti that he was indeed

the great `Dodger'.

A tale attributed to Billy, and I can fancy I see

the gleam in his eye, and the grin lurking beneath

his ragged moustache, as he would tell the tale of

how a big storm blew down the shed which housed his

big billygoat. Until he got his shed repaired, and

because the weather was extremely cold, he kept the

goat in a spare bedroom at night where, according to

Billy, he got the odd mouthful of straw out of the

old mattress. News of the goat's habitation came to

the ears of the priest and he inquired of Billy if

it was true. Billy assured him that it was, to which

the priest asked aghast,"But William, what about the

smell"? "Ach sure Father" replied Billy, " the old

goat soon got used to it!"

But now to Granda's second poem. Like Ghandhi the

politician and statesman, Granda saw that Ghandhi

the greyhound would also have his niche in history

when he penned the following poem about his exploits

when he won a big race at Dromara.

Come all

you young sportsmen

To my ditty attend

Who like greyhound coursing

And have money to spend

If you bet upon Ghandhi

You will never complain

I am told that his owner

Lives in the Cross LaneLast boxing

Day morning

Some sportsmen did go

To the town of Dromara

Their prize dogs to show

And to carry the laurels

In triumph away

But when they met Ghandhi

They met with dismay The betting was

even

To the coursing begun

From that to the finish

You gave two to get one. |

And when the boys saw

him

they knew what to do

For they all backed on Ghandhi

that was owned by Agnew.For this

Ghandhi's a dog

of great fame and renown

Well known by all sportsmen

in the County of Down

His equal for coursing

no-one ever saw

Since the Rose of Old England

or bold Master McGraw For when Ghandhi

started

Away he did fly

As fast as the lightening

He passed them all by

He has conquered before

and will conquer again

And has carried the laurels

Home to the Cross Lane. |

Can I say in conclusion that I think my granda, like Ghandi, was `some

pup' too

|