|

IN THE DAYS OF JAKEY

HAMILTON

By John McGrehan

Early in the 1870's a man named John Hamilton later known

as Jakey Hamilton came to Dromore. He came to work his

patents in hemstitching and embroidering for the sole use of

Henry Matier & Co. of Belfast. He had several patents in

this particular field of activity. He made a beginning in

rooms in Market Square but after a time he purchased some

ground in Meeting Street on which he built a factory, which

extended from the street to the edge of the River Lagan, in

which he continued to work his patents and to improve

hemstitching machinery.

The factory was considered to be a most modern one for

it's time, being built with scotch brick and bordered with

coloured brick in Georgian style. Some time about 1900 this

factory was destroyed by fire and it would appear that only

the gable at the side of the river was left standing. In

later years, when alterations were made to windows, small

portions of burned beams were discovered in this section of

the building. When the factory was being re-built it is

thought that the brick used came from the brickfield which

was only a short distance from the factory site.

During the late 1880's it is recorded that a mill in

Dromore was owned by E. McCartney. This mill was situated

off Church Street at the bottom of what is now known as Mill

Lane and was powered by a water wheel and up to some years

ago this old wheel could still be seen from Downshire

Bridge. The water to run this wheel came by way of a race

which started from the Weir Stones down by the side of a

field at the Mount, passing by the side of Graham's Yard,

along the bottom of Mount Street, right across the side of

the Square down to the mill. After powering the wheel the

water then re-entered the River Lagan. Furthermore, the

portion of the original race that was in Mount Street was

open with a well on each side, the Urban Council had it

covered over and it was used for car parking.

At the beginning of the century the mill buildings, race

and adjoining ground were taken over by Mr. Hamilton who

paid a rent of �72.00 per year. There must have been some

vacant ground convenient to the mill available for building

as some shops were erected in Church Street/Bridge Street

and it is believed Mr. Hamilton was responsible for building

these as he was a great person for erecting buildings with

flat roofs! It is thought that this was to save rates.

Before we leave the buildings in Church Street an amusing

tale is told of the building at the corner of Church

Street/Bridge Street. It is said that "the powers that be"

asked Mr. Hamilton to have the building erected with a

sloped corner but unfortunately they could not agree on the

amount of money needed to do this. Mr. Hamilton had the

first storey made with a square corner and from the second

story up the building was made with a sloped corner the way

that the Authorities wanted the building done in the first

place, so there were awkward people even in those days!

Mr. Hamilton must have been a great engineer in his time

as he planned to have the factory erected in the early

1900's to be powered by water. About 200 yards down from the

start of the original race he had this race tapped and

brought the water from the race over the river by means of a

wooden aqueduct he caused to have erected. Mr. Hamilton

owned land on which he had built Otter Lodge and this

aqueduct was joined to a race he had made at the side of

Otter Lodge grounds to the factory. The water from the race

came downstairs into a portion of building built at the side

of the factory in which were placed 2 turbines through which

the water went into the river. One of these turbines

supplied power for the machinery and the other turbine used

to power a dynamo to generate electricity. The turbines were

supplied by John McDonald of Glasgow and the dynamo by

Geoghegan of Banbridge. The flow and supply of water in the

race was regulated by means of sluices. Some yards down from

the River Lagan at the side of Weir Stones where the race

started, there was a large sluice. During the summer and at

times when there was a scarcity of water this sluice was

closed down at evenings to let the water gather and when it

was opened in the morning there was mostly sufficient water

to keep the turbine providing power for the factory all day.

In the original race just down below where the aqueduct

joined the race there was a sluice. The purpose of this

sluice was two-fold; one to stop the water continuing down

the original race and directing it into the aqueduct and

second if there was too much water going into the aqueduct

to open this sluice so that the surplus water could escape

down the original race. Then there was a sluice at the

beginning of the aqueduct and when this was closed it meant

that no water could get into it so that necessary renewals

and repairs could be carried out. There was also a sluice

some 30 or 40 yards from the factory which was opened every

night to let the water from the race go direct into the

river and thus preventing the race overflowing and flooding

into the factory. The new factory that was built early in

1900's was a three storey building and was one of the first

in the country in which machines were power driven and

lighted up by electricity.

The power provided by the turbine was on the whole most

successful and provided power for some 60 to 90 machines.

The only time that the machines were not going as quickly as

required was when there was a flood in the river and this

prevented the water from the race getting through the

turbine and back into the race as quickly as necessary, but

this did not happen very often! When this did happen the

girls working the machines soon let it be known and shouted

"more steam!" The turbine used to generate electricity was

most successful, the only problem was in turning on this

turbine it was important not to turn it on to quickly in

case some of the bulbs would be blown.

The ground floor of the building was used for laundering

the goods and was most complete and up to date as there was

a power driven washing machine and a large smoothing

machine. There was also a section of the room used for hand

smoothing and for making up, boxing and parcelling the goods

ready for dispatch.

In the middle storey of the factory the machines were

placed and worked by the girls.

The top storey of the factory was used for cutting the

goods ready for stitching and printing ready for embroidery.

A section of this room was used for packing the goods into

cases and cartons ready for despatch all over Great Britain

and sometimes some went as far as Canada and Australia. On

this top room was also a section for the offices.

The products of this factory were a large selection of

household goods such as bedspreads, sheets, tea cloths, tray

cloths, table cloths, valances, pillow cases and bolster

cases.

John Hamilton lived in Otter Lodge which he had built,

probably with brick from the brickfield across the road. In

the factory there was a spring and he had the water from

this spring piped up to his residence and by means of a pump

powered also from the turbine a supply of water was pumped

up to the house when required.

At the beginning this firm was known and run under the

name of John Hamilton Hemstitcher and Manufacturer of Fancy

Goods with the address of The Factory, Dromore.

|

Trade Notice.

Messrs. John Hamilton & Co., The Square, Dromore.

Every housewife loves fine linen,

and on the right selection depends much of her

future comfort. If she deals with Messrs. John

Hamilton & Co., The Square, Dromore, she will be

assured of the utmost value at extremely low prices.

Everything in Linen for the household can be

procured here, sheets, pillow cases, table cloths,

etc. all of the finest quality. |

In 1908 a firm was floated under the name of Hamilton

McBride & Co. Ltd. to take over the business of John

Hamilton with John Hamilton as Managing Director, his

daughter Nellie as secretary, other shareholders being

members of his family and James Crossin McBride who resided

at York House, Dromore. Over the years the shares changed

ownership but the firm continued to operate in Dromore until 1968 when it moved over to Manchester and is still

producing and selling household textiles up to the present

time.

It is said that John Hamilton was a most eccentric man

and was related to the Nelson family who had a General

Drapery, Boot Warehouse and Pawnbroking establishment in

Rampart Street. The story is told that Joe Nelson wanted to

borrow hedge clippers from John Hamilton and sent a boy up

to ask for them. The boy went up and said "Jakey, Mr. Nelson

wants the loan of your hedge clippers", to which John

Hamilton replied, "Tell Joe Nelson that Mr. Hamilton is

using the hedge clippers!"

Many stories were told about John Hamilton but after a

very busy and eventful life he died on 27th January, 1919,

and is buried in First Dromore Presbyterian Graveyard.

|

Oshawa,

Ontario,

Canada, LIG 1133

Mr. Jim Hutchinson,

28 Milebush Road,

Ballymacormick, Dromore,

April 28, 1994

Co. Down, N. Ireland.

Dear Mr Hutchinson,

I have just read Volume 3 Journal and thoroughly

enjoyed it. These books about Dromore are so

interesting, I hope there will be many more.

The Editorial Committee may find the enclosed

story interesting, and if so, have my permission

to print it.

Sincerely,

Mrs Norma (McClughan) Kerr |

* * *

THE

GRAVE SNATCHER

By Norma Kerr

The late Richard John Mercer and his spinster sister

Mary, used to own a farm near the top of the Diamond Hill in

Skeogh - I think a Mr. Gribben lives there now. Richard John

died in the late 1940's when he was in his eighties. During

the last few years of his life, he was very frail. My

father, the late Thomas John McClughan used to go to his

house twice a week to shave the old gentleman. As a

youngster, I often went with my father to watch Mr. Mercer

get his shave and I heard many stories. Here is one of those

stories which is still very vivid in my mind today.

This must have happened in the late 1880's when Richard

John was a young man. Someone in the neighbourhood had died

and was buried in First Dromore Graveyard. I can't remember

who the person was or if they were male or female. The day

following the burial, it was discovered that the grave had

been re-opened, the coffin empty, and the corpse gone. The

next day, before dawn, Richard John and a relative of the

deceased set off in a horse and cart for Belfast. Upon

reaching Belfast, they made their way to the docks where

they saw a man carrying a sack over his shoulder. Richard

John recognised this man, his name was McNutt. When Mr.

McNutt saw the two gentlemen, he immediately dropped the

sack and ran. Sure enough, inside was the stolen corpse.

Richard John and his friend did not return the stolen body

to First Dromore graveyard, but had it buried in a graveyard

outside Belfast. This Mr. McNutt lived half way along a lane

at the bottom of Diamond Hill - the late Mariah McClune

lived in the same house later. I'm sure the house must be in

ruins by now.

The grave snatching Mr. McNutt was never seen or heard of

again.

In the olden days, bodies were often stolen from graves

and sold to medical institutions, hospitals, and doctors for

research. Some were shipped over to England. If you take a

walk through some of the old graveyards today, you can still

see tall pointed railings around old graves - these were put

there to prevent such crimes.

Holidays early in the century

by Muriel McVeigh

Vacations play such an important part in modern living

that it could be difficult to imagine there was a time when

leaving home for a break from work was the exception rather

than the rule.

The

Great War, lasting from 1914 through to 1918, occupied

people's minds throughout the United Kingdom of Great

Britain and Ireland, and scarcity of resources, surely shut

out the idea of holidaying abroad, and I should think a day

to Newcastle, Bangor, Warrenpoint or Portrush fulfilled the

wishes of people to cast care aside for a while. The Great

Northern Railway Company simplified the means of getting to

the seaside from Dromore and it was not unusual to meet

local business people strolling on the promenade in

Newcastle any Thursday afternoon in the summer, taking

advantage of the facility on early closing day. Longer

holidays were geared to school closings which were much more

meagre in the twenties, thirties and even forties and

fifties than they are in the nineties. The

Great War, lasting from 1914 through to 1918, occupied

people's minds throughout the United Kingdom of Great

Britain and Ireland, and scarcity of resources, surely shut

out the idea of holidaying abroad, and I should think a day

to Newcastle, Bangor, Warrenpoint or Portrush fulfilled the

wishes of people to cast care aside for a while. The Great

Northern Railway Company simplified the means of getting to

the seaside from Dromore and it was not unusual to meet

local business people strolling on the promenade in

Newcastle any Thursday afternoon in the summer, taking

advantage of the facility on early closing day. Longer

holidays were geared to school closings which were much more

meagre in the twenties, thirties and even forties and

fifties than they are in the nineties.

Primary schools were shut for a week or ten days at

Easter and Christmas, a week at potato harvest time and five

weeks between July and August. Money to spend on hotel or

even boarding house residence was not readily available but

some boarding houses in Newcastle provided a kind of

self-catering arrangement. Holiday makers could obtain a

room and the cooking services of the landlady while

providing the food for themselves-a useful arrangement

particularly for the families of farmers when butter, eggs,

bacon, potatoes and other foods could be brought from home,

and a week or more at the seaside became feasible. In those

days the children were often packed off to stay with Grandma

for the summer holidays which made a nice change especially

if Grandma lived some distance away, - in my case ten miles

was quite a distance and many of my early y ears

summers were spent like this. ears

summers were spent like this.

In the twenties the Boy Scout and Girl Guide Movements

were growing. Summer camps for all ages of youth became

popular, when bell tents were erected, palliases were filled

with straw from some nearby farmyard to prevent the young

body having to sleep on bare ground and in some cases have

the company of swarms of earwigs. Primitive kitchens were

set up to enable the youth to practise their cooking skills.

During the thirties ownership of motor cars increased

dramatically and influenced the holiday making propensities

of the populace. Soon Donegal, Galway, Killarney or Cork

were almost as accessible as Portrush or Ballycastle and

indeed the idea of leaving the island for a trip abroad

emerged.

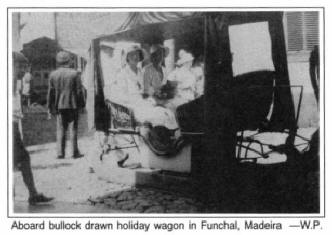

In the mid thirties a friend invited me to accompany her

on a " Mediterranean Cruise" and the memories of that

twelve-day holiday are still quite vivid. �1 a day in 1994

may seem a very small sum to pay for a holiday into the sun,

with wonderful food and the opportunity to visit such places

as Cadiz in Spain, Ceuta in Morocco, Funchal in Madeira and

Lisbon in Portugal before recrossing the Bay of Biscay and

the Irish Sea. However that constituted more than a month's

salary for me then. Add to that the need for a comprehensive

wardrobe of suitable clothing to cover the many occupations

aboard ship and the trips ashore, and three month's salary

was required.

We

joined

S.S. Melita which hove to at the mouth of Belfast Lough,

having come from Scotland, via tender from Belfast Docks.

The excitement was immediate though the next twenty four

hours were occupied in finding our sea legs before joining

in all the activities on board such as deck quoits and other

games, swimming in the pool, sun-bathing, after dinner

dancing, orchestral concerts or film shows. Outward bound

the first port of call was Cadiz in south-west Spain where,

with the help of tugs, Melita tied up to the quay early in

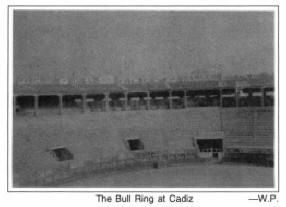

the morning. The day was spent visiting impressive churches,

and doing a little shopping. Initially we were taken to a

bullfight arena where we were amazed at the immense size

with its tiered seating. The torero, however, being confined

to Sunday action, and this being midweek, we were spared

having to watch the gory spectacle, and were satisfied to

inspect the elaborate costumes of the toreadors, picadors,

and matadors accompanied by a guide's description of the

noise, dust and gore, which marked the Sunday afternoon

entertainment of the local populace. The day ended with

dancing at a We

joined

S.S. Melita which hove to at the mouth of Belfast Lough,

having come from Scotland, via tender from Belfast Docks.

The excitement was immediate though the next twenty four

hours were occupied in finding our sea legs before joining

in all the activities on board such as deck quoits and other

games, swimming in the pool, sun-bathing, after dinner

dancing, orchestral concerts or film shows. Outward bound

the first port of call was Cadiz in south-west Spain where,

with the help of tugs, Melita tied up to the quay early in

the morning. The day was spent visiting impressive churches,

and doing a little shopping. Initially we were taken to a

bullfight arena where we were amazed at the immense size

with its tiered seating. The torero, however, being confined

to Sunday action, and this being midweek, we were spared

having to watch the gory spectacle, and were satisfied to

inspect the elaborate costumes of the toreadors, picadors,

and matadors accompanied by a guide's description of the

noise, dust and gore, which marked the Sunday afternoon

entertainment of the local populace. The day ended with

dancing at a beach hotel and our departure to Ceuta, our next port of

call, took place shortly after midnight.

beach hotel and our departure to Ceuta, our next port of

call, took place shortly after midnight.

The visit to Ceuta included a bus run to Tetuan where we

were escorted through the Arab souk where all kinds of

exotica were on sale and the handcrafted leather bags

appealed to me. The lovely Portuguese island of Madeira was

the highlight of the cruise-the sea in Funchal Bay had the

bluest water I had . ever seen. Everywhere on the island

there were flowers. I was tempted to spend more money than I

could afford on the fine hand-sewn linens. I had to be

satisfied with a very small piece in the shape of a romper

suit for my baby nephew. A large basketwork garden armchair

was my contribution to the jumble of baskets, tables and

chairs which cluttered the decks of Melita when we steamed

homewards. Lisbon was our final land call when we managed a

visit to Estoril and enjoyed a swim in the Atlantic as it

rolled on to the sandy beach.

These `Mediterranean cruises' of the thirties were surely

the beginnings of foreign travel holidays which play such a

significant part in the life of most people nowadays.

For

Peace comes Dropping Slow.

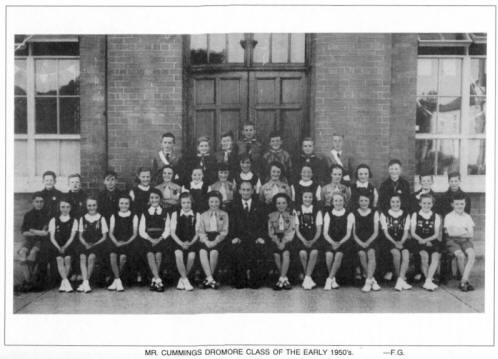

G. HARRIS CUMMINGS, TEACHER, 1922-1981

By Roy Gamble.

You burrow deep in the recesses of the mind, turning it

out like an old pocket; fingering the debris of forty-odd

years; searching for th e

elusive glitter of golden memories. And they come only in

fits and starts, a faded flickering news-reel: shadowy

figures; days and dates; half-remembered words. e

elusive glitter of golden memories. And they come only in

fits and starts, a faded flickering news-reel: shadowy

figures; days and dates; half-remembered words.

But the essential element remains: the central character,

clear and bright and tangible; frozen in time like the

powerful outlines of an old-fashioned Daguerreotype

photograph.

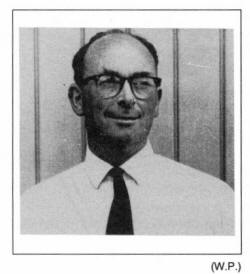

He wasn't a big man in the physical sense, but he strode

into the classroom and our lives like a pocket Colossus.

It was the way he carried himself and that dapper sense

of dress that you noticed first, And then there was the

receding hair, the kind eyes, the sympathetic smile.

He was one of those men who was always spotlessly clean

like a surgeon or old-fashioned family doctor. He had about

him an aura of well-scrubbed good health: the apple-red

cheeks, the strong black-haired arms and hands.

On that first day he demonstrated his abhorrence of

corporal punishment with a single dramatic act of dismissal

when he flung the cane, that waspish instrument, down the

back of a tall cupboard that stood at the back of the room.

It was never seen again.

This was G. Harris Cummings: teacher, mentor, enlightened

and compassionate human being; demonstrating, as he was to

demonstrate all his too short life, that actions speak

louder than words.

It was late August, 1949 when he came to us, we fortunate

few who were to benefit from his teaching and his wise and

benevolent presence for the next few memorable years.

His journey to Dromore was circuitous - a five year war

interlude had seen to that. In 1940, with the world already

one year into war,

a youthful Harris Cummings left his father's farm at Woodend,

Londonderry road, Strabane ` and boarded the train for

Belfast. Armed with

his newly acquired Senior certificate he was on his way to

enrol for teacher training. On the journey he shared a

compartment with two

Strabane boys en route to join the Royal Air Force.

No-one will ever know what conversation took place in

that railway carriage. But the rest, as they say, is

history.

He served out his war as an aircraft engine mechanic,

hands permanently grimed with grease and oil as he grappled

with the innards of giant engines, tediously servicing the

heavy bombers that raided nightly into Germany from R.A.F.

Colerne, Wiltshire. M.P.)

Not for him the kudos and glamour of flying duties - but

typical of the man, he accepted his place in the military

scheme of things, served without demur, and later wore his

medals with pride.

He brought to teaching a strength of character forged in

the awful ordeal of conflict, experiencing first-hand the

horror and waste of war. Ground crews, responsible for

servicing operational bombers lived like troglodytes:

sleeping on make-shift beds in dingy airfield crew-rooms;

seeing off the heavily-laden bombers at dusk, waiting as

first light bruised the night sky for them to return, often

shot-up, half their crews (pilots, navigators, wireless

operators, gunners - men Harris Cummings often knew

personally) dead or badly wounded. Or worse still, enduring

the incomprehensible finality of the sudden termination of

the young lives of those who failed to return - shot down

over Dusseldorf, Cologne, Bremen.

There were good times too. Despite the war-time

restrictions on travel there was a chance to see something

of the England he grew to love, and along the way, the

God-sent opportunity to meet, court and wed the charming

Miss Malveen Jones from Bath, Somerset.

Had there been an R.A.F. station at Coleraine, Co. Derry

this last happy event might never have happened, thanks to

the bungling of a movements clerk in some R.A.F. orderly

room. The unfortunate clerk, failing to distinguish between

Coleraine Northern Ireland and Colerne, Wiltshire,

dispatched Aircraftsman Cummings back to Ulster for what was

to prove a very short-lived first posting.

The raising of the school-leaving age in April, 1947

prompted the Teachers Emergency training scheme, and Harris

Cummings became one of the many ex-servicemen to train in

the Emergency teacher college at Larkfield near Belfast.

In "Goodbye Mr. Chips" James Hilton's pre-war novel about

school-mastering, Mr. Chipping's young wife Katherine goes

some little way in summing up Harris Cumming's proud

profession when she addresses her husband: " ` Oh Chips, I'm

so glad you are what you are. I was afraid you were a

solicitor or a dentist or a man with a big cotton business

in Manchester. Schoolmastering is so different, so

important, don't you think ? To be influencing those who are

going to grow up and matter in the world . . .'

Chips

said he hadn't thought of it like that - or at least, not

often. He did his best; that was all anyone could do in any

job. Chips

said he hadn't thought of it like that - or at least, not

often. He did his best; that was all anyone could do in any

job.

No-one could accuse Harris Cummings of not doing his

best. It was not in his nature to do otherwise. He obviously

thought long and hard and often about his job. As a teacher

he was twenty years ahead of the times. Fingers numb from

caning; the wooden duster flung in anger; the repetitive

rap, rap, rap of the pointer beating out the sing-song

rhythm of times tables played no part in his teaching

methods.

He carried his authority easily, teaching by example.

Never content with merely passing on the fundamentals of the

three R's he opened and expanded young intellects with

wellweighed words and patient encouragement.

An avid exponent of the old adage: "All work and no play

makes Jack and Jill a dull boy and girl" - he was just as

likely to shout, in the middle of a particularly tedious

lesson:

"Right, close your books," and splitting the class into

teams, begin an energetic refereeing of a no-holds-barred

general knowledge quiz.

Impromptu classroom concerts were also a periodic pleasure

when he would act the yokel and sing, whistle and grunt his

way through:

"There was an old farmer who had an old sow, (Wheep,

grunt, deedily-dan)

Who took her to market some goods for to buy, (Wheep,

grunt, deedily-dan),

Sing Lassie go-ring go-ro Susannah's a funniful man (Wheep,

grunt, deedily-dan.)"

"Do the Welsh railway station," we would shout, and he

would oblige, rolling his tongue round that elongated

jawbreaker of a place-name on some remote Anglesey

branch-line, syllabically correct and complete with

appropriate accent: LLanfair-pwill-gwyn-gyll-goger

ychwyrn-drobwll-llanty-siliogogogoch. Which means, as he was

always at pains to point out: the church of St. Mary's by

the white hazels over the whirlpool close by the church of

St. Trisilias by the red cave!

These polished performances came as no surprise for he

had already appeared on the stage proper, treading the

boards in two of Dromore Cathedral dramatic society's

productions in 1950. "In a Glass darkly" a one act play by

Muriel Box, he starred in the role of love-lorn portrait

painter Robert Keene. Later he was cast as the 'boy-friend'

in a three-act comedy called "The Younger generation" by

Stanley Houghton.

Harris Cummings was a child of the Empire. Born at a time

when at least a third of the globe was shaded a bright

Britannic pink, he made no apology for being a Royalist and

a supporter of the Union. This is not to say that he

possessed a "Little Englander, the sun never sets on our

dominions" mentality, for he was much too thoughtful and too

much an Ulsterman for that. Nevertheless, he was still an

ardent admirer of British achievements and he was happy to

be part of local celebrations for the Festival of Britain in

1951 and again in 1953 when Queen Elizabeth the second was

crowned.

His love of things English was always evident as he

coloured lessons with mental pictures of the villages and

shires and traditions of England. A lifelong lover of sport,

he introduced us to cricket - that most quintessential of

English pastimes and to the voice of that fine radio

commentator, John Arlott, often breaking into a highly

passable impression of that marvellous Hampshire burr: "And

Trueman comes in to bowl as the pigeons `roise' at the

pavilion end . . . "

I think it was John McGahern the writer who said "There

are no days more full in childhood than those days lost in a

favourite book." Harris Cummings, normally an advocate of

action, recognized this, and despite the busy grammar school

qualifying curriculum, encouraged our first exciting

insights into those imaginative books: `Treasure Island'

"Kidnapped' `The Wind in the Willows' `The Kon-Tiki

Expedition.'

He was moved by curiosity and it rubbed off on those

taught. He had this capacity to transport his pupils to

far-flung places: Africa, India, China. It was not so much

the basic factual knowledge ( though there was that too )

rather the sense of adventure he engendered so that we

barely noticed the facts and figures and dates along the

way.

It is strange that he, most practical of men, should have

been the one to stir that first small flame of poetry,

putting an end forever to the `Half a league half a league

half a league onward' breathless chanting. "Emphasis the

`Peace comes dropping slow,'" he would enjoin and proceed to

recite in drawling demonstration those lovely lines from W.B.

Yeats' "The Lake isle of Innisfree."

"And I shall have some

peace there,

For peace comes dropping

slow,

Dropping from the veils of

the morning

To where the cricket sings;

There midnight's all a

glimmer,

And noon a purple glow,

And evening full of the

linnet's wings."

The era following the ending of the second world war was

a particularly drab time in the United Kingdom. Austerity,

utility and rationing all continued into the early fifties.

Only a tiny percentage of the population owned cars, and for

most Dromore children, a once a year steam train Sunday

school excursion to Newcastle was all that expected in the

way of travel. Some of us had not yet been to Belfast in

1950. Harris Cummings changed all that. With almost military

precision ( right down to the exact amount of money required

for trolley-bus fares ) he organised several highly

educational trips to the capital. Small beer now-a-days

perhaps compared to school trips to London, Paris and Rome;

we nevertheless enjoyed our visit to parliament buildings at

Stormont, where, never one to miss an opportunity to impart

knowledge, he delivered an off-the cuff geography lesson

over a fine bronze relief map of Ireland laid out in the

imposing foyer of the parliamentary pile.

Later there were visits to the Ulster museum, the Zoo,

and the Victorian grandeur of the palm house in the Botanic

gardens. And of course, there was the piece-de-resistance of

each and every trip - lunch in the massive Woolworth's

cafeteria in High street. The height of culinary

sophistication !

I was twice blest in my relationship with Harris

Cummings, for not only was he my revered schoolteacher, he

was my leader in the 3rd Dromore Life Boy team (the junior

section of the Boy's Brigade) an organization he loved and

led with pride.

Trips to Belfast continued as he organised highly

competitive football matches and other get-togethers with

City Life-Boy teams.

Someone once described a religious person as, "One who

believes that life, and its aftermath, is about making some

kind of spiritual journey." Harris Cummings was one such

person. A deeply Team Manager, 3rd Dromore Life Boy Team -(W.P.)

religious man, I can still picture him leading our

adolescent voices in singing the vesper hymn at the close of

another Monday Life Boy meeting. Hushed singing, after an

evening of disciplined activities and boisterous boyish fun,

the late Summer sun shafting through the high windows of the

church hall:

"The day thou gavest,

Lord is ended,

The darkness falls at thy

behest;

To thee our morning hymn

ascended,

Thy praise shall sanctify

our rest."

A short time after I left Dromore primary school, Harris

Cummings took up an appointment as Principal of the new

school in Loughbrickland. It might as well have been on the

other side of the world. Now and then, as is the way of

things, news of him would filter through: his successes with

11 plus candidates; his M.B.E. for outstanding service to

the Ulster savings committee; Presbyterian church

activities; Presidency of the Royal British Legion; his

formation of the first Loughbrickland Boys Brigade company.

All news was good news.

I only ever saw him one more time; sometime in the middle

seventies. It was in a crowded Banbridge street thronged

with Saturday shoppers. He had put on a little weight; grown

a little smaller. I didn't have the temerity to stop and

introduce myself, but shyly said hello and passed on. The

gap of our acquaintanceship was too wide, and besides, he

was still, as he always will be, Master Cummings, my

extraordinary and highly-respected teacher.

He died in January, 1981 having suffered from that most

cruel of illnesses, pancreatic cancer. To the end he was

courageous. " Are you in pain ?' they would ask. " It's only

a niggle, " he would reply. " Only a niggle. "

To this day I bitterly regret never having gone to see

him. To thank him for his good influence on my life, for

happy Life-Boy memories and for the shining example he gave

to all who sat at his feet in his classroom.

He always sought the best in people, refusing to belittle

anyone; rather seeking the hidden good.

"And still they gazed, and

still the wonder grew,

That one small head could carry

all he knew.

But past is all his fame. The

very spot

Where many a time he triumphed,

is forgot."

Let these few lines from Oliver Goldsmith's

"The Village Schoolmaster" be a fitting epitaph - with the

exception perhaps, of the final couplet. For no-one, least

of all this ageing former pupil, could easily let go the

memory of the phenomenon who was G. Harris Cummings.

|