The 18th Century saw the early development of the linen

industry which was to become Ulster's and Dromore's major

industry for the next 200 years. The physical conditions in

Ulster provided an ideal environment for the linen industry.

Linen was woven from fibres of flax and the mild, moist

climate of Ulster allowed for the growth of a long fibrous

stem essential for the finest yarn. But these physical

advantages had to be exploited and the first step was taken

when William III invited Louis Crommelin to settle in the

Lisburn area in 1698. Crommelin was appointed "Overseer of

the Royal Linen Manufactory of Ireland".

Crommelin's work was laid on sound foundations. The Irish

textile industry had a tradition stemming back to the 15th

and 16th Centuries for the production of fine yarns. Also in

the 15th and 16th Centuries there had been a steady

migration from the North of England into the Lagan Valley

area of people who had an indepth knowledge of textiles. The

consequences were that handloom weaving and bleaching was

well practised by the time Crommelin arrived.

The Lagan Valley also provided a favourable position due

to its swift tributaries enabling water powered machines to

be used for the finishing of cloth. The Lagan also aided

communications by allowing bleachers to collect unbleached

cloth from all over the north.

The linen industry at this early stage would have had

little effect on Dromore's townscape. This was because the

linen industry was still a cottage industry and not factory

based. Linen was fully integrated into the agricultural

system as a method of supplementing agricultural earnings.

All members of the family were involved, with the land

providing the subsistence existence supplying oats,

potatoes, flax and milk. After the linen had been woven and

spun on the farm, the unbleached linen was brought to the

Brown Linen Markets where drapers bought it. These were the

middlemen linking the producer to the merchant. The draper

bought the linen, bleached and finished it then he had to

carry it to be sold in Dublin which was the only major

commercial centre in Ireland; this exemplifies the still

primitive nature of the Irish urban system.

Although the nature of the linen industry in the 18th

Century was that of a cottage based industry in a rural

setting it did have some effects on the development of

towns. The morphology of Dromore remained largely unchanged

as the linen industry was still a branch of agriculture and

did not locate in the town.

However the linen industry reaffirmed the role of many a

town as that of a market centre. Fine brown linen halls were

built in Lurgan and Belfast. (They were termed Brown Linen

Halls as the linen was sold unbleached). A more modest

Georgian linen market hall was built in Dromore in 1752.,

E.R.R. Green claims that considerable quantities of linen

were sold in Dromore, however, it was too near the great

Banbridge linen market to develop. This indicates that

Dromore's later role as a secondary linen town compared to

larger nearby centres such as Lisburn and Banbridge had

already been established.

Dromore's primary function in the late 18th and early

19th century was as a market centre for linen and

agriculture. Dromore had the only flax market in the Lagan

Valley. Meal and potatoes were sold in the market house,

with meat sold in the adjoining shambles. The market was

held every Saturday, plus five fairs were held annually

selling cattle, sheep, horses and pigs. Dromore was to act

as the market centre for the middle tract of the Lagan

Valley and a greater part of the mountain tract. Dromore's

role was typical of most inland Irish towns.

Dromore also experienced this expansion in the bleaching

industry because of its position on the River Lagan. The

only evidence that I found of the existence of numerous

bleachworks in Dromore in the early 19th Century came

through retrospective comments. The Lewis's Topographical

Dictionary of Ireland in 1837 commented that there were

formerly several bleach greens at work in the vicinity of

Dromore, but now there was only one. This comment was echoed

by a Dromore Presbyterian minister who in 1836 said:

"We had formerly 6 bleachmills and greens, now only 1".

The one bleach green which still existed probably

belonged to the firm of Messrs. Thomas McMurray & Co., who

established a bleachworks at Quilly to the south of Dromore

in 1827.

These comments also indicate the decline in the number of

bleachmills which occurred in Dromore and the rest of

Ulster. By 1850 there were only 90 bleach mills left in

Ulster but they were, on average, much larger than those

which had operated in the earlier years. The decline in the

number of bleach mills started from about 1800 due to

growing competition from the cotton industry in Ireland and

England. Another reason is that the highly capitalist nature

of the linen industry meant that only the most efficient

survived and consequently many of the smaller bleachmills

became uncompetitive - this would also account for the

increase in the average size of bleachmills.

The decline in the power and number of bleach mills was

compensated in Dromore by the location of other branches of

the linen industry in the town. The cambric industry (which

is a finer quality of linen) concentrated itself in Lurgan,

Dromore and Waringstown. Thomas Scott moved his premises to

Dromore in 1817 and became regarded as one of the principle

manufacturers of cambric in Ireland. This was a high value

product with it's selling price reaching as much as 1 guinea

per yard and it's processing requiring skilled labour.

Thomas McMurray would also boost the linen industry in

Dromore by adding linen weaving to his bleach works soon

after his arrival in 1827.

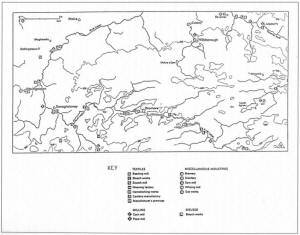

Map 3.6 also indicated how the location of many of the

processes were related to the river, with almost all the

industry concentrated on the banks of the Lagan, showing

that water was the still the power behind the linen

industry.

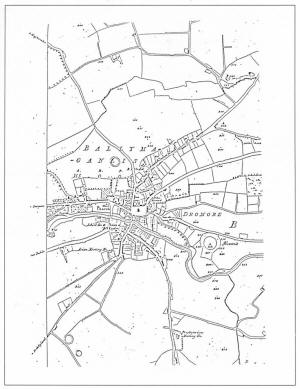

By the 1830's Dromore had experienced a growth of the

linen industry in the area surrounding the town. Map 3.7 is

an Ordnance Survey map of Dromore in 1833 and although the

street plan has remained relatively unchanged since the 18th

century, there has been some tangible evidence of the growth

of the linen industry. There was development of houses along

Meeting Street and Mount Street, which were constructed in

the early 19th Century as homes for textile workers. These

houses were typical of much of the housing development built

for linen workers being modest two-storey houses, "built

with the hill". The only other major change to the street

plan was with the construction of Prince's Street leaving

the north-east of the square on the road to Hillsborough.

The weaving and spinning industries were still relatively

primitive and had yet to experience the industrial

revolution. Consequently Dromore like the rest of Ireland

was still a rural, agricultural society. With the exception

of the dramatic growth of Belfast, the urban populations in

Ulster had remained small. The conditions had not yet been

created for the rapid expansion of the linen industry, and

Dromore's main function remained that of a market centre.

The Dromore and District Historical Group wish to thank

all the Primary School children who so ably supported the

Civic Week story writing Competition. The Winners in each

age Group were as follows;

The theme of emigrating from Dromore during the last

century provoked a wide range of response from local

children.

We were regaled with stories about the ghastly journeys

across the Atlantic in which so many perished. Incarceration

at Groose Island was also mentioned as were encounters with

the native Indians.

Among the reasons mentioned for leaving Dromore the

potato blight and subsequent famine came high on the list,

but the search for work and in one case for a husband! were

also given priority.

Feelings of homesickness were, for the most part,

outweighed by the relief and happiness at the security found

in the New World. Offers of help and money were sent home

and promises made of coming back for a holiday - sadly there

was no story of a triumphal return.

|

|

|

Key |

|

TEXTILES

KEY

B Beetling min

L Bleach works

S Scutch mill

W Weaving factory

H Hemstitching works

A Cambric manufactory

M Manufacturer's Premises

MILLING

C Corn mill

F Flour mill |

MISCELLANEOUS INDUSTRIES

B Brewery

D Distillery

S Saw mill

H Whiting mill

G Gas works

DISUSED

L Bleach works

|

|

`THE WAR

YEARS'

By Jim McAlister

I joined the firm of John Graham (Dromore Ltd.), Building

and Engineering Contractors, Lagan Mills Dromore Co. Down on

the 21st March 1938 and completed my apprenticeship of five

years and remained until the 11th of September 1945. Whilst

serving my apprenticeship

I was sent to Banbridge Miles Aircraft Ltd. where I was

engaged for some time on the construction of Mosquito Timber

Framed Fighter Aircraft, and subsequently to Stormont to a

course in Steel Bridge Construction to the best of my

knowledge under the direction of Army personnel. The reason

was that people trained in this particular field of design

and construction would be on standby if required during an

emergency to take charge of and supervise the erection of a

new temporary steel replacement structure. In addition

whilst serving my apprenticeship I was responsible for the

design of the artistic work which was displayed on the gable

side of Dromore Town Hall for:

(1) Salute the Soldier Week

(2) Salute the Airforce Week

(3) Salute the Navy Week

My father was mainly responsible for the latter and I

helped him with the construction of a detailed model of the

`Ark Royal' which was taken around the streets of Dromore to

raise money for the Navy. Eventually I was informed that the

Royal Naval Cadets at that time were presented with the

model. I often wonder if it is still in existence.

I would also point out that my father was one of the

founders regarding the name "Dromore United" and assisted in

choosing their colours, amber and black, in which I think

they still play. He was also a flautist in the Bruce

Hamilton Band. My father was a Master Craftsman and was in

partnership with Mark Gardiner, my uncle, i.e. Gardiner and

McAlister Building Contractors, located adjacent to Dromore

P.E.S. (now the Church of Ireland Parochial Hall). The site

is now owned by Mr. Bertie Tinsley, car dealer. I think it

was called Sheiling Hill.

The above firm carried out much work in Dromore and

district e.g. Church work, schools and houses etc. Banbridge

Road Church and Magherabeg School house, to the best of my

knowledge, were built by them.

Eventually the partnership discontinued and my father

joined up with John Graham Ltd. and remained there until

retirement. My uncle was appointed Clerk of Works in charge

of the Banbridge Road School being built at that time. Now

the present Dromore Central Primary School.

I would also like to tell you about my brother in law Jim

Gracey, who left Dromore in October 1947 to go to

California. A farewell party was held in Dromore Orange

Hall. I was approached and asked to provide music on the

piano accordian . At that time I had no idea that Jim would

be my future brother in law. When Jim left Dromore it was

said jokingly that he may end up on the films and by

coincidence this did happen. Jim was attending an Irish

Dance and was picked to take part in the film "Luck Of The

Irish" starring Tyrone Power and Ann Baxter. He took an

active part in an Irish Dance scene. The news of this, when

the film came to Dromore resulted in a sell out at the local

cinema in the Town Hall.

Jim also held a responsible job with Lockheed Missiles

and Space Co. in the capacity of supervisor in Quality

Engineering.

He was promoted to the rank of Staff Sergeant in the

American Army in 1948. He saw service in Germany and three

years in Tokyo, Japan.

--Jim McAlister formerly of Gallows

Street, Dromore

GRANDAD'S

ARMY

By Sam Johnston

I had intended to someday write my own memoirs about my

time in the Home Guard in the early 1940's. Being retired

one has ample time for such an exercise, but procrastination

being my constant companion I kept putting it off to later.

However, Jim and Alison of the Dromore Historical Group

pressurised me constantly to produce it in time for this

year's Journal, and what with the 50th Anniversary of

`D'-Day being celebrated in Europe, I realised with a mild

shock that I had been demobbed over half-a-century ago and

time was no longer on my side; that I could be heading soon

for senility, and what had been cynically called "Dad's

Army" was now "Grandad's Army". So I'll rummage through my

creaking cranium and try to stir up some thoughts of those

stirring times.

After Germany had invaded Poland in 1939 there were

months of inactivity which were dubbed the "Phoney War".

Hitler put an end to that, and was now playing-for-keeps in

1940 when his armies over-ran Europe and was mounting an

imminent invasion on Britain itself. It was the time for all

good men to come to the aid of their country and the Local

Defence Volunteers (L.D.V.) was formed from the civilian

population. They were later called the Home Guard, or

mockingly, Dad's Army. The late George Formby who was in his

prime then singing silly songs on his Ukulele, poked fun at

us by singing a number called, "I'm guarding the home of the

Home Guard". One verse went something like this:

I'm guarding the home of the Home Guard,

I'm guarding the Home Guard home.

All night long steady and strong,

Doing what I'm told and I can't go wrong.

Now one night as an L.D.V.,

Four big Germans I chanced to see,

They ran like the wind but they couldn't catch

me,

When guarding the Home Guard home.

Being only sixteen years old I was two years short of the

enlisting age, but on the assumption that I could pull a

trigger or stop a bullet in spite of being on the young

side, I was admitted to the ranks. We were an amalgamation

of Dromore, Dromara, and Waringsford and were officially

known as "D" Company, 4th Down Battalion. Major William

Copeland was our commanding officer and tailor-made for the

job as he had done some soldiering in his early days, and

knew what army life was all about. When he marched at the

head of his column of men on parade he was every inch a

soldier and he had our respect.

Our drill hall was a disused stitching factory in Meeting

Street, the entrance was opposite Mr. John McGrehan's shop

and known as Scott's Entry, and was situated where the

houses in Brewery Lane now stand. It was quite roomy and

ideal for the job and it was here we learned the rudiments

of war.

We were issued with rifles and had to remember the number

stamped on a little boss on the end of the barrel. It is

also stamped in my memory to this day - G7621. We had

rifle-drill and inspection, for after a day on the rifle

range the sooty deposits left behind in the barrel had to be

washed out with a kettle of boiling water, followed by a

lightly oiled piece of cotton cloth pulled through the bore.

It was truly a "boring" exercise and inclined to be

neglected by the lazy element amongst us. It was a common

sight to see three rifles standing like a tripod when not in

use. This is achieved by interlocking a little metal "cleek"

near the end of the barrel called a piling swivel. One

private when asked by his C. O. to describe it's function

said in confusion that it was a "swiling pivel" and if you

had any swiling to do, this was what you pivelled it with!"

When our instructor was explaining the various rifle parts

he made particular mention of the smallest part with the

longest name. It was to be found at the base of the

calibrated rear sight and measured a mere 3/8 of an inch and

was called "The radial-arm axis washer retaining pin". Which

you will agree, was a rather grandiose name for such an

insignificant component. I made a conscious effort to

remember this information, but looking back I can't claim

that this knowledge played any significant part in the

defeat of Germany!

We were also issued a cloth bandolier of 25 bullets and

were under strict orders to remove and conceal the rifle

bolt which would render the rifle useless should it be

stolen. I had not as yet fired the gun and was very wary of

the live ammunition, but before I put them away that first

night in my bedroom, I was foolishly brave enough to

experiment and loaded a clip of five bullets into the

magazine. Getting them out again entailed working the bolt

in and out five times to eject them - and I took cold feet.

I was certain that I would do something wrong and blow a

hole in the ceiling, or worse! To be on the safe side I

opened the window and pointed the muzzle - along with my

prayers - heavenward, and with hammering heart, heard the

bullets come clattering out to the accompaniment of my

chattering teeth. This war was a serious business!

Then there was the bayonet which hung from a scabbard

slung from our belt. It was a sinister looking piece of

cutlery and when mounted on the end of the rifle we would

practice lunging at an imaginary enemy, aiming for the

throat or the groin, though in the heat of the battle any

part of the enemy anatomy would have done! Major Copeland

possessed a noted dry wit which came to the fore when he

once lectured to a squad of men on the do's-and-don'ts of

bayonet fighting. "Don't", he said, "penetrate your enemy by

more than three inches, more than this is extravagant and

time-consuming." (I was tempted to ask how one measured

three inches in the heat of the battle.) "Do remember to

withdraw your bayonet from your adversary's body as he gets

very hard to carry on the end of your rifle after a few

hundred yards! Don't fling him over your shoulder like a

sheaf of corn as you are liable to blind your buddies

charging in the rear!" Fortunately, we never had to put

these tactics into practice. Rumour had it that one private

in Dromara had mastered the act of swallowing his bayonet

after seeing sword-swallowing performed at a circus. He said

the trick was, he swallowed the scabbard first which

prevented the bayonet from nicking his neck!.

If the bayonet was a rudimentary killing weapon, the

Spigot Mortar was anything but. It consisted of four heavy

metal tubular legs that fitted horizontally into a

base-plate which anchored the whole assembly to the ground.

The barrel and firing mechanism pivoted on the base-plate

and was manned by four men. It fired anti-tank and

anti-personnel missiles weighing up to sixteen pounds, and

it was a brute to assemble. The only safe place to fire this

ungainly killer was up at Slieve Croob, to where it was

transported in an obliging grocer's lorry! There, under the

scrutiny of a Regular Army Major - an Englishman - we fired

at large rock formations posing as tanks at around 300 yards

range. Our squad were allowed one shot each and our first

two anti-tank bombs were an anti-climax as they landed in

boggy ground and failed to detonate. But I can still feel

the exultation when my shot was "dead on" and exploded in a

cloud of black smoke and a frightening detonation which

reverberated around the hills. When we packed up and left,

the Major remained to locate and blow up the unexploded

missiles, and we didn't envy his task!

The annals of warfare are stippled with accounts of

mountain confrontation such as The Battle of Bunker's Hill,

The Battle of Vimy Ridge, and The Battle of Monte Casino,

and I would add to that list The Battle of Slieve Croob, in

which the Home Guard played an insignificant part!

We had just unloaded the cumbersome Spigot Mortar and

were about to commence firing when the enemy appeared over

the brow of the hill in the person of an old sheep farmer

who lived in a little stone built house nearby. He informed

the English Major that there would be no more firing of

weapons as they were disturbing his sheep which would soon

be lambing. The Major, with an imperious wave of his arm,

brushed the old man's protestations aside and gave him a

short lecture on the more pressing importance of winning the

war compared with coddling pregnant sheep. The old fellow

said no more but produced a letter marked O.H.M.S. and

handed it to the Major. It was from the Ministry of

Agriculture, and addressed to whom it may concern, and

stated that in the interest of food production, no weapons

or manoeuvres of any kind were to be discharged during

lambing season. The Major fumed and flustered. If needs be

he was prepared to go down fighting against the Hun! But to

capitulate to a lone shepherd flaunting a piece of paper was

as debasing as being demoted from Major to private! As for

the rest of us, semi-hardened soldiers that we were, we had

been beaten by a lone farmer, a peasant, and we retired like

gentlemen. You will notice that I use the word `RETIRED'

rather than `RETREATED', for the latter word smacked of a

disorderly rout and was not in our Home Guard vocabulary!

We had our rifle range in a field called Wallace's

Meadow, a tract of land that ran from Maypole Bridge to Holm

Terrace. It was ideal for the purpose for the targets were

placed at the foot of the very high railway embankment which

smothered stray bullets. A small stream bisected the field

and was easily forded as it contained little water. But once

after a thunderstorm and cloudburst it became a raging

torrent. We arrived for shooting practice in full combat

gear and rather than make a long detour to reach our firing

point, the younger element found that with a fast run we

were able to jump across. Our most elderly private, Old

Jimmy, was game to have a go, and with his helmet on his

head, his rifle in his hand, and his gasmask slung across

his chest, he came galloping down and took off from the

bank, and might have made it had not his gasmask, which

should have been secured by its string, bounced up and hit

him full in the face. He fell like a shot snipe into

mid-stream and waded out shaking himself like a water

spaniel! Apart from his pride nothing else was hurt and he

was taken home in a "field ambulance" in the guise of a

grocer's lorry! Nothing daunted, he changed into his civvies

and returned to finish the course.

I cannot speak of Wallace's Meadow without recalling a

near fatal accident that happened there during rifle

practice. The exercise was on orders to stand and load the

rifle, place a live round up-the-spout, apply the

safety-catch, crawl ten yards, and fire at will. The first

squad to go was composed of `B' Specials who were inducted

into the Home Guard and were receiving orders from their

Second Lieutenant. He stood in front of them and gave the

order, "Standing Load", which they did, only for one man to

absentmindedly pull the trigger. The unexpected crack of the

rifle and the whoosh of the bullet over the officer's head

stunned every man there! When the officer realised he was

still alive he fired a volley of colourful expletives at the

errant rifleman. When he had run out of oaths and breath

Major Copeland refreshed his memory and berated him with a

few more livid ones, for, as he said, "Only a blankedly

blank fool would give orders standing in front of men

handling live ammunition". It was sheer comedy for the rest

of us standing around. Comedy sharpened by the relief that

nobody was killed!

Shortly after that I did lose a good friend - my rifle.

It was taken from me when they issued me with another weapon

called a Grenade Cup Discharger. I was loath to part with

G762I for when I had cleaned and polished it, carried it on

parades and manoeuvres, and seldom let it out of my sight,

it was almost a part of me, and there was a certain dismay

when another rifle took it's place. The fact that only a few

Cup Dischargers were issued helped to soften my regret, for

they were a much envied weapon. They were modified rifles,

having the barrels bound with whipcord to prevent them

splitting when the grenade was ejected from the metal cup

affixed to the barrel, by a cartridge of compressed gas. So

severe was the recoil, they could not be fired from the

shoulder. Instead, the butt was placed on the ground and

rifle held at an angle around 45 degrees by the kneeling

marksman, to avoid damage to the forefinger it was whipped

smartly out as it pulled the trigger. The exercise once led

to a Guardsman jerking his rifle from it's 45 degree

position to the perpendicular, sending the grenade

vertically overhead. Someone shouted the four-letter word,

requisite for such occasions, "DUCK", and we all shrank as

small as possible beneath our steel helmets, mingling oaths

and prayers which were answered when the grenade exploded

harmlessly away above our heads. It had been a close

encounter!

One Sunday afternoon we were alerted to muster at the

Drill Hall! An emergency had arisen when some German

prisoners-of-war had escaped from a camp at Scarva. Our

orders were to search Gillhall demesne which, with all it's

bushes and undergrowth, afforded a likely hiding place for

escaping prisoners.

We approached from the Quilly Road direction and having

spread out, we advanced towards likely cover. Even now I can

feel how vulnerable we were had there been a do-ordie armed

German waiting to pick us off as we neared his hiding place!

It heightened my perception of the bravery of our soldiers

who advanced up the beaches of Normandy on DDay. In the

event we scoured Gillhall, and put it all down to

experience. We took no prisoners!

During the annual weeks holiday off work in July our

Battalion was taken to army camps for more intensive

training. The three bases we attended were at Ballykinlar,

Narrowwater Castle where American G.I.s had just left to be

deployed in England in readiness for the D-Day invasion, and

Ballycastle, our billets there being requisitioned guest

houses. A number of ladies from Dromore and Banbridge

districts who were members of the Women's Voluntary Services

(W.V.S.) under the direction of a Regular Army Sergeant

Cook, saw to all culinary needs, and if an army marches on

it's stomach our Battalion didn't lack mileage!

When we were based at Warrenpoint, and the Irish Free

State, as it was then called, had taken a neutral stance,

and as Omeath lay just across Carlingford Lough it was out

of bounds for British soldiers, so our fellows brought their

civilian clothes with them, and dressed in these, they made

evening sorties in the ferries that plied between both

towns. Their objectives were to invade the pubs in Omeath

and consume the cheap liquor which was in plentiful supply.

Fortunately, none were interned or shot as spies for they

all returned safely if not soberly! One night four such

gentlemen returned home to their billet, which I shared with

them, as "tight-as-drums", and as they prepared for bed they

decided to have a cursing match! I was once told by a

clergyman that there are basically about four such oaths

(and who am I to question that?) and our four heroes were

frustrated when they couldn't think of any more, and soon

fell into a drunken stupor. My abiding memory of that

inglorious night was of one of them partially undressed, on

his knees, bent forward with his forehead resting on his

pillow, snoring away in this suppliant posture!

When attending these camps we had to do our stint of

guard duties, operating out of the guardhouse on a 2 hours

on, 4 hours off rota throughout the night. One guard showed

his bravery by lying down in his sentry-box, wrapped up

snugly in his great-coat, and a small bottle of whiskey at

the ready to keep the elements out, if not the enemy at bay.

As far as he was concerned all was quiet on the western

front!

I have mentioned the great-coat. We were allowed to keep

it after we were demobbed, and many were pressed into

service as an extra blanket, there being no electric

blankets in those days. I knew of one such coat which was

still being used on the bed, especially on cold nights, long

after the war was over. Indeed it was not until he brought

his bride home that she delivered the ultimatum that either

it went or she went. But no way would the three of them

share the bed simultaneously. So the coat was pensioned off-

it being well past the pension age anyway - and a new

bedspread was purchased in Lisburn market the following

Tuesday. The stall-holder assured them that he had sold

hundreds of such bedspreads throughout Ireland and they

covered a multitude of sins!

It was an Army Order that under no circumstances was a

soldier to surrender his rifle to anyone - not even the King

- when on guard duty. To test one man's understanding of

this a C.O. doing his rounds of the camp asked a guard what

his duties were, and he said he was guarding the riflehut.

He was then requested to hand over his rifle for inspection.

On so doing his C.O. pulled the trigger and blew the man's

cap off and then berated him for being so foolish in

relinquishing the gun. The trembling soldier retrieved his

cap with the bullet hole in it, and the C.O., relenting,

gave him a few shillings, saying it was for the damage to

his cap. "Thank you very much sir", said the soldier, "and

what about the damage to my trousers?"

Another mishap allegedly happened to a platoon of Home

Guards who were on a night manoeuvre which entailed them

advancing across a field in complete darkness, in what was

known as "pepper pot formation". One man suddenly remembered

seeing a large bull in the field that morning, and told the

Major that the bull was dangerous. He promptly blew the

recall whistle and everyone retired to the roadside, where a

quick roll call revealed one man missing. The Major gave

another blast on the whistle, and immediately there was a

commotion away across the field. Eventually Old Jimmy

appeared out of the night, very dishevelled and bedraggled.

On being asked what delayed him, he explained he had been

knocked down by a cyclist in the darkness, but he had

managed to get to his feet and had a firm grip of the

handlebars, and only he had heard the whistle, he would have

taken the bicycle off him!

About once a year we went to Ballykinlar Army Base for

shooting competitions, where the "Dead Eye Dicks" from the

various companies competed for cups and trophies. Big

stories had been circulating about the prowess of some

marksmen. We put out a story that due to a faulty

rangefinder on his rifle, which was stuck at 100 yards range

our marksman was still able to hit the 200 yard bullseye

every time by bouncing the bullets off a boulder half-way

down range! We had one very consistent rifleman called Davy

and we were sure he would be amongst the prizes. Instead, he

had one of the lowest scores. It transpired he had borrowed

his pal's rifle which looked very new in comparison with his

own. It brought home to us the proverb, "Never change horses

in mid-stream".

However, all was not lost for in a Young Soldier's Plate

competition for teams of four junior marksmen, and of which

I was a very proud private, we beat all comers. We were

elated, but none more so than Major Copeland. He held the

Cup aloft as though it was the spoils of war. I still have

the photo that appeared in the local press of our winning

squad. Sadly I'm the only living member.

In December 1943 the Home Guard was "stood-down" in a

final parade in Banbridge. Hitler was on the retreat and his

intended invasion of Britain was like a bad dream that

evaporates with the morning.

I suppose you could say we were only playing at war in

the Home Guard because we never came to grips with the

enemy, but handling lethal weapons brought it home to us

what the Regular Army and other Forces were up against when

they battled, and finally flattened Germany.

When the yearly Remembrance Day Services take place on

the 11th November and Binyon's lines are spoken for the

Fallen, it is with the utmost and heartfelt sincerity that I

repeat, "We will remember them."