| 1. | In summer and in winter, In sunshine, rain or snow, I walked the road from Leverogue To school in fair Drumbo. Just a Master and a Teacher With several classes each. To read, to write and work out sums, Endeavoured us to teach. |

4. | When the air raids came to Belfast The classes rose in numbers As children came to Drumbo To escape from German bombers. Many, many things we learned, In those happy bygone days. Things we never would forget As we went our separate ways. |

| 2. | I remember Mr. Morrison. Headmaster of repute, Miss Maxwell was the Mistress, Precise and quite astute. She took the girls for needlework, To teach us how to knit, It took so long to knit my socks, I'm afraid they didn't fit! |

5. | Poetry learned long ago I can remember still. Songs and music from the past I can recall at will. From time to time I go back home To Drumbo on the hill, My schooldays now so far away, But very near me still. |

| 3. | Although everything was basic, Not up-to-date like now, The things we learned, we learned them well, And life was good somehow. There was no central heating, No low-flush inside `loo', Pot-bellied stove supplied the heat The long, cold winters through. |

6. | In memory I'm setting out Down Ballycairn Hill, Past Sam Hanna's farmyard, Walking with a will. To Drumbo Schoolhouse, past the Church I enter in once more, With friends and pals from long ago, And gently close the door. |

|

Aline Hanna (Matthews) 1987 |

|||

It gives me great pleasure to provide a brief foreword to what you, the reader, will discover, is an interesting and thoroughly researched account of the historical origins of Drumbo Primary School. Dr. Chris Reid, its author, has cast his research net widely and this particular example of the history of an individual school, which has had such a close connection with Drumbo as a community over the years, is firmly rooted in primary sources, notably the relevant source materials from the period of the `national schools' now held by the Public Record Office (Northern Ireland). Some of these documents are in fact reproduced to good effect. The book is also rich in evocative photographs of the teachers and pupils of yesteryear, thereby providing a valuable historical record of the Drumbo area, not to mention interesting evidence of the changes in clothing and fashion styles of both adults and children during the past century.

These faces, from a past now lost and gone forever, stare out at us, the readers, across the years, provoking the obvious question - whatever became of them all'? Were their lives happy and fulfilled or otherwise'? Some of the teachers look proud of their profession, as well they might be, in a part of the world where education has rightly been valued. I was naturally intrigued to discover a `Herbert McMinn' (no relation to my knowledge) amongst the members of the class of 1918! 1 also wondered whether the girls' cookery class of 1919 had the makings of some good Ulster soda bread in their mixing bowls.

The recent letter from President Bill Clinton to the pupils and the reference to the establishment of the school's own Internet web site bring us right up to the present and I was pleased to see the school's commitment to Education for Mutual Understanding, through its involvement in the cross-community contact scheme with Saint Patrick's Primary School, Castlewellan, given due recognition. The appointment of Mrs. Ruth Daly, as the first female Principal in 1997 is also an interesting example of how the role of women in the management of primary education has developed positively in recent years. Things have come a long way from the days of `The Master' and Me situation described by one national school pupil at the beginning-of the century: 'The master put fear into every scholar ... for he used his cane.'

I would want to wish both Drumbo Primary School and this book well. It is a fitting celebration of over two hundred years of educational endeavour in the Drumbo district. Drumbo is no longer `out in the sticks', and the postal address of its school does not accurately reflect its forward-looking approach to education.

Professor Richard McMinn Principal

Stranmillis University College, Belfast

November 1999

The Presbyterian Church in Ireland, not unlike her parent church in Scotland has, from its earliest beginnings, stressed the importance of education and of presenting "the divine image of education encircled by her three children, Knowledge, Power and Virtue."

Interest in education was, to a large extent, the result of the religious characteristics of the Presbyterians. The Reformation opened the Bible and invited the people to read it for themselves. Consequently, the Bible was introduced into the family and with it other books, such as the Longer and Shorter Catechisms, to complement it. Thus it was felt that children must, at least, be taught to read these. This was the primary reason for the establishment of schools, which parents themselves for many years, a to maintain It has always been a Presbyterian principle that the responsibility for education is primarily the concern of parents and, the development of this principle has led as we shall see, to much controversy between Church and State.

The narrative that follows has been written in the hope that those who attended Drumbo National School, latterly to become Drumbo Primary School, might realise in a deeper way how much they owe to the opportunities afforded them in this unassuming rural school, in the heart of Co. Down.

History has been defined as "a past of more than common interest". It is

hoped that this edition of the history of education in Drumbo will prove

such to all who may read it, and that it will fall into the hands of all

lovers of Drumbo at home and abroad.

| Drumbo, Co. Down |

Christopher I. Reid December, 1999 |

The story so far - - -

It is generally accepted that the notion of `popular education' came to Ireland with the advent of the Plantation during the early 1600s.

The two gentlemen who had responsibility for the Plantation

in this part of Co. Down, namely James Hamilton, subsequently Viscount

Claneboye, and Hugh Montgomery, later to be known as Sir Hugh Montgomery,

were themselves students in Glasgow, and as historians relate, were "not

unmindful of the cause of education." Viscount Claneboye, in his will dated

16th December, 1611 stated:

| . . . for such profits as shall be made of my two parts or parsonage I do appoint the schoolmasters to be maintained as now I have appointed them ... and five pounds a year to be given to every one of them, out of the said Parsonage tithes, besides such monies as they shall have from the scholars for their teaching . . . " |

A survey carried

out in 1618-19 by Pynnar, recorded that:

| " ... the people in quite a few of those districts planted by Scottish undertakers took a lively interest in education and included a school in their building programme." |

Whether or not education had a foothold in Drumbo in these early days it is impossible to say, but there is ample evidence to suggest that the colonization of this area brought with it popular schools fashioned on the Scottish model. These would have been private pay schools and would not have received any encouragement or support from the civil authorities.

In the 1630s, owing to the influence of the Bishops, the control of the Established Church became much more rigorous and the co-operation which had existed between it and Presbyterians all but disappeared. By 1636 all ministers had to declare openly their conformity to the Established Church and by 1639, on the imposition of the Black Oath, all ministers were asked to report on the Presbyterians in their parishes. This was not an encouraging time for education or its development, as even after the 1641 rebellion and during the Twelve Years War, the period was described as a time when "all learning and convenient means for teaching the young had ceased."

During the

mid-1640s an ordinance establishing Presbyterianism was ratified by

Parliament and during this period parish schools began to flourish again.

This development of education lasted until about 1661 when Charles II was

restored to the throne. At the time of Charles II restoration the

Established Church regained its former powerful position in the government

of the country. The Irish Parliament passed the Act of Uniformity in 1665

which indicated that "every schoolmaster keeping any public or private

school and every person instructing or teaching any youth in any house or

private family as a tutor or schoolmaster shall subscribe the declaration or

acknowledgement following." The penalty for non-subscribing was the loss of

the school.

| "I A.B. do declare that it is unlawful upon any pretence

whatsoever to take arms against the King . . . and that I will conform to the liturgy of the Church of Ireland as it is now by law established." |

The above is followed by another section of the Act which required every schoolmaster or tutor to take the oath of allegiance, and supremacy, before permission to teach would be given by the Bishop.

It is a matter of historical fact that at this time, Presbyterian ministers supplemented their income by starting, or continuing, a school in their parish. The Presbyterian minister, in Drumbo, at the time, was Henry Livingstone who was an avowed critic of the Established Church. He had been evicted from his church in Drumbo in 1661 for not submitting to ordination by a Bishop. There is no evidence which suggests that there was a school in Drumbo as early as this but, looking at the evidence from other areas it is more than likely that there was. If this were the case, the school would have been lost because Livingstone. or any Presbyterian teacher, would certainly not have subscribed to the Act.

Presbyterians have always clung to the necessity of maintaining an educated ministry and because of the persecution they were experiencing at this time classical schools or academies, sprang up throughout the country. The first of these schools was founded by the Rev. Thomas Gowan in 1670 in Antrim. Mr. Gowan was the father of the Rev. Thomas Gowan (Jnr.) who was minister in Drumbo Presbyterian Church from 1706 to 1717.

Two reasons can be given for suggesting that there could have been a school in Drumbo at this time. Firstly, Gowan would have had first hand knowledge of the benefits of education, seeing his father at work in the school at Antrim. Secondly, the ministerial profession in the 18th Century was more respectable than lucrative and payment of stipend often fell in arrears. It was little wonder that ministers had to supplement their living by farming or teaching. Most of the schools they operated were conducted in the Session room or in the minister's own house. These little schools, or academies as they were sometimes called, were necessarily fleeting, but valuable work was done in them.

Probably the earliest reference to education and to there being a `school' in Drumbo was made in 1785. The Rev. James Malcom who was minister in Drumbo Presbyterian Church had a son by the name of Andrew, and among the Malcom MSS there is a reference to Andrew Malcom and to the fact that "he was educated privately in the neighbourhood of Drumbo and Lisburn." Whether or not his father was the teacher is not recorded.

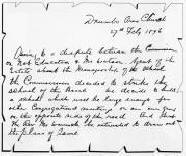

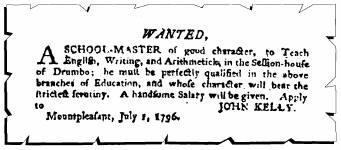

It is more than likely that any education that had been

available up to this time in Drumbo was conducted in the Session House

connected with the Presbyterian Church in the village. Certainly the

following advertisement for a teacher for Drumbo school, in July 1796, would

confirm this.

|

|

| An early advertisement for a teacher in Drumbo in 1796. | Second Report of the Commissioners of Irish Education Inquiry 1824 |

The 18th Century, witnessed rigorous enforcement of the laws against education and rendered teaching a dangerous calling. This would appear to be the reason why popular education, through Hedge Schools, became prominent. The Hedge School owes its origin to the laws against education and its name to the practice of keeping school under the sunny side of a hedge. These were pay schools and, in many cases, through their great love of learning, parents were prepared to pay for the education of their children more than their limited circumstances would permit.

Because the law forbade schoolteachers to

teach they were compelled to give instruction secretly. The law also

penalised householders who allowed teachers to use their premises, so the

teacher was forced into a remote spot out of doors, weather permitting.

Therefore, the sunny side of a hedge or bank, which hid the school from the

eye of a passer-by, would have been chosen. Sometimes a pupil was put on the

look out for the approach of a stranger or of a person who might be judged

to be an informer. If such a person appeared, the school dispersed for the

day; but it would always meet in some place else the following day. In this

way the Hedge School became the recognised channel for surreptitious

education in country districts where:

| " . . . crouching `neath the sheltering hedge, or stretched on mountain fern, the teacher and his pupils met, feloniously to learn." |

During the winter months the schoolteacher moved from place to place living upon the hospitality of people, earning some money by turning his hand to farm work or, if he dared, by teaching the children of his host.

Later, when the laws against education were somewhat less strictly enforced, school was held in a cabin, a barn, the home of the schoolteacher, or any building that might be given or lent for the purpose, but the name "Hedge School" still remained until well into the 19th Century.

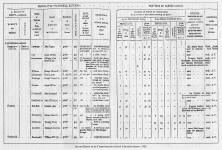

The first official reference to a Hedge School in Drumbo can be found in the Second Report of the Commissioners of Irish Education Inquiry. This census of schools was taken in 1824 and reported on in 1826-27, and gives the following information about the school in Drumbo.

We know, from church records, that the Session House was not very spacious.

It would only have been designed for about twenty men in which to hold

meetings. To have forty or more children in it all day would have been very

cramped, although, attendance was not compulsory and was very irregular.

Even though the census return gives an average attendance of forty children

it can be assumed that there could have been up to twice this number on the

register. However mean the school building, and however great the bodily

discomfort of both teacher and pupils, the atmosphere in the Hedge Schools

was very much work related. The people wanted education for their children

and they ensured that they got it.

The willingness of the people to make sacrifices for the education of their children, and their co-operation with the schoolteacher were undoubtedly factors which helped the Hedge Schools to flourish. The schoolteacher had to take what he could get; any shelter was better than none, and what was obtained was usually given freely.

There are no records to inform us where James McKee, the teacher at the time, came from, but the surname McKee is a name with a long history in this area. Whether he came from the area, or to the area, is unclear. The position of the hedge schoolteacher was very tenuous and he was liable, at any time, to be deposed by a younger and and more able teacher. When a pupil had learned all that his local teacher had to give, he issued a challenge to the teacher to meet him in a contest of knowledge before competent judges. If defeated, the pupil would remain under his old teacher, but if victorious, he would go on to another school where he would continue his studies. Again a contest would take place with his new teacher; and once again, if victorious he would move on to another school. In this way the pupil increased his stock of general information, acquired real knowledge, and became more subtle in the art of argument and debate. After a year or two the pupil would return home to his old school and again challenge his first teacher. If victorious, the pupil would then take over the school and the teacher was compelled to move on to another district. This may well have been how James McKee arrived in Drumbo! From all accounts McKee must have been held in fairly high esteem by the people, because records show that he was also the teacher in the school at Carr at the same time. Whether McKee had assistants to help him run the two schools or whether they were only open on certain days of the week cannot be said with any degree of accuracy. His social standing among the people whose children he taught would have been remarkably high. The people would have regarded him as one of themselves, but different in the respect that he was a man of some learning. They regarded him as a friend whose counsel was sought in difficult circumstances and whose decisions in important matters carried weight. No function of consequence, wedding, baptism or harvest home took place at which he was not a prominent figure. Although his social prestige was immense, his income from all sources was small. At this time, James McKee had an annual income of 20 pounds from the children in Drumbo. He would have been charging parents about 2 shillings per quarter for reading lessons, Is. 8d per quarter for spelling and between 4 shillings and 7 shillings for arithmetic for the same period. In the majority of Hedge Schools at that time reading, writing and arithmetic were the only subjects taught and, for the children who attended them that was about all they needed.

Very little is known of the system of teaching in

the Hedge Schools, although, a member of the Commissioners of the Board of

Education in 1825 complained of the "mechanical and laborious methods by

which the memory is exercised" adding that "the understanding and moral

powers of children" seem to have no claim upon the teacher's attention.

However, the kind of text-book used in the schools is a fairly good

indication of the teaching methods employed. In some text-books which have

survived there are examples of lessons in `The Elements of Spelling' which

cite "the most common and general sounds of the letters, which children

should be habituated to, before they enter into the various changes of sound

which the same letters should have." The books also advance the theory that

"spelling came before reading. It is a fine thing to know how to read; but

we must know how to spell first! We cannot read until we can spell." After

the children had recited long lists of words and which they were expected to

master came the hope "now that 1 have learned to spell better; I hope I

shall be able and may read better now." Much of the work done was by oral

repetition, or rehearsing, and reading was done by what might be termed the

individual method for each child. This meant each child reading to the

teacher from whatever book was available; there was no such thing as an

individual reading book. Some of the books read were simple stories, fairy

tales and some were full blooded biographies of highwaymen and others that

were not at all suitable for children or young people to read. Children

brought from home whatever book they could find or was given them; and any

alleged harm these books did to the children was more than compensated by

their success in learning to read.

The teaching of arithmetic appears to have been more structured and systematic. Text-books of the time indicate - rules being clearly given, followed by two sets of examples; the first of which consisted of carefully graduated problems while the second contained more difficult questions. The books also showed correlation of arithmetic with other subjects such as Chronology, History and Mechanics. The author of the book had much faith in its application as he concluded: "I rely upon the event of any trials that may be made upon boys of the higher and lower classes in Ireland, in which I am certain it will be found that not only the common, but the higher parts of arithmetic are better understood and more expertly practised by boys without shoes and stockings, than by young gentlemen riding home on horseback, or in coaches, to enjoy their Christmas idleness."

Discipline was thought to be severe in the Hedge Schools. "The obligation to silence, though it may give the master more ease, imposes a new moral duty upon the child." James Nash who was an old hedge schoolmaster told his friend Thomas Meagher: "My school is below there, and 1 flog the boys every morning all round to teach them to be Spartans." The extent of the punishment which Nash administered is not known, but, like most other schoolmasters of his day, he would evidently take no excuses for the neglect of study.

The working of the Hedge Schools at that time is described in records kept by a teacher of his day's work: "Our school begins precisely at ten o'clock in the morning for we cannot begin earlier, as many of the children come from a distance. Every child must be in his seat by that time. I then open the school by reading a Psalm or Hymn. After that, they all repeat a task to me, of grammar or spelling, and then a lesson in classes, for I have them all classed together according to their several abilities. About twenty of the children write on paper with quills, twenty on slate and twenty on sand. After writing they all have a lesson, and a task of scripture verses which they commit to memory. The labour of the day is concluded by reading a Psalm and making a few remarks of a religious nature, suitable to the subject, and adapted to their capabilities, to which they listen with great attention."

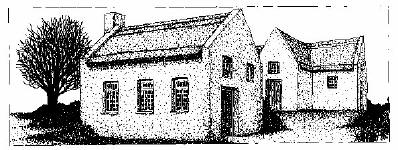

This fairly unstructured form of education continued in Drumbo up until 1840; despite the introduction of a National Education Board throughout Ireland in 1831 and the building of a new schoolhouse, in 1836 in Drumbo, at a cost of 97 pounds paid by local subscription.

The Ordnance Survey Memoirs record the attendance of 63 pupils in Drumbo in 1836; 40 of whom were male and 23 female; and all Protestant. 23 of the pupils were under ten years of age, 1 was over fifteen and 1 over forty. The "master" was a Presbyterian.

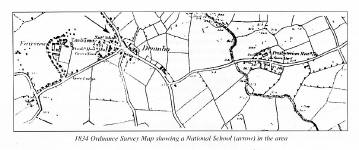

It may be that this new school was a replacement of a previous one. Evidence for this comes from an Ordnance Survey Map of 1834, which clearly shows a National School in Drumbo on the site of the proposed school to be built in 1836.

The National Education Board, set up in 1831,

was an attempt to co-ordinate the education of young people and one "which

requires that all teachers henceforth to be employed be provided from some

model school, with a certificate of their competency, will aid us in a work

of great difficulty, to wit, that of suppressing Hedge Schools and placing

youth under the direction of competent teachers, and of those only." The

salaries of the teachers were to be paid by the Board who were also to be

responsible for the compiling and publication of school books. Grants were

also to be given for the building of school houses, and combined

denominational applications were to receive preference. There was to be no

reading of the Scriptures during the time set apart for secular instruction,

and the clergy were encouraged to instruct the children of their

denominations at suitable times.

The National Education Board was strongly opposed by members of the Established Church who regarded proselytism as a duty. They objected to "the exclusion of the Scriptures and the admission of a priest" into the schools to give religious instruction; and they accused the Board of "establishing Popery and promoting infidelity."

Presbyterian opposition was even greater. They held that the whole Bible, and not just extracts from it, should be the basis of National education; they objected to the Board's control over schools and teachers, and their restrictions as to school books; and they highly disapproved of allowing separate religious instruction to be given to Catholics. They even resorted to violence to close National Schools and they sought to make the education problem a political issue. As soon as the new system was announced by Lord Stanley, meetings were held in almost every town and village in Ulster. The people were led to believe that the Government were about to send round the police to take possession of their Bibles. Soon after these meetings gun clubs were established for the purpose of "furnishing the peasantry with the guns to defend their Bibles." The opposition in the North was particularly vigorous. Ministers who connected their schools with the Board were persecuted by their congregations and were nicknamed `New Board Ministers'. Schools were damaged both inside and outside. Crosses and `Ps' were painted on doors and windows and many ministers were exposed to violence.

As a consequence,

many schools, including Drumbo, were withdrawn from the Board and the

Presbyterians proposed setting up a system of Scriptural and Presbyterian

education for themselves.

As a consequence,

many schools, including Drumbo, were withdrawn from the Board and the

Presbyterians proposed setting up a system of Scriptural and Presbyterian

education for themselves.

The continued opposition to the National

Education Board on the part of Anglicans and Presbyterians soon obtained for

them a number of concessions, among which were that no clergyman of another

denomination could enter their schools and, that no child should be excluded

from religious instruction should that child wish to attend. In 1840, the

Presbyterians withdrew all opposition to the National Education Board

because by this time all their demands were conceded; they were then to

become the most ardent supporters of the Board. So on 9th April, 1840 the

following application was made by the Rev. Adam Montgomery, Patron of Drumbo

School, for readmission to the National Board of Education.

| "The name of this school is Drumbo. It is situated in the townland of

Drumbo and is adjoining a place of worship. Post town Belfast. Distance five

miles and a half to the North. It was founded in eighteen hundred and thirty

six (6) and build by private subscription. The house is twenty seven feet by

seventeen in the clear, and nine feet high on the side wall; it is built of

stone and lime, roofed with slates and well fitted up with desks. It is all

in one room and wholly employed for the use of the children. It is held by

lease, rent free - I may mention that our lease is in preparation only as

the ground was held by a subtenant and he had arrangements to make. The

school is under the management of a committee - chosen by the parents of the

children. Patron the Rev. A. Montgomery. The times for reading the

Scriptures and catechetical instruction are so arranged as not to interfere

with or impede the scientific business of the school and, no child whose

parents or guardians object is required to be present or take part in these

exercises; and no obstruction shall be offered to the children of such

parents receiving such instruction elsewhere as they may think proper. The books used are provided by the children and of the usual character employed in teaching; and the Scriptures and Westminster Catechisms are used also. The number of children in attendance is forty one - of which twenty-three are males and eighteen females. There is a register kept in the school and a report book will be kept. The children pay for reading 3d per week; for writing and accounts at the rate of three and nine pence per quarter, and for English grammar and geography at the same rate. A number of poor children (8) are also in attendance and taught gratuitously and others at low rates. The aid requested is in addition to a grant of books the sum of �8-0-0 per annum to pay for the education of the children of poor parents, many of whom are unable to send their children to school; and whatever gratuity the inspector of the Board may report the teacher so deserves." Signed on behalf of the school.

|

On 31st August, 1840, an inspector by the name of Mr. Patton visited

Drumbo school for the purpose of inspection as requested in April by the

Rev. Montgomery. He completed a report for the application of aid towards

payment of the teacher's salary and supply of books, and in so doing made

the following observations and noted that:

| The school is not in connection with or attached to the Meeting House; |

| it is sufficiently ventilated and warmed: |

| there are 5 desks and forms attached, with a teacher's desk and chest for books accommodating 80 pupils; |

| the teacher was Mr. John Bailie, aged 20 years, who had not received any instruction in the art of teaching but, who was leaving. A well qualified teacher will be appointed in a few days; |

| the inscription "National School" will be put conspicuously on the school house; |

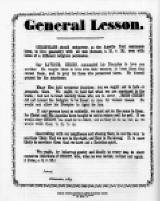

| the General Lesson of the Board will be hung up in the schoolroom; |

| the books of the Board will be used in the school; |

| the hour from 2 to 3 on Monday to Friday will be devoted to religious instruction and also one hour on Saturday; |

| the expected increase in pupil numbers was 40; 25 males and 15 females; |

| He then concluded "the circumstances of this school are so satisfactory that I would recommend its immediate adoption by the Commissioners of the Board." |

Consequently, Drumbo was connected to the National School

Board on 24th September, 1840, and they granted salary to

the teacher John Bailie and monies for text books for 75

pupils. The textbooks employed were issued by direction of

the Board. They were, for the period well illustrated and

bound; and were sold to pupils for a few pence and in

certain necessitous cases given gratis. Because they were in

continual use they were usually passed on from the older

members of a family to the younger, and even from parent to

child.

|

Issued from 1835 onwards by the

Commissioners of National Education in Ireland with the

requirement: |

Because Drumbo had been out of the National System of Education, John Bailie, the teacher, had been appointed by the manager of the school, Mr. Calwell and his salary would have been paid by the pupils for the instruction he provided. Following the granting of aid, by the Board, they paid John Bailie �3.0.0 on 3rd June, 1841, for five months instruction up to September 1840. The Board also paid Stewart Carse �2.13.4 for four months instruction during the same period. During this period the school was closed for one month "with the permission of the committee"; no reason for the closure was given. It would appear that Bailie and Carse taught in the school until Bailie left in October 1842 and, Carse in December of the same year. Carse had been paid �8.0.0 per annum, paid half yearly. Upon Bailie's departure, Samuel Graham was appointed to the school and was paid �4.0.0 on 28th April, 1843 for instruction since his appointment in October. Records don't show how long Graham stayed in Drumbo, but in 1848 William Dorman was appointed as teacher in the school and he remained until he resigned on 3rd March, 1849. The appointment of Graham's successor appears to have been a situation fraught with difficulties, as on 16th May, 1849 the National Education Board received a resolution from Mr. Calwell, the manager of the school, on behalf of the school committee, stating that they had:

... appointed him as Patron and manager in room of Rev. A. Montgomery who has resigned."

The resignation of the Rev.

A. Montgomery appears to have been prompted by the

appointment of George Brydon as teacher in Drumbo on 8th

May, 1849 for whatever reason.

The situation was serious enough for the Board to send out

an inspector who, on 4th June, 1849, reported that:

". . . the school had been closed from 3rd March when William Dorman resigned and was re-opened on 8th May when George Brydon was appointed."

The National Education Board was requested by Mr. Calwell, the manager, to appoint Mr. James Robinson as temporary manager, from 29th September, 1851 "during my absence abroad for the winter."

In spite of the lack of other denominations in Drumbo, numbers were rising and an application from Mrs. Bessie Calwell to the Board for financial assistance for the salary of an assistant teacher on 29th June, 1861, indicated that the school "was being enlarged at present," from the initial 27 feet in length to 37 feet. The application goes on:

"There is only one room in the schoolhouse used by the three teachers employed namely - William Watson, Charles L. Horne and Hannabella Watson (alias Caughey). The application for financial aid is on behalf of Hannabella Watson, aged 18� who commenced teaching in Drumbo on 3rd June, 1861, having taught in Ballymacbrennan as an assistant and work mistress from May 1859 till 29th September, 1860. She was classed (I1I'-) by the Inspector. There are 78 males and 54 females on roll and the average attendance for the last six months has been 44.9 males and 25.2 females."

The inspector for the Board Mr. William Molloy, who replied to the application, came to Drumbo on 22nd August, 1861 and included in his report that:

"The principal is William Watson II2 and the other teachers are Thomas Entwistle a probationary assistant, and Hannabella Watson who is of good character. There are now 94 males and 65 females on roll; the average for the last four months was 46 males and 30 females and there are 89 children present today - 57 males and 38 females."

The report concludes that:

"Owing to the number of girls in attendance a female assistant is much required. As the average attendance (76) warrants a second assistant being recognised I beg to recommend that this application be formally entertained."

In 1863, the estate owned by Mrs. Calwell on which Drumbo National School stood, was sold, and the new owner was Robert Batt of Purdysburn. Anticipating a continuation of the cordiality extended to them by the Calwells, the Church Committee did not formally lodge any claim to the school or its grounds. In so doing they put themselves at the mercy of the new landlord and his successors for all time.

However,

the Church Committee was not interfered with in the

management of the school until 1874 when, during a General

Election campaign the manager of the school, Mr. W. J.

Watson, accompanied by the Bailiff, arrived and demanded the

use of the school for the purpose of holding a political

meeting. A member of the Church Committee, who was present

at the time, referred Mr. Watson to a rule of the National

Education Board which prohibited the holding of such

meetings in any school receiving financial aid from the

Commissioners. Thus commenced a protracted and unfortunate

period of time in the life of the school. Mr. Watson did not

take too kindly to such an attitude and promptly served the

principal Mr. Robert Entwistle, with a notice of dismissal.

The Church Committee refused to part with his services,

which he had given since his appointment on 1 st August,

1870, and where forced to the necessity of dismissing Mr.

Watson, as manager, and appointing another one in his place.

The Church Committee were then served, by Mr. Batt, with a

notice to give up possession of the school. They refused and

were finally ejected from the premises. The Morning News of

18th February, 1876, gave the following account of their

ejection:

| `On Wednesday last the Sub-sheriff of the County, accompanied by Mr. Batt's agent, Mr. W. J. Watson, and the Bailiff, appeared at the school. The children were summarily dismissed, and the work of disembowelling the school began in true earnest. The old forms, carved with many an urchin's name, were speedily deposited on the public road. The teacher's desk was dragged after them as unceremoniously as if it had been tainted with the leprosy of dissent, and the harmonium, occasionally uttering a gruff note of remonstrance, was conveyed to the shelter of an adjoining hedge. Then followed in quick succession maps and tablets, slates and pencils, clock and ink bottles, etc. The books were flung into a capacious bag and conveyed upon the sturdy shoulders of the Bailiff to the nearest public house, and last of all, the very fire was "ejected" and its smouldering embers thrown into a gutter on the roadside. Meanwhile the simple-minded people of the village ventured out of doors, and stood watching the proceedings with feelings of awe and wonder. "Old age forget its crutch, labour its task," and all ran to behold the mighty doings of "the office," while now and then travellers passing that way stopped to make enquiry, and old men whose geographical knowledge had become deficient, were afforded the opportunity of examining the maps and tracing out the locality of the Suez Canal. At length, when the school apartments had been thoroughly gutted, and everything movable thrown out, the Bailiff paused to wipe his heated brow, and the agent, Mr. William James Watson, stood and looked around him with the air of a conqueror. Their work was done. By this time the Sub-sherriff and agent were moving away, and the onlookers expected that the Bailiff would also retire from the scene and follow them at a respectful distance. But in this they were disappointed. After a brief consultation, the two former gentlemen returned, and the Bailiff, who had imagined his toil was over, was ordered to commence afresh, and to convey the unoffending articles, now bespattered with mud and slush, back to their former resting-places in the schoolroom. When with the assistance of the teacher, who now declares himself only the servant of "the office," this work was accomplished, the interesting proceedings terminated, and the crowd of onlookers dispersed, wondering among themselves at that which had come to pass, and asking the ominous question, "what next?" |

Following this eventful day Mr. Watson was left in undisputed authority as manager of the school. But because he was not a resident of the district and, consequently unable to be in a position to discharge his duties, of manager, appropriately, the Commissioners for National Education decided to appoint a local manager and suggested the Rev. W. J. Warnock as being particularly well suited for the position. However, the new owner of the estate, Mrs. Way, being an Episcopalian herself, was determined to have an Episcopalian appointed, despite the wishes of the Board and the fact that of' the 70 children on roll in the school, 65 were Presbyterian. Subsequently, the Commissioners for National Education decided to withdraw financial aid from the school and it closed down, albeit temporarily, in August 1876. With the permission of the Commissioners the school was transferred to Rokeby Hall, where accommodation was kindly given by Mr. .1. D. Dunlop, for a period of about two weeks.

What happened during those two weeks to heal the

rift between the two parties hasn't been recorded but, the

school was reopened by Mr. Batt on I Ith September. The

following is the report that Mr. Watson, the manager,

submitted to the National Education Board when he made

application for financial support to be given by the

Commissioners:

| "Drumbo "Mixed" School.

Nearest post town is Lisburn, distant 3 miles west.

The house is in good repair and has been for many

years used as a school house. There is only one room

37 feet by 17 feet. The furniture comprises 10 desks

with seats attached and 4 separate forms all in good

condition. The teaching staff consists of Robert Entwistle, principal, aged 29, whose salary was �20 per annum, Caroline Entwistle, assistant, aged 22 and Margt. Milby paid monitor, aged 16. The number of children on roll was 125 and the average daily attendance for last year was males 27.7, females 26.3. Total 54. School hours are from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. Religious Instruction is imparted in accordance with the rules and regulations of the National Board from 10 to 10.30 each morning. The books used for combined literacy instruction arc those published by the National Education Board and supplied by them from their depot in Dublin. Pupils pay between is-ld to 3s-6d which is regulated by the principal.#The school is open for admission of visitors at any time between the hours of 10 a.m. and 3 p.m. The Patron of the school is Robert Narcissus Batt, Esq., Purdysburn, Belfast. The Manager is William James Watson, Aughavilla Lodge, Warrenpoint. The amount of local aid independent of sums raised by the Poor Law Guardians in accordance with the late Act amounts to about �20 annually. The house is that in which the Drumbo National School (Ref. No. 2561) was conducted, and it is now carried on by the same staff of teachers. The former school was closed by direction of Mr. Batt on 28th August, 1876, and opened as a new school on 11th September. Application was made to have the school readmitted on roll on 14th September, but no notice was taken of the application till application was again made on 11th October." |

During this period Mr. Thomas Allen was appointed

Principal in 1883 at the age of 28. He inherited much of

the unpleasantness which had gone before, and which was to

continue until 1896 when:

Two members of Church Committee were delegated to visit in each townland to -solicit the members of the congregation for subscriptions towards the building of the new schoolroom and lecture hall."

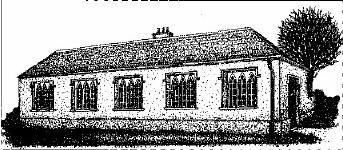

Plans for the new schoolroom and lecture hall were completed by the end of May 1896 and tenders were sought immediately.

A Committee meeting on

9th July, f896 considered four tenders f-or the erection

of the new school. After careful deliberations it was

proposed and passed that the estimate of- Mr. Robert

George of York Lane, Belfast, for the amount of-�520 be

accepted. However, at a meeting of Committee on 20th

August, 1896 the question was posed "How and when are we

going to get money for the new school?" Mr. Thomas

Crawford, a Committee member, offered to lend the money at

the same rate of interest charged by the bank. This offer

was accepted.

The building of the new school was rapid, in that most of

the building was completed before the laying of the

foundation stone. The foundation stone was laid on 14th

November, f896, by Miss Rowena Brown, Edenderry.

The

following entries commencing with a date, are quotations

gleaned from Drumbo Presbyterian Church Committee minutes

pertaining to the school:

| 15th February, 1897 | - "It was agreed that half a ton of coals be got to burn in the new schoolroom to help to dry it." |

| 3rd October, 1904 | - "Mr. Thomas Allen was given liberty to get a stove for the schoolroom provided he could raise the necessary funds." |

| 5th July, 1909 - | "When it was unanimously decided to get the walls of the schoolroom coloured and the window frames painted." |

| 13th August, 1912 - | "The Commissioners of National Education allowed �2 towards heating and cleaning the schoolroom. It was decided that the teacher be allowed �1 for lighting and cleaning." |

| 3rd September, 1917 | - "Rev. Mr. Cordner reported that a stove was required in the school to enable the teacher to proceed with the cooking class. Liberty was given to supply one. Mr. Cordner suggested that the children attending the school might be asked to collect from friends so that a considerable amount of the necessary cost might be raised. Some new desks were also required - Rev. Mr. Cordner and Mr. Hunter (teacher) were given a free hand to do what was necessary. Managers expenses connected with the appointment of a Principal Teacher for Drumbo N.S. amounting to �2 was passed unanimously." Mr. William Todd was appointed Principal in 19f8 at the age of 44. |

| June, 1918 - | "Mr. Connery was

deputed along with Mr. Todd (teacher) to select the

desks necessary for the schoolroom. It was unanimously decided that the committee contribute �1 annually towards the cost of cleaning the schoolroom and also to contribute �3 annually (if funds were available) to aid teacher in paying rent for dwelling house." |

| September, 1919 - | "It was also suggested that the pupils in the day school be asked to contribute towards the heating of school." |

| December. 1919 - | "A discussion arose as to how a residence for the teacher could be secured: Various suggestions were made. It was finally suggested to build a house for the sexton and make his (sexton's) house the teacher's residence." |

| 6th June, 1920 -

|

"A letter was read from Mr. Todd (teacher) asking that a guard be provided for the stove in the schoolroom, also a press to hold science apparatus" |

| 11th June, 1921 - | "The condition of the lavatory in connection with the day school was discussed, finally it was agreed that Mr. Cordner was to have a talk with the teacher concerning the matter. The Committee to inspect the school grounds to see if a suitable place can be found for the erection of a house to hold coke for day school. That the pupils of the day school be asked to contribute �5 a year for coke and coal." |

| 3rd August, 1924 - | "A special meeting of Committee was held to consider the advisability of proceeding with the renovation of the school room during the school holidays. It was unanimously decided to go on with the work." |

| 15th February, 1926 - | "Store in school to be overhauled. It was suggested that keys should be got for the organ in school and also for coke house. Application form signed for grant from Regional Committee for proportion of expenses of day school upkeep." |

| 26th April, 1927 - | "School Inspector suggested a fire screen for school in classroom and also that accommodation is not adequate." |

| 5th March, 1928 - | "After discussion it was agreed that the school premises be transferred to the Education Authorities of the Government of Northern Ireland." |

| 12th November, 1928 - | "After considerable discussion it was agreed to get a transfer form from the Ministry of Education - meet on Monday at 8.00 p.m. and try to come to a decision on the matter." |

| 19th November, 1928 - | "The school transfer form from the Ministry of Education was submitted and read over. After full discussion some members voted for the transfer of the school on a ten year lease. Some wanted absolute transfer and some were neutral." |

| 15th April, 1929 - | "The agreement for transfer of Drumbo P.E. School to County Down Education Authority was submitted and passed to be signed by the Church Trustees after approval of the congregation." |

| 23rd March, 1931 - | "The following were appointed as School Management Committee till July 1932: Rev. J. B. Wallace, Thomas J. Graham, Joseph Bingham, Robert Martin, Hugh Shortt." |

| 5th October, 1931 - | "Mr. Wallace reported that the sexton, John Patterson, had been appointed caretaker of Drumbo P.E. School at 7/6 per week for 52 weeks from 1st September, 1931." |

| 24th February, 1932 - | "The Agreement, as prepared by Mr. George Allen, solicitor, was read over. It was agreed that before getting it signed the secretary would ask Mr. Allen if the words "without extra pay" should be inserted after the sentence "give three whole days". Mr. Wallace to write Regional Committee and see if the necessary alterations required would be made in the school, or an extension of the lease for 25 years from 1940, and also enquire if an absolute transfer were made, could the school be transferred back again on eighteen months notice, if the conditions of transfer were not carried out by the Government." |

| 4th April, 1932 - | "After considerable discussion it was unanimously agreed to make an absolute transfer of the school to the Regional Committee, and call a meeting of the congregation after a morning service at the earliest date and ask their approval; explain that a clause would be inserted in the Transfer Agreement whereby the school would be transferred back to the church on eighteen months notice if the Government failed to carry out any part of the Agreement, or the premises ceased to be used as a P.E. school." |

| 9th May, 1932 - |

"Mr. Wallace reported that the

absolute transfer of the school had

been agreed to by the Regional

Committee." Following the retirement of Mr. Todd in 1938, Mr. Robert Morrison was appointed Principal at the age of 25. His period in Drumbo included the evacuation of families, to Drumbo, from areas of Belfast. This movement increased, quite dramatically, the pupil numbers in the school and put much pressure on what the School Inspectors of the time where calling "very inadequate accommodation." |

It was this situation which Mr. Herbie

Currie inherited, when he was appointed

Principal in 1945, at the age of 26.

| 11th February, 1951 - | "Giving notice that foundations had been laid for a new classroom in the school grounds, Mr. Miskelly asked if the Ministry had received official authority from the church and would this building, when erected, prolong the time until the proposed new school would be built." |

| 19th February, 1951 - | "On a

matter arising out of the last

minutes Mr. Wallace outlined the

conditions under which the Ministry

of Education were carrying out the erection of an additional classroom. These were: I . These extensions would have no restraining influence on the proposed new school building project. 2. When the Ministry do vacate

the present school building the

church would have the option of

purchasing the extension if they so

desired. |

| 28th

June, 1954 - |

"After a lengthy discussion on how

best the Session and Committee

could use their influence to

advantage, thus possibly speeding

up the present delays which seem

to exist regarding the erection of

the proposed new school. Members

present expressed the view that a

deputation should approach the

Director of Education, stressing

the point that daily attendances

were still increasing, even to the

extent that a fourth teacher was

shortly to he appointed, and due

to lack of accommodation would

have to occupy the platform." However it was not until 1959 that Drumbo was to get the much promised and long awaited |