|

|

| By Neville

H. Newhouse |

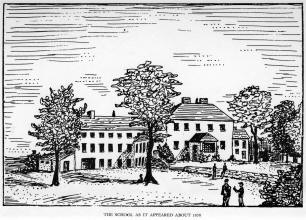

The School as it appeared about 1850 |

TO ALL WHO HAVE PLAYED A PART IN THE STORY

For a school founded to provide `guarded' education for the children of a

numerically small Christian community to have survived for two hundred years

is no mean achievement. To have grown into a relatively large school serving

the educational needs of a wider local community is perhaps a greater one.

Neville Newhouse has admirably drawn together the threads of this

chequered history with fascinating glimpses of what life in the school was

like at different periods of its development. To read of the crises that

challenged the staff and governors at decisive moments and how they were met

can only inspire admiration at the faith and courage of those who laboured

to hand on a live torch to the next generation.

In particular the record of two exceptional partnerships in the persons

of Joseph and Mary Radley and of John and Norah Douglas reveal how committed

Friends gave the best part of their lives to the re-creation of a vital

tradition. While a school still stands on Prospect Hill, these names should

be remembered with thankfulness.

The story ends with the retirement of John and Norah Douglas, because it

would be a rare historian who could evaluate the developments in which he

himself had played a vital part. The story of the years from 1952 to 1974 is

wisely left. These were the years when Ivan Gray, Neville Newhouse and Arthur

Chapman were' to occupy the post of Headmaster, and when the school was to

undergo decisive changes.. On Ivan Gray's initiative and with some hesitancy

from the Governors, the school entered into a partnership with the state in

a way which was not open to the Quaker schools in England. Neville Newhouse

in his term of office carried through the major part of the necessary

building programme and developed a strong academic tradition. The changed

character of a school in which the boarders are less than 10 0/0 of the

total enrolment has perhaps made the task of preserving the Quaker tradition

more difficult.

|

|

|

| C. Ivan

Gray |

Neville H.

Newhouse |

Arthur G.

Chapman |

However, new times and new challenges face the school. The debate on

comprehensive education now confronts the voluntary schools. The communal

conflict in N. Ireland has raised the issue of integration. In meeting these

problems two quotations from George Fox the founder of the Religious Society

of Friends should be remembered. `There is one, even Christ Jesus, that can

speak to thy condition'- a precept that must be combined with his advice to

his followers `to walk cheerfully over the world, answering that of God in

every man'.

March, 1974

DESMOND G. NEILL,

Chairman of the Board of Governors.

This history should have been written by John M. Douglas who had

unequalled knowledge of the School and of Irish Quakerism. The work was

often in his mind after he retired, and he did gather together a great deal

of material, some of which he was persuaded to tape-record not long before

his death ; a great deal more was stored in his mind and never saw the light

of day. His widow, Norah, kindly allowed me to make considerable use of his

papers.

So many Ulster and Irish Friends have helped me that I cannot name them

all here. But I must thank the Advisory Committee of George R. Chapman,

Arthur J. Green, G. Leslie Stephenson and Henry John Turtle who have from

the first encouraged and guided me, and also Arthur G. Chapman, the School's

Headmaster, who has been my link with the Appeal Committee which has seen to

the publication in time for the bi-centenary year. The judgments on events

and people, like the shortcomings, are, I need hardly say, entirely my own.

The only previous history of the School was written in 1935 by Mary

Waterfall, the daughter of Joseph Radley. Almost all the other source

material is to be found, well catalogued, in the Strong Room of Lisburn

Friends' Meeting House in Railway Street. In general, I have indicated

sources in the course of the narrative, rather than in footnotes and

cross-references. The first chapter has already appeared at greater length

and fully annotated in the Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of

Ireland (1968 Volume No. 98 Part 1), to whom I am grateful for the

permission to publish this shorter version. Thanks are due also for the

appendices, the photographs and the index, which are the work of Henry John

Turtle helped by Betty Calvert.

CHAPTER ONE

Beginnings

Friends School, Lisburn was founded - though not under that name -

because in 1764 a prosperous linen merchant, John Hancock, left �1,000 for

the purchase of land in or near Lisburn on which to build a school for the

children of Quakers. This part of his will reads

Item : 1 leave and bequeath to my loving Friends Thomas Greer, John

Christy, and my loving kinsmen Robert Bradshaw, and John Hill, one thousand

pounds sterling, in trust for this special viz : to purchase Lands therewith

and the Rents and Proffits thereof to apply to establish a School within the

present bounds of Lisburn Men's Meeting for the Education of the Youth of

the people called Quakers, the master thereof to be a sober and reputable

person, and one of said people, and the school to be under the Inspection of

the Quarterly Meeting of said people for the Province of Ulster.

In making this bequest John Hancock showed himself to be a good Quaker.

For ever since George Fox had established a school for boys and girls at

Waltham Abbey, and a school for girls only at Shacklewell, the Society of

Friends in both England and Ireland had set great store by education. Even

so, their schools did not on the whole prosper, the many new ones they

opened being scarcely sufficient to replace those which were always closing.

As early as 1687 the National Quaker Meeting of Ireland passed a minute

telling schoolmasters `not to lay down their schools without the consent of

the men's meeting to which they belonged'. The appeal was ineffective.

Schoolmasters were in very short supply, and Quakers often `put their

children to the care of others that were not Friends', as a minute of 1725

expressed it. John Hancock was one of the many who deplored this state of

affairs ; and one of the few who were determined to alter it.

A letter he wrote in 1764 to his friend Thomas Greer shows that the

founding of a school in `our poor Province' had been in his mind for some

time. His hope was that Friends throughout Ireland would provide a house in

Ulster, in which event John Hancock and local Quakers `would endeavour to do

the rest amongst us'. Lisburn, he said, seemed `the properest place', first

because he had `particular attachments thereto', and second because it was

`a soil and situation a school will thrive best in'. Keen though he was to

see it established in his day, he knew that his poor health made the hope

unlikely. So he ended his letter to Thomas Greer with an obvious reference

to the will he had made three months earlier

... my state of health will not allow much solicitation or engagement of

mind about it. I leave it to thee - I would rejoice to see it in my day, but

if that be not permitted, when my memorial

[i.e. will] shall have manifested the disposition of my heart, perhaps

someone may be spirited up to promote it.

Eighteenth Century Lisburn

It was not surprising that John Hancock thought Lisburn `the properest

place' for his school, as it was by 1800 greatly admired by many travellers

-`esteemed one of the handsomest towns in the kingdom', according to Richard

Shackleton, headmaster of the school at Ballitore. It had twice needed

rebuilding, once after the '41 rebellion and again after the great fire of

1707 when its reconstruction coincided with its gradual establishment as the

centre of the linen industry in the Lagan valley. Its four thousand odd

inhabitants occupied, according to John Gough Junior who wrote `A Tour of

Ireland 1813-14', an area round the market square which made it `the

handsomest country inland town' he had seen in Ireland, one `hardly to be

equalled in England' for that matter. There were three principal streets,

Castle Street, Bow Street and Bridge Street, Castle Street being

particularly impressive with modern, 3-storey houses lining a well-paved

clean roadway. The present Railway Street (called in the early 1700's

Schoolhouse or Schoolroom Lane and by 1800 Jackson's Lane) was then one of `severall

lanes in the town which, with few exceptions, consisted of thatched cabins'.

The Quaker Meeting House, also thatched and approached by a long narrow path

between gardens, had wonderfully escaped destruction by the 1707 fire. In

1776 it was, the records tell us, `a small, neat building for about one

hundred and fifty people, always filled on Sunday'. The areas which by 1900

were the sites of the railway station and the Wallace High School were both,

it need hardly be said, unspoiled fields outside the town proper, which was

overlooked by Prospect Hill whose slope is now climbed by the Magheralave

Road. The road north-west to Belfast ran through `fine houses, plantations,

church spires, bleach greens and a great number of neat whitewashed cabins

at the road side'. It led to a town four times larger than Lisburn,

similarly thriving, and already having the makings of the future provincial

capital.

John Hancock, it should be said, had English forebears who had settled in

Lisburn before the '41 rebellion. In 1757 he and his brother had inherited

considerable family business interests. He married twice and at his early

death in 1766 left a 4-year-old son who, when the time came, also handled

the business successfully, and had also for a time much to do with the

school. By the terms of his father's will he was to remain in Lisburn until

he was 8, was then to attend an English Quaker school, and thereafter to be

apprenticed to a dependable Quaker, all of which stipulations were duly

carried out. So, too, was the setting up of the school, an achievement

brought about largely by Thomas Greer, whom John Hancock had named first of

the four Quaker trustees chosen to administer his estate and to whom he had

appealed in the letter already quoted. Perhaps, John Hancock had 2

written, someone would be `spirited up' to promote the school he so deeply

longed to see : `I leave it to thee'. He had chosen his man well. Stubborn

and quarrelsome Thomas Greer may have been, but he was a passionately active

Quaker, was as convinced as John Hancock of the need for a boarding school

in Ulster, and now devoted his considerable energy and skill to seeing it

established.

Buying the Land

John Hancock's bequest was for the purchase of lands on which to build a

school, and buying land anywhere about Lisburn meant negotiating with the

Earl of Hertford whose Killultagh Estates (60 thousand acres of fine land in

County Antrim from Magheragall and Aghalee in one direction to Lambeg and

Derriaghy in the other) had come to his family from the Conways in 1609. The

previous Earl had shown little interest in his Irish land, but the present

one, with whom the trustees were to treat, was very different ; he paid

occasional visits to Ireland and was much concerned with the good order and

development of Lisburn and district.

The trustees interested themselves in 20 acres of land a quarter of a

mile to the north of Lisburn in an area known as Prospect Hill. These fields

overlooked the town and ran down to Jackson's Lane and the Quaker Meeting

House. Presumably the trustees had first satisfied themselves that the

tenants would be willing to leave their holdings in favour of John Hancock's

Quaker school.

Early in 1776 an approach was made to the agent for the Hertford Estate,

and Robert Bradshaw reported to Thomas Greer that he and others `waited on

William Higginson Esquire'. The Earl of Hertford was in Lisburn on his own

affairs and the Trustees asked his agent to present their written request.

There must have been some argument with William Higginson, but eventually

the trustees `prevailed on him to go and prefer our proposals which he did

about ten o'clock'. After an hour William Higginson came out again to say

that the Earl would not entertain the idea since the Quakers wanted the land

as `a thing for ever'. The agent therefore returned the paper to Robert

Bradshaw in the presence of another well-known Lisburn Friend, William

Nevill (the late John Hancock's brother-in-law), suggesting that the

trustees should `amend the proposals'. At this, Robert Bradshaw became

indignant - Quakers always meant what they said and were not prepared to

bargain. He sent a letter to Thomas Greer ending with the words

. . . on the whole we must now quit thoughts of having the school settled

within the bounds of Lisburn Meeting. I need not tell thee what a

disagreeable task it is for me to write thee in this stile.

Far from `quitting' this scheme, Thomas Greer saw it through within two

months of this deadlock. He did so by having the applications made in

Dublin. `The Hibernian Magazine' for 1778 records `much Quaker solicitation at Court', and as there is no mention of this in the

Society's minute books (in spite of the fact that Friends were very often

active in lobbying members of the Lords and Commons), it must have been done

privately. A letter to Thomas Greer from John Hill, the only trustee from

Lisburn itself and a cousin of Robert Bradshaw, records the fact that John

Hill waited twice on William Higginson after 19th April 1766 and eventually

got another message to the Earl. It was to the effect that the trustees

would soon be in Dublin (almost certainly in order to attend National

Meeting), and to ask whether his Lordship would see them there on 20th May

about the land on Prospect Hill. The noble Earl returned answer that he was

`full and willing' to treat in Dublin or in Lisburn.

The result was that a lease dated 9th June 1766 was signed by the Earl of

Hertford in the presence of three Quakers in Dublin, and by the four

trustees in the presence of William Higginson in Lisburn. Its main provision

was to lease twenty acres of land to the trustees, the lease to be renewed

for ever if, within six years, a schoolhouse was built, hedges and `timber

trees' were planted, and a straight read twenty-one feet wide, with an

additional six feet for ditches, was constructed. The document is long and

detailed, and contains such quaint provisions as the one forbidding trustees

(the Governors of today) to kill, or allow anyone else to kill, hare,

partridge or game on the school lands.

Work on the road began almost at once, as we know from Robert Bradshaw's

report that the labourers could not make a living at the rate they were

being paid, because the soil had proved to be `strong champion clay with

scarce any big stones at all in it'. The men evidently lost much time and

energy in fetching the stones for the road from a greater distance than had

at first been thought necessary -and `the strong champion clay' remained

stubborn until 1964 when the playing fields were re-drained and

reconstructed. However, Robert Bradshaw told the men that the trustees would

take their difficulties `under consideration', and that if their case was

deserving, they would be paid more. `Since then', he wrote to Thomas Greer,

`the work goes on apace'- a testimony to the reputation Quakers had gained

for keeping their promises.

The original 20 acres had been two pieces of land, one in the possession

of James Hunter, not a Friend though connected with the Society, the other

possessed by James Mitchell, about whom nothing is known. At least one of

them was not completely reconciled to the treatment he received, for another

of Robert Bradshaw's reports tells us that in November 1767, just a year

after the labourers threatened to strike, James Hunter and James Hogg made

`encroachments' on the road to the school lands and planned to build

`pillars' to guard what they considered their rightful property. Robert

Bradshaw arranged for the trustees to meet in Lisburn to have the matter

properly adjusted `whereby the infringements of those refractory persons may

be prevented for the future'. In the absence of any evidence to the contrary

we may assume that the trustees were successful.

The First Master, John Gough

With the land secured on the lease for ever and the schoolhouse about to

be built, the trustees next had to find a master. This was very different

from finding a schoolmaster today. For one thing, the universities were not

open to dissenters, so that, in the words of London Yearly Meeting for 1760,

`the number of able and well qualified teachers amongst us is very small'.

In any case, there was at this time a general lack of interest in education

even in the old foundations linked with the established church : the lands

of the Royal School, Dungannon, for example, were being used more for

private profit than for the benefit of its few pupils. And a community which

had small interest in educating its children, paid its schoolmasters very

little. Usually they supplemented a wretched minimum by making a small

profit from boarding pupils and from pursuing a totally different part-time

occupation. The Cork Men's Meeting recorded in 1699, for example, that their

schoolmaster, Edward Borthwick, was neglecting his work by leaving the

management of the school to a boy while he got on with his bookbinding,

often using his press in the schoolroom ; about the same time, Samuel Fuller

in Dublin carried on a business as bookseller and publisher.

Not surprisingly, the trustees looked to England which had provided

Ireland with all her best-known Quaker masters to date - Lawrence Routh to

Mountmellick in 1677, Alexander Seaton (student of Aberdeen University and

admirer of Robert Barclay) to Dublin in 1680, and after him Samuel Forbes,

John Chambers and Thomas Banks. Thomas Greer knew that the task was not easy

for already in 1769 he had tried to find a schoolmaster at the request of

Richard Shackleton of Ballitore. When, therefore, he learned late in 1772

that William Neville was to make `a long tour of England', he asked him to

`make much enquiry about a schoolmaster'. Neville did so, though with little

success, writing to Thomas that he had some names, none of which could be

recommended as `compleat'. It did not seem to matter, he concluded, since 'I

am told thou hast one in view'.

The 'one' in question was John Gough, whose background and credentials

were typical of the Quaker schoolmaster of the time. Born in Kendal,

Westmorland in 1721, he was the second son of John and Mary Gough who

professed "the truth as held by the people called Quakers'. Both boys were

much influenced by their mother. James, nine years older than John,

described her in his Journal as `an industrious, careful, well-minded woman'

who `made it her maxim in her plan of education to accustom her children to

useful employment, frugal fare, and to have their wills crossed'. She sent

them to Thomas Redbank's Quaker school in Stramongate which had been opened

in 1698 (and continued save for a brief closure in 1898 until 1932). They

both proved themselves clever enough to take up schoolmastering, and James

was apprenticed in 1727 to David Hall, the Skipton schoolmaster for whom his

mother had `an honourable esteem'. He was a Quaker of the old sort who would

not allow any other than `plain garb' in his `family', as he called his

pupils and helpers.

John began his schoolmastering with Thomas Bennett of Pickwick,

Wiltshire, but after four years (1736-40) felt a strong desire `to fix his

residence in the same nation' as his brother, and accordingly went to Cork

in the summer of 1740. For the next ten years he followed in James' wake,

first by taking charge of the school at Cork when James was away on Quaker

visits, and then by answering his widowed brother's appeal to join him at

Mountmellick at what had been Thomas Boake's school. Eventually in 1751,

John struck out on his own. In the words of James' Journal

Sometime after this a vacancy falling out in the city of Dublin by the

death of John Beetham Friends' schoolmaster there, and the return of John

Routh (who had tried the place after him) to England, my brother, being

encouraged by friends there to take up the charge of that school, seemed

inclined thereto, and as the prospect seemed promising, I freely assented to

his removal.

The Quaker schoolmaster in Dublin had in the past undertaken certain paid

duties for the Society. They were to `put the proceedings of Yearly_ Meeting

in order' (i.e. record and sometimes compile the minutes) and to prepare

topics of the minutes to send down to provincial Meetings. Until 1747 John

Beetham had done both tasks, at the end of the minutes for which year an

unknown hand recorded `John Beetham deceased'. In May 1748 George Routh of

Marsden, Lancashire came to Dublin and took over these duties at a `sallary

of �40 yearly'. `All Friends', the minute went on,

are desired to use their endeavours to excite Friends who are not members

of this Dublin Monthly Meeting to send their children to this school

The impression of a struggling school is borne out by the brevity of

George Routh's stay, for a minute dated 19th April 1750 announced his

intention of `moving to England'. On 31st May 1750 we learn that John Gough

has been invited to come and has expressed willingness, `provided the school

and clerkship was �60 per annum for the first year'.

With the move to Dublin, where he remained for 23 years, John Gough found

himself at the centre of Quaker activity in Ireland. As Yearly Meeting Clerk

he handled all the Society's main business, and at least twice (in 1770 and

71) attended London Yearly Meeting on behalf of Irish Friends. Further, with

James' removal to Bristol in 1760 he was no longer in the shadow of his

elder and (in Quaker circles) eminent brother. It was his turn to achieve a

modest importance. Yet his long stay in Dublin was not a uniformly settled

one. For one thing, he found it hard to make ends meet. He had married in

1743 Hannah Fisher of Youghal. In twenty years they had fifteen children, of

whom the youngest was five when the family came to Dublin. The salary paid a

schoolmaster would go only part of the way towards providing for so many. It

was supplemented in other ways - by income from a text book, by payment for

Quaker duties, and by Hannah's sale of linen forwarded to her from the

country. Even then, the total income during John Gough's first ten years in

Dublin was small. In addition, John began to feel, like his brother James,

that schoolmastering kept him too much in one place ; he wanted to travel in

the Quaker Ministry (as it was called) and could not. In his own words, lie

felt `fettered' in Dublin, both `in the outward and inward'.

During 1764 there was much talk of his leaving the city. It was the time

of the founding of Edenderry School for girls and a suddenly energetic

Quaker education committee was considering setting up a parallel foundation

for boys. John Gough was mentioned as its possible master. Dublin Friends,

however, wanting to keep John Gough among them, agreed to pay him �20

annually for his Yearly Meeting Clerkship and to `advance' his school income

from �40 to �60 per annum. In return he agreed to stay at least a further

three years. By January 1765 he was writing `. . . we are again settled for

three years longer in this city'. Twelve months after the writing of these

words, and a hundred miles to the north, John Hancock died, and Ulster

Friends set about implementing the terms of his will.

John Gough must have been aware of many of the details of the setting up

of a school at Lisburn, for he was not only Yearly Meeting Clerk, but also

Clerk of the special Schools' Committee set up in Dublin in 1764. Thomas

Greer was usually present at this committee's meetings, the last of which

was held in 1769 by which time the land on Prospect Hill had been bought and

work on the road started. Inevitably, John Gough would know of the search

for a master and of John Nevill's efforts as he journeyed about England ,

inevitably, he thought about his own future. He wanted to move from Dublin.

Was this his opportunity ? Cautiously, and `some time previous' to May 1773,

he hinted to William Nevill - -`but as a matter at a distance' - that

`sooner than the school should fail for want of a Master, he did not know

but he might be inclined to change his sphere of action'. This did not mean,

John Gough said, that the trustees should give up the search for a master

elsewhere ; if that search proved successful, he would `take it as a mark

that Dublin was still his proper place'.

Thomas Greer was not the man to miss such an opportunity. Informed by

William Nevill of the discussion in Dublin, he wrote to John Gough on July

1773 and asked him if he would take charge of the school at Lishurn, if

possible by November. It was more than a fortnight before John replied and

then tentatively. He wanted, he said, `a sense of duty' to be his first

guide, even though he could not, in a world where `human prudence' prompted

most men, altogether ignore practical considerations, especially where the

welfare of his family was concerned. Ile therefore asked two questions :

i) what price `was intended to fix' for boarders and day scholars ? and

ii) what numbers of both `were likely to offer' ?

To leave Dublin, John Gough pointed out, was to `relinquish' �150 per

annum from the school (half a guinea per quarter for each pupil), as well as

the rent of half his house and his payment as clerk of the Yearly Meeting.

On the other hand, a possible advantage of moving would be to free him for

travelling in the Ministry on behalf of Friends, both at home and abroad.

On the back of this letter, Thomas Greer worked a simple sum as follows

This is an estimate of how much is required per pupil from fifteen boys

and fifteen girls if John Gough is to earn the equivalent of his �150 in

Dublin.

By this time the matter was being talked of in the Society. William

Nevill, in the course of a long letter to Thomas Greer, included the

following remarks

There is a possibility that dear James Gough may return to Ireland and

settle in Dublin to fill in part his brother John's place, while John opens

the school at Lisburn and is serviceable in this province.

He added as an afterthought

- if Jonathan Hill should go as his assistant and there fall again in

love with the second daughter and marry her we might have a prospect of a

good schoolmaster and the succession in the right line continued.

Jonathan Hill did come to Lisburn and took charge of the school during

John Gough's absence. He did not marry Mary who in 1778 became Mrs. Mason,

but it is clear that things had been happening in Dublin which had not met

with official Quaker approval. No doubt a good story lies hidden behind this

tantalising glimpse of the past.

Five weeks later, John Gough wrote to Thomas Greer again, this time in

reply to a request for a definite decision one way or the other. He was

still half willing, half afraid to make the change. He expresses `a desire

for the establishment and prosperity of your school'; but from his personal

point of view `it is a very weighty business to think of unsettling himself

at this time of life to remove so far, especially as his present settlement

(in the view of Friends here in Dublin; is not contemptible'. He lists the

main difficulties

The trouble and expense of moving ;

the loss of time and substance between dissolving his school and

establishing a new one ;

and opposition from Dublin Friends.

He agrees, however, to make a firm decision `by eleventh month' (ie.

November 1773). In the meantime, there is no longer need to keep the affair

secret, as `it is taking wind both here and there'.

No further letters on the subject have survived, but we know that John

Gough came to Lisburn in 1774 and remained there for seventeen years, dying

in office in 1791. He was basically, it seems, mild and self-effacing,

although after his move north, he surprised his fellow Quakers (as Richard

Shackleton noted in a letter to Thomas Greer) by his growing confidence and

public presence. Like most Friends of the time, he intoned when speaking to

large numbers of people some Friends, noted the London Quaker journalist

James Jenkins,

thought that what he said was too highly `set to music'-too much of the

harmonious swell -the `concord of sweet sounds', or according to some-the

tuneful note of inspiration.

It was a practice that lingered in Ulster until after 1900, as pupils at

the school have recalled from their memories of Quaker Meetings in the

Province.

There is much evidence that John Gough was an immensely hard worker. He

wrote two text books, an English Grammar (a revision of a work by James, his

brother) of which there is a copy in Friends House, London, and an

Arithmetic which can be seen in the Friends School library. This was used

for decades all over Ireland-the Hedge Schoolmaster, William Carleton, for

example, knew it well. And while at Lisburn he wrote his `History of

Quakerism'. The work of old age and uncompleted at his death, it is, to

quote W. C. Braithwaite, a compilation rather than a piece of original

research, and it draws heavily on Sewel's History. Gough explains that there

have during his time at Lisburn been a number of charges against the Quakers

which need answering. His History is his answer. And he was indefatigable in

attending Meetings in the Province and throughout Ireland. Only a few days

before his death, he was in Dublin ministering at the grave of a departed

Friend.

Throughout his life he was restless. Wherever he went, he once wrote,

`bonds and affilictions' remained with him ; and in the same letter he

complains that he is `as much like to be fettered in Lisburn' as he was in

Dublin. He was perhaps a worrier, and he also had indifferent health-`I

have', he wrote, `for some years been afflicted with a feverish cold'. In

addition, there were difficulties at the school where in the early days he

was `teased with workmen', as his assistant Jonathan Hill put it, more

particularly because there was not `cash to pay the whole'. In January 1776

John Gough had to apply to Thomas Greer to pay a bill of �4 for lime for

school_ house, the bank account being `already in advance', and on a number

of occasions the School Treasurer, Jacob Hancock, the Elder, paid bills with

his own money.

Conditions for Pupils

Interesting as the above facts may be, at least to the historicallyminded,

they tell us almost nothing about the school as experienced by the pupils

from day to day. Yet this is what ultimately matters in any school anywhere.

From 1850 on Friends School, Lisburn, is well supplied with recorded

memories of its scholars, and in later pages these will be allowed to speak

for themselves, but for its earliest days no such impressions have come

down. Even so, it is not difficult to fill in some details. We know, for

example, that John Gough followed brother James in establishing as far as he

could the simple, stern discipline practised by Friends. His Preface to

James' Journal brands as harmful `plays, novels and romances' and wants them

to be replaced by books and ways tending to piety, an attitude that

persisted among many Friends until the end of the nineteenth century. This

Puritan attitude to children had its limitations. Condemning `heathenish

authors' was perhaps understandable, but replacing them by seven books

entitled `Fruits of Early Piety' in which are recorded the last utterances

of those who died young, seems unnecessarily lugubrious -although we do not

know that John Gough used either these books or any of the 3,000 copies of

`The Dying Sayings of Hannah Hill' which Ireland Yearly Meeting had printed

in 1718. Whatever books were used contained no pictures, as pictures were

representations of the truth, not the truth itself (which is why there are

so few portraits of early Friends, who did not approve of them).

John Gough's Preface to the Practical Grammar o f the English Tongue

which, jointly with brother James he produced in 1764, contains some

interesting observations on his methods of teaching. There was, he thought,

a correct order in which knowledge should be presented to children. They

should begin with reading and spelling, geography and history. When enough

progress had been made, the day could be divided between arithmetic and

history or geography, it being always understood that the writing of

epistles (letters) and the study of the scriptures must always continue.

Latin, John Gough thought, was over-valued. `Farewell', he concludes,

and if a better system's thine

Impart it firmly, or make use of mine. |

Of the organisation of the school day we have no direct information about

the Lisburn school, but in that it was very similar to that of other Irish

Quaker schools of the time, it may be assumed to be like that of

Mountmellick. Michael Quane, in an admirable article on this school in the

Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland (Vol. 89 Part I

1959), quotes the following

PLAN OF REGULATIONS FOR SCHOOL

HOURS (1785)

Boys

| hours |

| 6 |

Rise in Summer |

In half hour Roll called in School, Master

reads from the Bible aloud, boys all standing. |

| 7 |

Rise in Winter |

| |

|

Spell from Pennsylvania Spelling Book till |

| 8 |

Breakfast - |

going from the schoolroom to their meals in

good order |

| 9 |

To School. |

Roll called. Writing, Catechism, Arithmetic

till |

| 1 |

Dinner - |

exercise till |

| 3 |

|

called to School, Superintendent hears them

in Catechism. |

| 4 |

Master teaches them Arithmetic - |

examines the work of the day in their

copies and ciphering books - and gives such punishment for faults

committed in the course of the day as his sober judgment determines

adequate thereto - not forgetting to commend |

| 7 |

|

the deserving. |

GIRLS

hours

| 6 |

Rise in Summer |

Every two to make their own bed. Roll

called |

| 7 |

Rise in Winter |

tin an hour or less. Mistress reads, the

girls all standing. The girls appointed for each week then go to sweep

out the room. The rest spell till |

| 8 |

Breakfast - |

In half hour go to school. Master sets them

to write their copies and stays with them till 9 -When they have

finished their copies, Knitting, Sewing, Spinning, etc., till |

| 12 |

|

they use relaxation till |

| 1 |

Dine - |

Mistress after dinner walks them into

garden in dry weather, at which time she has an opportunity of teaching

them to avoid unbecoming awkward gestures. |

| 2 |

to School - |

Master teaching them Arithmetic till |

| 4 |

|

- then rest for an hour. |

| 5 |

|

Mistress instructs them in Reading,

Spelling, Catechism, etc., the remainder of the evening and examines

their work of the day. |

The superintendent, it will be noted, not the master, was responsible for

checking the progress with religious truth, another custom which lasted up

to the present century. The girls spent less time in the classroom than the

boys, using the time thus gained for a variety of domestic tasks. There were

also supplementary orders for the Schoolmaster and Schoolmistress. These

instructed boys to mend their stockings, to go walks with the master and to

do work about the house. Boys in need of correction were to be dealt with

`in the presence of the superintendent'. The schoolmistress had no

instructions about the need for correcting girls although she had to see

that they undertook domestic chores about the house and taught the boys `dearning'.

There were three meals a day : breakfast, dinner and supper. Breakfast

and supper were the same : bread and milk, or potatoes and milk, or porridge

(stirabout). A week of dinners went

| Sunday. |

Bread and broth in Winter ; bread,

potatoes and cheese in Summer. |

| Monday. |

Boiled or roast meat and vegetables for

one table, and pudding or suet dumpling for the other. |

| Tuesday. |

As Monday the other way round. |

| Wednesday. |

Potatoes and either milk or butter. |

| Thursday. |

Meat and Vegetables for both tables in

Winter, Puddings in Summer. |

| Friday. |

Potatoes and milk or butter. |

| Saturday. |

Scraps made out with griskins and the

broth reserved for Sunday. |

| Beer served with each dinner. |

However, the Lisburn school does not seem under John Gough to have been

inspected by Friends appointed by the Quarterly Meeting. The trustees may

have made their own arrangements, but the superintendent, if there was one,

did not report to Ulster Quarterly Meeting whose records are silent on this

score. The report of the Commission of Inquiry into all schools of private

or charitable foundation in Ireland (set up by Grattan's Parliament in 1789,

though not published until 1858) recorded the following

Mr. John Hancock left 1,000 � for the support of a school here, out of

the interest of which being �50 yearly, the annual sum of �25.15/ is paid

for the rent of 20 acres held for ever, for the use of the master, who has

also the remainder of the interest money. A good house built by subscription

among the Quakers. The scolars may be of any persuasion. �50 per annum.

Master - Mr. John Cuff. Total no pupils 52, incl 11 brdrs & 21 day pupils.

No free pupils.

John Gough was taken seriously ill in 1790, recovered partially and

carried on with his work. But, to quote Mary Leadbeater's brief life, `he

was seized with a fit of apoplexy, which in a few hours, ended in his

decease, the 25th day of 10th month, 1791, aged 70'. She goes on, whether

apocryphally or not, who is to know ?

It is remarkable that a short time before his death, being engaged in

prayer, in the meeting to which he immediately belonged, on behalf of the

general state of the church, he was led, by a remarkable transition, to

supplicate for himself, as if sensible of his approaching dissolution.

The words were written some thirty years after his death and bear the

marks of a likely oral tradition.

Again, according to Mary Leadbeater, John Gough `was of a sober,

circumspect life and conversation ... plain and humble in appearance, and

grave in deportment'. It cannot be claimed for him that he was as deeply

original a schoolmaster as his contemporary, David Manson of Belfast. Not

for him the learning games, the Saturday School Parliament, or the ingenious

inventions of Mary Ann McCracken's splendid teacher. But even though David

Manson deservedly became a freeman of Belfast in 1779, his school and

methods died with him in 1792. The grave and stolid John Gough was the first

Headmaster of a school still in being 200 years late.

|