A look at life in the 20th century

A project based on the friendship and work ethnic of

the people in a vibrant community in Ulster.

FOREWORD

The idea for this book was mooted on 17th

March 1998, the day Hillside Terrace, Culcavey, was demolished in

preparation for rebuilding. Whilst surveying the pile of rubble of what

had been a row of mill houses, two people reminisced on the lives of

those people who had occupied the houses, on stories of the area, and

realised how much was being lost and not recorded. This brought about an

article in the Ulster Star and a call for interested parties to meet and

put together information and photographs in order to retain a history of

the Culcavey, Halftown and Lower Maze area. The project was funded by

the Millennium Heritage Fund, to whom we are most deeply grateful. Mr

Bertie Emerson had over a number of years researched and compiled a

history of the area, and with his help and that of Thompson Crossey and

Tom Patterson the idea took shape and has culminated in this

publication.

Many people have helped in the preparation of this book. Local people

have gone out of their way to offer assistance in the search for

information and photographs. Thanks to everyone who contributed.

Thanks must also go to the following people for the contributions they

have made. Mr Peter Ward on the history of LOL 111 and Lower Maze

Scarlet Knights Black Perceptory No.124; Mr Ernie Cromie on Long Kesh

aerodrome; Mr David Adams on the Halftown area; Mr. Thomas Palmer on

family history; Mr. William Finn on the McCandless brothers; Mrs Norma

Higginson on Ogles Grove Farm; Mr Colin Fowler on Culcavey House; Mr CW

Bell on All Saints' Eglantine; Mr Harold McBride on war years in the

Halftown; Mr Herbert Bell and Mrs Annie McClenaghan on Culcavey Factory,

and Mr Derek Henderson and Mrs Barbara Lewers on Newport Primary School.

A special debt of gratitude is due to Mr Brian Mackey who allowed access

to photographs in the Lisburn Museum and kindly gave permission for a

number of them to be reproduced. The Public Record Office of Northern

Ireland also supplied the same service. Thanks also to the Ulster Star

for their help in publicising the search for information.

For his help, guidance and interest, we are deeply indebted to our

editor, Simon Walker, without whose help this book would not have been

possible.

It is inevitable that many stories are missing from this book, and no

doubt in many cupboards and drawers are photographs and documents which

could tell a fuller story. In the future it is hoped to create a museum

in Lower Maze Hall where all photographs included in this book will be

displayed plus the many more which have come to hand.

Pearl Finn & Jackie McQuillan

As It Was

If we were to take a dander down from

Hillsborough to Halftown, a distance of some 2 miles. I wonder how many

of us would notice what has changed over the years. So let's have a go.

We start the journey with the Millvale

Road on our left and what was Smith's garage on the right. Where the Gas

Works stood at the beginning of Millvale Road there now stands a block

of flats. Smith's garage is a motor bike shop. The first field on the

left now accommodates the houses of Hillcourt, whilst directly opposite

on the right the two semi-detached pebble-dashed houses are gone

replaced by red brick apartments. As we head towards the bottom of the

hill we find that on the left-hand side Hillsborough Nursery has gone,

now the Pines. Next to the Nursery was the 'sewage works', and here we

have Harwich Mews. To the right was the entrance to Hillsborough Railway

Station, the site now being a private dwelling. Under what was the

railway bridge, now the bridge accommodating the A1 dual carriageway, we

proceed towards the next small hill, locally known as McBride's Hill.

Before we stretch our legs to ascend the hill we look to the right to

where the lnkpot stood, and to the left the entrance to Culcavey Cottage

Farm (later renamed Culcavey House). Sadly both buildings are gone. When

we reach the brow of the hill Heatherbank Farm was on the lane to the

right. The house still stands, but the farm land around it has been

replaced by modern dwellings.

We proceed on down the road and spot the

entrance on the left to Mill Pond (known locally as the dam or McBride's

dam), a vital element in the power supply to Culcavey Factory in early

days. Here the Pond overflows into the Whiskey River that meanders right

through Culcavey village. Past the Mill Pond stood a two-storey house

and further on Mill Cottage with adjoining building known as the reading

room', all now gone and replaced by a palatial dwelling. Before we

descend the next small hill we look to the right where the large red

brick dwelling known as Ogles Grove House stood and the area around it

which was Bradshaw's Nursery. Both are now gone and where Ogles Grove

House stood we have expensive red brick dwellings. Starting to descend

the hill, if we look to the left where the leafy Culcavey Glen stood we

find once again red brick houses nestled below. If it is quiet we can

still hear the waterfall. At the bottom of the hill Ogles Grove Farm is

on the right, again no longer a working farm, but surrounded by houses.

To the left was the main entrance to Culcavey Factory (Hillsborough

Linen Co.). On entering the main gates on the right hand side stood a

small red brick house, and many will remember it as the residence of

Matt Spence. Adjoining this was a long factory building. All traces of

the factory, house and outbuildings have gone and the whole site is

built up with houses such as Old Mill and Old Mill Heights.

Still standing at the side entrance to

the factory is the old oak tree and where Ogle Terrace begins there were

two small one-storey houses known as Smithy Row. The next row of houses

(still part of Ogle Terrace) was English Row. This is the only row of

the original mill houses left. We pass the entrance to Grove Park, which

used to be an open area leading to the plots' (allotments) which

stretched the back of all the mill houses and were used to grow

vegetables, keep hens and even the odd pig or two. The next two houses

on the left and the shop used to be Shop Row, although there was no gap

between them. The shop is still the original building but the houses

comprising Shop Row have been replaced by Nos. 13 and 14 Ogle Terrace.

On the right-hand side, opposite the shop, was Rose Cottage � a gate

still marks its entrance but the fields are filled with houses.

We now proceed down the hill and on the

left Hillside Terrace (variously known as Grey Row, White Row,

Distillery Row) has been replaced with new red brick houses. At the

crossroads on the road to the left were Thompson's Row and Puddledock

Row. If we proceed over the crossroads, immediately on the right was a

small wooden structure where the children spent their pennies � `Dick's

hut', a small shop run for a long time by the late Mr. Dick Thompson.

Another part of the village missing.

On down the road on the left we have

Oakmount, the residence of the Emerson family. Immediately past their

house was a lane that led to a row of houses known as Railway View.

Something else gone. On the right-hand side was a small whitewashed

cottage, once occupied by the village cobbler. Next on the right is

Culcavey Mission Hall, somewhat changed over the years, but thankfully

still there. The road now diverges slightly, and here we have Newport

Primary School (the new school), the original road now runs down the

back of the school. If we look to the left behind the school we can see

the imposing structure of Newport House, virtually unchanged. On down

the road on the left was the entrance to the coal quays. Small houses

used to stand in this area, some just to the right-hand side as you

entered and some further on down the entrance to the left. The houses

are long gone, the coal quays are gone and more importantly the canal

has gone, replaced by the M 1 motorway. A new more expansive bridge now

replaces the old Newport Bridge that spanned the canal. Also disappeared

from the skyline is the viaduct that spanned the canal, and Newport

railway halt is no more. The road to the right known locally as the

`Dummies Loanin', is now Eglantine Road. Over the bridge we can look to

the left and see the old Newport School. The two roads on the right were

`Berry's Loanin' and `Sandy Lane', while on the left we had `Anthony's

Loanin' and `Moss Road'. Just names in memory now. At Coronation Gardens

we had the entrance to Long Kesh Aerodrome on the left and slightly

further down Lower Maze Orange Hall (now Lower Maze Community Hall).

Such changes: no aerodrome (turned into a prison), and now no prison.

Our next two roads past the defunct prison are Bog Road on the left and

Blaris Road on the right.

From railway, factory, canal and

aerodrome, and everything in between, who notices change?

Where did it all go? Can you remember

spending hours in the glen exploring; jumping across the Whiskey River

to see who could do the biggest jump; walking along the canal tow-path

on a Sunday afternoon; building houses and dens in the hedgerows along

`the plots'; swinging on rope around the lamp-posts; collecting jam jars

and bottles to get your pennies; making a `slide' down the middle of the

road on cold frosty nights; playing football between the gable walls of

Thompson and Puddledock rows; walking to the pictures in Ritchie's Hut

on a Monday night; the hours spent talking at `the corner'; carrying

water from the pump; cooking on the range; coats on the bed in winter;

the dry toilet at the bottom of the garden and `the bucket' under the

bed; `progging' an orchard; `purty hoking'; the tin bath in front of the

fire on a Saturday night; the mangle in the yard; the scrubbing board in

the `jaw-tub'; winding wool off a skein; knitting on four needles and

`turning a heel'; holes in the heels of your socks, and darning?

It seems hard to believe that Culcavey

people of a generation ago simply would not recognise their area.

Nothing remains static in this transitory world.

PLACE NAMES

So much has changed that many of the old

places and their names have now vanished or are unrecognisable. Another

generation or two and this knowledge could be lost forever. Each place,

by its very title, was able to impart something of its tale.

ANNACLOY The fort of the stones.

AUGNNATRISK This means the area of

the brewer's grains.

THE BASIN Near Kesh Bridge was the

'Basin', a large circular area of water three times the width of the

canal, which was the authorised spot for barges to change direction or

to stop and wait to allow oncoming barges to pass.

BLARIS Scottish word for a moor.

BRICKFIELD LODGE This house stood

on the site now occupied by the electricity depot on the Aughnatrisk

Road. Bricks were made from clay here during the seventeenth and

eighteenth centuries.

CULCAVEY The back of the hill of

the lush grass.

DISTILLERY ROW These began life as

sixteen single-storey houses given the name 'White Row' by the linen

company. After the First World War they were given an upper storey and a

coat of grey pebbledash. The company now called the terrace 'Grey Row',

although the directors called it 'Millionaires' Row' as the alterations

had been so costly! Young ladies living in the terrace did not like the

drab new name and so they christened it 'Hillside Terrace'. Although the

houses were demolished and replaced in 1999, thelatter name has been

retained.

EGLANTINE This is a French word

meaning sweet briar or wild rose. It gives its name to the Church of

Ireland parish of All Saints. The Eglantine Road was once known as the

'Dummies Loanin' as an individual who was unable to speak lived there.

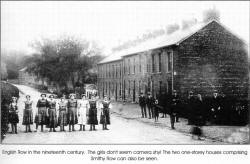

ENGLISH ROW These were eight

two-storey houses. The Englishmen who installed machinery in the linen

factory lived here. This row was originally of red brick, but has been

renovated and is now part of Ogle Terrace. These were built by the linen

company.

HALFTOWN An English translation of

the French word Demiville.

HARRY'S ROAD In the nineteenth

century two brothers lived on this road who kept Harrier hounds for

hunting hares. As a consequence they were, by trade, 'harriers'. The

road was known as Harriers' Road until the brothers died and then the

road became known after the only person living on it, Harry McConville.

KESH BRIDGE This was a hump-backed

bridge and its design was suitable only for slow-moving vehicles.

LAGAN The word 'lagan' is

described as 'Cargo or equipment thrown into the sea from a

ship (in distress), often attached to a float or a buoy to enable it to

be recovered'.

NEWPORT BRIDGE Although there is

still a bridge bearing this name, this dates only from the construction

of the M I motorway. There

were three previous bridges, not on the same site, one of which was a

temporary iron bridge constructed by the army.

PUDDLEDOCK ROAD This led to Puddledock

Farm, where there were deposits of puddle (clay) which, when mixed with

water, made a crude form of cement used to line the walls and floors of

cottages. `Dock' referred to the place where this clay was obtained. The

road is now called the Aughnatrisk Road.

PUDDLEDOCK ROW Named after the road, these were two-storey houses

built by the Hillsborough Linen Company. The row was replaced by Hart

Terrace. SHOP ROW Four

two-storey houses, Culcavey Stores and a dwelling. Although the shop

still stands as a detached building, the other houses were replaced by

part of Ogle Terrace. Built by the Hillsborough Linen Company.

SMITHY ROW This was a one-storey structure � one end a forge, the

other a dwelling. In 1960 four two-storey houses replaced this row and

these are part of Ogle Terrace. `Ogle' is taken from nearby Ogles Grove.

THOMPSON'S ROW Ten two-storey houses named after the builder,

these were also built by the linen company.

OLD CULCAVEY

- HISTORICAL FACTS Until about four hundred

years ago this little corner of county Down was largely uninhabited and

disregarded. When the Normans drove deep into the county in the twelfth

century they established centres of power at Duneight and Dromore. It

was thought that earthen castles or mottes built in those two places

would be sufficient to keep an eye on the residents of the intervening

land. As with most of Ulster until the seventeenth

century, this area would have been heavily wooded, most probably with

deciduous trees. Such means of communication or movement as existed

would have been closely associated with natural physical features such

as rivers or streams. Ulster, like the rest of Ireland, had for

centuries been under the control of the powerful Irish chieftains and

this area fell under the rule of the Magennes clan who lived in a large

`rath' or protected circular farmstead on the present site of

Hillsborough Fort. These clans were troublesome for the English Crown

which, by the sixteenth century, wanted to make Ireland easier to

govern. Under pressure from the Crown, many of the chieftains were

forced to flee from Ireland and the departure of key figures such as

O'Neill and McDonnell is known as the `Flight of the Earls'. With the

native rulers gone, King James I proceeded to implement a scheme to

colonise Ulster with loyal Protestant subjects from England and

Scotland. This grand scheme used the abandoned land of the Irish clans

and was called the Plantation of Ulster. Those who came to Ireland at

this time were called `Planters'. It was the king's

intention that the division of land should be in three tiers:

-

Approved English and Scottish settlers received

about 2,000 acres of land on condition that within three years it

was planted with the aid of forty-eight able-bodied men of their own

nationality. A castle and bawn (walled yard) had to be built to

secure and protect the residents and cattle.

-

Military officers and servitors (ex-servicemen) were

granted 1,500 acres on condition that within two years they built a

strong stone or brick house and bawn. They were permitted to take a

certain proportion of Irish tenants.

-

Native Irish of approved loyalty were granted 1,000

acres on condition that they built a bawn and were permitted to

include some Irish tenants.

These seemingly well-organised divisions were applied in

all of Ulster except Down and Antrim. Here land was granted to or bought

by private individuals who might nowadays be described as entrepreneurs.

However, land was readily available as much had been forfeited to the

Crown or as many of the Irish chieftains seemed willing to sell as their

fortunes now appeared to be on the wane. In county Down alone Brian

McCrory Magennes sold 5,024 acres to an Englishman, Sir Moyses Hill.

With this transaction was born the village of Hillsborough and, as a

consequence, Culcavey. What Sir Moyses found in this area

was not promising. The only settlement was Cromlyn (Irish for the

`crooked glen') � a rather forlorn place, the site of which is in the

grounds of Hillsborough Castle. The hamlet took its name from the little

stream which wound its way through a cluster of tiny mud cabins and past

the ruined chapel of St Malachy. It was to this scene that the Hills

placed their improving hands, creating the places with which we would be

familiar today. By a royal charter of 1660 Cromlyn officially became

known as Hillsborough. Over the next century and a half the village

progressed into an elegant little Georgian town relying on agriculture

and linen. In tandem with this was the development of Culcavey, which

was definitely the industrial jewel in the local crown. Throughout the

development of Hillsborough the guidance and purse of the Marquis of

Downshire was never far away. The same was true for Culcavey. The word

Culcavey has different spellings � Culcavey or Culcavy � but the oldest,

Coolcavey, appears on a map drawn for Lord Hillsborough by Oliver Sloane

in 1745. The earliest indication of commercial industry

is an indenture of lease dated 22nd December 1791 and granted by the

first Lord Downshire (1718-93) to James Henderson, alderman and burgess

of Hillsborough. Mr Henderson was the lessee of Hillsborough Corn Mills,

and the lease allowed him to use the watercourse running to Culcavey

from the dam in Hillsborough Large Park. This corn mill had been built

in the eighteenth century at Millvale and can still be seen as a

residence, along with the former mill manager's house. The mill had a

breast wheel (long since vanished) which harnessed the waterpower. This

watercourse was vital and as it made its way downhill from Hillsborough

it was the life blood for industry at Culcavey. It was to power the

area's linen and distilling industries which gave employment, homes and

prestige to Culcavey over a number of generations.

In the

early years of the nineteenth century Hillsborough and Culcavey must

have been ideal places for those fond of a tipple, for the area boasted

a brewery and a distillery. The brewery was a stone structure opposite

the gates of Hillsborough Parish Church and built in a similar style of

architecture. Its water supply was fed from the lake in the Small Park,

while the stream that ran from the lake fed the distillery at Culcavey. In the

early years of the nineteenth century Hillsborough and Culcavey must

have been ideal places for those fond of a tipple, for the area boasted

a brewery and a distillery. The brewery was a stone structure opposite

the gates of Hillsborough Parish Church and built in a similar style of

architecture. Its water supply was fed from the lake in the Small Park,

while the stream that ran from the lake fed the distillery at Culcavey.

The Hillsborough Distillery, as it was called, was built in 1826 by

Hercules Bradshaw on land leased from Lord Downshire. The granting of

this lease put the marquis in a unique and peculiar position. As a

landlord he could inspect his property whenever he took the notion. This

was not the case with the distillery, as the law stated that the Customs

and Excise officials were the only people with right of entry to a

distillery at any time. Lord Downshire's lease allowed for the supply of

water from the Mill Dam over a weir to Culcavey and "the same shall not

be polluted or injured". At this weir an embankment was built to control

and store water � this was known as the Mill Pond. By 1837 the

distillery had three stills and used 2,000 tonnes of grain per year. A

breast wheel and a twenty horsepower steam engine supplied the power.

The hard-pressed breast wheel was described by locals as 'rowdy'! The

supplies of grain and coal reached the distillery from the Lagan Canal

at Newport.

In addition to the serious commercial

business of distilling we can add a touch of humour by recording the

circumstances under which the Whiskey River acquired its name. It seems

that the distillery had a small customs office between the distillery

building and Mill Pond. The distillery officials discovered that

they had more hogsheads of whiskey in their possession than appeared in

the records. No-one could account how the surplus stock came about, but

through the `grapevine' it became known that the customs men were coming

to inspect the stock. To rectify this state of affairs the workers

pulled the bungs out of the barrels and so the precious liquid flowed

down the river. The villagers came to the riverside with buckets, baths,

crocks or anything that would hold water, and thus they collected the

whiskey. It is said that many locals were drunk for weeks! From that day

onwards the waterway was called the Whiskey River. The

original proprietor of the distillery, Mr Bradshaw, must have been a man

of means, for in 1826 he was able to build himself an ornate house known

as Culcavey Cottage Farm. He demolished an existing property and

constructed a fine house surmounted by a dome situated in landscaped

grounds of one hundred acres. The original entrance was from the

Millvale Road which led along a tree-lined avenue called Green Lane.

From this ran a cobbled road leading to Kennel Hill; so-called due to

the breeding of dogs which took place there. From the vantage point of

his domed house, Mr Bradshaw could watch the Maze races with his

telescope. He seems to have been greatly interested in all things

scientific and was an early exponent of the infant photography industry

� so much so that he owned an early camera obscura. The

brewery in the main street of Hillsborough disappeared some time

probably between 1856 and 1868, and so it is perhaps related that

whiskey distilling at Culcavey ended in 1865. This must, at first, have

seemed like devastating news for the employees and residents of Culcavey

who relied on the distillery for their livelihoods. This must not have

been good news either for those who enjoyed sampling the home grown

produce. However, the commerce of the area was saved when the distillery

premises were taken over by the Hillsborough Woollen Company in 1866.

The company enjoyed a brief `honeymoon' period, before experiencing the

effects of the monopoly of the Yorkshire Woollen Merchants. Given that

county Down was famous for its linen trade, wool could really not

compete, and by 1871 the company began trading as the Hillsborough Linen

Company. As with previous industries on the site, the linen mill relied

on its water supply. Water came from the Mill Pond via sluice gates into

the Mill Race which fed into two large brick tanks sunk into the side of

Culcavey Glen. These were deep and dangerous and occasioned a terrible

tragedy in the 1890s when a young boy lost his life by falling into

them. It was seven days before his body was recovered. This unhappy

episode earned the tanks a nickname � `the coffins'.

Close to the tanks stood the tall brick factory chimney, which spewed

out great clouds of smoke as the fires below created steam to drive the

machinery. Four dams supplied the giant amounts of water needed. The

steam created was used for cleaning, bleaching and heating. It was also

needed to maintain humidity in the weaving sheds where the looms

constantly thundered away creating linen goods that would travel to the

corners of the British Empire. Grey yarn was purchased in hanks and

stored in the old malting lofts until required. It was then bleached,

dried, wound and warped. Finally it was woven into cloth. The types of

cloth woven ranged from damask rose to towelling and more looms had to

be built to meet the demands for these products. Power

from the steam engine was transmitted by a main shaft, cog wheel and

bevel shaft. The looms were all driven by overhead shafts, which were

manufactured by Atherton Brothers of Preston. To maintain production on

this scale, tonnes of coal were required and it was transported via the

Lagan Navigation Canal at Newport Quay. These laborious processes ended

in 1961 when mains electricity was installed. The lapping

room was a substantial three-storey building with a slated roof and it

was here that the cloth was `lapped' until 1908. In this year the

process moved to Belfast due to shortage of labour and the process was

conducted in a warehouse in Bedford Street, which was owned by the

Hillsborough Linen Company. The linen cloth was taken from the factory

by horse and flat four-wheeler van. This horse was called Mr Todd after

a former manager of the factory. The warehouse remained in operation in

Bedford Street until 1960 when traffic congestion and high costs forced

the lapping to be recommenced in Culcavey.

With the

constant roar of activity at the mill and the heavy work and calls of

the bargemen on the canal, Culcavey must have seemed an industrious and

restless place. In 1863 the Lisburn to Banbridge railway line encroached

on the scene, halting at Hillsborough Station. The railway now made the

transportation of goods to and from the factory more convenient, but was

a blow to the canal. The main line from Belfast passed through Knockmore

and the length of the section from here to the level crossing on the

Millvale Road was less than three miles. It was necessary to build road,

river and rail bridges and three level crossings to accommodate the

track. The level crossings were at Ogles Grove, Heatherbank and Millvale

Road. After crossing the river Lagan there was the ten-mile post from

Belfast. With the difference between the flat land at the Lagan and the

highest point at Magherabeg, en route to Dromore, the engineers had

calculated a gradual gradient for this stretch of track. With the

constant roar of activity at the mill and the heavy work and calls of

the bargemen on the canal, Culcavey must have seemed an industrious and

restless place. In 1863 the Lisburn to Banbridge railway line encroached

on the scene, halting at Hillsborough Station. The railway now made the

transportation of goods to and from the factory more convenient, but was

a blow to the canal. The main line from Belfast passed through Knockmore

and the length of the section from here to the level crossing on the

Millvale Road was less than three miles. It was necessary to build road,

river and rail bridges and three level crossings to accommodate the

track. The level crossings were at Ogles Grove, Heatherbank and Millvale

Road. After crossing the river Lagan there was the ten-mile post from

Belfast. With the difference between the flat land at the Lagan and the

highest point at Magherabeg, en route to Dromore, the engineers had

calculated a gradual gradient for this stretch of track.

Hillsborough Station was built on the side of a small hillock on the

Culcavey Road and was a red brick two-storey structure. As well as the

The railway viaduct at Newport ticket office there were waiting and

storage rooms and living quarters for the stationmaster. The social

impact of the railway made journeys to Belfast much easier and more

comfortable than before, although the round trip still took the

traveller a whole day. During the two world wars the railway proved its

worth with a specially constructed halt at Newport to facilitate service

personnel stationed at nearby Long Kesh. The tracks passed over two

notable local bridges called `The Viaduct' and Greer's Bridge'. The

viaduct was a lattice-type bridge which spanned the canal and Dummies

Road. Greer's Bridge was situated at the entrance to Eglantine Cottage

Farm. The locals never used the official names for these structures and

called one `the railway bridge' and the other `the railway arch' or `the

arch'.

Changing social and economic conditions brought

about the closure of this branch line in 1956. The track, bridges and

station were sold and the land offered for sale to the holders of the

original deeds. Remnants of Greer's Bridge and the embankment can still

be seen. The station itself was occupied by a number of tenants,

including Mr Thompson Crossey who operated a scrap business from it.

Sadly, the building has now gone altogether, although a glimpse of the

old railway station at Dromore will give an idea of what Hillsborough

Station looked like as, presumably, they must have been designed by the

same architect.

By the beginning of the twentieth century

Culcavey was a thriving place where the majority of people had

employment. However, life was hard and made great demands on the

inhabitants, whose lives generally followed a pattern of work, sleep and

worship. The pattern of life was well established and appeared destined

to continue like this forever, but the twentieth century, especially its

latter years, was to witness dramatic social changes in the district.

No-one could have guessed the importance the place would serve in

determining the outcome of the Second World War, or that this importance

would have been underscored by visits from people as distinguished as

General Eisenhower, King George VI and Field Marshal Montgomery. During

the war the British government was fearful that Hitler's Germany would

use the Republic of Ireland as a back door into Britain as a means of

invasion. The British would, therefore, need to respond quickly using

the air force. And so it was that RAF Long Kesh was set up, along with

bases at Sydenham, Maghaberry and Blaris. Building work at Long Kesh

commenced in November 1940 and culminated in the opening of an airfield

in November 1941. By 1942 the threat of a German invasion of Britain had

receded and a new role was found for RAF Long Kesh. On 1st April 1942

the United States navy commenced a thrice-weekly service between

Eglinton and Hendon (London) airfields, calling at Long Kesh. By the end

of the war the base was used to instruct pilots and crews in the

operation of Beaufort and Hampden aircraft. Throughout the war period

the base saw a succession of aeroplane types which became increasingly

advanced, particularly as US involvement in the war deepened. In the

summer of 1945, and against a backdrop of victory, the base received

visits from senior personages involved in co-ordinating the war. General Eisenhower, King George VI and Field Marshal Montgomery. During

the war the British government was fearful that Hitler's Germany would

use the Republic of Ireland as a back door into Britain as a means of

invasion. The British would, therefore, need to respond quickly using

the air force. And so it was that RAF Long Kesh was set up, along with

bases at Sydenham, Maghaberry and Blaris. Building work at Long Kesh

commenced in November 1940 and culminated in the opening of an airfield

in November 1941. By 1942 the threat of a German invasion of Britain had

receded and a new role was found for RAF Long Kesh. On 1st April 1942

the United States navy commenced a thrice-weekly service between

Eglinton and Hendon (London) airfields, calling at Long Kesh. By the end

of the war the base was used to instruct pilots and crews in the

operation of Beaufort and Hampden aircraft. Throughout the war period

the base saw a succession of aeroplane types which became increasingly

advanced, particularly as US involvement in the war deepened. In the

summer of 1945, and against a backdrop of victory, the base received

visits from senior personages involved in co-ordinating the war.

The post-war years saw living standards improve generally and with

consequent developments in technology, and the effects on all aspects of

life, it was inevitable that a little place like Culcavey would

experience change. Consumers became more demanding and expected access

to all the new goods and materials on offer. The world was moving into

an age of synthetic and disposable goods. This applied to the material

which for generations had provided the backbone of life in Culcavey �

linen. The linen industry was severely affected by the production of new

fabrics and fabric mixtures and it was obvious that it could not

compete. In 1966 the din of the weaving shed was stilled and the looms

ceased their labour of more than a century. The Hillsborough Linen

Company closed its premises, cutting in the process the threads of

employment and skill which had long bound the community together. It was

left to the inhabitants of the district to create a new identity and

this they did against a background of enormous physical changes in the

area. With the end of the linen industry the district initially lost

some of the vibrancy which the factory had leant it, and by the 1970s

the number of pupils at Newport Primary School indicated that Culcavey

was experiencing a decline in its population. This was to be

short-lived, as the area soon found itself caught up in the swath of

residential development that has so dramatically changed much of

Northern Ireland. The post-war years saw living standards improve generally and with

consequent developments in technology, and the effects on all aspects of

life, it was inevitable that a little place like Culcavey would

experience change. Consumers became more demanding and expected access

to all the new goods and materials on offer. The world was moving into

an age of synthetic and disposable goods. This applied to the material

which for generations had provided the backbone of life in Culcavey �

linen. The linen industry was severely affected by the production of new

fabrics and fabric mixtures and it was obvious that it could not

compete. In 1966 the din of the weaving shed was stilled and the looms

ceased their labour of more than a century. The Hillsborough Linen

Company closed its premises, cutting in the process the threads of

employment and skill which had long bound the community together. It was

left to the inhabitants of the district to create a new identity and

this they did against a background of enormous physical changes in the

area. With the end of the linen industry the district initially lost

some of the vibrancy which the factory had leant it, and by the 1970s

the number of pupils at Newport Primary School indicated that Culcavey

was experiencing a decline in its population. This was to be

short-lived, as the area soon found itself caught up in the swath of

residential development that has so dramatically changed much of

Northern Ireland. In the period since the 1970s the

district, once known for its linen manufacture, became known for very

different reasons. With the onset of the `Troubles' in 1970, the Long

Kesh base was brought back into service as a prison to detain those held

under Brian Faulkner's policy of internment. This ensured that the Maze

was never far from the public gaze. The eyes of the world were turned on

the area in 1980and 1981 during the tense period of the hunger strikes

by republican prisoners in the `H-blocks'. The Maze Prison again came to

prominence during and after the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, which

instigated the prisoner release programme. Due to this the prison closed

in 2000, once again creating the potential for change.

People often fear change and this is understandable when the change is

rapid. The visitor of today would hardly recognise the Culcavey,

Halftown or Maze of thirty years ago. The mill, for so long the focal

point of the area, has gone. Indeed, even its buildings have gone, being

demolished to make way for houses in 1993. The proximity of the district

to Hillsborough accounts for its popularity for housing, but few would

probably appreciate the very independent development the area has had

over many generations and that the names of new developments, such as

`Old Mill Heights', recall that heritage. This book does that through

the eyes of those who have lived through these changes.

A

CHANGING SCENE

The two mile journey from Hillsborough to Halftown would be just 'a nice

stretch of the legs', but makes an interesting excursion to the

perceiving eye if we can go back in time and remember how it used to be.

HILLSBOROUGH NURSERY

Situated on the left-hand side at the bottom of the hill on the Culcavey

Road out of Hillsborough just before the railway station, the Nursery

ran from the Culcavey Road to the Millvale Road. Mr & Mrs Bob Bell, the

owners, lived in a house on the Millvale Road and the Nursery was really

their large, expansive back garden. Row upon row of greenhouses nestled

in the hollow. The soil was fertile and lush and the Bell's knew their

job and their market. Mr Tom McQuade was their foreman and lorry driver,

overseeing the workers and taking the produce to shops and markets.

Young and old were employed here, and if you were a good worker you were

welcome. Here was the nursery business at its best, all the age-old

methods employed in producing first-class plants. These nurserymen knew

their skills and there were no short cuts in those days.

When Mr & Mrs Bell retired Tom McQuade took over the Nursery for a good

number of years until he too retired. Now all we have in its place are

red brick houses that extend right to the Millvale Road.

THE RAILWAY

The railway arrived in this area on 13 July 1863 with the opening of the

Banbridge, Lisburn and Belfast Railway. The line was later taken over by

the Ulster Railway and eventually became part of the Great Northern

Railway. The construction of the railway had been an enormous

undertaking and it had cut its way through the countryside of county

Down. And it has left its mark - most notably in the magnificent viaduct

at Dromore. The railway arrived in this area on 13 July 1863 with the opening of the

Banbridge, Lisburn and Belfast Railway. The line was later taken over by

the Ulster Railway and eventually became part of the Great Northern

Railway. The construction of the railway had been an enormous

undertaking and it had cut its way through the countryside of county

Down. And it has left its mark - most notably in the magnificent viaduct

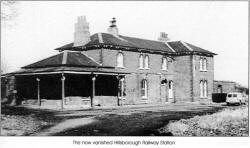

at Dromore. Hillsborough Station was situated on the

Culcavey Road and was a building typical of the time - two-storey, red

brick with arched windows and ornate over-hanging eaves. All was

contained under one roof, from the ticket office to the Stationmaster's

house. A siding and goods shed catered for all kinds of merchandise and

there were pens to assist with the movement of livestock. Not only did

the trains make travel more convenient, but the strict adherence to

time-keeping meant that the locals could tell the time of day by the

punctual appearance of a train. The canal was crossed by an iron

lattice-work viaduct supported on stone piers.

During the

Second World War the threat of air raids meant that valuable goods were

dispersed throughout the countryside and many goods trains carried loads

to Hillsborough Station under the cover of darkness. To keep this

section of line in good order a team of men carried out regular safety

and maintenance work. A workman carrying a wrench-cum-hammer over his

shoulder carried out the inspection, checking and tightening each nut on

the line. During the

Second World War the threat of air raids meant that valuable goods were

dispersed throughout the countryside and many goods trains carried loads

to Hillsborough Station under the cover of darkness. To keep this

section of line in good order a team of men carried out regular safety

and maintenance work. A workman carrying a wrench-cum-hammer over his

shoulder carried out the inspection, checking and tightening each nut on

the line. Just as the railway had robbed the canal of

much of its business, so the advent of the motorcar deprived the railway

of its custom, and the branch line closed in 1956. The monuments to the

Victorian engineers - the bridges, the embankments and the great steam

engines- all disappeared from the scene. Even the railway station has

now vanished, having survived for a while as the premises of a scrap

business. However, the railway is not forgotten, for it is still common

to hear older residents refer to the Railway Road, before correcting

themselves and saying Culcavey Road.

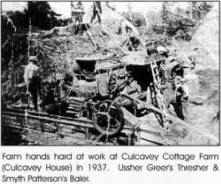

CULCAVEY COTTAGE FARM (LATER CULCAVEY HOUSE)

As you pass under the bridge spanning the A1 dual carriageway, and what

was once the railway bridge, the first hill you see in the distance is

locally called McBride's Hill. Before you traverse this hill the lane

way on the left-hand side was the original entrance to Culcavey Cottage

Farm (later Culcavey House), built in 1826 by Mr Hercules Bradshaw, the

original proprietor of Culcavey Distillery. (It should be noted that a

'Culcavey House' existed long before Mr Bradshaw's dwelling was

constructed, but on an entirely different site - as will be seen from

later information in this book.) For those who can remember this ornate

residence of Mr Bradshaw, the one thing that stands out in recollection

is the large dome that graced the top of the house and gave an

outstanding view of the surrounding countryside. But for many this was

the only thing they saw of the house set in its own extensive grounds. As you pass under the bridge spanning the A1 dual carriageway, and what

was once the railway bridge, the first hill you see in the distance is

locally called McBride's Hill. Before you traverse this hill the lane

way on the left-hand side was the original entrance to Culcavey Cottage

Farm (later Culcavey House), built in 1826 by Mr Hercules Bradshaw, the

original proprietor of Culcavey Distillery. (It should be noted that a

'Culcavey House' existed long before Mr Bradshaw's dwelling was

constructed, but on an entirely different site - as will be seen from

later information in this book.) For those who can remember this ornate

residence of Mr Bradshaw, the one thing that stands out in recollection

is the large dome that graced the top of the house and gave an

outstanding view of the surrounding countryside. But for many this was

the only thing they saw of the house set in its own extensive grounds.

The house for a good number of years was the home of the McBride family,

who still reside in the area, and in latter years was known locally as

McBride's House. Colin Fowler's father Bertie, whose mother was a

McBride, was born in this house, and in later years when its grandeur

was in decline Colin himself resided there for a few years. His

description of the inside gives an insight into the size and

magnificence of this gentleman's residence. The avenue

to the house was lined at that time with many beautiful trees, yew,

golden cypress and juniper, with one magnificent cedar reputed to be the

largest in Britain. The house itself was a

splendid building with many rooms and servants' quarters, these being

connected to the rest of the house by a system of signal bells operated

by hand pulls and linked together by wires. The ground floor had many

fine rooms fitted with Italian marble fireplaces and with french-windows

opening directly onto well-kept lawns. These rooms included a grand

ballroom with parquet flooring and a very large dining room paved with

sandstone flags. A most unusual feature of the

upper storeys was a winding staircase leading to a glass dome towering

above all the rooftops. It was said that from this vantage point the

Maze races could be watched through spyglasses.

The McBride family in those days would have probably been considered as

landed gentry. Their mode of transport was by carriage and they had many

stables and horses with their own blacksmith's shop. They also had boats

on the lake below the house, and this lake they had stocked with rainbow

trout as most of the family were keen fishermen. The large estate

included separate housing for several .families' employed on the land,

and there so far as we can tell they all worked happily and harmoniously

together. This of course was in the good old days when farming was still

a gainful occupation. It was rumoured that the

house contained a secret escape tunnel or bolt-hole, but this was so

well hidden that it could never be found. Many old

houses have supernatural stories attached to them, and Culcavey House

was no exception with tales of dreadful apparitions floating several

feet above the ground being seen on certain nights. Then too the

headless horseman who still managed to utter a horrid laugh, and other

things unseen with much clanking of chains and rattling of bones!

Now that the old mansion has alas long gone these phantoms have most

likely all retired on good pensions!

THE INKPOT

Opposite the entrance to Culcavey Cottage Farm (later Culcavey House)

stood the Inkpot. This was a small house and so-called because of its

appearance with a chimney at the summit of a four-sided roof. The

cottage was a square, measuring 25 feet by 25 feet. The occupant was

responsible for opening and closing the entrance gates to Cottage Farm.

HEATHERBANK FARM

Situated on the right-hand side at the brow of what is locally called

McBride's Hill was Heatherbank Farm. This two-storey house was

surrounded by fields and adjacent to the railway. Here was a railway

crossing known as `Heatherbank Crossing'. Edwin George Sands and his

wife Sarah occupied the house at one time. Edwin Sands was born in 1853

and died in 1925, whilst his wife was born in 1859 and died in 1935.

(The Sands family is mentioned later in this book in connection with

farming.) They sold the property to a Mr & Mrs William Flynn. In later

years it was the home of Situated on the right-hand side at the brow of what is locally called

McBride's Hill was Heatherbank Farm. This two-storey house was

surrounded by fields and adjacent to the railway. Here was a railway

crossing known as `Heatherbank Crossing'. Edwin George Sands and his

wife Sarah occupied the house at one time. Edwin Sands was born in 1853

and died in 1925, whilst his wife was born in 1859 and died in 1935.

(The Sands family is mentioned later in this book in connection with

farming.) They sold the property to a Mr & Mrs William Flynn. In later

years it was the home of

Mr & Mrs Hamilton Bell. Mr Bell operated a Saw Mill here for cutting

trees into planks. The house still remains but the farmland around it

has been developed into private housing.

MILL POND

To the people of Culcavey Village `Mill Pond' was commonly referred to

as `the dam' or 'McBride's dam'. The water from Mill Pond, via the

sluice gates, entered the Mill Race situated on elevated ground on the

west side of Culcavey Glen. The Mill Race flowed onwards into two large

brick built tanks sunk into the side of the Glen. Here was the source of

power to generate the Linen Mill. The overflow from the Pond traversed

down the Whiskey River. To the people of Culcavey Village `Mill Pond' was commonly referred to

as `the dam' or 'McBride's dam'. The water from Mill Pond, via the

sluice gates, entered the Mill Race situated on elevated ground on the

west side of Culcavey Glen. The Mill Race flowed onwards into two large

brick built tanks sunk into the side of the Glen. Here was the source of

power to generate the Linen Mill. The overflow from the Pond traversed

down the Whiskey River.

In early years the Mill Pond

contained many species of fish found in fresh water ponds. The arrival

of eels via Lough Neagh and the Canal put paid to the fish. For those

who can remember the eels were extremely large, silvery and

slippery. Perhaps to generations of children the dam was

a place where you could wander round in search of birds' nests, try to

catch fish or eels, or even at the shallow edges sit on a grass bank and

paddle your feet. Today it is a haven for the many ducks and swans who

feed uninhibited. BRADSHAW'S NURSERY

On the opposite side of the road to the entrance of Mill Pond was

Bradshaw's Nursery. The Nursery extended as far as Culcavey crossroads

and in its time must have been one of the largest in the Province. Local

information states "that over 100 men were normally employed here, and

extra `hands' were taken on in the height of the season". The area was

originally known as `Ogles Grove', but employees called it Bradshaw's

Nursery because the Marquis of Downshire's gardener, Mr Bradshaw

supervised it. Mr Lennox Davis succeeded Mr Bradshaw. Thorn quicks,

decorative hedges, shrubs and trees were propagated, cultivated and

despatched from the Nursery. The Nursery was still in operation in 1931

when Mr Arthur Walker (father of Stewarty Walker), who was head

gardener, died whilst conducting business at Belfast Market.

The following part of a poem, whose author is unknown, is a reminder of

the above era: Ogles Grove �

The Seat of Henry Davis, 1834 As o'er the plain

my ramblings I pursue

An Ancient spot burst forth upon my view.

Neat handsome plantings on each side arise,

Here blooms the pride of modern nurseries.

What wonderful taste! It seems the bower of love.

Oh! Let me breathe the air of Ogles Grove.

Who has not felt in such a scene as this

The thrilling joy of summer's evening kiss?

His spirit dancing, while the hum of bees

Rose on the pinions of the sconce-felt breeze.

OGLES GROVE HOUSE

This tall imposing red brick residence was situated up a long lane-way

on the right-hand side of the road just past Mill Pond. It was the

original residence of the Pimm family. The Pimm family sold the house to

Mr Marshall, a Miller of Victoria Street Belfast. Mr & Mrs Parks were

the next owners, Mrs Parks being a member of the Cowdy family from

Banbridge who owned the Linen Mill, and Mr Parks a retired Army Colonel.

Finally the last owners of this lovely house were Mr & Mrs Boyd. Mr.

Boyd was a bank official for the Ulster Bank. Sadly the house was

demolished a few years ago and the grounds are filled with new modern

dwellings.

MILL HOUSE AND MILL

COTTAGE (or Glen Cottage)

Almost opposite the entrance to Ogles Grove House stood Mill House, a

two-storey dwelling owned by the Mill and a `tied house', one had to

work in the factory to occupy it. As the nearest house to Mill Pond

(dam) the tenant was responsible for opening the sluice gates each

morning to generate the power for the Linen Mill, and perform the

opposite function at night when power went off at 10.00 p.m.

Mill Cottage (or Glen Cottage) stood slightly further down at the top of

what was known as the Factory Hill. This would originally have been the

Customs House. Although a two-storey structure, from the front one would

expect it to be one-storey, as it was in fact built into a hill. Three

bedrooms merged off the hallway at the front door. You went down a few

steps and a small box room was on your right, the door on the left led

down another few steps into a large kitchen (living room). Running off

this large room was a scullery (kitchen) and another room used as a

store room. There was a fire in one of the bedrooms and a large range in

the kitchen. Water was carried from the tap just inside the Mill gates

at the bottom of the hill. Electric light was generated from the Mill,

with the exception of the bedroom on the right-hand side, which for some

reason had no access to lighting. Joining onto Mill Cottage was another

building known as `the Reading Room'. Its purpose must have something to

do with work in the Mill. A dry toilet was outside, situated on a steep

bank almost overlooking the waterfall in the glen. A pathway led

directly from the house down to the Whiskey River. The gardens were

extensive, the front garden ablaze with flowers and a rose arch at the

front door. The back garden held a good chicken run and lots of space

for cultivating.

The photograph opposite, taken between

1910-1912 shows the Smyth Family at Glen Cottage. Sitting from left to

right, William John Smyth and his wife Sophia, Henry Smyth and his wife

(parents of William John). Standing left to right the children are,

Dorothy, Madge, Sophia, Hennie and Minnie with Winnie sitting on

mother's knee. Henry Smyth was Assistant Manager of Culcavey Linen Mill

and William John was Winding Master. The rest of the family all worked

in the Mill at various jobs. The photograph opposite, taken between

1910-1912 shows the Smyth Family at Glen Cottage. Sitting from left to

right, William John Smyth and his wife Sophia, Henry Smyth and his wife

(parents of William John). Standing left to right the children are,

Dorothy, Madge, Sophia, Hennie and Minnie with Winnie sitting on

mother's knee. Henry Smyth was Assistant Manager of Culcavey Linen Mill

and William John was Winding Master. The rest of the family all worked

in the Mill at various jobs. The family suffered

tragically while living here. Henry Harry Smyth, son of William and

Sophia, born on 20th April 1911 was drowned at the back of the house in

the Whiskey River on 15th March 1914. The postman accidentally left the

side gate open and the lure of the water proved tragic, his body was

found further down the river at the Linen Mill. The family moved from

the Glen and took up residence at No. 15 Grey Row which at that time was

quite an expansive house, occupying the whole corner site. Part of No.

15 was later annexed to provide a smaller dwelling for the Factory

Manager's housekeeper. The bigger house provided ample space for this

large family: Minnie (born 12th July 1899), Dorothy (born 5th February

1902), Madge (born 20th March 1904), Hennie (born 16th November 1905),

Sophia (born 17th April 1907), Winnie (born 10th August 1909), Florrie

(born 20th December 1913), Ethel (born 4th March 1918) and Harold (born

2nd March 1920). Colin Lillie from Hillsborough, whose

mother was Dorothy Smyth, recalls vividly his mother's recollections of

life at Glen Cottage, and how she left the house at Grey Row to get

married. His grandmother, Sophia, never really got over the death of her

young son and died at the early age of 43. THE GLEN

Culcavey Glen nestled between Culcavey Road, the Mill Pond, Mill Race

and the Factory, and for the people of the village it was a magical

place. The Whiskey River meandered from the Mill Pond (dam) down through

the Glen and via the Mill continued on down the back of the houses in

the village. To remember the Glen is to think of quietness in its leafy

depths, the birds singing, sound of the waterfall cascading down the

rocks. Carpets of bluebells grew in the dappled shade, primroses peeped

from the edges of the river. There was an assortment of broad-leafed

trees, tall ferns, brambles and bushes. For children it was an enchanted

world to explore, things to be done and found in all seasons � looking

for birds nests, home-made swings on the trees, climbing the almost

mountain-like banks up onto the Culcavey Road, looking for chestnuts in

the autumn and blackberries in the summer. To remember, just close your

eyes and think back to the tall trees rustling above you, the peace and

quiet and no background noise of traffic or modern day life. It was a

timeless

place, taken for granted and only really appreciated

when it had disappeared.

THE MILL � HILLSBOROUGH LINEN COMPANY

Although we have already said something of the history and importance of

the mill, it is interesting to read what Bassett's County Down Guide and

Directory had to say about the factory in 1886.

The Hillsborough Linen Company, Limited

The factory of the Hillsborough Linen Company, Limited, is situated

at a distance of about a mile, English, west of Hillsborough, and less

than hall a mile from the railway station. Buildings, three storeys and

two storeys high, cover about two acres, and on 26 acres there are 52

workmen's houses. Altogether, the premises consist of about 140 statute

acres, including a grazing farm. There are 318 looms, with the latest

improvements. The manufactures include towellings, diapers and damasks.

Yarns spun from Irish and Belgian flax are chiefly used. The products

are sent to the markets of the United Kingdom and to the United States

and Canada. An engine 135 horse-power, drives the machinery in summer.

In winter a turbine wheel, equal to 70 horsed-power, is used as an

auxiliary. The factory of the Hillsborough Linen Company, Limited, is situated

at a distance of about a mile, English, west of Hillsborough, and less

than hall a mile from the railway station. Buildings, three storeys and

two storeys high, cover about two acres, and on 26 acres there are 52

workmen's houses. Altogether, the premises consist of about 140 statute

acres, including a grazing farm. There are 318 looms, with the latest

improvements. The manufactures include towellings, diapers and damasks.

Yarns spun from Irish and Belgian flax are chiefly used. The products

are sent to the markets of the United Kingdom and to the United States

and Canada. An engine 135 horse-power, drives the machinery in summer.

In winter a turbine wheel, equal to 70 horsed-power, is used as an

auxiliary. The buildings belonging to the

Hillsborough Linen Company Limited originally served the purposes of a

distillery, operated until the time of his death, about twenty years

ago, by Mr. Hercules Bradshaw; a celebrated man of the turf and the

owner of Barbarian, once a favourite for the Derby. A short time after

the demise of Mr. Bradshaw the distillery was acquired by a Limited

Liability Company and changed into a woollen factory.

A second limited liability company was formed while the concern was

in full operation. It bought out the first company and continued to work

until 1876, when a change was made .from woollens to linens, the company

re-organised and its name altered to the Hillsborough Linen Company,

Limited. Some of the shareholders of the first company have stock in the

present successful enterprise. Mr J.J. Pimm of

Lisburn, is managing director, and Mr. Arthur Pimm secretary. Mr Arthur

Pimm resides at Culcavy Cottage, in handsomely planted grounds. About

300 people are employed in the factory, of this number more than half

are females. At the entrance to the factory there

is a school under the National Board of Education. It is chiefly

attended by children of the company's operatives. The first storey of

the school-house serves as a reading and recreation room. It was

established by the company for the workmen, who manage it by committee.

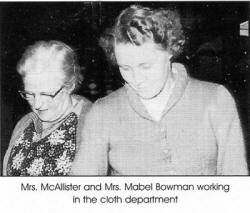

for their own benefit. MILL PEOPLE

For generations the mill provided the means of existence for a large

proportion of the local population and this was often readily

acknowledged. The Ulster Star of 9th November 1957 produced an article

on the work of the Hillsborough Linen company. This article has been

used to piece together information about the mill workers. For generations the mill provided the means of existence for a large

proportion of the local population and this was often readily

acknowledged. The Ulster Star of 9th November 1957 produced an article

on the work of the Hillsborough Linen company. This article has been

used to piece together information about the mill workers.

The Star noted that, in 1957, Andrew Armstrong had just replaced James

McCandless as factory manager, while Robert Wilkinson was the assistant

manager. Many of the employees had worked in the mill all their adult

lives, one such person being Agnes Kane, who worked in the warp winding

section for over sixty years. Matt Spence, a tenter, worked in the

factory for over forty years. Warren McCleary was the father of Ernie

McCleary, the Cliftonville footballer and Irish Amateur International.

The article went into a great deal of detail and mentioned the names of

people long-associated with the factory: Boreland; Bowman; Bryans;

Cairns; Copeland; Hewitt; Harris; Hull; Kane; Ringland; Pollock; Spratt;

Walker; McAllister. It is interesting to note that the

Star went to great pains not to divulge any of the mill's trade secrets

� they obviously didn't want to help the competition!

Herbert Bell of Tullynore, Hillsborough, had his own recollections of

many of these people and their work: I went to work in

Culcavey Factory in 1931/32. I was learning weaving. for a short period,

then working at bleaching yarn, and later I was operating a cropping

machine in the cloth office. The older person on the large machine was

George Cunningham; he was reared at Chimney Hall, Lisburn Road. The

cloth inspector was Waring McCleery .from Moira, and he was married to a

Uprichard. There were four Bowmans: Dad (boilerman); Stanley (dressing

machine); Walter (labourer) and May (winder). I

also worked with Stewart Walker when we whitewashed all the buildings.

Gerald Sparrow was in charge of bleaching, Harry Smyth was a joiner and

Harry's brother was winding master. Albert Pollock and Davy Johnston

were at bleaching. Davy's father was watchman at night. Manager

McCandless lived at the back. Mr Wilkinson was floor manager William

McAdam transported materials from Belfast by horse and van. The other

dresser was Jimmy McMaster There were two men working on damask looms,

Scott and Flanagan � I think they went overseas to work.

Annie McClenaghan (nee Ball) provides a lifetime recollection of work in

a linen mill: I started work in Culcavey Factory as a

Weaver at the age of 14. This was the main work place for most of the

girls and women of the village and my mother introduced me into the

intricacies of the trade. It was hard work and the youth of today would

probably be horrified by the conditions under which we toiled, the

noise, dirt and the cold. We put in a six day

week, Monday to Friday 8.00 a.m. to 6.00 p.m. and Saturday 8.00 a.m. to

12.30 p.m. More than welcome was the cup of tea we got at our loom at

10.00 a.m. When 12.30 p.m. arrived it was lunch break, but we had to be

back at work at 1.00 pan. For some it meant a `piece' (sandwiches)

consumed on the premises, but a .few managed to run home for a quick

bite.

The weavers' tools were a haddle hook (held

in your mouth all day) and scissors (held in your hand all day). The

women staved off the dirt by wearing an overall to save their clothes.

If your loom stopped functioning the men would be called on to do the

repairing or .fixing, but as time meant money to the weaver the women

sometimes became just as adept at the fixing and carried their own

tools. I remember one method I was involved in was the supply of small

cuttings of dry rabbit skin glued and put in the shuttle to stop the

weft breaking. As my father Hugh was the main supplier of rabbit skins

in the area I was often sent post-haste home to procure the necessary

bits of skin. Another necessary task was cleaning the looms every

Friday. We were the producers of the best damask table cloths, tea

towels and deck chair covers, the latter of which would cut the hands

off you. The weavers' tools were a haddle hook (held

in your mouth all day) and scissors (held in your hand all day). The

women staved off the dirt by wearing an overall to save their clothes.

If your loom stopped functioning the men would be called on to do the

repairing or .fixing, but as time meant money to the weaver the women

sometimes became just as adept at the fixing and carried their own

tools. I remember one method I was involved in was the supply of small

cuttings of dry rabbit skin glued and put in the shuttle to stop the

weft breaking. As my father Hugh was the main supplier of rabbit skins

in the area I was often sent post-haste home to procure the necessary

bits of skin. Another necessary task was cleaning the looms every

Friday. We were the producers of the best damask table cloths, tea

towels and deck chair covers, the latter of which would cut the hands

off you. The terminology of the workers is

ingrained in everyone who worked in the linen trade. The warp winding,

weft winding, slashers, lapping, drawing in, bobbin hole, tenter,

fitter, reel bleaching, yarn drying, cloth passer, joiners,, fitters

etc.

Jimmy McNally and Stanley Bowmen were slashers, Matt Spence was the

tenter, George Gunn, Bertie Cairns and Jim McCauley .fixed wood on the

looms. Norman Chapman and Cecil Harrison were fitters (fixing metal on

the looms). Jimmy Walker put stoppers on hand shuttles, not a very nice

job as you had to suck them. George Humphries swept the floor all day

long to try and keep the dust and dirt down.

The

company and the fun we had are what memories are made of If a girl was

getting married she was put into the weavers' truck covered in french

chalk and pushed around the mill. The

company and the fun we had are what memories are made of If a girl was

getting married she was put into the weavers' truck covered in french

chalk and pushed around the mill. I worked in the

mill for 18 years until it was closed in 1967. My redundancy was �101

and I really thought I was rich! But the hard work didn't put me off,

because I continued my trade in the Ulster Weaving Company in Sandy Row

for another 24 years. For people who worked in the

mill many would ask the question "How do you know a mill worker?" and

the answer would be "They all speak loudly"! To those

who spent the days toiling in the linen trade they not only remember the

working conditions but also the people they worked with. One such person

was Mr William Johnstone from Hillsborough, the night watchman

responsible for closing all the gates and making his rounds of the

factory. His hurricane lamp lit up many a dark night. It was also his

duty to stop and start the dynamo-driven engine which produced

electricity for the village and to keep the boilers lit until the

boilerman came to work at 6.00 a.m. in the morning. The harsh and

hazardous conditions that the mill people worked in would not be

tolerated today. From the cleaning of the coal fired boilers where a man

had to enter the boiler and chip (de-coke) all the limestone which had

accumulated and remove it outside for disposal. Pitch dark inside and

without ventilation or light there were no safety regulations here. The

cold, noise and humidity were horrendous. Gas could be seen rising from

the pots that the yarn was steeped in. Chemicals including vitrol and

clard lime were used. Masks were unheard of then. The dust, known as

pouse, covered everything, including the workers. James

McCandless, known to his workers as `Pa McCandless', was a respected and

feared man. He not only held sway over his workers in the mill but also

in their family lives. This was the man who could give you the `sack'

and deprive your family of a home. But he ruled the factory and the

village houses with vigilance, and appeared to know everything that was

going on. He had a wealth of experience to call upon in his capacity as

Manager as he had successfully managed a factory in Russia in his youth.

His honeymoon was spent sailing on the River Volga. Armed men approached

him after the Russian Resolution and asked him to manage the factory for

them. The Manager's house was situated towards the back

of the mill on the left-hand side. A one-storey structure well enclosed

in its own grounds. A well-tended garden extended to the left of the

house, kept weed-free and full of vegetables, fruit and flowers, by the

gardener/handyman employed by the Mill. Pa McCandless and his wife had

one daughter called Annella. Miss Alice Taggart, who lived in No. 16

Hillside Terrace with her sister, was employed as their Housekeeper.

Miss Taggart spent her retirement in Hillside Terrace and lived to a

ripe old age. For the people who worked in the Factory

their experience of the hard work, the laughter and the tears, the

sharing and the caring could produce a book in itself. These were the

days when you walked to work, or if you were indeed lucky made your way

by bicycle, from not only Culcavey but also Hillsborough, Maze and

surrounding areas. Time was strictly monitored and you had to be

punctual no matter how far you had to travel. At the beginning of the

day you entered to the thunderous sound of the mill at work, and many of

the workers became adept at lip-reading, so great was the noise. What

many of the weavers and winders earned was governed by what they

produced. A bad batch of yarn would mean a meagre pay packet. Here was

one big family, each reliant on the other in the effort to produce high

quality linen.

OGLES GROVE FARM

Ogles Grove Farm was built on part of the land that would have been

Bradshaw's Nursery. Bertie and Norma Higginson lived here until they

emigrated to Australia in the 1950's. In the late I920s the area which

is now called Eglantine Park was still covered with shrubs and trees

which were removed with the aid of a steam engine. As Norma Higginson

recalls life on the farm was vastly different to what it is today.

After the Second World War agriculture in Northern Ireland was being

boosted along with new ideas, more up-to-date machinery, and new

ventures were the order of the times. My late husband, Bertie, had taken

delivery of a new Nuffield tractor (the first in the area), his

ambitions were to increase our acreage and make Ogles Grove Farm larger

and more productive. The 'factory land' as it was known, became

available for renting, this was just across the road and too good to

miss. We increased our acreage of potatoes the first year (1948/49). The

land had not been tilled for some years so it grew excellent crops in

those early years. Our herd of dairy cows was

producing milk. for the factory residents who lived alongside at

Culcavey in those red brick and grey pebbledashed rows of houses, just

beyond Mr Emerson's shop. Granny Higginson would deliver, on her

bicycle, the gills, pints and quarts of fresh milk required every

morning. Milking commenced well before breakfast. The big white cow

always had first attention; her milk would be oozing onto the byre floor

before we even started. The `kicker' was always left to the last, she

had to be leg roped, otherwise her foot would end up in a full bucket of

fresh milk! The family cats sat nearby, and it was fun trying to squirt

milk to their lips, often missing and ending up around their whiskers!

Ogles Grove Farm produced early vegetables .for the Lisburn market

and local shops. Bertie grew early cauliflowers. I remember well that

each plant had to have one teaspoonful of Sulphate of Ammonia sprinkled

around its base, just as the head was starting to develop.

The three hothouses grew early lettuce, followed by a crop of

tomatoes. Nothing beat a fresh young tender lettuce, with home made

dressing, garnished with young tomatoes. The

railway line divided two fields from the main part of the farm. One

frosty morning we could hear the train whistle blow frantically.

To our amazement a sow with ten suckling pigs had ventured onto the

line. Fortunately they scattered in all directions, so the 10.00 am

train had a clear passage to the Hillsborough Station just half a mile

away. This was counted as a close shave as the sow and her family should

not have been there! The early fifties brought new

horizons to our lives. There was a big movement of people to Canada and

lots of families were losing their sons and daughters to this great

continent. Australia seemed very far away. We had connections there, and

letters had been coming and going since the early thirties. In those

early years the letters referred to droughts and more droughts, with sad

tales of shooting sheep and horses as the crops had .failed. However,

after the war, pasture improvements took over in the heavier rainfall

areas around the Riverina in New South Wales. Times had greatly improved

� the wool boom had given the farmers a great boost, people were

prospering and life was much easier. During

1952/53 Bertie travelled to see for himself what the life and

opportunities were like in Australia. He spent twelve months studying

farming in Australia and New Zealand. He was fortunate to see four

seasons in Australia and judge for himself. He returned in October 1953

with news that opportunities were many `down under' � land was plentiful

and reasonable compared to Northern Ireland and England.

A big step was taken and early in 1954 Ogles Grove Farm was sold to

the Walker family, who farmed the land until it was sold for private

building. On 17th March 1954 we set sail on the SS Orsova, making her

maiden voyage, to Australia. There was Bertie, myself and our two

children, Carole and John. Much water has passed

under the bridge since those early days of married life in Culcavey. It

has been experience that my family has never regretted making.

THE VILLAGE & ITS PEOPLE

From Smithy Row, English Row, Shop Row, Hillside Terrace, Thompson's

Row, Puddledock Row, the houses were the property of the Mill. The

houses were `tied', one member of the family had to be employed by the

Linen Company in order to attain and maintain tenancy. The fear of

losing a job was bad enough, but it also meant losing a house. From Smithy Row, English Row, Shop Row, Hillside Terrace, Thompson's