|

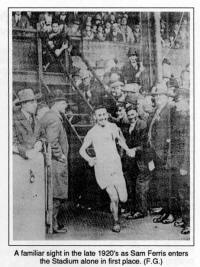

SAM FERRIS "MARATHON

MAN"

BY TREVOR MARTIN

Most of us this summer enjoyed the spectacle of the

greatest of the worlds athletes gathered in Barcelona to

compete for Olympic gold. The marathon, held over 26 miles

represents for many the pinnacle of endurance, tactics and

true grit. The games of 1924 were held in Paris and anyone

who watched the film "Chariots of Fire" would have been

given a good impression of the period, styles and equipment

of the runners.

There were many famous names at these games Paarvo Nurmi

winner of nine gold medals, Eric Liddell who refused to race

in the 200 metre final because it was held on a Sunday,

Johnny Weissmuller winner of five swimming golds and later

to become the screen Tarzan. Amongst all these world famous

characters was a man from the town of Dromore, Sam Ferris,

one of the greatest distance runners that Northern Ireland

and the United Kingdom was ever to produce, made his Olympic

debut.

Sam Ferris was born in the townland of Magherabeg near

Dromore in August 1900 which coincidently was the year of

the second Olympic Games, also held in Paris. Sam's mother Minnie

Clarke was said to be a bit of an athlete and it was not

unknown to see her running through the fields hurdling the

stooks of corn. Sam lived for the early period of his life

at Magherabeg, however he moved to Glasgow with his father

when his mother tragically died. They only stayed in Glasgow

for a few years, returning to Dromore to the rest of the

family. Sam was like his mother, always interested in

running and at the early age of seventeen he joined

Shelteston Harriers, winning many prizes in the Junior Open

Category.

Olympic Games, also held in Paris. Sam's mother Minnie

Clarke was said to be a bit of an athlete and it was not

unknown to see her running through the fields hurdling the

stooks of corn. Sam lived for the early period of his life

at Magherabeg, however he moved to Glasgow with his father

when his mother tragically died. They only stayed in Glasgow

for a few years, returning to Dromore to the rest of the

family. Sam was like his mother, always interested in

running and at the early age of seventeen he joined

Shelteston Harriers, winning many prizes in the Junior Open

Category.

Sam was also used by the local pigeon men to run in the

rings of the first birds home as there was only one pigeon

clock in the Town, thus giving them an extra time advantage

over their colleagues.

When Sam was eighteen the First World War had been raging

for four years, so like most young men of his age he decided

to join up. He joined the fledgling Royal Air Force, then

known as the Royal Flying Corps and on enlistment he was

posted to India. During that posting, however, he did little

or no running, preferring to devote his energy to other

sports such as football. After his service was up he

returned to Dromore, once again taking up his first love of

running. He didn't have to wait long for success winning

many local races including the Co. Down One Mile

Championship.

In December 1923 he rejoined the Royal Air Force and was

stationed in Uxbridge where he competed in a cross country

race. Although he only came third his talents came to the

notice of Bill Thomas of Herne Hill Harriers who persuaded

him that his true forte might be long distance rather than

cross country running. Bill Thomas's entreaty had an effect

on Sam and he joined Herne Hill Harriers with whom he stayed

throughout his career. Many young men who had fought in the

war were taking to serious athletics, Bobby Mills who had

been awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross in the Royal

Flying Corps won the 1920 Polytechnic marathon, although

prior to the race had never run further than 14 miles. Sam's

first 20 mile race was not a success so it was important for

him to build up the stamina necessary for long distances.

In

the 1924 Olympic trials there were 80 starters one of whom

was Sam Ferris competing in the first ever marathon race of

his career. Despite conditions being poor and a lack of

experienced runners in the field, by the 23 mile point 3

runners were well in the lead. Ahead of Sam in first and

second place were Duncan Wright and Jack McKenna. McKenna

was in all sorts of trouble and collapsed with exhaustion

just past the 25 mile point. Ferris, although exceptionally

strong, could not catch the Scotsman Wright who finished in

2.53.47, only 45 seconds in front. It would appear therefore

that Bill Thomas was right and Sam's talents lay in the

longer distances. It was as a result of this achievement

that he was picked for the British Olympic team to compete

in Paris in 1924. In

the 1924 Olympic trials there were 80 starters one of whom

was Sam Ferris competing in the first ever marathon race of

his career. Despite conditions being poor and a lack of

experienced runners in the field, by the 23 mile point 3

runners were well in the lead. Ahead of Sam in first and

second place were Duncan Wright and Jack McKenna. McKenna

was in all sorts of trouble and collapsed with exhaustion

just past the 25 mile point. Ferris, although exceptionally

strong, could not catch the Scotsman Wright who finished in

2.53.47, only 45 seconds in front. It would appear therefore

that Bill Thomas was right and Sam's talents lay in the

longer distances. It was as a result of this achievement

that he was picked for the British Olympic team to compete

in Paris in 1924.

The marathon team for the Olympics was Jack McKenna,

Duncan Wright and Sam Ferris and of the three runners who

finished in the best position. The heat combined with the

route chosen for the course, much of it over cobbled roads,

led many including Wright to drop out; the only time that

Wright was ever to fail to complete a marathon. Sam's fifth

place in 2.52.26, behind the eventual winner Alban Stenroos

of Finland was the best achievement to date for a British

runner in an Olympic marathon. The achievement is even

better when we see that at the 23km mark Sam was 30th and

even after 35km was only 9th. The omens looked good, what

might he achieve in future years as it is generally thought

in the world of running that marathon runners reach their

peak much later than those at the shorter distances?

Sadly for Sam he was to be bitterly denied Olympic gold

for although he competed in two further Olympics, (Amsterdam

in 1928 and Los Angeles in 1932) the gold was tragically to

elude him. It was the 1932 games in Los Angeles that was

perhaps to prove to be his greatest disappointment for

through a combination of fate and bad management he lost the

gold medal. In later years he was to relate this story, one

that best illustrated the lack of a co-ordinated and

professional approach on behalf of the administrators of the

British Olympic team in those early days. When Sam and

Duncan Wright arrived they were given no briefing on the

course, indeed Sam only saw the course once before the

actual race. In contrast Juan Zabala of Argentina, the

eventual winner had trained on the course and knew it

intimately. On race day they were given their British

running vests to find that they were much too long and they

both felt that it would be a disaster to use them in the

competition. Duncan Wright was adamant he would not use the

vest and he eventually competed wearing his own Scotland

vest. Sam tried to redesign his vest cutting some eighteen

inches off it's length, but this was to prove catastrophic

during the race. After a distance into the race the vest

began to ride up Sam's back exposing the kidney area to the

wind and causing it to chill. He stopped several times

during the race to adjust the vest eventually, holding it

down using the safety pins that held up his number. Despite

this he ran well coming up through the field until he had

Juan Zabala in his sights. Once again Sam's backup team were

to let him down. He was told Zabala was going well and to

ease off for the silver medal. The truth was that Zabala had

been through a difficult period in the race and was on his

last legs. A concerted attack by Sam at this point would

possibly have

finished him off. Sam finished 2.31.55, only nineteen

seconds behind Zabala and won the Olympic silver medal, with

both runners breaking the world record.

Sam eventually got over his disappointment and raced on

for many years, increasing his tally of awards and honours

both national an d

international. He won the first ever AAA title to be

contested, was victorious in eight consecutive Polytechnic

marathons and was runner up in the first Empire Games in

1930. d

international. He won the first ever AAA title to be

contested, was victorious in eight consecutive Polytechnic

marathons and was runner up in the first Empire Games in

1930.

He set a course record in Turin of 2.46.18 beating the

Belgian, French and Italian champions. They even came to

England to get their revenge but, he destroyed them winning

in 2.40.32 a margin of five minutes. Course records were his

speciality, in Liverpool he came home in 2.33.00 some

fifteen minutes in front of the next man.

Sam, a strict non smoker held strong views on marathon

running and indeed training in general. A newspaper article

written in 1931 said of him

"In order that the novice may evaluate Sam Ferris, he

must do as Sam Ferris did, train wisely, train

conscientiously and train

consistently. Spasmodic bursts of energy serve no useful

purpose."

His training for any marathon began some eight weeks

before the race and was set to a strict regime, one that he

kept to and which served him well.

As a Warrant Officer in the Royal Air Force Sam served in

many stations throughout the world over the years, at Dieppe

in 1940 he was the officer in charge of evacuating the men

prior to the advancing German Army.

Henry Fairley a local man and relative of Sam remembers

spending time with him, his wife and daughters in India in

1938. Sadly Sam died in the late seventies but his widow

Marjorie is still alive and living peacefully in a cottage

in Rosson-Wye, England. I'm sure that many who read this

story will like me be proud that a man from Dromore has

written his name into Olympic history.

I would like in my article to acknowledge the help of

Seamus McKeown and Henry Fairley for the invaluable

information that they supplied in compiling this incredible

story of surely one of Dromore's greatest sons.

TALE OF A

TOWNLAND

BY MARTIN CAMPBELL

Extracts from a thesis written by Martin Campbell,

Belfast in the Spring of 1992. The Townland of Islandderry

lies 3 miles to the west of the town of Dromore.

One of the first signs of settlement in the area is the

"crannog" in Islandderry lake - a man made island supported

on oak beams and reached by a causeway. It was used as a

place of safety by both man and beast. In the early 19th

century a dug-out canoe and oars were found nearby. The lake

itself was man made in prehistoric times and in the 17th

century stretched to over 20 acres. Today, with constant

drainage schemes it has been reduced to approximately 2

acres. Flowing across the north of Islandderry and dividing

it from the neighbouring townland of Gregorlough is the

Shankerburn, the

main

stream in the area, it flows into the lake. main

stream in the area, it flows into the lake.

Prior to the rebellion of the Irish Catholics of October

1641 the townland was the property of Art Oge Mac Glaisne

Magennis. Following the defeat at the hands of Cromwell in

February 1642 Art Oge had to forfeit his lands to the Crown.

The first proprietor was Alexander Woodall/Waddell from

Moffat Hills in Lanarkshire, Scotland, who paid a quit rent

of �5.13.4 to Art Oge for 679 acres, 3 roods and 4 perches.

This was the beginning of a long association between the

Waddell family and Islandderry.

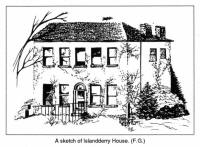

Alexander Waddell built Islandderry house on the site of

a rath overlooking the surrounding countryside, across the

Lagan, as far as the

Mournes. Mournes.

A two storey building, it was built in a style similar to

the peel houses of lowland Scotland. Interesting features of

the house are a well in the basement and a reputed escape

tunnel running from the house and coming up on the other

side of the Lagan about a mile distant.

Alexander Waddal married Elizabeth Hamilton and over the

next hundred years or so his progeny quietly prospered in

the area. Thus the Islandderry estate came down through the

Waddell family into the possession of Robert (b. 1752

d.1810). This description of him was given to Lord Downshire

by Thomas Lane of Hillsborough with whom he, Robert, had had

a serious difference of opinion "as garrulous as an ignorant

and uninformed man may be". Robert's son James (b.1782

d.1859) fought under Wellington's command in the Peninsular

War retiring with the rank of Major to Islandderry. He was

responsible for the closing of the old county road and the

building of the road round the lake - now the Lough Road -

for which he was paid one shilling by the County.

Catherine Meade Waddell (b.1790 d.1869) also lived in

Islandderry House at this time. A spinster lady, she

undertook the building of the first, and only school house

in the townland. Built 200 yards from the site of a former

hedge school, it consisted of one large classroom and a

further two living rooms for the teacher - a Mistress Mary

Milligan.

In the second Report of the Commissioners of Irish

Education Inquiry of 1826 one, James Murphy is listed as the

Headmaster at an annual salary of �19.0.0.

It was a fee paying school of the Church Education

Society and by 1858 had 56 children male and female, 22 of

whom belonged to the Established Church and 34 were

Presbyterian. The school cost �53 to erect.

Thirty pounds being donated by the Waddell family and

twenty three pounds by the Church Education Society of

Kildare Place, Dublin.

Since 1938 the building has been home to the Kilntown

Orange Lodge.

On the 31st of October 1796 the Islandderry Yeomanry was

formed with Robert Waddell as Captain. When they were

disbanded in 1803, by which time James Waddell was

Commandant, he was given two inscribed Irish silver

two-handed cups "As a token of their respect, gratitude and

esteem" One still exists in New Zealand - the other was

stolen. Others named in the Yeomanry records are Wm. Boys,

Jn. Magill, Joseph Hanna, Jn. Harrison and Lieut. Wm.

Nicolson.

Although, at the time of the Art Oge land forfeiture the

population of the townland was only 18 (16 Scots and English

and 2 Irish), with the coming of the outside landlords there

was an influx of people to farm the land. Many small farms

were rented out by the Waddells, the main one being

Islandderry Farm about 1.5 miles north east of Islandderry

House on the road to Hillsborough. Originally comprising 295

acres it had grown by absorption of the surrounding land,

until, in the mid 19th century it stood at 426 acres. Today

it is 457 acres.

The Griffith Valuation of 1863 shows the townland

supporting 19 small farms ranging from Mary Jane Waddell 117

acres to Samuel Gooley with only 2 acres. Other names listed as being tenant

farmers are Poots, McMurray, Preston, Savage, Patterson,

Colter, Isabella McAvoy, Beggs and Downey. Many of these

names are now periferal to the townland. As the land was

fertile, with little or no bog, the main crops grown were

barley, potatoes, turnips and corn. Any spare was usually

taken into Dromore market.

Gooley with only 2 acres. Other names listed as being tenant

farmers are Poots, McMurray, Preston, Savage, Patterson,

Colter, Isabella McAvoy, Beggs and Downey. Many of these

names are now periferal to the townland. As the land was

fertile, with little or no bog, the main crops grown were

barley, potatoes, turnips and corn. Any spare was usually

taken into Dromore market.

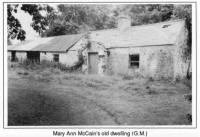

Behind the old McCain house, there is a disused quarry.

The rock, known locally, as pigeon rock, is a baked and

hardened limestone - a poor marble. In more recent years it

has been used for road surfacing although it would have

originally been quarried to feed the lime burning kilns in

the area notably at Moira and the aptly named Kilntown two

miles from Islandderry.

The population peaked just before the famine in 1841 with

211 people in 34 families. Although the area was not

directly affected by the famine (there was only one rumoured

incident of a mother and child dying by the wayside above

Shankerburn) the population began to decline. Along with

other areas within a 30 mile radius of the city Islandderry

began to feel the draw of industrial Belfast. People drifted

towards it in search of work and entertainment. Many also

emigrated to America, New Zealand, Canada and mainland

Britain. Waddell's, McCains', Dempsters' all left.

Land

purchase schemes, and in particular, the Northern Ireland

Land Act of 1925 gave many tenant farmers the opportunity to

buy their land. Those in Islandderry were no exception and

so without an annual source of income from rents the

Islandderry estate began to decline. Land

purchase schemes, and in particular, the Northern Ireland

Land Act of 1925 gave many tenant farmers the opportunity to

buy their land. Those in Islandderry were no exception and

so without an annual source of income from rents the

Islandderry estate began to decline.

It was sold by Timothy Waddell to Mr. and Mrs. Bertie

Wilson. At the beginning they lived in Alexander Waddal's

old house but when they began to renovate it, it was

discovered to be virtually beyond repair. A new family house

was built one hundred yards away and Islandderry House now

lies forlorn and derelict. The main staircase has collapsed,

ceilings are down and the basement impenetrable. Mr. Wilson

died last year and the estate is managed as a dairy farm,

under the name Island Dairy, by his remaining family.

Islandderry farm lay empty for many years supposedly due

to local superstition that bad luck went with the ownership

of the house.

Former owners include a Mr. McClelland from Banbridge and

a Major Beaument from Lurgan. It is now owned by Prima

Farms, a large company whose land agent is Mr. Draffin of

Dromore.

Although new houses abound Islandderry is no longer a

close-knit farming community. Only three of today's

residents were born in the townland. Many of the old

homesteads are derelict, but a twenty-five minute drive, by

way of the Hillsborough by-pass and the Ml, brings you into

Belfast. Islandderry has been transformed into perfect

commuter land.

According to parish Records for the period 1829-39,

several children born in Islandderry were baptised in the

Cathedral

as follows'.-

10th May 1829-Margaret of Samuel and Margaret

McCullough

21st May 1830-Anne of John Lamb and Susan Smyth

3rd April 1832-Marcia of Denis and Marcia Martin

15th July 1832-Michael of John and Susan Lamb

21st April 1833-Matthew of John and Jane Little

21st February 1834-David of William and Jane McKay

27th August 1837-Rosetta of James Morgan

20th September 1839-Elizabeth of William and Sarah Moore

By 1863 only Smyth and Moore were still living in the

townland whilst the Littles had moved to Gregorlough fifty

yards outside the Islandderry Boundary where their

descendants still live today.

September, 1992

Dear Martin,

Just to bring you up to date. Oats and barley are growing in

the fields. A new baby boy has arrived who is a Dempster

descendant. All is well in the townland of Islandderry!

R. McM.

RENT AT ISLANDDERRY 1st NOVEMBER, 1892

| Tenant |

Rent

Half |

Poor

Rate |

Cash |

| |

�.s.d.

|

�.s.d.

. |

�.s.d |

| John Arlow |

9.10.0

|

4s.4d.

|

9.5.8 |

| Mr. J. Thompson

|

10.0.0 |

4s.7d.

|

9.15.5 |

| Win. Dennison |

17.10.0 |

8s.0d.

|

17.2.0 |

| I. Smyth |

5.15.3

. |

2s.7d. |

5.12.8 |

| F. Beckett |

17.0.0

|

17s.10d. |

16.12.2 |

| J. Woods |

21.5.0

|

9s.9d.

|

20.15.3 |

| |

81.0.3

|

1.17.1

|

79.3.2 |

| Receipts for hay and grazing

|

January 1893 |

�204.0.0 |

|

| Rents |

January 1893 |

�237.19.9 |

|

Source-Waddell Letters D2129/1 - Proni.

BALLYKEEL SCHOOL IN THE DAYS OF MASTER CRAWFORD

BY ANDREW DOLOUGHAN

"But past is all his fame. The very spot where many a

time he triumphed is forgot."

These lines by Oliver Goldsmith on "The Village Master"

have kept recurring in my mind since I decided to pen this

article on Ballykeel Public Elementary School, which once

stood almost opposite the Orange Hall on the Dromore

Ballynahinch Road.

To-day not a brick of the old building remains. For a

time after its closure, in 1939 I'm told, it was converted

into a bungalow. But eventually it was demolished, and Mrs.

Ena Graham now occupies the handsome new bungalow within its

precincts.

Around the same time the neighbouring school at Drumlough

was also closed and pupils from both centres were

accommodated in a new and much more commodious building on

the road leading from Drumlough Cross Roads to Ballykeel

Cross Roads.

Both the old schools had been blessed for a lifetime with

very gifted teachers - Mr. and Mrs. Sam Crawford at

Ballykeel and Mr. and Mrs. Charles Craig at Drumlough. Mr.

Craig continued to hold sway in the new school until around

1943 when Mr. Richard Beattie was appointed principal,

bringing gifts to equal, if not indeed surpass, anything

that had gone before. I speak with first-hand knowledge Mr.

Beattie, who was the master of Ballyvicknakelly School in my

closing years there, and who is still remembered with

affection and gratitude.

Mrs. Craig taught with Mr. Beattie at Drumlough until

about 1947 when he was joined by his wife Nancy.

MASTER FOR 28 YEARS

"Time and change are busy ever," and after 28 years as

the master at Drumlough Mr. Beattie decided to call it a day

in 1971, but his wife continued for the short time that

remained until the new school was also closed and the pupils

transferred to Anahilt and Dromara.

From here on I continue the story of Ballykeel School

with the help of one who had his education there and who has

very happy memories of his school days and of the Master and

Mrs. Crawford.

Needless to say, the present-day boys and girls have

little conception of what school days were like in the

1920's and 1930's, when this Province was getting back on

its feet following the Great War of 1914-18.

I was curious to know if my friend had ever used a slate

and slate pencil in his time at school. Of course he had,

and when the master ran out of slate pencils they went to

the "Golf' a quarry across the road - got a slate stone,

cracked it and used the pointed end as a pencil, "and you

could have written the very best with it," said Tommy.

That's not his name, but we'll call him that.

There were no free books or pencils in those days. You

had to buy your own and you didn't get fooling about and

destroying pages.

They were too precious, and the master would have "cut

the knuckles off you if there was any nonsense."

The slates were only used for lessons around the

blackboard, but at the desk it was a case of pens or pencils

and notebooks. Mr. and Mrs. Crawford were both well versed

in the art of calligraphy and the pupils had Vere Foster

headline copy books as a means of improving their writing.

I'm not sure if it's still there, but a house in Great

Victoria Street, Belfast, carried a plaque to the memory of

the inventor of this copy book.

COAL MONEY

In those days the classrooms were heated by means of coal

fires, and pupils had from time to time to take coal money

to help keep these fires stoked up.

Another thing which we take for granted nowadays is

electricity, television and radio. At the time of which we

are thinking most homes were lighted by means of oil lamps

or candles. The invention of the Tilley lamp, which gave

much better light, was a great boon.

The first TV programme which I can recall seeing was in

1952 at the time of Queen Elizabeth's accession to the

throne. Prior to that some of the well-to-do homes had

battery radios.

We got round to discussing the contents of school reading

books, and "Tommy" bemoaned the fact that the reading

supplied to the schools nowadays is not nearly so appealing

and does not place the same emphasis on morals as did the

stories and poems in the old school readers.

Our conversation turned to dress. "No school uniforms

then," said "Tommy" with a chuckle. "You were lucky if you

had something to wear that was handed down, even if the

trousers had a patch to keep your shirt tail from sticking

out. And for the boys it was all short trousers then and

stockings with turn-down tops. Some had trousers with

buttons at the knees. Most boys and girls had to keep good

the clothing they wore at school. Something less good was

used for romping about on Saturdays and at other times, and

for Sundays there was usually something better."

A PAIR OF CLOGS

"As to footwear, it was a case of bare feet or a pair of

'gutty' shoes in the good summer days and a pair of clogs,

which had wooden soles, in the bad winter days. Locally,

most of the clogs were made by Rabbie Watson of Gallows

Street."

But even then school had its light-hearted moments.

"Tommy" re-lived one of these as he recounted times when

Master Crawford might leave the room for a wee chat with a

local farmer who might be passing by with his horse and

cart.

This was the signal to start up a bit of dance-band music

using the partition wall between the two class rooms to drum

on. Never once did Mrs. Crawford try to stop this. Rather,

"Tommy" thought she enjoyed the whistling and singing, "for

she was a real musician and a very nice woman." But when the

master returned a "court martial" began and the musicians

usually got two or three slaps apiece.

Like most schools, Ballykeel had a poem about the master,

and it ran something like this:

Sammy Crawford's a nice wee

man.

He tries to teach us all he can.

To read and write and `rithmetic,

But he's the boy can use the

stick.

McADAM'S CROSS ROADS

Leaving Ballykeel School we took up our stand in heart

and mind with the boys who assembled at McAdam's Cross Roads

mostly in the long summer evenings. "One would have thought

there was something wrong if there weren't at least a dozen

or more there," he said.

The crack was always good, and one had a choice of a game of

skittles, marbles, quoits or football - the latter in the

"Sticky Park," a field off the Ballykeel Road. Occasionally

there might be a bit of a concert, the music being supplied

on violin, mandoline, flute or mouth organ.

We went over the names of some who frequented the Cross

Road and were shocked to find that few of them are alive

to-day. Names that readily came to his mind were - John

Gamble, Sandy, Willie and Stanley Young, Billy Porter, John,

Sandy and Sam Gourley, Jim Chambers, Billy Shannon, Rabbie

Armstrong, Jimmy, Tommy and Willie Hamilton, John Hunter,

Bob, Hugh and Tommy McClune, John Doloughan, William,

Geordie and Sammy Wilkinson, Sam Allen, Joe Gamble, Jimmy

and Willie Wallace, Willie Coulter, John Wilson, Herbie

Scott, Sandy Steele, Jimmy Scott, Billy and Jim McNeill,

Fred Jess, Willie Jess, Sammy Jess, Jimmy Tinsley, David

Black, Walter and Jim Black, Sam and David Gibson.

Vehicular traffic in the years of which we are speaking

was very light. Cars most frequently seen on the

Ballynahinch Road were those owned by the late Joseph

Lindsay (The Leader), Hawthorne Bennett, Robert J. Poots,

Jack Bailey, Hugh Corbett and the renowned Harry Ferguson,

who had been a pupil of Ballykeel School.

The thought of the few cars in the countryside then

prompted "Tommy" to remark "It's a nightmare on the roads

now, and until the powers that be cut down the speeds that

cars are able to do it will be no better."

Another thing he doesn't agree with is the driving test.

He feels that passing the test gives some people the

impression that they have nothing more to learn about

driving - and that's all wrong, he says.

We went on to recall one of the motor bikes in the

district in those days. It was owned by the Rev. William

Bill, minister of Drumlough Presbyterian Church, who kept a

few stones in the side car to steady it on the road.

Mr. Bill's successor was the Rev. William Copes - "a man

in whom the congregation placed great confidence." As an

entertainer he is remembered for his ability to recite such

delightful pieces as "I'm living in Drumlister in clabber to

the knee" (by the Rev. W. F. Marshall) and "The man with one

hair".

The precentor of Drumlough Church Choir was John Gibson,

a handloom weaver who also played the violin. He lived

between McAdam's Cross Roads and Ballykeel Hill, the sloping

banks of which are a reminder that it was much steeper a

lifetime ago.

At the roadside by John's home was a blacksmith's forge,

run by John Magowan, whose brother Nelson is well known in

the district. Another brother, the late Sam, was the Member

of Parliament for Iveagh for some years. Another smithy to

operate at the forge was Ernie Hanna.

Towards the foot of the hill Mark Hamilton had charge of

McAdam's Cross Roads Post Office. He also sold sweets,

groceries and paraffin oil. The Post Office is now located

at The Pole on the Leapoughs Road, and the postmistress is

Mrs. Annie Sudlow.

"GROVEY'S LODGE"

Near Ballyvicknakelly School there met a group known as "Grovey's

Lodge." This consisted of a number of young men from the

district who congregated in the evenings in the home of Hugh

Watson, known in the area as "Grovey" because he resided at

Watson's Grove.

The "crack" there was always good. If any of the group

got a bit of news about any of the others, their latest

romances and so forth, the idea was to arrive first and have

"Grovey" primed so that he could let the cat out of the bag

when the "lodge" was in full flight.

I close with a warm word of thanks to "Tommy" for his

time and interest. I'm sorry he chose to remain anonymous,

but that wish I must respect.

|

|

|

"THE BUFFS"

THE ROYAL ANTEDILUVIAN ORDER OF BUFFALOES

by

WILL PATTERSON |

The RAOB Buffs Lodge No 4294 was formed in Dromore in the

early 1920's and met in the premises of John Murphy in

Bridge Street. After meeting in a few other locations they

moved to premises beside Alma Lodge in Castle Street and

around 1935 eventually moved to the Crown Hotel in Meeting

Street where they had a Buffs Hall in the Crown's yard. The

RAOB order was a benevolent order and like the Masonic order

it helped educate the children of deceased members. The

order is open to members of all religions.

The members have to pass degrees at risings, which are

conducted by the Grand Lodge in Ireland. Members are

presented with degrees and Jewels suitably inscribed. One of

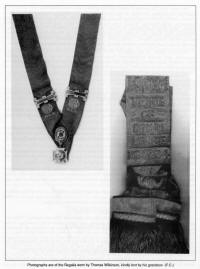

the oldest medals the present writer has seen was a Knight

of Merit jewel which was presented to Thomas Wilkinson, Boot

and Shoe repairer formerly of Bridge Street, Dromore. It is

a 9ct. gold medal, with the date May 1923. He also had the

worthy Primo jewel and also a sash with the RAOB 4294

presented also.

The members of the Lodge had an annual outing each year

and went around the Co. Down coast. They held Christmas

parties for children each year.

One of the first secretaries of the Dromore 4294 Lodge

was Arthur Beattie, Rampart Street, who was manager of

Josiah Ward's public house in the Square. Another secretary

was W. J. Thompson of Iveagh Terrace who had been a colour

sergeant in the army. Ernest V. Copling who was Chauffeur to

the Graham family, Clarence McMurray of Meeting Street and

John Aherne of Maypole Park filled the role of secretary

over the years until with the passing of time the lodge was

disbanded in the 1980's as most of the members had passed

away.

This ended the Buffs in Dromore after a period of over 60

years and those who had sought to keep the lodge going

included B. Bingham, W. D. Kelly, Ed. Poots, J. Aherne, Ed.

Boal, C. McMurray, V. McMurray, W. J. Wilson, G. Lilley, K

Lindsay, W. H. Gamble and Robert Gailey.

DROMORE'S PIPE DREAM

BY HUGH R. MOORE

It was thought for many long centuries that Troy (of the

Wooden Horse) was just a name used by the Greek poet Homer

in his famous poem about a fictious war. Then when ancient

Troy was discovered and excavated in 1870, it was realised

that the poem was not fiction but an account of a real place

and a real war and it was also discovered but there had been

possibly ten Troys built and destroyed in battles with their

enemies. Why, you ask, begin an article on a sewerage system

by a reference to ancient Troy? - for this reason; when we

visited this ancient site some years ago we were surprised

to see that it had had a sewerage system; partly open

drains, which had to be helped to perform their function,

but also there were crude pipes excavated in the ruin,

probably dating back to the 13th century before Christ.

Sewerage systems are as old as intelligent man - wherever

people have come together they have been part of organised

life. It is easy, using a little imagination, to see how the

necessity arose. Take Dromore (or any other town, but we are

interested in Dromore) - many years ago the `road', then not

much more than a track, known later as the Old Coach Road

(running from Carrickfergus to Dublin), passed through

Drummor, it became Dromore. The river could be forded there

and so it became a stopping place. First a cottage would be

built, then another, then one or two crude dwellings until

gradually a small settlement appeared. As it grew provision

had to be made for the traveller and the inhabitants. It

became more complicated with each new dwelling. The open

field, the dry toilet, the open drain into the river and

later, much later, a crude septic tank. As the town grew

there was a tangle of pipes and drains, all heading towards

the river and every new dwelling added to the problem. I

remember seeing one of the open drains which had been

covered and was revealed during excavation. In our

imagination we can see the little village developing around

the muddy square.

During the early years of the century small schemes were

carried out from time to time, trying to improve what seemed

to be unimprovable. Each householder and merchant was a law

unto himself and parts of `The System' were always giving

trouble. With the passing years more voices were saying that

something would have to be done. At this time Commissioners

were responsible for the affairs of the town and knew about

the problem. When the Urban Council was formed in 1922 they

inherited this difficult question and the matter was raised

and discussed from time to time but, what with a war just

over and with various money problems, it was postponed, but

never allowed to be forgotten. Money was gathered from

various sources. For instance, in May 1940 it was reported

at a Council meeting that a sum of �1,000 was available to

the Council and it was decided, on the proposal of Dr. J. C.

Wilson, that it be invested in War Loan until the Council

was in a position to take the matter up. The years rolled

by, and as soon as the second World War was over, while

there were many pressing needs, the Council decided to move

as quickly as possible for the system that did exist was

fast failing. Ultimately, after due consultation with the

appropriate government departments, in particular with the

Department of Health and Local Government, on the 20th of

January 1948 the Clerk informed the Council that the plans

for the proposed sewerage system had been sent to the

Government department responsible. Suitable loans had been

established and tenders for the work were sought.

On the 11th August of that year the Council received five

tenders for the construction of the system. The lowest was

received from Messrs John Graham and Sons, as the firm was

then known. The tender price was �77,947 eight shillings and

five pence - a large sum in those days. This tender was

accepted, it was pointed out that the firm undertook to

carry out the work in 30 months. The Council was also

informed that the Government would meet 66�/�

per cent of the cost. Most of the rest of the cost it was

thought would have to be raised through the rates.

It was known at the time that it would cost much more, it

did! - over �50 thousand more and this did not include all

the other work that was necessitated because of the scheme.

When it was known that the green light was on for the

scheme, the people of the town were delighted, for it would

mean the end of dry toilets and weekly cleansing by the

scavenger brigade of the Council. However, as was

anticipated, there were going to be difficulties, as happily

they were few. The very favourable weather during the

initial months meant that the river was low and this

facilitated the installation of the pipes in the river bed

and the concrete casing over them.

The flat concrete surface along the river bank proved to

be an attraction to the children, who ran along it were in

danger of slipping off it, which could have been fatal if

the river were in spate. This was raised by Mr. Francis

Russell and the Council discussed it. It would seem there

was no action that could be taken. Also with so much

excavation there were many tracks in the roads. This

resulted in a number of claims for broken car springs.

When the pipes were laid and the system operating, the

various householders had to make the connection. Some were

initially unwilling to do so and for some time the two, or

perhaps several, systems were in operation. This, of course,

was a small matter compared to the task of providing toilets

for 70% of the houses which had only the dry toilets. This

took time, but it was achieved. For some years the Council

continued to be responsible for some rural cottages. During

the digging of the trenches not only did the contractor come

up against stubborn rock but, in some ways more difficult,

there were the pipes of many centuries impossible to tell

where some of them came from or where they went to. I

remember the trench in the Square as being very deep.

All this helps us to understand the difficulties of the

scheme. The disposal works were situated at the town end of

Holm Terrace on ground purchased for this purpose; the main

pipe running along the path on the right-hand side of the

river going towards Holm Terrace. On a number of occasions

cattle on the south bank of the Lagan came across when the

river was low and did some damage to the filter system in

the disposal plant.

After the system was fully established it was stated that

it was at full capacity and for this reason it would be

unlikely that the town would be able to develop further.

However, when some of the first of the new estates were

anticipated, it was found that the capacity could be

increased by pumping stations and other means. The High

School was the first to benefit by this and, as we all know

and rejoice in, there have been some very large and valuable

developments since it was said that `Dromore will not be

able to develop because .....'

I remember an interesting experience when the work was

almost finished. One of the engineers whom I had met offered

to take the late S. J. Duffy, who at that time owned the

bakery shop in Church Street, and myself to see the disposal

works at Holm Terrace and to explain the workings to us. The

two things I remember from this experience were that,

according to the engineer, we could drink the water that

flowed from the system - neither of us volunteered!!

The other thing I remember was when Mrs. Duffy was giving

us a cup of tea afterwards, the engineer explained that to

put the tea in first and then add the milk was a colloid and

to put in the milk first and then to put in the tea was a

solution. Chemically, he seemed to indicate, they were two

different drinks.

On second thoughts - was it the other way round? the tea

first - a solution, and the milk in first a colloid. Well,

it is one or the other. Perhaps I am confused - like the

original tangle of pipes under Dromore!!!!!

Thanks to Messrs. I. Bill and D. Leeman of

Graham's Dromore for their help.

|