George Rawdon and Lisburn

By George McBratney

Have You ever wondered what impression a stranger to Your town might

receive about its history if he were to spend an afternoon

examining its. public memorials and statues?

Have You ever wondered what impression a stranger to Your town might

receive about its history if he were to spend an afternoon

examining its. public memorials and statues?

To take an example, the busy and prosperous Lagan valley town of Lisburn has had a history as exciting and dynamic as any in the British Isles. Yet what evidence is there to demonstrate that this town was once a frontier post of great strategic importance and the scene of out standing industrial achievements?

In Market Square there is a permanent fixture of John Nicholson, who lived in Lisburn for a time before he found glory in India. In Castle Street there is a monument to the dead of two world tears and on the high ground in the Castle Gardens stands a gun which has seen service against the Russians at Sevastopol.

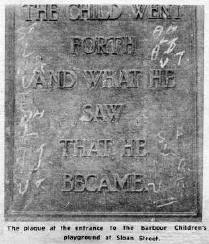

In fact the people of Lisburn seem to be encouraged to remember their military heroes. A notable exception is the homely bronze inscription on a playground in Bridge Street: "And the child went forth, and what he saw he became."

MUNROE

Suppose now that the stranger were to venture among the people of Lisburn and try to discover from their conversation something about the people whose efforts made the town what it is. He would almost certainly learn something about Harry Munroe, hanged in Lisburn for his part in the 1798 rebellion.

Perhaps he would hear about the piper whose head was shot off in the Battle of Lisnagarvey - the old name of the town - the head which, rolling down a hill, caused the place to be known as Piper Hill. (The stranger might well wonder whether some confused person mistook a cannonball for a head).

He would hear many anecdotes about people remembered because they were involved in a spectacular context. And sooner or later someone would mention the economic development of and tell of the technical skills brought to the Lagan Valley by Louis Crommelin and the Huguenots.

The odd thing is that the stranger might learn least about the man who, more than any other, established Lisburn as a community in Ulster.

RAWDON

George Rawdon was born in 1604. At that time Lisburn was little more than a break in the woods valued by the native Irish for its proximity to the Lagan. And around it, in that part of South Fast Antrim known as Killultagh, the forces of the British crown battled to clear the area of Irish and to make it sate for the coming of English settlers.

The king granted land to those who had proved they could

defend it, and one captain whose ferocity was rewarded, Sir

Fulke Conway, received the territory of Killultagh among his

gains. He encouraged the establishment of a small settlement

of about 52 immigrant families and by the time George Rawdon

arrived in the early 1630s to manage the Conway estate a

castle had been begun, a church had been built and plans were

afoot for a school.

Fulke Conway, received the territory of Killultagh among his

gains. He encouraged the establishment of a small settlement

of about 52 immigrant families and by the time George Rawdon

arrived in the early 1630s to manage the Conway estate a

castle had been begun, a church had been built and plans were

afoot for a school.

These early settlers, whose job it was to stay, farm and -

fight in the Lagan Valley, faced two great problems.

The first problem was to ensure that the area developed

economically. Sir William Brereton defined it very clearly

when he wrote in 1635:

"The town belongs to my Lord Conway, who hath there a good handsome house . . . Here aboutes, my Lord Conway is endeavouring a plantation; though the land hereaboutes be the poorest and barrenest I have yet seen, yet may it be made good land with labour and changed.

STRUGGLE

In their continuing struggle to change their environment by their labour, the settlers were led by George Rawdon. From the, letters which passed between the Conways and Rawdon it appears that their main concern in the thirties was to create a well stocked estate from which cattle could be exported.

Much of the burden of organising the estate fell upon Rawdon, who was continually attending to the wants of tenants and employees. Letters relating to the estate followed him, wherever he went, and since the Conways tended to be absentee landlords, the early successes in establishing trade in salmon. butter and cattle may be traced to his efforts.

It is interesting to note that the Irish parliament of 1661 frequently called upon his services, especially to give information on the horse trade between Ireland and England.

But Rawdon was more than a skilful estate manager and a successful farmer. He was also an enterprising industrialist. Although his name is linked with the early establishment of iron works near Lisburn, it was not until after the stormy period of the .civil war and Commonwealth that Rawdon could plan to manufacture with any confidence.

SECURITY

Then, during the comparative security of the Restoration he turned with greater vigour to the production of glass, soap, stockings and potash, and there is ample evidence that he encouraged the local manufacture of the material for which the Lagan Valley, and Lisburn in particular, was to become world famous:

"I got four barrels of hemp seed and four of flax from Ostend to furnish our neighbours with" he informed Conway in 1667.

Rawdon never found his task easy. Throughout the collection of his letters to Conway, he complained continually about the lack of money, about the difficulty of getting in rents and the poverty of the people. He had many failures, as he confessed to Conway in 1665:

"I have been burnt in the hand with projecting the setting up of manufactures here".

Nevertheless, the change which Sir William Brereton had anticipated in 1635 occurred within the lifetime of George Rawdon. By 1697, another writer found it possible to invoke the Conways' plantation as a model of what settlers could achieve:

"There is in the North of Ireland an estate which was the Lord Conway's. 'I'his estate was first purchased by Sir Foulke Conway for about £500. The rent roll is now about £5,000 per annum. 'Twas altogether a wood, as the name of Kilulta (the wood of Ulster) denotes, and yet in the memory of men now living has been improved by a colony of Yorkshire people and others brought over and settled by lord Conway and managed by Sir George Rawdon".

PROBLEM

The second problem that faced the settlers brought over by Conway

was how to secure the conditions in which this process of

change might be begun and continued. It must be remembered

that for much of the 17th century, Lisburn was a frontier

post, a settlement of immigrant families in an area described

by Sir Arthur Chichester in 1601 as "one of the strongest

holds of the native Irish in Ireland."

The second problem that faced the settlers brought over by Conway

was how to secure the conditions in which this process of

change might be begun and continued. It must be remembered

that for much of the 17th century, Lisburn was a frontier

post, a settlement of immigrant families in an area described

by Sir Arthur Chichester in 1601 as "one of the strongest

holds of the native Irish in Ireland."

The only claim of the settlers to the land lay in military conquest, and it would have been most surprising if the native Irish had not turned against the invaders the methods by which the land had been gained.

The Irish uprising came in1641, and in that year George Rawdon added another role to that of estate manager. The Irish were thwarted in their attempt to take Lisburn, and of the battle Sir Arthur Tyringham wrote to Conway:

"You shall from others what has been done and by whom in the defence of your town of Lisnagarvey. Captain Fisher behaved incomparably as did Mr. Rawdon."

Then of course, the struggle between King Charles and his parliament became a civil war, and in the period of divided loyalties that followed, Lisburn was occupied by the soldiers of both parties to the fighting.

But even when Charles II came to the .throne in 1666, George Rawdon, now a major for his services, refused to relax his vigilance. He still feared retaliation by the native Irish.

"We are, my Lord" he wrote to Conway in 1666, "at present very, apprehensive of some trouble this year and the Irish are much discontented.'"

SUSPENSE

And once, when the suspense became too great for him Rawdon went so far as to arm 20 of Conway's tenants. He was not to know that Lisburn had already survived the greatest threat to its existence in its history.

Lisburn was in fact, a town of some strategic importance. A defending force there controlled a section of the river Lagan, and it lay on the vital communication route between Carrickfergus and Dublin.

Rawdon knew this and it was part of his life's work to fight like a proud imperialist to retain military control of the town.

POWER

It would hardly be fitting to conclude this survey of George Rawdon's work without saying something about the part he played in the affairs of the town itself. As the Conways' land agent, the permanent official of t he great estate, Rawdon had an amount of power that we today do not even give to our councils.

We have no way of assessing the injustices that Rawdon may have been a party to, but there is no doubt that he did much valuable work in 17th century Lisburn.

His attention to the roads for example, won him this tribute from a traveller of 1683:

"All the highways within eight or ten miles of Lisburn are very good - not only for the nature of the soil, which generally affords gravel and sand, but Sir George Rawdon's care, who is, I believe, the best highwayman in the kingdom, and the industry of the inhabitants."

Rawdon worked extremely hard for his position as first citizen.

"I seldom see Mr. Rawdon but noon and night" his wife complained in a letter to Conway. But the office had certain compensations. When Conway was away Rawdon enjoyed a social eminence and it seems to have been a custom for townspeople to gether at his house at Christmas.

It was his privilege to dispense Conway's venison at intervals. But such details of personal enjoyment occur rarely in the family papers. 'The people were, after all, members of an imported culture enclosed within a frontier town, and the native Irish were never far away.

With the duties of `mayor' Rawdon sometimes combined those of sheriff. On one occasion, he wrote that he sent two horse thieves to jail, then to their death by hanging. He also felt himself to be guardian of the population's beliefs, which is the greatest temptation of power.

"Our neighbours here that conform not to the Church" he informed Conway in 1669, "grow very confident. They have built oratories for themselves almost in every parish."

He had no misgivings about enforcing the `Five Mile' Act, and it is no coincidence that the Presbyterians of Lisburn made their first application for a permanent minister after Rawdon had died.

Perhaps I ought to add that intolerance, at that time, was church policy and had the approval of Jeremy Taylor, the most renowned churchman ever to have lived in Lisburn.

It would have taken rare qualities in a man of that to have confined his local powers to patronage, the throwing of occasional parties and the upkeep of roads.

Some of you may by now have formulated the question: if George Rawdon was so important in the early history of Lisburn, why has Louis Crommelin replaced him in popular memory as the greatest hero of the town's economic advance?

There are a number of reasons for this. First, the arrival of Crommelin and other Huguenots in Lisburn is a well documented event. You have to go grubbing for facts about 17th century Lisburn, but the flight of the Huguenots from France and their dispersal is a story that has been told many times by historians.

People can learn more about Crommelin than about Rawdon.

Secondly the Huguenots are associated with that industry for which Lisburn later became famous - linen. Naturally, we remember the man who was responsible for introducing the technical skills that were to lead to economic prosperity and win the acclaim of the world for the produce of Lisburn.

Thirdly, it has been widely believed that Lisburn was a place of no importance before the Huguenots came, and historians have done little to contradict this assumption. G. L.. Lee, for example, a historian of the Huguenots in Ireland, writes that:

"The venture - of the linen industry - was started in the ruined town of Lisnagarvey, rebuilt for the purpose by the refugees."

Such a statement must be read with care. It is quite likely that the town of Lisburn and the area around it suffered during the Williamite wars. But some Huguenots arrived there before the wars in Ireland began, and one of them Pierre Goyer, established the manufacture of silk in Lisburn in 1688.

It is certain that Lisburn was not devastated as it had been in 1641, or a historian who accompanied Schomberg could hardly have written in 1689:

"On Monday the second of September we marched through Lisburn . - . This is one of the prettiest inland towns in the North of Ireland, and one of the most English like places in the Kingdom."

DEVELOPMENT

We shall never know for certain whether Lisburn Was a ruined town or a living community when the Huguenots arrived. But what we can say is that of all the factors that made possible the tremendous economic development of Lisburn under the Huguenots, the life's work of George Rawdon was one of the most important.

We can also be certain that Rawdon would have approved the policy of bringing over workers with special skills, since he himself had suggested that course many times, though it is interesting to reflect what would have been his reaction to their type of Protestantism.

No doubt many of you would like to know what Rawdon was like as a person. It is more difficult to discover anything about this aspect of his life than any other, since we can only rely on the record of his labours.

The papers of the time do not tell us whether Rawdon had the warmth of personality that success in everyday relationships requires. No novelist or playwright would attempt a character sketch on the evidence available.

The historian, at any rate, can admire his foresight, his acceptance of responsibility in many forms and his use of power for the public good. His motto, like that of his contemporary, Wentworth, might have been `thorough'.

SETTLEMENT

As soldier, citizen and economist he attended to everyday details without ever failing to plan for the future. It ought to ' be impossible to 'overlook the importance of George Rawdon in the history of Lisburn. He died in 1684.

Within 50 years of his arrival in Lisburn the -tiny and vulnerable settlement surrounded by wood and bog had become a centre of civilisation and economic activity.

In our own time, when there is so much interest in economic affairs and personalities, it seems odd that we should have forgotten George Rawdon.