- Front Page

- Editorial

- Contents

- Relations between Landlord, Agent & Tenant

- Landlord & Agent

- Landlord & Tenant

- From Whoredom to Evangelism

- History of the Parish of Drumbo

- Prehistoric occupation of Dunmurry

- Suffolk House

- Ernest Blythe

- Health and wealth in the borough of Lisburn

- The growth of Lisburn had begun.

- The fever hospital, Dublin road

- Book Review

- Historical Journals

Lisburn Historical Society, Volume 2 pt.3

Volume 2 • December 1979

HISTORY OF THE PARISH OF DRUMBO

J. F. RANKIN

IT IS DIFFICULT to find any references to the

district in the first millennium A.D. All we know is that the Lagan

Valley was an area inhabited by man from early prehistoric times; the

circular earthwork and megalith known as the Giant's Ring bear testimony

to the presence of man around 2000 B.C. There are remains of forts of

the early Christian period at Farrell's Fort on Fort Road, Ballylesson

and at Tullyard.

IT IS DIFFICULT to find any references to the

district in the first millennium A.D. All we know is that the Lagan

Valley was an area inhabited by man from early prehistoric times; the

circular earthwork and megalith known as the Giant's Ring bear testimony

to the presence of man around 2000 B.C. There are remains of forts of

the early Christian period at Farrell's Fort on Fort Road, Ballylesson

and at Tullyard.

Drumbo - DRUIM BÓ -the ridge of the ox - is one of several townlands of that name in Ireland. Hogan1 lists three townlands of the name in Cavan, one in Fermanagh, one in Monaghan and one in Antrim. The Latin form of the name, COLLUM BOVIS, occurs in the Life of St. Patrick by Muirchu, in the Book of Armagh, but, although there is a local tradition that St. Patrick founded a monastery here, this can be no more than conjecture. Archdall,2 writing in 1786, quotes this association, his source being an early seventeenth century Irish historian, Father John Colgan. However, modern scholars are now fairly certain that this reference is to some place of the same name, not now identifiable, on the Quoile estuary owing to its specific reference to being near the sea and close to saltmarshes and also to its position in St. Patrick's itinerary quoted by Muirchu.

The earliest written reference to Drumbo is found in the Martyrology of Tallaght, a calendar of Irish Saints written about 800 A.D. Here we have two saints listed:

| July 24 | LUGBEI | DROMA BÓ |

| August 10 | CUMMINE | AB DROMMA BÓ (Ab = Abbot) |

We cannot be certain that these references are, in fact, to the Drumbo under discussion, but if they are, then we have evidence of the existence of an ecclesiastical centre here, without doubt a monastery, at this early date. We have, of course, no means of knowing the actual dates at which these two individuals were living, although Archdall3 states that Commine was Abbot at the beginning of the seventh century, again using Colgan as his source.

A much later Martyrology, known as the Martyrology of Donegal, was compiled in 1630 by Michael O'Clery, a lay brother of the Order of St. Francis of strict observance in Donegal and, incidentally, one of the Four Masters. He also lists the same saints on July 24 and August 10 but further defines Cuimmin as Abbot of Drumbo in Uladh, the ancient Celtic name for the north-east corner of Ireland. Later references to this saint become Mochumma where the prefix mo- is used as an expression of endearment and devotion.

In chronological order, our first recorded event appears in the Annals of Ulster at the year 1003 A.D. There took place in this year 'the battle of Craebh- telcha, between the Ulidians and the Cinel-Eoghain,. It is now thought that this place is Crew Hill near Glenavy; the Cinel-Eoghain, coming from the lands we know as County Tyrone and beyond, were invading Ulidian territory cast of Lough Neagh. In the battle the son and brother of Andgar, King of Ulidia, were slain and 'havoc was made of the army', the Ulidians being defeated. 'And the fighting extended to Dun-Echdach and Druim-bÓ, these being the present day townlands of Duneight and Drumbo.

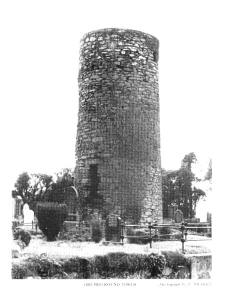

We cannot say with any degree of certainty when the Round Tower, the stump of which is all that remains of this early settlement, was built. These towers were being built throughout Ireland from the ninth until the twelfth century. Within the monastic community, they served many purposes. They were bell towers - the Irish word CLOICTHEACH means bell tower - and small hand bells would have been rung from the uppermost storey which usually had four openings, one to each of the cardinal points. They were beacons and served to identify the whereabouts of the church; it has been shown that many monasteries lay on the early routes followed by travellers. Lastly, and perhaps most important, they were used as places of safety and refuge in which to keep the precious books and plate of the monastery and to which to retreat in times of attack by raiders. Hence the feature of the door being at first floor level which prevented (usually) the floors inside being set afire by raiders. The Miscellaneous Irish Annals4 record the plundering in 1130/31 of `DRUIM BOTH, including the Round Tower, and Oratory, and books': the ward `oratory' - DUIRRTHEAC - is generally accepted as referring to a wooden church, as opposed to one built of stone. Wood was the usual building material in eastern parts of the country at this period and the evidence shows that Ireland was heavily wooded from the earliest times until the seventeenth century.

The Round Tower was excavated in 1841 under the

direction of the then rector of the parish, Rev. Horatio Maunsell with

Mr. Durham of Belvidere and Mr. Edmund Getty, a noted antiquarian. In

the account of this excavation,5 Getty states that a human

skeleton was found, lacking one arm and both legs below the knee. Petrie6

suggests that this burial was there before the tower was built and that

the builders did not wish to disturb it; whether it was a Christian or

pre-Christian burial is open to doubt.

![]()

The Christian church in Ireland from the sixth century was monastic in character, parochial and diocesan administration not being introduced until early in the twelfth century. There were literally hundreds of churches; in recent research, Dr. Ann Hamlin has identified no less than 266 sites with some vestige of ecclesiastical occupation within the six counties of Northern Ireland alone? Many of these would have been monastic settlements similar to that at Drumbo. We might suppose that the monastery of Drumbo would have been the centre of a settlement of considerable population, with a church, graveyard, cells in which the monks would live, guesthouse, refectory, kitchen and workshops, probably surrounded by a boundary wall. The land outside the wall would have been given over to arable and stock farming with orchards, gardens and meadows, worked by clients of the monastery, to which they paid tithes.8 During digging in 1950, some pieces of souterrain pottery were found? thus providing evidence of domestic activity during this early period.

Although we have no evidence to tell us that Drumbo was a centre of great intellectual activity, many monasteries were centres of learning and artistic development. The justly famed illustrated texts and manuscripts which have come down to us were inscribed by monks and the sculptured crosses, illustrating biblical scenes, were fashioned under the direction of the church, just as, in the later mediaeval period, the great French cathedrals told the stories of the Bible in sculpture and coloured glass.

During these centuries, the secular history is one of tribal warfare and the Annals are full of tales of battles between the many Kingdoms in Ireland. One such occurred in 1130 A.D. and the Four Masters give the following account in the Annals:

'An army was led by Ua Lochlainn into Ulidia. The Ulidians assembled to give them battle. When they approached each other, a fierce battle was fought between them. The Ulidians were finally defeated and slaughtered, together with Aedh Ua Loingsigh, lord of Dal-Araidhe, Gillaphadraig MacSearraigh, lord of Dal-Buinne, Dubhrailbhe MacArtain, and many others besides them, and they plundered the country as far as the east of Ards, both lay and ecclesiastical property, and they carried off a thousand prisoners and many thousand cows and horses. The chief men of Ulidia, with their lords, afterwards came to Ard-Macha to meet Conchobhar, and they made peace, and look mutual oaths and they left hostages with him'. It seems likely that this is a fuller description of the same event recorded in the Miscellaneous Irish Annals mentioned above.

Dal Buinne (later anglicised to Dalboyne) took its name from the race of Buinne, son of Fergus who was a King of Ulster in the years before Christ. This people occupied a tract of land on either side of the river Lagan, extending to the shores of Lough Neagh, and roughly comprising lands which in later times became the baronies of Upper Masserene with portions of Upper Castlereagh and Lower Iveagh.

The Anglo-Normans began to colonise Ireland in the twelfth century; initially the colonists came to the south eastern ports but gradually they spread their influence throughout the more distant parts of the country. De County succeeded in penetrating the north of the country, setting up his headquarters in Downpatrick in 1177, from where his followers penetrated much of the present counties of Down and Antrim. The surviving evidence of the Norman period can be seen in the huge earth castle mounds which they built; these are known as mottes and some form of defensive structure, probably of wood, would have been constructed on top of them. Mottes, some with their associated baileys, can be seen in many places in eastern Ulster; we have three in our area, one at Belvoir, one at Edenderry and one at Duneight, this latter being built on top of an earlier Celtic rath.

The Synod of Rathbreasail in 1111 is generally considered to be the date at which Ireland was divided into dioceses and parishes; during the ensuing years the diocesan administration, much of which is still with us today, began to take shape. The boundary of the Dioceses of Down lay farther north than it does now and we can assume that Drumbo must have been one of the original parishes within the dioceses.

Our first known record of the parish is in 1258 when Pope Alexander IV granted 'Dispensation at the request of the Archbishop of Armagh to Master Adam, rector of Drumbo, and perpetual vicar of Bangor, in the diocese of Down, value together 12 marks, to hold one other benefice with cure of souls'.10 Towards the end of the thirteenth century, we begin to read of Papal taxations. These were necessary, primarily, to provide funds to finance the losses which the Vatican had incurred in fighting the wars in the Holy Land. The earliest taxation of which a full record remains took place in 1306 during the reign of Pope Clement V. The list of parish valuations for most of Ireland has been preserved; those for Down, Connor and Dromore have been the subject of a detailed study by Reeves,'' a noted antiquarian scholar in the last century and Bishop of Down from 1886 until his death in 1892. The Diocese of Down comprised a total of 126 rectories, vicarages and chapels, divided into five deaneries:

-

Clondermod (now part of Connor, roughly the parishes east of Lough Neagh)

-

Blaethwyc (the mediaeval name for Newtownards)

-

Ards

-

Lechayll (Lecale, the early tribal land of Leth Cattail)

-

Dalboyn (the early tribal land of Dal-buinne, cited above)

In Reeves classification, Drumbo appears to have

been the parish with the highest valuation within the deanery of Dalboyn.

![]()

'THE CHURCH OF DRUMBO, WITH THE CHAPEL. 3 MARKS. TENTH 4S'.

The chapel to which the reference is made is, of course, St. Malachi's of Cromlyn - now Hillsborough. The remaining parishes in Dalboyn were Drum (Drumbeg), Cloncolmoc (probably near Dunmurry), Ardrachi (Derriaghy), Blaris (Lisburn), Drumcale (Magheragall), Lennewy (Glenavy), Rathmesk (Magheramesk), Enacha (Aghagallon), Thanelagh (Tamlagh, near Aghagallon), Acheli (Aghalee) and Derbi (Ballinderry).

The church of Drumbo, in the graveyard of the Presbyterian Church, is no longer visible, nor is it possible to carry out any excavation due to the number of interments both within and close to its walls. It was a few yards to the south east of the Round Tower and was quoted by Harris, 12 in 1744, as being 45 feet in length and 20 feet in breadth and in ruins. We have no means of knowing when the church, to which these measurements refer, was built; it is indeed probable that there had been a succession of churches on the site, as we know there had been a wooden church in the monastic period and the later parish church was clearly of stone. Equally we do not know when it fell into ruins, but this was a fate shared by many churches in the late mediaeval period. Bishop Echlin's visitation of 1622 refers to Drumbo as being ruinous, although there was clearly sufficient stonework visible to be measured when Harris visited the site a century later.

For almost 300 years until the first decade of the seventeenth century, no records have survived of the parish. A single reference can be traced; Leslie and Swanzy's Succession Lists for the Diocese of Down give Oddo Yealty as Vicar in 1500, their source being the Irish Annates. It is said that he was a clerk in the Diocese of Connor and held the vicarages of Drumbo and Craigavad in Down together with the rectory of Inystade or Ballyscullion in Derry. We are now arriving in the era of plurality, that is, the holding of several benefices by one incumbent in order to augment his income, a practice which was to become very widespread in succeeding centuries.

Dalboyn was held by the Normans at least until the middle of the fourteenth century. Following the murder of William de Burgh, Earl of Ulster, in 1333, an inquisition held to ascertain the extent of land in his possession included the deanery of Dalboyn.13 However, in the following years, the Normans began to lose their hold in Ulster and the land was gradually re-possessed by the Irish. The barony of Clannaboy, which approximated to the modern north of County Down from Bangor to the river Lagan, came under the lordship of a branch of the O'Neill family from Tyrone; indeed the name Clannaboy is derived from an O'Neill name AEDH BUDH, Hugh the Fair. The territory remained under the chieftainship of succeeding generations of O'Neill, until finally Con O'Neill was dispossessed in the plantation of the early seventeenth century.

REFERENCES

1. Hogan: Onomasticon Goedelicum, Dublin 1910 p.358

2. Archdall: Monasticon Hibernicum, London 1786

p.119

3. Ibid pA19

4. Miscellaneous Irish Annals, ed O'hInnse, Dublin

1947 p.19

5. U.J.A., Series 1, Vol. 3, 1855 p.110 IF

b. Petrie: Ecclesiastical Architecture of Ireland,

Dublin 1845

7. Hamlin: unpublished Ph.D. thesis in Q.U.B.

Library

8. Hughes/Hamlin: The Modern Traveller to the Early

Irish Church, London 1977

9. An Archaeological Survey of Co. Down, Belfast

HMSO 1966 p.297

10. Calendar of Papal Registers Vol. 1 p.356

I I. Reeves: Ecclesiastical Antiquities, Dublin

1847

12. Harris: The Antient and Present State of the

County of Down, Dublin 1744 p.73

13. Orpen: JRSAI 1913

I would like to thank Or. A Hamlin of the Historic

Monuments & Buildings Branch of the Department of the Environment

and the staff of the Linen Hall Library for their help in preparing this

paper.

![]()

A PREHISTORIC OCCUPATION IN DUNMURRY

By CLAIRE SLOAN

NOT EVERYBODY appreciates the full prehistoric

wealth of their own environment, but it is quite possible that some

fields near you may contain evidence of a past prehistoric occupation in

the form of a few shards of fragmented pottery or worked flint.

NOT EVERYBODY appreciates the full prehistoric

wealth of their own environment, but it is quite possible that some

fields near you may contain evidence of a past prehistoric occupation in

the form of a few shards of fragmented pottery or worked flint.

Unfortunately too often the word Archaeology conjures up a picture in some peoples' minds of the salvaging of priceless jewels and treasures. Few people show interest in the objects of intrinsic value dating from earlier periods such as the Mesolithic (middle Stone Age) 7000 B.C. -Neolithic (New Stone Age) 3500 B.C. - or the Early Bronze Age 2000 B.C.

Very little practical knowledge about these periods are taught to the general public. Therefore the majority of people in this Province would be unable to recognise a stone age implement. Sadly people often retrieve remains in the wrong way, e.g. by badly documented field surveys where finds go unreported to the local museum and are lost, or by retrieving metal items from the ground by means of metal detectors. This new fad has been promoted by Treasure hunting societies whose members are either misguided or simply motivated by self profit and have been responsible for the loss of many metal items without record or taken out of context as a single item is useless to the archaeologist.

However, if a survey for example in a field is carried out and all significant finds are reported to the museum a small valuable contribution can be made to the local archaeology of your district.

Such a survey was carried out by me under the supervision of an archaeologist from the Ulster Museum.

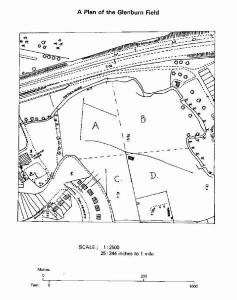

A surface collection of flints was made in a ploughed field in Dunmurry overlooking the Glen River (see map). The field appeared to be in a prime position for a past prehistoric occupation situated on a slight slope overlooking the Glen River and the sandy nature of its soil indicated good drainage, suitable for a settlement site. Traces of prehistoric occupation were discovered in the form of a few worked flint flakes and therefore a more careful search was made and the material found was looked at in relation to other prehistoric sites in the Lagan Valley area.

Method of Approach:

-

The field was surveyed and surface collections were made from the whole area.

-

A 25" map was obtained and a plan of the Glenburn field was drawn, dividing it into four quadrants.

-

The flint which appeared to be worked was bagged, labelled and classified.

-

Records were made on each flake on its character, condition, length and patination.

|

Quad A yielded: |

Quad B yielded: |

|

3 cores |

27 flakes (15 retouched) |

|

Quad C yielded: |

Quad D yielded: |

|

26 flakes |

38 flakes

(26 retouched) |

The material discovered in this field was not

unsimilar to another published site situated in Dunmurry Lane about 300

metres from Glenburn field. The Greenoge Hearth site in Dunmurry Lane

was excavated in 1928 by Blake Whelan1 who uncovered a

Neolithic Hearth and small worked flakes, cores and blades. As well as

this, embedded in the upper layer of one of the trenches 38 fragments of

undecorated Neolithic pottery was found. The Dunmurry pottery is of

major significance as it has been suggested by Case that this was the

earliest Neolithic pottery in Ireland.

![]()

It is possible that late Mesolithic and early

Neolithic communities may have lived together at Glenburn or they may

have occupied the fields at different periods.

It is possible that late Mesolithic and early

Neolithic communities may have lived together at Glenburn or they may

have occupied the fields at different periods.

Other prehistoric sites of similar period are located nearby at - Blaris, Derriaghy, Ormeau Bridge, Malone Road and the ritual site of the Dolmen at The Giant's Ring.

The Dunmurry site may have been used by prehistoric man as he travelled along the river camping for short periods and picking up flint in the vicinity and using it.

The valley would have provided a good hunting ground with fish in rivers and an inexhaustible food supply of game and wild fowl. They may also have used its timber and reeds here and were within reach of the belt of cretaceous exposures if they needed more flint.

From this evidence found it does at least provide some traces left by prehistoric man in Dunmurry. Since such a survey is just skimming the surface it would be difficult to make any absolute statements on their lifestyle or movements in this area as this would be making too sweeping conclusions on a period which still presents so many unsolved problems.

However Dunmurry may have served as a strategic crossing point from the Newtownards area to Lough Neagh and beyond.

How to recognise a Flint worked by Man

Flint which has been knocked off a core by a hammer stone, fractures in a recognisable way. It is characterised by certain distinguishable features:

-

bulb of percussion

-

ripple marks

-

striking platform

Some flints which have been described as being retouched means that small chips of flint have been removed from the flints side to help shape it into an implement.

GLOSSARY OF WORD TERMS

Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age). The people of the Mesolithic period 700 B.C. were a nomadic society who came to Ireland in post glacial times. They moved along rivers, lakes or coastlines hunting and gathering and settling for short periods in temporary seasonal camps living in huts. Their characteristic implements were blades and microliths (small triangular blade which was fitted into a wood socket to make a barbed harpoon head). During this time the making of pottery or practising of agriculture was unknown. The earliest evidence in Ireland for a Mesolithic dwelling place is at Mountsandle 7000 B.C.3

Neolitic (New Stone Age) 3500 B.C. - this period saw the introduction of food producing techniques and the making of pottery. These people were more settled but would never stay in the same location for more than a few years. Their characteristic implements were stone axes and arrowheads.

Core- the flint nodule from which flakes are struck

off..

Microawl - a Mesolithic implement which was small

and triangular in shape used for making holes in wood..

Bannflake - a late Mesolithic implement which may

have been used as a fish weapon..

Scraper - a Mesolithic, Neolithic or Bronze Age

implement 2 to 4 inches in length retouched round the sides and built up

at one end used for scraping hides of animal or wood..

Flake - this is the flint that is knocked of a core

and usually shows little deliberate retouch by man and is a most

elementary toolkit..

Coreaxe - Mesolithic tool which may have been used

as a digging implement..

Blade - a long knife like implement used for

cutting purposess

ILLUSTRATIONS LLUSTRATIONS LLUSTRATIONS

| B/2 | Worked Plate | A/6 | Scraper |

| C/41 | Partially worked leaf shaped arrowhead | A/5 | Scraper |

| D/55 | Bannflake | B/6 | Core/Axe |

| D/56 | Bannflake | D/68 | Worked Flake |

| A/4 | Microawl | D/8l | Scraper |

| D/80 | Scraper |

SUFFOLK HOUSE

By EILEEN BLACK

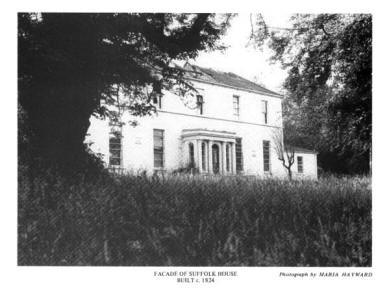

SUFFOLK HOUSE, the seat of the McCance family,

which John McCance, M.P. (1772-1835) made into one of the most imposing

residences in the area around Dunmurry, was last lived in by a member of

the McCance family in 1922/23. It was then purchased by a Mr. Gaffikin,

who owned it until 1927. The house then lay empty for ten years, until

it was purchased by Mr. G. A. Cameron, in 1937. The rooms of the main

part of the building, behind McCance's impressive facade, were used as

store rooms by the Ministry of Food during World War 11. In 1945, Mr.

Cameron leased this wing of the house to an Austrian refugee and

scientist, Otto Harriman, who established in it a small business, Ulster

Pearls Ltd., making artificial pearls. The factory which had the

distinction of making the pearls used on the Queen's wedding dress,

employed 160 workers (mainly female) in 1957, and occupied 10,000 sq.

feet of space, in this part of the house which was allowed to retain its

Georgian features.

SUFFOLK HOUSE, the seat of the McCance family,

which John McCance, M.P. (1772-1835) made into one of the most imposing

residences in the area around Dunmurry, was last lived in by a member of

the McCance family in 1922/23. It was then purchased by a Mr. Gaffikin,

who owned it until 1927. The house then lay empty for ten years, until

it was purchased by Mr. G. A. Cameron, in 1937. The rooms of the main

part of the building, behind McCance's impressive facade, were used as

store rooms by the Ministry of Food during World War 11. In 1945, Mr.

Cameron leased this wing of the house to an Austrian refugee and

scientist, Otto Harriman, who established in it a small business, Ulster

Pearls Ltd., making artificial pearls. The factory which had the

distinction of making the pearls used on the Queen's wedding dress,

employed 160 workers (mainly female) in 1957, and occupied 10,000 sq.

feet of space, in this part of the house which was allowed to retain its

Georgian features.

The Georgian wing of Suffolk House was built by John McCance in 1824, when he began to prosper. The facade, plain and undecorated, has a central porch with columns of the Tuscan order supporting an unadorned entablature. The dining room, which was to the left of the porch, has a fine plasterwork centrepiece in the ceiling, and large decorative medallions, cartouche-shaped, placed at regular intervals around the walls, at picture-rail height. The lime used in the plaster for these interior decorations, and for the outer walls, probably originated in the limestone outcrop on Collin and the Black Mountain.

The earlier wing of Suffolk House, lies behind the Georgian building, and at right angles to it. The walls, almost three feet thick, are of dark hand-dressed basalt stones, probably found locally, of various shapes and sizes. This part of the house, which is lived in by the Cameron family, consisted of kitchen, stable and farm buildings around a cobbled yard. The timber in the house is pine, while some oak has been used in the stables; the heavy roof timbers are held together with hand-made nails. Valuation survey records of April 1835 show that while the greater part of the entire house was nearly new at this time, and finished without any cut stone ornament, the stables and coach house were older and slightly decayed, though in good repair. The crowned chimneypots, which are used on the Georgian wing, are also found on this earlier building and were probably added c.1824, when McCance was unifying both old and new wings. The small gate lodge at the bottom of the driveway, has a hipped roof. There was a walled garden, with a gardener's house, on the other side of the Stewartstown Road (originally called the Upper Falls Road), where Glengoland Park now is; livestock were also kept in this area. Traces of paths which crossed the lawns of Suffolk House, and the remains of flower beds, long grown over, can still be seen in the grounds of the house.

Suffolk was a very picturesque area in the middle of the last century. The mountains and glens around Suffolk House were heavily wooded, and full of game. John McCance (1825-1869), grandson of John McCance, M.P., records, in his diary, seeing a fallow deer (a buck ) in the area, on 13th November, 1852; he gave chase with his beagles, but lost the deer in the glen. A stag was also seen in the glen, on 27th March 1856.

Suffolk House, at this time, was the centre of much social activity, with many balls being held in the house in the spring and summer months. John McCance says of one of these dances, that which was held on 23rd April, 1852: `Had a big dance at Suffolk which went off very well without anything disagreeable (sic) and everybody pleased with it the servants all a little through other the next day but not very bad (Tom lost key of garden gate)'.

The future of Suffolk House is, at present, uncertain. Ulster Pearls Ltd. are undecided about the possible restoration of their part of the house, while almost half of the earlier building is due to be demolished, due to the forthcoming widening of the Stewartstown Road. Sadly it seems likely that the house will become just another memory of the Suffolk area.

Sources:

- Miss C. M. Cameron, 'Suffolk' a project for Stranmillis Training College, 1957.W. A.

- McCutcheon, 'The Use of Documentary Material in the Northern Ireland Survey of Industrial Archaeology'.

- Valuation Survey Records, (VAL. IB: 128A), Public Record Office, Belfast.

- Journal of John McCance (1825-1869), Public Record Office, Belfast.

- Also information supplied by Mrs. G. A. Cameron, Mr. R. F. McCance and Mr. T. Q. Gaffikin.