- Front Page

- Editorial

- Fredrick Kee

- A glimpse of Blaris

- The Alms Houses at Ballycrune

- The life and work of Sir Richard Wallace Bart. MP.

- The war of 1812 through Irish eyes

- The early history of Drumbo Parish

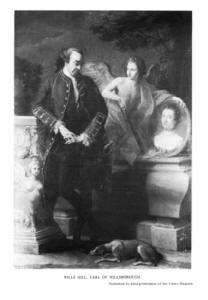

- A Portrait of Wills Hill, Earl of Hillsborough (1718-1793)

- John Wesley and early Methodism in lisburn

- Miscellanea from newspapers

- Historical Journals

A Portrait of Wills Hill, Earl of Hillsborough (1718-1793)

By POMPEO BATONI

On loan to the Ulster Museum, Belfast.

By EILEEN BLACK

IN

JULY, 1975, a large and impressive portrait of Wills Hill, Earl of Hillsborough

was sold at Sotheby's, London. The purchaser, who wished to remain anonymous,

agreed to lend the painting to the Ulster Museum for an indefinite period.

IN

JULY, 1975, a large and impressive portrait of Wills Hill, Earl of Hillsborough

was sold at Sotheby's, London. The purchaser, who wished to remain anonymous,

agreed to lend the painting to the Ulster Museum for an indefinite period.

The portrait, which had formerly been in the collection of the Downshire family, is a fine example of the work of the Italian artist Pompeo Batoni (1708-1787) a painter of allegories and classical history pieces who also specialized in painting the English colony in Rome. It seems to have been very fashionable to be painted by Batoni, while making the grand tour of Europe. The fact that several of his sitters are shown wearing uniform, and in one instance, full Highland dress, costume which would not normally have been carried en route, suggests that many of his English patrons went to Rome with the express intention of being painted by him.

Batoni's portraits of Grand Tourists and Englishmen abroad follow a set pattern. The sitter, either in contemporary dress or uniform, is surrounded by objects of classical antiquity, like marble busts, antique vases and broken columns. Recognisable Roman objects, such as the Colosseum or the Temple of Vestra are often shown in the background. The portrait of Wills Hill is very much in this tradition. The Earl leans against an ornate sacrificial altar, gazing fondly at a portrait of his dead wife, Margaretta Fitzgerald, Countess of Hillsborough, who had died in Naples on 25th January, 1765. The artist's signature and the date 1766 are painted on the base of the altar.

The painting is not only a portrait of the Earl and Countess of Hillsborough, but a touching tribute of love from Wills Hill to his dead wife. The torch which is held by the winged figure of Cupid, is a symbol of life. The fact that it still bums strongly, even though it is turned downward, means that the fires of love am still burning, although the loved one is dead. The dog at the Earl's feet is a symbol of fidelity to his wife's memory.

The portrait seems to be saying that Wills Hill had become reconciled to his wife's death. The sarcophagus on which her portrait rests is inscribed

'insano juvat indulgere dolori,

njux,

non haec sine numine Divum

Eveniunt'.

The full text of these lines from Virgil's Aeneid, Book II, lines 776-778, is

'Quid tantum insano juvat indulgere dolori,

O dulcis conjux? Non haec sine numine divum

Eveniunt'.

meaning 'Sweet husband, what avails it to indulge this insane grief? These things do not occur without Divine consent'. Aeneas, the central character in the Aeneid, while watching for his lost wife, Creusa, finds only her ghost, who speaks these lines to him and tells him not to weep for her, but go and rebuild his life. Although the painting is a mourning portrait, it is full of hope for the future.

Wills Hill was born at Fair ford, Gloucestershire in 1718, the second and only surviving son of Trevor Hill, 1st Viscount Hillsborough. In May, 1742, he entered parliament, representing the boroughs of Warwick and Huntingdon, and succeeded his father in the peerage of Ireland in May, 1742. In July, 1742, he was appointed Lord-Lieutenant of Co. Down, and, in November, 1743, took his seat for the first time in the Irish House of Lords. He was created Viscount Kilwarlin and Earl of Hillsborough in 1751.

Throughout his long career in Government, his positions included being Comptroller of the Household to George II, Treasurer of the Chamber, joint Postmaster-General, Secretary of State for the Northern Department, in the peerage of Great Britain, in 1772 and Marquis of Downshire in 1789.

Wills Hill seems to have been a man of mixed talents. He showed a stubborn and destructive obstinacy to any concessions to the American colonies, at a time when the relationship between Britain and her American colonies was fraught with difficulties. He has been described as tactless and lacking in foresight, while George III said of him that he did 'not know a man of less judgement than Lord Hillsborough'. On the other hand, he was one of the foremost improving landlords of his time and was greatly loved by those in his home of Hillsborough. It is largely due to him that the town of Hillsborough stands as it does today. He planned a large part of the town, restored the Fort, which had fallen into decay, and built Hillsborough Castle, formerly Government House. Between 1760 and 1773, he restored and enlarged St. Malachy's Parish Church, one of the most attractive 18th century churches in Ireland, and was greatly involved in all stages of its erection. He was widely known as a patron of the arts and sponsored the publication of Oliver Goldsmith's "The Deserted Village".

Wills Hill married Margaretta Fitzgerald in 1748 and had five children. His second marriage, to Mary, Baroness Stawell in 1768, was childless. He died on 7th October, 1793 and was buried at Hillsborough.

Sources:

- John Steegman, 'Some English Portraits by Pompeo Batoni', Burlington Magazine, 516, vol. LXXXVIII, March, 1946.

- John Barry, 'Hillsborough', (Belfast. 1962).

- Dictionary of National Biography.

- Ulster Architectural Heritage Society, 'Mid Down'.

JOHN WESLEY AND EARLY METHODISM IN LISBURN

By E. J. BEST

FOR ONE who declared the world to be his parish, the Rev. John Wesley visited Lisburn remarkably often, in fact at least fourteen times. He was an extraordinary man, interested in people, medicine, history, poetry and philosophy, which he would read whilst riding his horse from one place to another, because he hated to waste time. In 1770 he calculated he had ridden "above a hundred thousand miles", and he still had twenty years travelling to do, although when he was over seventy he used a coach.

He habitually rose at four for meditation, before setting out on his travels, travelling four thousand miles, sometimes five thousand a year: preached rarely less than twice a day, often four or five times, presided over the affairs of his circuits, and wrote constantly, articles, letters and observations, as well as running surgeries for the poor.

After his conversion in May, 1736, he wrote, "Leisure and I have taken years of one another I propose to be busy as long as I live, if my health is so long indulged me". It was indulged him until March, 1791, when at the age of eighty seven, he died.

He was a natural leader, single minded, autocratic, somewhat detached from his fellows, with a mind like a calculating machine. He would never allow personal relationships to interfere with his mission of evangelism, although when approached he enjoyed conversation.

The Rev. George Whitefield was the first Methodist preacher to visit Lisburn. He was the son of the keeper of the Bell Inn at Gloucester, and as his father died when he was two, his mother brought him up to help and do menial tasks at the Inn. Later in 1732, when he enrolled in Pembroke College, Oxford, he paid his way by waiting on the "gentlemen" undergraduates. This; is where he first met John Wesley, when he joined the `Holy Club'. He was ordained deacon in 1736. He brought something of the Bar room manner to religion. His answer to the problem of a small boy who refused to say the Lords Prayer was to deal him several blows. He had a squint which led his listeners to feel they could not escape his gaze, and preached dramatically in a melodious voice. He too was an indefatigable traveller, crossing the Atlantic thirteen times. As he embraced Calvanism, a doctrine of predestination of man to salvation or damnation, the harsher features of which have been softened by time, he came to a point of disagreement with John Wesley, who favoured Arminianism, which held that salvation was open to all believers and penitents.

Because Whitefield emphasised preaching, and was unconcerned with organisation, it came about that English and Irish Methodism would become entirely Arminian in its theology.

The itinerant preachers must have been a novelty when they first appeared, and they filled a gap in many "peoples" lives: but it is mostly due to a few dedicated people that Methodism first flourished in Lisburn and its surrounding country. The Rev. John Wesley first came to it in 1756, and made a strong impression on Mr. and Mrs. Hans Cumberland, who invited him to stay in their small house in Bow Street, which was also a bakery. At first John Wesley was pessimistic about the success of the society in Lisburn as there were so many different sorts already, but thanks mainly to the liking and respect of the townsfolk for Mrs. Cumberland no strong opposition arose. Whilst he was lodging with the Cumberlands, Mr. Wesley was visited by the Rector of Lisburn and his curate, enjoying their friendly conversation for two hours. Years later in 1785 he was invited to preach in the Presbyterian Meeting House to a large congregation.

Mr. and Mrs. Cumberland's son Frank also made a contribution to the beginnings of Methodism in Lisburn. He was a clerk at Derriaghy Church, but when the clergy and vestry heard he was a Methodist, he was dismissed from his post, consequently going to live in England for two years, where he retained his contact with the Methodists, coming home to Lisburn in 1768 "full of fire and zeal".

If Lisburn has a ghost flitting down Bow Street it would be fortunate if it were Mrs. Cumberland. She was a kindly consistently good woman, respected and loved, She was a friend to the wealthy patronesses, such as Mrs. Gayer and her daughter, and welcomed the less fortunate to her house with equal warmth. She lived until 1787, when in the last two years of her life she endured much pain with great patience.

One person who never forgot her first meeting with Mr. Wesley was a blind girl, Margaret Davidson, from Comber, who came to live in Lisburn, eventually becoming a preacher. She described the event . . . "I was placed near him and could just observe the waving of his hand between me and the light. After preaching he took me gently by the hand and said, "Faint not, go on, and you shall see in glory".

Mrs. Gayer was the daughter of Valentine Jones, Esq., and

Mrs, Jones, a lively Huguenot lady. She inherited her parents chum and was

highly accomplished. In 1758 she married Edward Gayer, and went to live in a

pleasant house at Derriaghy. As she grew older her thoughts took a more serious

turn. It is told that on one occasion when she went to a Ball, she took her

prayer book with her and after each dance retired and read a portion of it . ..

She met Mr. Crommelyn, a great nephew of the celebrated Louis Crommelyn, who was

a surgeon of a regiment of dragoons stationed in Lisburn and a hearty Methodist.

Not long afterwards she called on Mrs. Cumberland who invited her to a meeting,

and it may have been influential coincidence that persuaded her to become a

Methodist.

![]()

In 1773 she had the opportunity of hearing Mr. Wesley preach, and on meeting after the service he said he would call on her. The following day Mr. Wesley walked out to Derriaghy and met Mr. Gayer in the Avenue leading to his house. They entered into conversation and Mr. Gayer, impressed by the culture and gentlemanly deportment of the stranger, invited him to dinner. Arrangements were later made for regular preaching at Derriaghy, and not only was a room set apart for the preacher in his house (called the Prophets Chamber) but Mr. Wesley was kindly and hospitably entertained at regular intervals for many years.

"The old Wesleyan Methodist Chapel was associated with the celebrated preachers who exercised great influence over the congregation in Lisburn. A new sect founded by John Wesley had made considerable progress in all parts of Ireland, and large numbers of people collected from the highways and byways were found in its ranks. As it had been in early times of the Christian world, there arose to take part in ministerial duties of the religious fraternity many men who had never passed through any collegiate course, nor ever received what might be considered a fairly finished education at any of the schools of the day. And yet these followers of the founder of their creed seemed to have been specially adopted for addressing with effect the multitude that thronged the temporary tabernacles in which they preached".

On John Wesley's last visit to Lisburn in 1789, he preached in the original Chapel, which he called the new Chapel. It had been enlarged and redecorated and was described by him as the largest and best furnished Preaching House in the north of Ireland. The Rev. John Wesley often referred to his churches as Houses.

This however was all very well, but at the beginning the itinerant preachers could hurry off to their next assignment, leaving the local people to carry the burden of displeasure, ridicule, and sometimes violence.

At one time there was disagreement within the ranks, and a second church was built facing the older one, called the Methodist Refuge Chapel.

The Methodists used to rise at five o'clock for prayers. Sunday worship was followed by a sermon every Thursday, a prayer meeting every evening of the week except Saturday, (and in John Wesley's original Hymn Rook, printed in 1777, there was a section for hymns for use on Saturday to prepare for the Sabbath).

III

The practice of having prayer meetings in each others houses was commonplace, especially in country districts where Methodism took a strong hold. In Crookshank's history of Methodism in Ireland he says . . . "On the Lisburn Circuit the preachers persevered in their arduous and self denying work. Frequently during the winter for want of room they had to preach out of doors, sometimes standing in the snow". Miss Anne Lutton in her diary remembers a preacher arriving in Moira one Sunday morning. . . "The younger members of the household were gazing idly out of the window, when a stranger rode up to the principal Inn, dismounted, gave his horse to the usual attendant, unstrapped a huge pair of saddle bags and flinging them over his arm strode into the Inn. He was not like any they had seen before, plain but not in Quaker costume . .. so they ran to report the matter to their father. He immediately observed that it was most probably a Methodist preacher, and as he believed these men were generally poor, and the stranger might not order a dinner at the Inn, he thought he should ask him to come and share theirs . . . In half an hour the family sat around the dinner table with Mr. John Grace, the Methodist preacher.

Travelling for the itinerant preachers held many pitfalls, one of which Mr. Wesley himself encountered. On April 29th,1762, Mr. Wesley arrived at Monaghan and was nearly arrested as a person of questionable design, following an episode of the Whiteboys a few days previously. Mr. Wesley and his two itinerants had scarcely dismounted when some busy folk informed the provost that three strange men had come to the Kings Arms. Mr. Wesley was closely questioned as to his doings and intentions, and would have suffered at least serious inconvenience from the Officials but for two letters, one from the Bishop of Derry, and one from the Earl of Moira, which he had in his pocket. Upon reading these the Provost apologised and wished Mr. Wesley a prosperous journey.

In spite of a busy life Mr. Wesley enjoyed a prolific correspondence. His correspondence with women was the relationship with them that he seemed most to enjoy. His letters were full of thought provoking phrases, such as . . . "I have been afraid lest you should exchange the simplicity, of the gospel for a philosophical religion."

Wesley's teaching in a nutshell was that Christianity

should aim for the highest standard .. . that being perfect love. He doubted the

effectiveness of trying to frighten people with the prospect of Hell. For him,

Christianity was the way to heaven.

![]()

REFERENCES

- 1. The Dissentors. Michael Watts.

- 2. Reflections of Hugh McCall. Records of Old Lisburn.

- 3. Memorials of a Consecrated Life. Anne Lutton.

- 4. Crookshank's History of Irish Methodism.

- 5: What Methodists Believe. Rupert Davies.

MISCELLANEA FROM NEWSPAPERS

RELATIVE TO LISBURN AND DISTRICT

Four examples are given which illustrate that some things over time have not changed. The description of assault in The Lisburn Weekly Mail would certainly not be reported in this way today and yet such events still happen but today's attitudes would give such an incident no more than a passing glance. The Drumadoney and Parish of Drumaragh referred to in the third extract are Dromara and the townland of Drumadoney in that Parish which lies between Dromara and Dromore.

The value of early newspapers is considerable in building a picture of the past.

The following items am taken from The Belfast News-Letter and General Advertiser, March 6th,1738.

Yesterday, one Samuel Burgas of Lisburn jun. was committed to the Goal of Carrickfergus, by Edward Smith, Esq., for Bigamy.

Lost between Belfast and Lisburn on Saturday the 3d Instant, a large Locket Sleeve Button in Gold, whoever has or may find it, upon their delivering it to the Printer hereof, shall receive half a Guinea Reward (that being very near the real Value) and if it should be offered to be sold, it is hoped all Goldsmiths, etc. will be so kind as to stop it, and they shall have the same Reward.

Stolen or straid, out of a Stable belonging to Samuel Hamilton of Drummadorony, in the Parish of Drumaragh, in the County of Down, in the Night-time, between the eleventh and twelfth of this Instant February, a black Horse, without any white Marks, wide ear�d, a Bite of a horse on his far Ear not yet whole, hath an open in the Hoofe of the far hind Foot, near to the Hair: Whoever gives Notice to the said Samuel Hamilton of the said Horse, so as he may get him, and discovers the Thief, so as he be convicted, shall have Half a Guinea Reward paid him by the said Samuel Hamilton, or by the Printer hereof.

The Lisburn Weekly Mail

Saturday lst July, 1905

DREADFUL ASSAULT ON A WOMAN

Last night about ten o'clock in Bridge Street was witnessed

a most brutal and savage attack on a woman. The perpetrator, by appearance,

seemed to be under the influence of drink. The pair were seen to emerge from a

public house, and apparently without any provocation the man knocked his spouse

hors de combat. A crowd soon gathered, and a young man in trying to make peace

was literally pitched across the street by the now enraged assailant. His next

move was in requesting his better half to get up, which she was unable to do,

but he assisted her up by the hair of her head. She now being unable to stand,

being evidently in a semi-conscious condition, he pitched her with great force

against the pavement. He then started with his feet, and in the most brutal

fashion kicked her about the face and body. By this, time a messenger had

succeeded in fetching the police, and on their approaching the woman was brought

into a house closeby, and the perpetrator stood calmly on the kerb and all was

at an end.

![]()