- Front Page

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- The Celebration Of Nuptials

- Terminal Diseases In The Parish Of Derriaghy

- Drumbeg 1800-1860

- The Lisburn Workhouse During The Famine

- George Rawdon's Lisburn

- The Lisburn Area In The Early Christian Period Part 2: Some People And Places

- Bygone Days

- Aghalee Local History Study Group

- Wallace Fountain

- Lisburn Courthouse

- Historical Journals

DRUMBEG 1800-1860

Eileen Black

Drumbeg during the first sixty years of the nineteenth century was in a state of change, as owners of the three large estates around Drumbridge-Ballydrain, Wilmont and Drum-came and went. In this period, the houses at Ballydrain and Wilmont were knocked down and rebuilt in the style (with some modifications) in which we know them today: Ballydrain in 1837-8, Wilmont in 1859. Both estates have been dealt with by the author in previous volumes of this journal.1 At the time of writing the Ballydrain article, however, the architect of the rebuilt house was unknown to the author. Further reading has since revealed that the building was in fact designed by Edward Blore (1787-1879), an English architect whose reputation for cheapness brought him a government contract in 1832 to complete Buckingham Palace, after John Nash, the original architect, had been dismissed for extravagance.2 Blore also carried out other work in Ulster: in 1836-7 he enlarged Castle Upton, at Templepatrick, for the 1st Lord Templemore and in 1838-41 designed Crom Castle, Co. Fermanagh for the 3rd Earl of Erne.

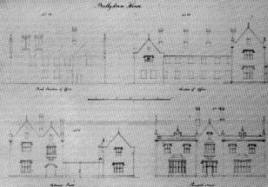

Blore specialized in the Tudor and Elizabethan styles and used them to effect in his numerous country houses, of which Ballydrain is Tudor Revival. In October 1836 he visited the estate `to examine the House and advise with Mr. Montgomery [the new owner] as to the expediency of building on the site of the old House or to change the site. 3 (In the event, the new house was not erected on the original spot but some distance northeast of it). In January of the following year he spent a further two days at Ballydrain and submitted a complete set of plans, elevations, sections and working details, for a fee of £180. A drawing of the elevations is in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (fig. 1) and is doubly interesting when compared with a photograph of the entrance front of the house, taken during the 1860s (fig.2).In February and October 1838 Blore again visited the estate, probably to supervise on-going building. Four years later he undertook further work for Montgomery, when he designed a gate lodge, gates and a chimney piece for the dining room.4 The house, robust but with an unimposing entrance front, was considerably improved by W. H. Lynn's alterations of 1876, which created the building as it is today, with the exception of a few changes carried out by the current owner, Malone Golf Club.5

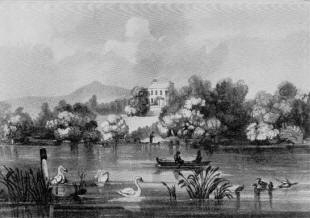

Across Ballydrain lake, in marked contrast to Hugh Montgomery's Tudor edifice, stood Lakefield (fig.3), a plain Georgian-style house, owned by Thomas Alexander Stewart (of the Ballydrain Stewarts) in 1819 and by a Catherine Richardson twenty years later. Lakefield remains something of an enigma: that it was gone by 1858 seems certain, as it no longer appears on the Ordnance Survey map of that year. It was still in existence in 1843, as evidenced by the Guide Through Ireland (p.601), which described this pocket of the Lagan valley in glowing terms:

The old road from Lisburn to Belfast, or as it is usually termed the Malone road ... branches off the mail-coach line at the village of Lambeg, and keeps generally along the left bank of the Lagan ... By this line we pass through a fertile, improved, romantic country, in which are many of the older villas around Belfast, with several bleach-greens and factories, etc. Among the villas we may notice in the vicinity of Lambeg, Lambeg House, Chrome House [Chrome Hill], Drum House and Wilmount [sic]; and to the right of the romantic hamlet of Malone ... are Ballydrane [sic], Lakefield, Lisnoyne, Malone House, etc ...

Although some of these houses have now gone, most remain; the area still has an 'improved, romantic' appearance and remnants of its nineteenth century picturesqueness, despite Belfast's encroachment.

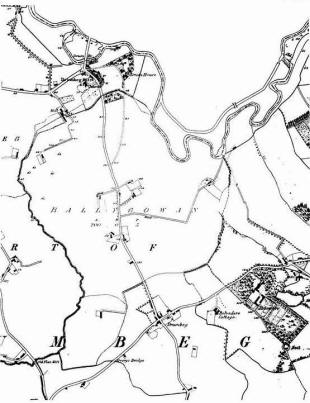

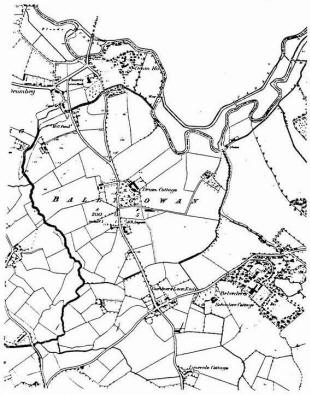

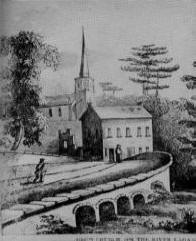

In addition to the changes to the various family seats near Drumbridge, there was another, perhaps more important, alteration to the local landscape: the opening of a new road and the closing of an old one. Until 1837 the road across Drum bridge swung sharply left before it reached Drum church, after which it wound along the side of the church grounds, past Drum House demesne. It then continued through Ballygowan townland to Gardner's Lane, or Loan, Ends at Ballyaughlis (where the Homestead Inn stands). This erstwhile route is clearly visible on the 1834 Ordnance Survey map (fig.4). A more graphic depiction of it, showing its curve to the left, can be seen in an illustration which appeared in the supplement to the Dublin Penny Journal of I835-6 (fig.5). The road's remains, with its arched bridge over the stream from the mill (the latter is shown on fig. 4), can still be seen in the field beside the old graveyard.

|

| Fig. 5. Drum bridge, showing the curve of the old road. (Illustration from the supplement to the Dublin Penny Journal, vol. 4, July 1835-June 1836). |

The proposal to establish the new road, which by-passed Drum House and the church, (shown on

fig.6), was first placed before the Grand

Jury6 (a form of parliament of county gentlemen who acted as a highway authority and received applications - presentments - to undertake new work or repairs) at the Summer Assizes of

1836.7 William Hamilton Smyth, owner of Drum House at that tune (fig. 7) and a member of the Grand Jury of Co. Down, appears to have initiated the road, as records show that he was to be financially responsible for its

upkeep.8 (Most presentment roads were built by landowners, clergy or tenants with large holdings). Though the reason for the road's formation is uncertain, it is possible that Smyth proposed it because of

a growing volume of traffic on the old route, so close to his demesne. This latter road-officially the Belfast to Ballynahinch route-had become increasingly important as a major trunk line out of town by the mid 18308. In

the absentee of a concrete explanation for the re-routing of the road. an increasing flow of traffic close to Drum

House may perhaps have been the cause. The old road, though still marked on the 1860 map, was officially closed in

18459

Besides being picturesque, the land around Drumbeg was highly fertile, with wheat grown extensively and also corn and potatoes. Farms were generally small, on average between fifteen and thirty Irish acres, with sheep and cattle kept on a small scale; large flocks were normally to be seen only on gentlemen's demesnes.10

In an attempt to raise agricultural standards in the district, a number of leading farmers established the Drumbo and Drumbeg Farming Society in

I818, which awarded prizes for farm management, draining and cattle breeding. The society's first ploughing match, held on John Cunningham's fields on 27 February of the following year,

11 attracted twenty-three ploughs and large crowds of spectators. After the judging, some forty to fifty persons, mostly members of the society, repaired to James Gardner's inn at Drum bridge for supper. Among the numerous toasts drunk were 'Our noble patron, the Marquis of Downshire,' 'Miss Maxwell, the Lady of the Soil' (Letitia Maxwell, then owner of Drum estate) and 'Our President, Andrew Durham

Esq.' (of Belvidere). The closing toast struck a universal note: 'God speed the Plough, and success to the Farming Societies of Ireland.'

![]()

The society thrived for many years; in 1843 it had one hundred and thirty-two members, mostly 'practical farmers and resident gentry'.12 Its efforts to raise the standard of ploughing in the district were evidently (and finally) successful, judging from a report of a ploughing of Drumbeg glebe lands in 1847 by the parish inhabitants, as a token of regard for the rector: 'In one of the fields ... there were several places of ploughing executed in a creditable mariner. The improvement, during the last few years, in this department, is strikingly apparent. Formerly, there was a difficulty in procuring a competent workman in this business; but now, owing to our Farming Society, it is rare to find a bad hand.'13

The prosperity of the district and the industrious habits of its population were considered noteworthy in a number of contemporary accounts of the area14 including Philip Dixon Hardy's Northern Tourist of 1830:

The private roads in Upper and Lower Malone, in the neighbouring parish of Drumbeg, and in a great part of Derriaghy, are inhabited by a race of people [descendants of Scots and English settlers], denoting in the appearance of their habitations, and in their names, a different origin from that of their neighbours of the high road. They inherit a marked disposition for cleanliness and comfort, which forms one of the best and most distinguishable characteristics in a peasantry ... (pp.203-4).

Housing conditions were also good. According to the

Ordnance Survey Memoirs of 1837, about a quarter of the houses in Drumbeg parish were slated and about one seventh two-storied. 'The Majority of the Farm houses [the Memoirs record] are whitewashed with lime outside, well lit with handsome sash windows ... and the interiors in every respect neat and comfortable, and almost all furnished with handsome clocks, the farm yards

tollerably [sic] large, well enclosed ... The cottiers' houses too are with very few exceptions, whitewashed outside and inside, well lit with small glass windows and in other respects

tollerably [sic] comfortable.' Emigration from the area was almost negligible, there being sufficient work for all in the local bleach greens, flour and

corn mills.

The population of the area was generally law-abiding. The Ordnance Survey Memoirs record that there was no smuggling or illicit distillation in the parish nor any Orange or Ribbon (nationalist) lodges to be round. Crime in the district appears to have been rare and elicited widespread condemnation whenever it occurred. In October 1811 a turf stack belonging to James Cunningham of Drumbridge was maliciously set alight, 'the first instance of such an atrocious crime having been committed in the neighbourhood ...' In an effort to catch the culprit (s), a number of local inhabitants raised £65 19s 6d as a reward.15 Generally, however, good neighbourliness seems to have prevailed. In February 1819 Alexander Williamson, a linen merchant and bleacher of Lambeg House, thanked, via the News-Letter, the residents of the district between Drumbridge and Lambeg, who helped save linens worth £600, swept off his bleach green by a flood. 16 His gratitude was heartfelt: 'The circumstance reflects credit to the inhabitants of this neighbourhood, and is a greater significance to his mind than the saving of his property. He has the pleasure of informing them, that out of 216 Pieces of fine Linens, carried away that night, he has, by their exertions and assistance, received them all but Six Pieces.'

There appears to have been little amusement for the youth of the area, apart from bullet matches (road bowls).17 For those with literary inclinations, the Dunmurry Reading Society, established in 1823, was highly popular. The society, one of the most prosperous in the parish, met regularly in Dunmurry School House and had a membership of over eighty in 1837, from all classes and creeds. Their library, at that time, was extremely well-stocked, with over seven hundred volumes.18

The opening of the Ulster Railway line between Belfast and Lisburn in August 1839 undoubtedly had a' considerable impact on the district-and on

Drumbeg-especially as an intermediate stop was provided at Dunmurry.19

Belfast and Lisburn, hitherto a sluggish journey by horsedrawn vehicle, became

immediately more accessible. By the mid 1850s, passenger demand had grown by almost fifty percent, with ten trains making the trip daily. Given this shortening of journeys, it is perhaps not surprising that the owners of Ballydrain and

Wilmont, Hugh Montgomery and James Bristow, were business men with commercial lives centred upon

Belfast; both were Directors of the Northern Bank and Presidents of the Chamber of Commerce. Drumbeg as

surburbia, it might be said, had its beginnings in these years of change.

![]()

References

| 1. | See the following: 'Wilmont, Dunmurry: a profile', Lisburn Historical Society Journal, vo1. 4, December 1982; 'Ballydrain, Dunmurry -an estate through the ages,' ibid., vol5, December 1984; 'Mr. Stewart's ballroom near Lisburn: further reflection. on Ballydrain,' ibid., vol 6, Winter 1986-1987. |

| 2. | The attribution to Blare was kindly drawn to my attention by Hugh Dixon. See Howard Colvin, A Biographical Dictionary of British Architects 1600 - 1840, 1978, revised ed. |

| 3. | Blore's Account Book, Add. MS 3956, folio 40, University Library, Cambridge, contains details of his visits to Ballydrain and the work undertaken there. |

| 4. | A drawing of the chimney piece is in the V and A., ref. no. 8752.1, A268. |

| 5. | Photographs of the entrance front after the 1876 alterations and of the house as it is at present, arc illustrated in the Ballydrain article, vol. 5, referred to in note 1 above. |

| 6. | For information on the roads of Co. Down and on the Grand Jury, see LT. Fulton, 'The roads of Co. Down, 1600- 1900: The Evolution of the Road System of an Irish County' (unpublished Ph.D. thesis, Queen's University, Belfast, 1972). I am grateful to Christine Kinealy for drawing this to my attention. |

| 7. | Down Warrants 1833-1836. PRONI. Dow 4/2/12A, p.194. |

| 8. | Ibid., 1837-1838, PRONI, DOW 4/2/13A, p.52. |

| 9. | lbid., 1845-1846, PROM, DOW 4/2/17. |

| 10. | E. R. R. Green, The Lagan Valley 1800-1850, 1949. |

| 11. | Belfast News-Letter, l2 March 1819. |

| 12. | Northern Whig, I I February 1843 |

| 13. | Ibid., 21 December 1847. |

| 14. | See the following: John Gough, Tour in Ireland in 1813 and 1814 (rd.); Thomas Reid, Travels in Ireland at the year 1822, 1823; H. D. Inglis, A Journey through Ireland, 1834. |

| 15. | Belfast News -Letter, 29 October 1811. |

| 16. | Ibid., 5 February 1819. |

| 17. | Road bowls or 'bullets' is a game played with a 28 oz. it., bowl over a distance of approximately three miles of country road, the winner being the bowler who covers the distance with the least number of throws. In the nineteenth century bullets were played around Lisburn, Ballynahinch and Saintfield; also around Ballylesson and Ballyaughlis (Gardner's Lane Ends). |

| 18. | Ordnance Survey Memoirs. |

| 19. | E.M. Patterson, The Great Northern Railway of Ireland, 1962. |

Eileen Black is an Assistant Keeper in the Ulster Museum's Art Department, with curatorial responsibility for

the pre-twentieth century oil painting collection. She has published articles on art and on local historical

subjects in numerous journals and was responsible for editing the Museum's major exhibition catalogue,

Kings in Conflict: Ireland in the 1690s, published in 1990.

![]()