- Front Page

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- The Celebration Of Nuptials

- Terminal Diseases In The Parish Of Derriaghy

- Drumbeg 1800-1860

- The Lisburn Workhouse During The Famine

- George Rawdon's Lisburn

- The Lisburn Area In The Early Christian Period Part 2: Some People And Places

- Bygone Days

- Aghalee Local History Study Group

- Wallace Fountain

- Lisburn Courthouse

- Historical Journals

THE LISBURN WORKHOUSE DURING THE FAMINE

Dr. Christine Kinealy

|

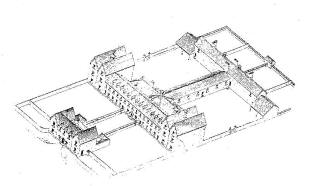

| Fig. 1. Bird's eye view of Lisburn workhouse, designed by George Wilkinson. |

Nineteenth century Ireland was a highly regionalised country about which it is difficult to make generalisations. This diversity is apparent in the administration of the Poor Law between 1838 and 1948 which, although intended to be a uniform system throughout the country, in fact varied from Poor Law Union to

Poor Law Union. During the Famine years of 1845-51, when the Poor Law was an important agency for providing relief, this regional diversity was even more marked. This was mainly because the causes and the impact of distress varied over time and geographic area. At the same time, the response to the distress in the local unions depended both on the interest of the individual Board of Guardians and upon the financial resources which they had at their disposal at any particular period. As a result of this, it is not surprising that during the Famine the regional discrepancies in levels of distress and provision of relief were significant.

The impact of the Famine in the province of Ulster has sometimes been over-shadowed by the distress which occurred in the west of the country. Even within Ulster, however, there were considerable differences in the impact of the distress

on the various Poor Law Unions. This ranged from the officially declared 'distressed' Union of Glenties in Co. Donegal which was-albeit reluctantly-financed by the government, to the highly regarded 'model' unions of Belfast and Newtownards which, throughout the Famine years, were able to remain self-financing. The following examination of the role of the Lisburn Workhouse during the Famine is intended to show how one Ulster Board of Guardians responded to these years of distress and to what extent their reactions were determined by particular local, economic and social conditions.

The 1838 Poor Law Act divided the country into 130 new administrative units known as Poor Law Unions. Each union had its own workhouse which was usually situated in or near a market town and which was administered by a Board of Guardians. Each Poor Law Union was to be financially self-supporting, the workhouse being maintained by poor rates which were raised locally. The size of the Poor Law Unions varied considerably, the largest ones being in the west of Ireland and the smallest ones i n the eastern part of Ulster, where the population was most

dense.1 The Lisburn Union comprised the town of Lisburn and its twenty-six surrounding townlands. It covered 119, 300 statute acres and in 1841 had a population of 75,444. This compares with the neighbouring unions of Antrim, Belfast, Newtownards, Downpatrick, Banbridge and

Lugan which respectively had populations of 49,168; 100,992; 60,165; 74,938; 87,323, and

71,128.2

Each Poor Law Union was administered by a Board of Guardians, two thirds of whom were elected locally, the remainder being ex-officio Guardians. The elected Guardians were usually successful local business men or large farmers, although the executive of each committee was generally drawn from ex-officio membership. At their first meeting on 20 February 1839, the Lisburn Guardians elected James Watson of Brookhill as Chairman, William Caldbeck as Vice-Chairman and William Graham as deputy Vice-Chairman. The Guardians decided to hold their weekly meetings on Tuesdays, which coincided with local

marketday,3 The practice of meeting on Tuesdays continued until the final meeting of the Lisburn Guardians in September 1948.

The Irish Poor Law made no provision for outdoor relief, relief only being given

to those who became residents of the workhouses.

This meant that the Poor law was inoperative until the workhouses were opened.

One of the first tasks of the newly-elected Guardians therefore was to oversee

the valuation of the union and to superintend the building of the

workhouse. The Lisburn Guardians asked the Marquis of Hertford to provide six

acres of land for use as a site for the workhouse and requested the Marquis of

Downshire to supply free stone from his quarry near Moira for the

building.4 Despite strong local competition, the contract for

erecting it was given to Arthur Williams and Sons of Dublin who submitted the

lowest tender at �6,200, which compared favourably with the estimate of �8,500

proposed by John Linn of Lisburn. The firm of Williams also built the workhouses

in Lurgan and Belfast.5

In keeping with the government's desire to make the Poor Law system uniform the majority of Irish workhouses, including those built by Williams, conformed to a standard design

(fig. 1.) proposed by George Wilkinson, the Poor Law's official architect. Wilkinson's advice that each workhouse was to be 'uniform and cheap, durable and unattractive' strongly emphasised the deterrent aspect of Poor Law relief which strove to ensure that only the really destitute would

apply.6 The building of Lisburn's workhouse on its site on the Hillsborough Road was carried out quickly in accordance with the instructions of the government. It opened on 11 February

1841.7

![]()

The size of the workhouses in Ireland varied to accommodate between 400 and

2.000 paupers, the Lisburn workhouse being built to hold 800 initiates. Within a week of its opening 250 paupers had applied for and been granted workhouse

relief.8 The majority of these people were old, young or infirm, and not the able-bodied males so feared by the administrators of the Poor Law. In January 1845,

on the eve of the potato blight, there were only 341 inmates in the Lisburn workhouse, many of whom were sick. This established a pattern which, with the exception of the Famine years, continued throughout the history of the Poor Law-that is, that in many ways, workhouses took

on the role of community hospitals rather that refuges for large numbers of able-bodied

adults, described by the government as the 'undeserving poor.'

The potato blight, which was the immediate cause of the Famine, was first noticed in Co. Cork in September 1845 although the full extent of the damage it had caused was not realised until general digging took place it October. By this time it was obvious that blight had affected the potato crop primarily in the south and west of the country with only isolated instances appearing in

Ulster.10 Consequently, there was no discernable increase in the demand for relief in Ulster in the latter part of 1845, a pattern which also held true for the Lisburn workhouse. At the end of October 1845, after a visit, the Marquis of Hertford and Captain Henry Marvell RN, MP for the town, commented in the Visitors' Book that they believed Lisburn's

establishment was not excelled by any similar institution in England. The Marquis's approval even extended to providing,

at his own expense a special dinner for the paupers, which consisted of beef, carrots and soup, followed by tea and currant

buns.11

In order to meet the increase in distress which was expected in some parts of the country following the appearance of blight, the government introduced various temporary relief measures. Local relief committees were established which could receive grants for the provision of relief, grain was imported into the country, and the public works were given additional funds in order to provide employment. By providing these additions relief measures, the

government hoped that they would be able to avoid extending the permanent system of Pool Law relief. Due to these policies, the demand for workhouse relief showed little change in the winter of 1845-6. In fact, the main change in the administration of the Poor Law was in regard to workhouse diet. As early as October 1845, the Poor Law Commissioners (the central governing body) informed all Poor Law Guardians it Ireland that they would allow potatoes - a stable part of the workhouse diet - to be replaced by other foodstuffs, such as bread, rice or soup. In the Lisburn Union, the guardians felt this to be unnecessary as they were still able to obtain good quality potatoes at the same price. By January 1846, however, the situation had changed and the local contractor was no longer able to obtain sound potatoes. In consequence, the Guardian: decided that instead of potatoes, the paupers should have soup four days a week, stirabout two days and potatoes only one day a

week.13

In 1846 the potato harvest failed for the second time. In 1845 the impact of the blight had been localised

but in 1846, the crop in every part of the country was affected.14 In the Lisburn Union, the crop failed

totally.15 This had two major consequences: firstly, some of the rate payers, particularly the small farmers, found a

difficult to pay their rates, and secondly, there was an increase in demand for workhouse relief. The Guardian responded to the hardship felt by smaller rate-payers by allowing them an additional two months to settle their accounts. They warned, however, that if rates were not then paid, they would take legal action against

them.16

The increase in the number of workhouse inmates was a more immediate problem as, by November 1846 there were more people in the workhouse than it could accommodate (see fig. 2). This increase in demand to workhouse relief was repeated in practically every Poor Law Union in

the country and was partly due to a change In policy by the government in the second year of distress. The relief measures introduced in 1845 were intended lobe temporary measures only. Following the reappearance of blight, however, the

government determined to force the local landlords to play a larger role in the provision of relief. To facilitate this, public works were now extended throughout the country, although the unprecedented demand for relief meant that they were unable to provide sufficient employment for the distressed population.

One of the consequences of the inability of the public works to provide sufficient relief was that an increasing number of people turned to local workhouses for support. The regional contrasts in this demand to relief are marked; in Co. Antrim, for example, the average number of people employed daily on the public work was 270-the lowest number in the whole of Ireland. This compares with a daily average of 335 in Co. Down 2,329 in Co. Tyrone, 4,065 in Co. Fermanagh and 9,002 in Co. Donegal. Even within Ulster, therefore, there were considerable regional contrasts which were even more marked when compared to the situation in the rest of the country: in Co. Clare, for example, 31,310 were employed daily on the public works, in Co. Galway there were 33,325 and in Co. Cork 42, 134.17 To a large extent, these regional variations reflect the levels of dependence of the local population on the potato as a stable crop. In many parts of Ulster, however, notably in the north eastern part, income derived from weaving provided a safely net against the worst effects of the blight.

In the winter of 1846-7 the demand for admittance to the Lisburn workhouse began to increase. Although there was little sickness in the institution, the Guardians were aware that infectious diseases might break out if overcrowding occurred They therefore responded to the demand by building additional sleeping galleries in the dormitories, to accommodate a further two hundred inmates. This accorded with the recommendations to the Poor Law Commissioners who under no circumstances wanted the Guardians to provide relief to people why were not residents of the workhouse.18 The reaction of the Lisburn Guardians is in sharp contrast to that of Guardians in many other parts of the country, particularly those where the public works were unable to provide sufficient relief. In these areas, many of the Guardians reacted to the second year of distress by introducing an ad hoc system of outdoor relief, even though it was absolutely forbidden under the terms of the Poor Law Act. Although this was most prevalent in the south and west of the country, in Co. Down both the Kilkeel and Banbridge Guardians intermittently provided illicit relief, despite repeated orders from the Poor Law Commissioner to desist.19 In Banbridge in April 1847, for example, the Guardians refused 1,271 persons workhouse relief because of overcrowding and instead gave each applicant food to take home.20

The inability of the government to provide sufficient relief through the public works, which resulted in a growing demand for workhouse relief, made a further change of policy inevitable. The government therefore decided that after August 1847 the Poor Law was to be the main provider of relief. To make this possible, outdoor relief was for the first tune to be officially permitted. Twenty-two unions along the western seaboard were officially declared `distressed' and were to receive external financial assistance, although the other unions were to remain self-supporting as far as possible. To facilitate the change from public works to Poor Law relief, soup kitchens were established throughout Ireland during the summer of 1847, which, as their name suggests, provided relief in the form of soup. At its peak, over three million people in Ireland (almost half the population) availed themselves of this form of relief. Again, the regional variations are marked, the percentage of the population which received daily rations of soup in the Lisburn Union being 3 per cent, in Banbridge 17 per cent and in Larne 20 per cent. By contrast, in the Belfast, Newtownards and Antrim unions, soup kitchens proved to be unnecessary. The daily average in other parts of the country, particularly the west, was much higher than in Ulster. In the Gort Union 86 per cent of the population was in daily receipt of soup, in the Swinford Union the figure was 84 per cent and in the Clifden Union it was 87 per

cent.21

![]()

The transfer to Poor Law relief in August 1847 coincided with a temporary depression in the linen industry which affected the small weavers of Cos. Antrim and Down. This had a short-term but significant impact on the number of people requiring relief in these areas. In the Lisburn union, the distress amongst the weavers made the provision of outdoor relief necessary. It was provided, however, subject to very stringent controls. For example, it was given only to the old or sick and was in the form of cooked food -stirabout - and not in cash. Simultaneously, relief provided within the workhouse was to be subject to tighter control in an effort to deter all but the really destitute from applying. Corn mills were to be erected in the workhouse, in which the able-bodied men were to be employed, whilst the female inmates were to be employed in oakum picking.22

Although blight reappeared in some parts of Ireland in the harvest of 1848, its impact on the Lisburn union was counter-balanced by a revival in the linen industry. As a result, the number of people seeking relief began to decline. The harvest of 1848, in fact, in many ways marked a watershed in the Famine. In the eastern part of Ulster, the worst was over; however, in other parts of the country, particularly along the western seaboard, the effect of a fourth year of distress was devastating. In the Lisburn union, there was an obvious reduction in the number of people seeking Poor Law relief. The return to 'normality' in the workhouse is perhaps indicated by the fact that in November 1848 the Marquis of Downshire, following a visit to the establishment, made a donation of one pound which he directed should be spent on the purchase of catechisms for the education of the pauper scholars. 23 There was, however, a temporary increase in mortality in the union when, in early 1849, a number of cases of asiatic cholera were reported in Lisburn. Similar outbreaks occurred in other parts of Ireland at this time, brought in from Britain through ports such as Londonderry, Dublin and Belfast. This cholera epidemic had a short-term impact on mortality rates throughout Ireland.

The continuation and, in some instances, increase in distress in some parts of Ireland in 1849, resulted in a shift of policy by the government. At the beginning of 1849, they introduced the Rate-in-Aid Act which imposed an additional rate on the more prosperous unions in Ulster and Leinster, which was then to be redistributed to the poorer unions in the west of Ireland.24 The purpose of this was to make poor relief a national rather than a local responsibility. The unions in Ulster primarily liable for this tax held meetings throughout the Province to protest at its introduction. The Lisburn Guardians described it as a tax on `the industrious population of Ulster for the support of the improvident and indigent poor of the south of Ireland' and ordered that placards be posted throughout the union to this effect. Advertisements were also to be placed in the Northern Whig, Belfast Commercial Chronicle and the Belfast News-Letter. They also convened a public meeting of all rate payers, to be held in the corn market in Lisburn on 3 March.15 However, in spite of the widespread unpopularity of the Rate-in-Aid Act amongst the Ulster Guardians it was generally paid although not as promptly as the usual poor rate.26

The potato crop in 1849 was relatively free from blight, which marked the start of a series of good harvests in Ireland. The exception to this was in parts of the west, particularly in a number of unions in Cos. Clare, Kerry and Galway, where the number of people seeking relief continued to grow

.27 In the Lisburn union by June 1850, the number of inmates in the workhouse had returned to its pre-1845 level. In fact, the number of able-bodied men in the workhouse had dropped so drastically that the Guardians were forced to purchase

an ass to work on the institution's farm." By August, the Guardians were sufficiently confident in the prospects of the local potato crop to re-introduce potatoes into the workhouse diet - three lbs a day to be given to all paupers over the age of

nine.29

In 1852 a visitor from Scotland visited some of the Poor Law unions in the north of Ireland and recorded his findings in the

Glasgow Herald. He described the Lisburn workhouse thus: `Tire house is of very tasteful architecture with long avenues and spaces of ground on all sides blooming with vegetation. Nothing could exceed the milk-white cleanliness of the floors, walls, doors and other furniture of the establishment. There are 15 acres of ground attached to it, which are kept in an excellent state of cultivation by the master, without any assistants but the paupers.;30 He also pointed to the fact that despite an increase in poor rates during the Famine and the fact that the union had paid �50,000 in

rate-in-aid to the distressed unions, the Lisburn union now, had �3,500 in the bank." Again, this is in sharp contrast to unions in the west of Ireland, which were only beginning to emerge from the effects of seven consecutive years of distress. The Lisburn Poor Law Union, therefore, had

survived the Famine years with relatively little hardship. Furthermore, due to the relatively buoyant economic

situation, conditions within the union by the early 1850s were able to return to their pre-Famine condition within

a very short space of time.

![]()

References

| 1 | See C. Kinealy, `The Administration of the Irish Poor Law 1838-62,' unpublished Ph.D. thesis (T. C. D., 1984). passim. |

|

2 |

Appendix to Fourth Anneal Report of the Poor Lou Commissioners (hereafter AR), 1838. |

|

3 |

Minute Book of Lisburn Board of Guardians (hereafter M.B., Lisburn) PRONI, BG/19/A, 20 February 1839. |

|

4 |

M.B. Lisburn, 20 February 1839, 14 May 1839. |

|

5 |

Ibid., 28 May 1839. |

|

6 |

Fifth AR, 1839. , |

|

7 |

M.B., Lisburn, 9 February 1841. |

|

8 |

Ibid., 16 February 1841. |

|

9 |

Appendix to Eleventh Annual Report of the Poor Law Commissioners, 1846. |

|

10 |

See E.M. Crawford (ed.), Famine: The Irish Famine, 1989. |

|

11 |

M.B., Lisburn, 21 October 1845. |

|

12 |

M.B., Lisburn, 4 November 1845; appendix to Twelfth Annual Report of the Poor Law Commissioners, 1847. |

|

13 |

M.B., Lisburn, 20 January 1846. |

|

14 |

Appendix to Thirteen AR, 1847. |

|

15 |

MR., Lisburn, 5 September 1846. |

|

16 |

Ibid., 5 September 1846. |

|

17 |

Analysis of Returns of Poor Employment under 9 Vic.c. 1 and 9 & 10 Vic.c. 107 front week ending t0 October 1846 to week ending 26 June 1847, p595, H.C.1852 (169) xviii. |

|

18 |

M.B., Lisburn, 12 September 1846, 30 January 1847. |

|

19 |

Correspondence of Poor Law Commissioners to Home Office, PRO, London, h045 1080, passim. |

|

20 |

M.B., Banbridge Union, PRONI, BG/6/A, 4 January 1847 to 12 April 1847. |

|

21 |

Supplementary Appendix to Seventh Report of the Relief Commissioners, pp.18-21; BPP H.C. 1847-8 (956) XXIX. |

|

22 |

M.B., Lisburn, 14 August 1847. |

|

23 |

M.B., Lisburn, 4 November 1848; Ibid., 27 January 1849. |

|

24 |

12 & 13 VIC.C.24. |

|

25 |

M.B., Lisburn, 24 February 1849. |

|

26 |

C. Kinealy' The lash Poor Law', passim. |

|

27 |

First AR 1848; Second AR 1849; Thud AR 1850. |

|

28 |

Minute Books, Lisburn, 20 July 1850. |

|

29 |

Ibid., 17 August 1850. |

|

30 |

Northern Whig, 10 February 1852. |

|

31 |

Ibid. |

Dr. Kinealy was Administrator of the Ulster Historical Foundation for some years and is now employed by the

Institute of Irish Studies al Liverpool University. Her speciality is the Famine in Ireland, on which she is

publishing a major work in 1991.

| Fig. 2. Admissions and deaths in Lisburn workhouse, 1846-51. | |||

|

Week ending |

No of admissions | Total no in workhouse | Deaths in workhouse |

| 05-Dec 1846 | 53 | 855 | 2 |

| 6 March 1847 | 36 | 909 | 20 |

| 5 June 1847 | 75 | 987 | 18 |

| 04-Sep1847 | 34 | 538 | 7 |

| 04-Dec1847 | 62 | 723 | 6 |

| 4 March 1848 | 28 | 855 | 7 |

| 3 June 1848 | 41 | 692 | 4 |

| 02-Sep1848 | 9 | 504 | 2 |

| 02-Dec1848 | 26 | 641 | 3 |

| 3 March 1849 | 29 | 662 | 9 |

| 2 June 1849 | 12 | 514 | 3 |

| 01-Sep1849 | 8 | 406 | 2 |

| 01-Dec1849 | 36 | 425 | 1 |

| 2 March 1850 | 11 | 449 | - |

| 1 June 1850 | 11 | 373 | 2 |

| 07-Sep1850 | 1 | 276 | 2 |

| 07-Dec1850 | 15 | 334 | 3 |

| 1 March 1850 | 18 | 388 | 2 |

| Figures extracted from Minute Books of Lisburn's Board of Guardians (PRONI, BG19/A). |

|||