- First Steps

- Footprints

- The Native

- The Warrior

- The Gaelic Chieftain

- THE Gardener

- The Quiet Builder

- The Lady

- The Reverend

- The Sinner

- The Dying Methodist

- The Homecoming Earl

- The Soldier - Statesman

- The Hero

- The Farm Labourer

- The Woman Preacher

- The Jew

- The Orange Man

- The Mollycoddled Boy

- When Footprints Fade

- Acknowledgements

- Other Historical Materials

- Video

External links

The Gaelic Chieftain

Hugh O’Neill was a man who was both loved and loathed. He and his followers were a mighty force across Ireland in the sixteenth century and he hated the English who invaded his country. The English gave him the title Earl of Tyrone but it was always difficult for Elizabeth I to understand whether O’Neill was on her side or against her. One of her deputies reported after meeting him, “Ye captain was proud and insolent; he would not leave his castle to see me, nor had I apt reason to visit him as I would. He shall be paid for this before long. I will not remain long in his debt.”

O’Neill would pledge that he and his tenants would submit to English rule, but before long he would break his promise and rebel again.

In 1599 the Queen sent the Earl of Essex for a “parley” with Tyrone. A truce was agreed, but over the next couple of years O’Neill continued the pressure on the English and eventually a large reward was offered for his capture, dead or alive.

In the battles that followed, O’Neill lost his stronghold in Dungannon. He had many other forts including three close to Moira. One was at the tiny village of Lisnagarvagh (now Lisburn), another at Portmore on the shores of Lough Neagh and one at Innisloughlin.

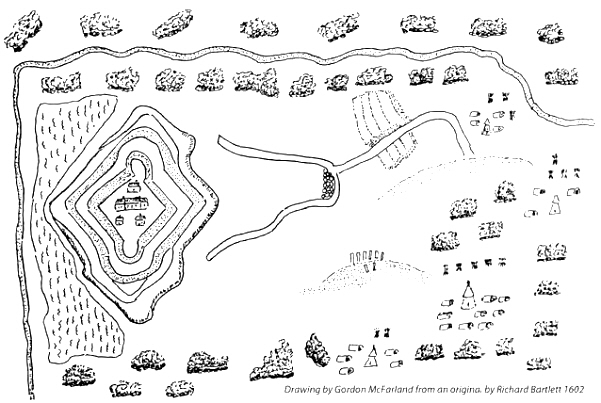

The latter was a stronghold of considerable significance. (The place had many different spellings and was also known as the fort of Killultagh). It was set on higher ground above the Lagan, close to where Spencer’s Bridge is on the Hillsborough Road today. Records from the seventeenth century portray an impressive stronghold. It was “situated in the midst of a great bog and no way accessible, but through thick woods and barely passable.” It consisted of “two deep ditches, both comprised with strong palisades, a very high and broad rampart of earth and timber, and well flanked with bulwarks.”

Sir Arthur Chichester described “Eneslaghane”, as “the chief entrance into the spoil of these parts … a place of great strength and exceeding importance.” Lord Deputy Mountjoy called it “one of the strongest places I have heard of in Ireland.”

O’Neill knew the strategic importance of Innisloughlin and sent his nephew, Brian MacAirt O’Neill, to ensure that the fort was defended. He was given a large number of troops with muskets. It seems O’Neill was so sure of its impregnability that he also deposited much of his treasure there.

The English, under Lord Mountjoy, besieged the fort in the summer of 1602. Despite the fact that it was heavily fortified and almost inaccessible through the trees and the bog, it eventually fell when O’Neill’s army surrendered. Hugh O’Neill’s power was gone. Within a few more years he had left Ireland never to return.

Drawing from an original by Richard Bartlett 1602

Following the fall of Inisloughlin to the English, the fort was granted to Sir Fulke Conway, who repaired and strengthened it. The fort was forty yards square with corner bastions and was surrounded by a moat and parapet. It stood proudly above the Lagan for many years but was levelled in 1803 by the landowner who “filled up its entrenchments, and left only a small fragment of the castle standing.” By 1837 the moat had completely disappeared and only a skeleton of the parapet on the northeast and southeast side survived.

Strongholds become weak; towers tumble and disappear from view; chieftains and conquerors likewise fall and ultimately leave nothing but footprints.

All day long I have held out my hands to an obstinate people, who walk in ways not good, pursuing their own imaginations - a people who continually provoke me to my very face. Isaiah 65:2-3.

“Come now, let us reason together,” says the Lord. “Though your sins

are like scarlet, they shall be as white as snow; though they are red as

crimson, they shall be like wool. If you are willing and obedient, you

will eat the best from the land; but if you resist and rebel, you will

be devoured by the sword. For the mouth of the Lord has spoken.” Isaiah

1:18-20.

The Gardener

Arthur had a dream; he wanted to create something unique in Ireland. Not that he needed something more in his life. He was born in the big house on the hill in Moira, had a very wealthy family and all the benefits of a child of noble birth. He could ride on horseback through the fields and forests that surrounded his home. He loved nature and was fascinated by his father’s passion for growing things. George Rawdon had successfully imported and grafted apple cultivars from England and raised a substantial orchard at his home. As a boy Arthur wandered beneath those trees and dreamed of making a beautiful garden of his own.

Arthur suffered from very poor health. His family were advised to

send him to France where he spent years studying and longing for home.

But home was never to be the same again. In one sad year his two older

brothers and mother died. Eventually he was able to return to Moira to

be with

his ageing father. On the death of his father, he inherited the

Baronetcy and the estate. The young man set about achieving his dream.

Over the next few years, as his garden was taking shape, progress was

interrupted by perilous times in Ireland. In 1685 James II had become

king. Arthur sided with Prince William of Orange and was appointed

Colonel of a regiment of dragoons. Despite his determined leadership at

the “Break

of Dromore,” the Protestant armies were driven further north and

eventually retreated to Londonderry. Rawdon became dangerously sick and

was forced by his friends and physicians to leave the stricken city

before the siege began. He spent quite a while recovering in England and

putting plans in place for his garden.

For several years he had enjoyed a close friendship with Sir Hans Sloane, doctor to royalty and famed for his natural history collection. While Rawdon was convalescing, Sloane returned from an extended trip to Jamaica with wonderful plant specimens and some seeds. He shared some of these seeds with Arthur and enthused him with accounts of the exotic plant life there.

Arthur’s dream intensified. He was determined to try importing not

just seeds but living plants from Jamaica. He had a hot-house built in

Moira. His health prevented him travelling abroad, but in 1689 he

engaged James Harlow to go to Jamaica to bring back as many live plants

as he could. It was

an incredible venture. Would those plants survive an Atlantic crossing?

Would they survive the climate in Ireland?

Arthur returned to Moira in 1690. The Battle of the Boyne was just weeks away. His battle-field career was over though he was still heavily involved in the support of the rebellion. Now called Sir Arthur, he also continued to develop what he hoped would be the greatest garden in the land. Eventually, in April 1692, Harlow arrived with an amazing cargo of one thousand exotic plants and remained in Moira for almost twenty years caring for those plants in the hot-house. Nothing in Europe compared with Arthur’s garden, but he unselfishly shared his plants with gardeners in these islands and beyond. His dream had been realized. Moira demesne became a very special place indeed.

Sadly, Sir Arthur lived only a short time to enjoy the garden he

created and loved, for he died in 1695 at the early age of thirty-four.

Thankfully the gardeners and the family maintained his

wonderful garden for many years and enjoyed showing off the splendour of

their home and demesne. We owe a debt of gratitude to those who visited

the Castle, for without their diaries and journals and illustrations we

would have very little knowledge of Moira demesne’s glorious past.

Rev. John Wesley was a welcome visitor to Moira Castle on his travels through Ireland. He records one visit in May 1760 and tells how he preached “just opposite to the Earl of Moira’s house ..... It stands on a hill with a large avenue in front, bounded by the Church on the opposite hill. The other three sides are covered with orchards, gardens and woods, in which are walks of various kinds.”

Another writer speaks of “a handsome, well-planted and full grown avenue leading to the superb and beautiful seat of the Earl of Moira.”

A later visitor was Gabriel Beranger. He reveals more detail as he

describes the mansion: “a commodious habitation, surrounded by a wood,

which affords beautiful walks, a large lawn extends

in front, where sheep feed, and is terminated by trees, and a small

lough eastwards; the rear of the castle grounds contains a wood, with

large opening fronting the castle, which forms a fine perspective.” He

continued, “On each side of this extensive lawn are shady walks through

the wood, terminated to the east by a long oblong piece of water,

surrounded by gravel walks where one may enjoy the sun in cold weather.

And to the west lies the pleasure and three large kitchen gardens.”

This visit took place when the Sharman family rented the property,

over one hundred years after the garden was begun. The residents still

took a great pride in the place. Beranger went on to describe a “large

abandoned quarry on the west of the demesne which Miss Sharman got

planted and improved and has called it the Pelew. It forms at present a

delightful shrubbery with ups and downs, either by steps or slopes and

has so many turns and windings, that it appears a labyrinth

and contains shady walks and close recesses in which little rural

buildings and seats are judiciously placed, with a little wooden bridge

to pass a small rill of water. Jasmine, woodbine and many flowering

shrubs adorn this charming place.” The quarry was known as McKinley’s

quarry but was filled in during housing development near Oldfort. Some

who have lived in Moira all their lives recall the unusual flowers that

bloomed around it.

The gardener from Moira has been widely recognised as the father of Irish gardening. His dream had become reality, though he never lived to see it mature. Sadly today the dream too has died, leaving only a reasonably attractive and functional park. That is the trouble with gardens; neglect them and they die. George Bernard Shaw describes neglect as the “laziest and commonest of the vices.” But the Bible sounds a much more solemn warning.

How shall we escape if we neglect such a great salvation? Hebrews 2:3. (ESV)

As for man, his days are like grass, he flourishes like a flower of

the field; the wind blows over it and it is gone, and its place

remembers it no more. But from everlasting to everlasting

the Lord’s love is with those who fear him. Psalm 103:15-17.

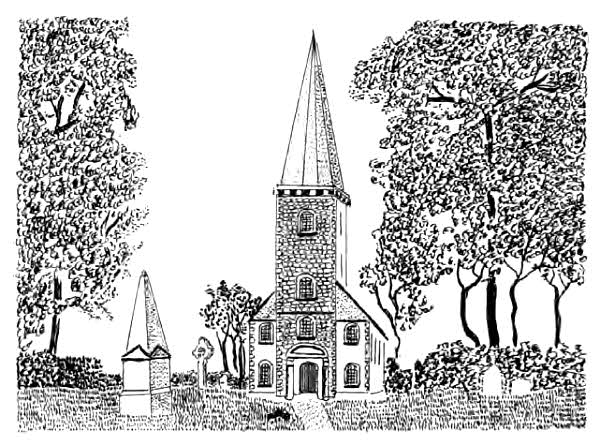

The Quiet Builder

John rose and walked slowly across the expensively furnished bedroom on the first floor of Moira Castle. He coughed heavily at the open window and inhaled the autumn morning air. His tuberculosis was really troubling him today but he wanted to see how his special project was progressing. The sunrise over the Lagan valley silhouetted the new church building on the opposite hill; the sounds of labourers already starting work echoed across to the castle. It was exciting to see the elegant tower with its slate steeple taking shape. He could hardly wait to attend church in his new building. It was the year of 1722.

John was the son of Sir Arthur Rawdon and grandson of Sir George. He was born in 1690, just months before the decisive Battle of the Boyne but all his life he suffered from illness. He never knew his grandfather and he barely remembered his father. Arthur Rawdon had spent every moment either obsessed with military affairs or gardening. Then within a short space of time both his mother and father died. John was just 5 years old.

Despite such a start, John made every effort to lead a fulfilling

life. He eventually followed his grandfather and father into politics

and became a Member of Parliament for County Down

but he always lived in the shadow of their achievements.

The gardens his father created continued to adorn the Castle, though many of the exotic plants had withered and died. John blamed their loss on the carelessness of the servants and the death of Mr. Harlow, the gardener. He demolished the crumbling glass-house his father had built but did all he could to keep the beauty of the demesne. However he had plans of his own; plans that would benefit others in Moira.

Sir John was a well-loved landlord in Moira; everyone spoke highly of

the young man on whom they depended for their livelihood. He was a

person of “great integrity, religion and charity.” The village of Moira

grew as more people came to live there. Many of them were linen dealers.

Sir John also owned the town of Ballynahinch which had been built by his

grandfather. He admired its well developed properties and he determined

that his tenants in Moira would have similarly

improved properties.

He built houses and businesses in local blackstone with narrow

carriage archways leading to quiet court-yards. Some houses were grand

and some suitable for the poorer families. It would

take years of work but Sir John had a vision of what he wanted to leave

for posterity.

But his greatest longing was to see a Church in the village for the

community. Moira was always part of Magheralin Parish but John was

delighted that a decision had been taken to form the Parish of Moira.

Initially services were held in the Charity School but John promised to

help erect a beautiful place of worship. The Hill family from

Hillsborough owned land on the hill opposite the Castle and kindly gave

an acre to the Parish. In return the Hills were given their choice of

burial plot in the grounds.

A later resident of Moira would describe the setting. “Just where the houses terminated, at the lower end of town, were two gates exactly opposite. Each gate opened into a long avenue of tall trees; each avenue led to a noble edifice. One was the Parish Church, the other the Castle of the Earl of Moira; so that from one majestic pile to the other seemed but one continued avenue, with a lovely lawn of green at either end of it.” It was just what John had planned.

John was shaken out of his reverie that morning by a commotion on the

landing. The noise came from his over-excited two-year-old son, also called

John, being chased by a rather frazzled nurse. “It is so good to have a

lively boy,” thought John. Yet he still worried. His first son had died at

the same

age and his third son, who would celebrate his first birthday that very day,

was a sickly child; and his wife was expecting a fourth child next summer.

All of this, on top of his own health problems, made life very difficult.

John often contemplated the future for he knew his life might be short. “What would happen if he died? Would he leave an heir? And what about his people and his village?” He hoped young John would grow up to be a really good landlord and in his will he made sure John would succeed him. He also wanted his tenants to benefit after he was gone. He willed the poor of Moira parish the sum of twelve shillings each. He also made provision for the Church building if it was not completed at the time of his death and left a legacy to continue a school until his son became of age.

As autumn turned to winter, John watched the erection of the church from his window. His health was rapidly deteriorating. Six days a week, the sounds of hammer on stone and wood penetrated the castle windows but on 1st February 1723, John no longer heard them. His fight for life was over and his third son followed him a month later. His second son and heir was just three years old.

It seemed as though the house of Rawdon could be ending. However the

Rawdon name would become famous at home and across the world but none of

them would leave a more lasting footprint upon the village of Moira than

the quiet builder, Sir John Rawdon. John was never able to worship

within the walls of the beautiful St. John’s church but the building was

consecrated later in

the year and has been used for the worship of God ever since. And the

quiet builder still lies in the quiet vault under the place he so

lovingly built.

John’s short life, ending at thirty-three years, so closely mirrored his father’s life. Arthur had died on his thirty-fourth birthday. Both lives were shortened by health problems. But a greater life was violently ended at a similar age.

Jesus Christ said He came “to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many.” Mark 10:45

Jesus of Nazareth … was handed over to you by God’s set purpose and foreknowledge; and you, with the help of wicked men, put him to death by nailing him to the cross. Acts 2:22-23.

This is how we know what love is: Jesus Christ laid down his life for

us. 1 John 3:16.

St. John’s Parish Church